Fertility Transition: the Case of Rural Communities in Karnataka, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maleru (ಮಲ ೇರು माले셁) Mystery Resolved

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 20, Issue 5, Ver. V (May. 2015), PP 06-27 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Scheduling of Tribes: Maleru (ಮಲ ೇರು माले셁) Mystery Resolved V.S.Ramamurthy1 M.D.Narayanamurthy2 and S.Narayan3 1,2,3(No 422, 9th A main, Kalyananagar, Bangalore - 560043, Karnataka, India) Abstract: The scheduling of tribes of Mysore state has been done in 1950 by evolving a list of names of communities from a combination of the 1901 Census list of Animist-Forest and Hill tribes and V.R.Thyagaraja Aiyar's Ethnographic glossary. However, the pooling of communites as Animist-Forest & Hill tribes in the Census had occurred due to the rather artificial classification of castes based on whether they were not the sub- caste of a main caste, their occupation, place of residence and the fictitious religion called ‘Animists’. It is not a true reflection of the so called tribal characteristics such as exclusion of these communities from the mainstrream habitation or rituals. Thus Lambáni, Hasalaru, Koracha, Maleru (Máleru ಮಲ ೇರು माले셁‘sic’ Maaleru) etc have been categorized as forest and hill tribes solely due to the fact that they neither belonged to established castes such as Brahmins, Vokkaligas, Holayas etc nor to the occupation groups such as weavers, potters etc. The scheduling of tribes of Mysore state in the year 1950 was done by en-masse inclusion of some of those communities in the ST list rather than by the study of individual communities. -

Gives Edge to BJP in Karnataka

VERDICT 2019 Sparring between Congress and JD (S) Gives Edge to BJP in Karnataka S. RAJENDRAN A para-motor flying in Vijayapura city on Monday, May 8, 2019, to encourage people to vote in coming Lok Sabha elections. Photo: Rajendra Singh Hajeri. For long a pocket borough of the Congress party Karnataka appears headed for a waveless election. The southern State, which goes to the polls in two phases - 14 seats each on April 18 and April 23, will see a direct contest between the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which is in government in the centre and the Congress-Janata Dal (Secular) combine, which is in power at the State. S. Rajendran, Senior Fellow, The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy, Bengaluru, writes on how each of the main parties to the contest are placed. The two main contestents - the BJP and the Congress-JD (S) coalition, he says, are expected to share the spoils, though the former enjoys an edge. he 2019 General Election to the Lok Sabha for the 28 seats from Karnataka, to be held in two phases on April 18 and 23 (See Appendix for T dates and constituencies1), is expected to be markedly different from the last elections held in 2014. First, this time round the poll will be a direct challenge between the Congress-Janata Dal (Secular) [JD (S)] combine and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Second, there is no perceptible wave in favour of any political party. The two formations are, therefore, expected to share the spoils although the BJP enjoys considerable edge because of two factors: differences within the Congress party and the conflict of interests between the grassroots level workers of the Congress and the JD (S). -

The Salience of Ethnic Categories: Field and Natural Experimental

The Salience of Ethnic Categories: Field and Natural Experimental Evidence from Indian Village Councils Thad Dunning Department of Political Science Yale University This version: April 26, 2009 Prepared for the Faculty Colloquium in Comparative Politics, Princeton University Acknowledgements: I am grateful to Drs. Veena Devi and Ramana, their students and collaborators at Bangalore University, and especially to Dr. B.S. Padmavathi of the international Academy for Creative Teaching (iACT) for assistance with fieldwork. Janhavi Nilekani and Rishabh Khosla of Yale College, with whom I am collaborating on related projects, provided superb research assistance. I also received useful advice or help from Jennifer Bussell, Raúl Madrid, Jim Manor, SS Meenakshisundaram, Nandan Nilekani, Rohini Nilekani, Sunita Parikh, Vijayendra Rao, Sandeep Shastri, Drs. Shaymla and Jeffer of the Karnataka RDPJ, and S.K. Singh of the NIRD in Hyderabad. In-kind support from Kentaro Toyama at Microsoft Research India and financial support from Yale’s Whitney and Betty MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies and the Institution for Social and Policy Studies are gratefully acknowledged. This research was approved by Yale’s Human Subjects Committee under IRB protocol #0812004564. Abstract: Many scholars emphasize that both electoral institutions and the sanctioning of particular ethnic categories by the state may shape the political role of ethnicity, as well as the salience of different forms of ethnic identification. Yet because electoral institutions and state-sanctioned categories may themselves be shaped by patterns of ethnic identification, such causal claims are typically challenging to evaluate empirically. This paper reports results from a field experiment implemented in rural villages in the Indian state of Karnataka, in which the caste relationship between subjects and political candidates in videotaped political speeches was experimentally manipulated. -

Myths and Beliefs on Sacred Groves Among Kembatti Communities: a Case Study from Kodagu District, South-India

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH CULTURE SOCIETY ISSN: 2456-6683 Volume - 1, Issue - 10, Dec – 2017 UGC Approved Monthly, Peer-Reviewed, Refereed, Indexed Journal Impact Factor: 3.449 Publication Date: 31/12/2017 Myths and beliefs on sacred groves among Kembatti communities: A case study from Kodagu District, South-India Goutham A M.1, Annapurna M 2 1Research Scholar, Department of Studies in Anthropology, University of Mysore, Manasagangothri, Mysore, India 2Professor, Department of Studies in Anthropology(Rtd), University of Mysore, Manasagangothri, Mysore, India Email – [email protected] Abstract: Sacred groves are forest patches of pristine vegetation left untouched by the local inhabitants for centuries in the name of deities, related socio-cultural beliefs and taboos. Though the different scientists defined it from various points of view, the central idea or the theme of sacred grove remains the same. Conservation of natural resources through cultural and religious beliefs has been the practice of diverse communities in India, resulting in the occurrence of sacred groves all over the country. Though they are found in all bio-geographical realms of the country, maximum number of sacred groves is reported from Western Ghats, North East India and Central India. In Karnataka, sacred groves are known by many local names such as: Devarakadu, Kaan forest, Siddaravana, Nagabana, Bana etc. This paper gives detailed insight on sacred groves of kodagu District of Karnataka. Indigenous communities like Kembatti Holeyas and Kudiyas defined them as ‘tracts of virgin forest that were left untouched, harbour rich biodiversity, and are protected by the local people due to their cultural and religious beliefs and taboos that the deities reside in them and protect the villagers from different calamities’. -

Linguistic Anthropology, Sociolinguistics and Language Teaching

FACULTY PROFILE 1. Name: Dr. Ravindranath, B. K Photo 2. Designation: Professor 3. Qualification: M.A, (Ling),M.A,(Anthro) PGDS, PGDL, Ph.D., 4. Area of Specialization: Linguistic anthropology, Sociolinguistics and Language teaching. 5. Awarded Junior/Senior Research Fellowship From Anthropological Survey of India, Southern Regional Centre, Mysore and Engaged in the National Project „People of India‟ (1987 – 1990) PUBLICATIONS: 1. Ravindranath, B. K. (2000). Devadiga. In K.S. Singh (Ed.), People of India: Karnataka, (Volume XXVI, Part one, pp. 361-365). Affiliated East-West Press Pvt.Ltd. New Delhi 110001. ISBN 81-85938-98-9 2. Ravindranath, B. K. (2000). Kalanady. In K.S. Singh (Ed.), People of India: Karnataka, (Volume XXVI, Part one, pp. 536-540). Affiliated East-West Press Pvt.Ltd. New Delhi 110001. ISBN 81-85938-98-9 3. Ravindranath, B. K. (2000). Karimpalan (SC). In K.S. Singh (Ed.), People of India: Karnataka, (Volume XXVI, Part one, pp. 583-587). Affiliated East-West Press Pvt.Ltd. New Delhi 110001. ISBN 81-85938-98-9 4. Ravindranath, B. K. (2000). Kidaran. In K.S. Singh (Ed.), People of India: Karnataka, (Volume XXVI, Part one, pp. 606-611). Affiliated East-West Press Pvt.Ltd. New Delhi 110001. ISBN 81-85938-98-9 5. Ravindranath, B. K. (2000). Koraga (ST). In K.S. Singh (Ed.), People of India: Karnataka, (Volume XXVI, Part one, pp. 652-657). Affiliated East-West Press Pvt.Ltd. New Delhi 110001. ISBN 81-85938-98-9 6. Ravindranath, B. K. (2000). Kunduvadian. In K.S. Singh (Ed.), People of India: Karnataka, (Volume XXVI, Part one, pp. -

July 2021.Pmd

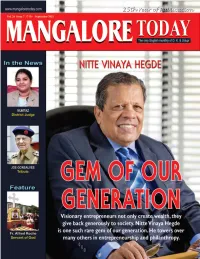

MANGALORE TODAY - SEPTEMBER 2021 1 2 MANGALORE TODAY - SEPTEMBER 2021 PPPOWER POINT PICTURE OF THE MONTH Hands-on Experience! Union Minister of State for Agriculture and Farmers' Welfare Shobha Karandlaje joins farmers in cultivating a fallow land at Kadekar village in Udupi as part of Hadilu Bhoomi Revival Scheme. ““““““ WWWORDSWORTH ”””””” “We must break the walls of “The musical world has caste, religion, superstitions the immense power to as well as mistrust that attract lakhs of people as create impediments in the music plays a very key role path of our progress” in enlivening our minds Prof Sabeeha B.Gowda, Professor, Dept of and hearts” Kannada Studies of Mangalore University at noted singer Ajay Warrior at the inaurual of a farewell ceremony on the occasion of her “Knowledge of local Karavali Music Camp in Mangaluru. retirement from service. languages will go a long way in assisting the police “Ranga Mandiras need to be “Man can lead a peaceful to efficiently maintain law protected if we have to life when he incorporates and order as well as in preserve and promote the good values and shuns his investigation of crimes” theatrical field” ego” City Police Commissioner N Shashi eminent Kannada movie director Rajendra Prof. P S Yadapadittaya, Vice Chancellor of Kumar at the inaugural of the month Singh Babu while launching the fund raising Mangalore University at the Kanaka lecture long Tulu learning workshop for police drive for the renovation of Don Bosco Hall in series at the University. officers and personnel. Mangaluru. MANGALORE TODAY - SEPTEMBER 2021 3 EEEDITOR’’’SSS EDGE VOL 24 ISSUE 7 SEPTEMBER 2021 Publisher and Editor V. -

Newsletter July-December 2011

Vol. 18 July-December 2011 No. 2 Taking a periodic review of the activities in the Institute helps in understanding the direction and pace of academic work as well as identifying the problem areas to be tackled in the course of development of the Institute. This exercise should not be taken as a routine drill but it should provide us a path for comparative understanding of our own accomplishments and shortfalls. I am happy that during the past six months, the activities in the Institute have sustained the earlier pace and pattern. An important task of faculty evaluation has been completed satisfactorily and provided good inputs for the faculty members and the Board of Governors. All the faculty colleagues cooperated and participated in the process of evaluation wholeheartedly and, I hope, they were able to pick up a few threads to move further towards excellence. I am quite pleased to record here the activities undertaken in the past six months with a sense of fulfillment, happiness as well as to kindle our thinking for future. From the During the last six months, the faculty and staff of the Institute were busy with a number Director’s Desk . of seminars, research projects and other academic activities. In this period, we organised 22 seminars at the Institute, averaging almost three events a month. These were attended by the faculty members as also invitees from outside. There were eight important events including a Training Programme in Econometrics for officers belonging to Indian Statistical Services; an International Post-Graduate Course on ‘Approaching the Environment in India – Issues and Methods in the Study of the Nature-Economy-Society Interface’ for the students from Nordic I am satisfied with this countries; another Training Workshop organised jointly with the University of Groningen, pace… but that does the Netherlands, on ‘Qualitative Data Analysis on Population Studies’. -

Caste Politics and State Integration: a Case Study of Mysore State

MAHESH RAMASWAMY, ASHA S. Caste Politics and State Integration... 195 DOI: 10.1515/ijas-2015-0009 MAHESH RAMASWAMY DVS EVENING COLLEGE ASHA. S GOVERNMENT FIRST GRADE COLLEGE Caste Politics and State Integration: a Case Study of Mysore State Abstract: The subject of unifi cation is as vibrant as national movement even after 58 years of a fractured verdict. More than to achieve a physical conjugation it was an attempt for cultural fusion. The aspiration for linguistic unifi cation was a part of the national discourse. The movement, which began with mystic originations, later on turned out to become communal. Political changes during 1799 A.D. and 1857 A.D. changed the fortunes of Mysore state and ultimately led to its disintegration and became the reason for this movement. The concept of unifi cation is akin to the spirit of nationalism, against the background of colonial regime assigning parts of land to different administrative units without taking into consideration the historical or cultural aspects of that place. Kannadigas marooned in multi lingual states experient an orphaned situation got aroused with the turn of nineteenth century. The problem precipitated by the company was diluted by British when they introduced English education. Though the positive aspect like emergence of middle class is pragmatic, rise of communalism on the other hand is not idealistic. This research paper is designed to examine the polarization of castes during unifi cation movement of Mysore State (Presently called as State of Karnataka, since 1973, which was termed Mysore when integrated) which came into being in 1956 A.D. -

Battles for Bangalore: Reterritorialising the City Janaki Nair Centre for the Study of Culture and Society Bangalore, India

Battles for Bangalore: Reterritorialising the City Janaki Nair Centre for the Study of Culture and Society Bangalore, India A divided city, cleaved by a swathe of parkland and administrative buildings that runs from north west to south east, was united in the single Bangalore City Corporation in 1949.1 No longer did the Bangalore Civil and Military station (referred to as the Cantonment, and the location since 1809 of British troops and their followers), have a separate administration from the old city area. And not just a geographical unity was forged, since the maps of linguistic, cultural and political traditions were redrawn. A previous move to unite the Cantonment, then under the control of the British Resident, with the rest of Princely Mysore was resisted by several cultural and economic groups that had long resided in the Station and enjoyed the perquisites of serving the colonial masters.2 A flurry of petitions protested the proposed "retrocession" of 1935 which would bring the Bangalore Cantonment under the Mysore administration; only the war delayed this move until July 1947.3 By 1949, such petitions were no deterrent to the plans of the new masters. But in the five decades since the formation of the Bangalore corporation, the city's east-west zonation continues to persist, and the uncomfortable question of "independence"4, or at least administrative freedom of the erstwhile cantonment has often been reiterated5. Most frequently, this has been in response to emerging cultural and political movements that seek to reterritorialise the city, refashioning its symbols, monuments or open spaces to evoke other memories, or histories that reflect the triumphs of the nation state, the hopes and aspirations of linguistic nationalisms or of social groups who have long lacked either economic or symbolic capital in the burgeoning city of Bangalore. -

KARNATAKA STATE MANDYA DISTRICT (Revised Edition)

GAZETTEER OF INDIA KARNATAKA STATE MANDYA DISTRICT (Revised Edition) GAZETTEER OF INDIA KARNATAKA STATE GAZETTEER MANDYA DISTRICT (Revised Edition) Chief Editor S.A.Jeelani, K.A.S. Mandya District Gazetteer - An English version of the Revised Kannada Edition Published in 2003. A PUBLICATION OF THE GOVERNMENT OF KARNATAKA © Government of Karnataka Office of the Chief Editor Karnataka Gazetteer Department Eighth Floor, BWSSB Building Cauvery Bhavan Bengaluru - 560 009. 2009 Price : Rs. Copies available at : Director Office of the Chief Editor Government Central Book Depot Karnataka Gazetteer Department First Floor, MS Building, Block-I Eighth Floor, BWSSB Building Dr. Ambedkar Veedhi Cauvery Bhavan, Bengaluru -560009. Bengaluru - 560 001. : 22213474 / Fax : 22243293 E-mail : [email protected]; [email protected] website : http:|| kar.nic.in/gazetteer Deputy Director : Government Branch Press, Panaji Road, Dharwad Ph : 2748145 Deputy Director : Government Branch Press Gulbarga. Joint Director : Government Branch Press, Saraswatipuram, Mysore Ph : 0821 - 2540684. Printed at : M/s Lavanya Mudrana No.19, 15th Cross, Banashankari I Stage Bengaluru - 560 050. : 26610563 iv From Secretary’s Desk Gazetteers are normally described as Geographical Encyclopaedias and a veritable voyage of discovery of a given area or region. The word ‘Gaza’ is from the Greek root meaning dictionary of places and the European countries introduced this in the format of Gazetteers. Under the British administration the compilation, editing, and publication of District Gazetteers was introduced in India. But, India had a grand tradition of preparing and publishing this type of works such as Kautalya’s Arthashastra, Varahamihira’s Brihat Samhitha and Abul Fazal’s Ain-i-Akbari, etc. -

Ethnographic Profile of Tribes in Karnataka

ANTHROPOLOGY BY DR ARJUN BOPANNA HANDOUT- 7 Ethnographic Profile of Tribes in Karnataka The State of Karnataka, is the home to 42,48,987 tribal people, of whom 50,870 belong to the primitive group. Although these people represent only 6.95 per cent of the population of the State, there are as many as 50 different tribes notified by the Government of India, living in Karnataka, of which 14 tribes including two primitive ones, are primarily natives of this State. Extreme poverty and neglect over generations have left them in poor state of health and nutrition. Unfortunately, despite efforts from the Government and non-Governmental organizations alike, literature that is available to assess the state of health of these tribes of the region remains scanty. It is however, interesting to note that most of these tribes who had been original natives of the forests of the Western Ghats have been privy to an enormous amount of knowledge about various medicinal plants and their use in traditional/folklore medicine and these practices have been the subject matter of various scientific studies. Kannada is the most widely spoken and official language of the State. Apart from Kannadigas, Karnataka is the home to Tuluvas, Kodavas and Konkanis along with minor populations of Tibetan Buddhists. Although there are other ethnic tribes, the Scheduled Tribe population comprises some of the better known tribes like the Soligas, Yeravas, Todas and Siddhis and constitute 6.95 per cent of the total population of Karnataka Currently there are 50 Scheduled Tribes (ST) in Karnataka notified according to the Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order (Amendment) Act 2003. -

Literature and Culture 739

Literature and Culture 739 CHAPTER XIV LITERATURE AND CULTURE Mandya district is known in the Puranas to have been a part of Dandakaranya forest. It is said there that sages such as Mandavya, Mytreya, Kadamba, Koundliya, Kanva, Agasthya, Gautama and others did penance in this area. Likewise, literature and cultural heritage also come down here since times immemorial. The district of Mandya is dotted with scenic spots like Kunthibetta, Karighatta, Narayanadurga, Gajarajagiri, Adicunchanagiri and other hills; rivers such as Kaveri, Hemavathi, Lokapavani, Shimsha and Viravaishnavi; waterfalls like Gaganachukki, Bharachukki and Shimha; and bird sanctuaries like Ranganathittu, Kokkare Bellur and Gendehosalli, which are sure to have influenced the development of literature and culture of this area. Places like Srirangapattana, Nagamangala, Malavalli, Melukote, Tonnur, Kambadahalli, Bhindiganavile, Govindanahalli, Bellur, Belakavadi, Maddur, Arethippur, Vydyanathapura, Agrahara Bachahalli, Varahnatha Kallahalli, Aghalaya, Hosaholalu, Kikkeri, Basaralu, Dhanaguru, Haravu, Hosabudanuru, Marehalli and others were centers of rich cultural activities in the past. In some places dissemination of knowledge and development of education, arts and spiritual pursuits were carried out by using temples as workshops. Religious places such as Tonnur and Melukote from where Ramanujacharya, who propounded Srivaishanva philosophy; Arethippur, 740 Mandya District Gazetteer Kambadahalli and Basthikote, the centers of Jainism; the temples of Sriranganatha and Gangadharanatha