Appendixc.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oliver Twist

APPENDIX B Summary of Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist In a parish workhouse, a nameless young woman dies after giving birth. Her son, Oliver Twist—as named by the beadle, Mr. Bumble—is sent to a separate branch of the workhouse with other orphaned infants and raised by the monstrous Mrs. Mann. Oliver miraculously survives the horrors of the “baby farm,” and, on his ninth birthday, is transferred to the central workhouse. After three months of slow starvation, the boys draw lots to see who will ask for more gruel; Oliver draws the long straw and carries out this unenviable task. Bumble and the board of directors severely punish Oliver and plan to turn him out of the workhouse. After a failed attempt to apprentice him to a brutal chimney sweep, Bumble eventually manages to unload Oliver on Mr. Sowerberry, the undertaker. On top of his depressing new trade, Oliver must deal with the bullying of his fel- low apprentice, Noah Claypole. Oliver finally fights back against Noah when his rival taunts him about his deceased mother. This second “rebellion” earns Oliver a stern rebuke from Bumble and a brutal beating from Sowerberry. Consumed by the misery of his life, Oliver decides to run away, though he first returns to the baby farm to bid goodbye to his friend, Dick. Oliver barely survives the seventy-five mile walk to London. On arriving at Barnett, he encounters a strangely attired cockney boy who introduces himself as Jack Dawkins (though he goes by the name of the Artful Dodger). The Dodger invites Oliver to come and lodge with a respectable old gentleman, and he conducts a wary Oliver through the slums of London to a dilapidated flat. -

And Charles Dickens' Oliver Twist

A OUEY OUG E UEWO I SAI A EGA RINC'ONETE Y CORTADILLO A OIE TWIST EOAI-I IEICK UIESIA E AAOI eoayuaes E Oliver Twist, C ickes se eaya e ua cíica e as coicioes sociaes e a Igaea e sigo I cuya uea aía eeimeao e iño E uuo e Oie u oe uéao se eae ee as gaas e ama y a iáaa ia e a cases acomoaas E Rinconete y Cortadillo, uicao o Migue e Ceaes e 113 ceemos e e uo e aia e a eesa oea e ickes Ese aícuo esuia os uos e coaco ee amas oas o que oiga a ua eeió soe as caaceísicas e géeo y amié ua iagació e a iuecia e Ceaes e a ieaua igesa Caes ickes ook i uo imse o ciicie e socia coiios i 19 ceuy Ega o wic e imse as a ci a ee a oeia icim i e soy o Oie wis a youg oa wose uue as a eique o a uig meme o sociey is e suec o eae a iigue Rinconete and Cortadillo, wie wo ceuies eaie y Migue e Ceaes wou seem o e a saig oi o ickes Oliver Twist as umeous ois o coac ca e ieiie is eas o e quesio o e caaceisics o gee as we as e iuece o Ceaes o Egis ieaue A cose eaig o Migue e Ceaes Rinconete y Cortadillo (113 a Caes ickes Oliver Twist (137-139 igs o ig a seies o eemes wic wou o seem o oey o mee coiciece Ee gie e ieeces ewee Goe Age Seiia sociey a eay 19á ceuy oo a commo ea aiuae o Exemplaria 6, 1-9 ISS 113-19 © Uiesia e uea Universidad de Huelva 2009 82 EOA IEICK sae iogaica eeieces a a commo ouook o ie ueies o woks o is mus e ae o e eouio o e icaesque oe a e ieay aiio o Ceaes a is woks i Ega o oy wi eeece o ickes imse u aso o e iis wies wo iuece im Seie i e 1h a 17h ceuies was a meig o a aace eoe om may couies a a waks o ie Ayoe esiig o emak o Sais ew Wo eioies was -

Hunger for Life in Oliver Twist Novel

www.ijcrt.org © 2018 IJCRT | Volume 6, Issue 4 October 2018 | ISSN: 2320-2882 HUNGER FOR LIFE IN OLIVER TWIST NOVEL Karabasappa Channappa Nandihally Assistant Professor Of English Government First Grade College, U.G.&P.G.Centre Dental College Road,Vidyanagar,Davanagere. Abstract This novel focusing on Poverty is a prominent concern in Oliver Twist. Throughout the novel, Dickens enlarged on this theme, describing slums so decrepit that whole rows of houses are on the point of ruin. In an early chapter, Oliver attends a pauper's funeral with Mr. Sowerberry and sees a whole family crowded together in one miserable room.This prevalent misery makes Oliver's encounters with charity and love more poignant. Oliver owes his life several times over to kindness both large and small.[14] The apparent plague of poverty that Dickens describes also conveyed to his middle-class readers how much of the London population was stricken with poverty and disease. Nonetheless, in Oliver Twist, he delivers a somewhat mixed message about social caste and social injustice. Oliver's illegitimate workhouse origins place him at the nadir of society; as an orphan without friends, he is routinely despised. His "sturdy spirit" keeps him alive despite the torment he must endure. Most of his associates, however, deserve their place among society's dregs and seem very much at home in the depths. Noah Claypole, a charity boy like Oliver, is idle, stupid, and cowardly; Sikes is a thug; Fagin lives by corrupting children, and the Artful Dodger seems born for a life of crime. Many of the middle-class people Oliver encounters—Mrs. -

Oliver Twist~

OLIVER TWIST~ A Family Musical Adapted from the Novel by Charles Dickens Music & Lyrics by MICHAEL LANCY Book by MICHAEL LANCY & CHUCK LAKIN CENTERSTAGE PRESS, INC. Phoenix Arizona OLIVER TWIST Copyright 1976 by Michael Lancy Copyright 1981 by Michael Lancy & Chuck Lakin Printed in U.S.A. ISBN: 1-890298-27-1 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Warning: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that OLIVER TWIST is subject to royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, the British Empire, including the Dominion of Canada, and all other countries of the Copyright Union. All rights, including professional, amateur, motion pictures, recita- tion, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, and the rights of transla- tion into foreign languages are strictly reserved. For all rights apply to CENTERSTAGE PRESS, www.centerstagepress.com, (602) 242-1123. Copying from this script, in whole or in part, by any means is strictly forbidden by law and the right of performance is not transferable. Particular emphasis is laid on the ques- tion of amateur or professional readings, permission and terms for which must be secur- ed in written form from Centerstage Press, Inc. Whenever this play is produced the following notice must appear on all programs, printing and advertising for the play: “Produced by special arrangement with Centerstage Press.” Due authorship credit must be given on all programs, printing and advertising for the play. NO CHANGES SHALL BE MADE IN THE PLAY FOR THE PURPOSE OF YOUR PRODUCTION UNLESS AUTHORIZED IN WRITING. ~ CHARACTERS ~ MR. BUMBLE: A portly man of middle age, Bumble fancies himself a man of some great importance and distinction. -

Oliver Twist Co-Planning: Fagin T14/F16

Oliver Twist Co-planning: Fagin T14/F16 Subject knowledge development Mastery Content for Fagin lesson Review this mastery content with your teachers. Be aware that the traditional and foundation pathways are very different for this lesson. Foundation Traditional • Oliver wakes up and notices Fagin looking at his jewels and Fagin snaps at him in a threatening way. • The meaning of the word villain • Fagin is a corrupt villain • Fagin is selfish. • Fagin teaches Oliver a new game: how to pick pockets. • Oliver doesn’t realise Fagin is a villain • Fagin is a villain because he tricks Oliver into learning how to • Fagin is a corrupt villain steal. • Nancy and Bet arrive and Oliver thinks Nancy is beautiful. Start at the end. Briefly look through the lesson materials for this lesson in your pathway, focusing in particular on the final task before the MCQ: what will be the format of this final task before the MCQ with your class? Get teachers to decide what they want the final task before the MCQ to look like in their classroom. What format will it take? It would be good to split teachers into traditional and foundation pathway teachers at this point. Below is a list of possible options that you could use to steer your teachers: • Students write an analytical paragraph about Fagin as a villain (traditional) • Students write a bullet point list of what evidence suggests Fagin is a villain (traditional) • Students write a paragraph about how Fagin is presented in chapter 10 (foundation). • Students explode a quotation from chapter 10 explaining how Fagin is presented. -

“The Other Woman” – Eliza Davis and Charles Dickens

44 DICKENS QUARTERLY “The Other Woman” – Eliza Davis and Charles Dickens MURRAY# BAUMGARTEN University of California, Santa Cruz he letters Eliza Davis wrote to Charles Dickens, from 22 June 1863 to 8 February 1867, and after his death to his daughter Mamie on 4 August 1870, reveal the increasing self-confidence of English Jews.1 TIn their careful and accurate comments on the power of Dickens’s work in shaping English culture and popular opinion, and their pointed discussion of the ways in which Fagin reinforces antisemitic English and European Jewish stereotypes, they indicate the concern, as Eliza Davis phrases it, of “a scattered nation” to participate fully in the life of “the land in which we have pitched our tents.2” It is worth noting that by 1858 the fits and starts of Jewish Emancipation in England had led, finally, to the seating of Lionel Rothschild in the House of Commons. After being elected for the fifth time from Westminster he was not required, due to a compromise devised by the Earl of Lucan and Benjamin Disraeli, to take the oath on the New Testament as a Christian.3 1 Research for this paper could not have been completed without the able and sustained help of Frank Gravier, Reference Librarian at the University of California, Santa Cruz, Assistant Librarian Laura McClanathan, Lee David Jaffe, Emeritus Librarian, and the detective work of David Paroissien, editor of Dickens Quarterly. I also want to thank Ainsley Henriques, archivist of the Kingston Jewish Community of Jamaica, Dana Evan Kaplan, the rabbi of the Kingston Jewish community, for their help, and the actress Miryam Margolyes for leading the way into genealogical inquiries. -

“Reviewing the Situation”: Oliver! and the Musical Afterlife of Dickens's

“Reviewing the Situation”: Oliver! and the Musical Afterlife of Dickens’s Novels Marc Napolitano A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by Advisor: Allan Life Reader: Laurie Langbauer Reader: Tom Reinert Reader: Beverly Taylor Reader: Tim Carter © 2009 Marc Napolitano ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Marc Napolitano: “Reviewing the Situation”: Oliver! and the Musical Afterlife of Dickens’s Novels (Under the direction of Allan Life) This project presents an analysis of various musical adaptations of the works of Charles Dickens. Transforming novels into musicals usually entails significant complications due to the divergent narrative techniques employed by novelists and composers or librettists. In spite of these difficulties, Dickens’s novels have continually been utilized as sources for stage and film musicals. This dissertation initially explores the elements of the author’s novels which render his works more suitable sources for musicalization than the texts of virtually any other canonical novelist. Subsequently, the project examines some of the larger and more complex issues associated with the adaptation of Dickens’s works into musicals, specifically, the question of preserving the overt Englishness of one of the most conspicuously British authors in literary history while simultaneously incorporating him into a genre that is closely connected with the techniques, talents, and tendencies of the American stage. A comprehensive overview of Lionel Bart’s Oliver! (1960), the most influential Dickensian musical of all time, serves to introduce the predominant theoretical concerns regarding the modification of Dickens’s texts for the musical stage and screen. -

Answer Sheet

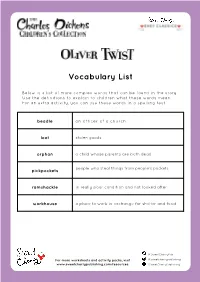

Vocabulary List Below is a list of more complex words that can be found in the story. Use the definitions to explain to children what these words mean. For an extra activity, you can use these words in a spelling test. beadle an officer of a church loot stolen goods orphan a child whose parents are both dead people who steal things from people’s pockets pickpockets ramshackle in really poor condition and not looked after workhouse a place to work in exchange for shelter and food @SweetCherryPub For more worksheets and activity packs, visit @sweetcherrypublishing www.sweetcherrypublishing.com/resources. /SweetCherryPublishing Plot Sequencing Answer Sheet 1. Oliver Twist is forced out of the workhouse for asking for more food. The Sowerberrys take him in but treat him horribly. 2. Oliver runs away from the Sowerberrys and spends a week walking to London. 3. Oliver meets the Artful Dodger who introduces him to Fagin’s gang. 4. Oliver is accused of stealing with the gang and the police arrest him. 5. The Brownlows take Oliver in while he recovers from a fever. 6. Bill Sikes finds Oliver and brings him back to the gang. 7. The police come to arrest Fagin. Everyone splits up and runs away. 8. Oliver returns to the Brownlows and learns more about his real family. @SweetCherryPub For more worksheets and activity packs, visit @sweetcherrypublishing www.sweetcherrypublishing.com/resources. /SweetCherryPublishing Reading Comprehension Answer Sheet Q1: What was Oliver’s job at the workhouse? Answer: To unpick old tar-covered strands of ship’s rope so the fibre could be used again. -

Download This PDF File

Copyright © 2020 The Author IDEAS IDEAS is licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0 License Journal of Language Teaching and Learning, Linguistics and Literature Issued by English study program of IAIN Palopo ISSN 2338-4778 (Print) ISSN 2548-4192 (Online) Volume 8, Number 1, June 2020 pp. 217 – 229 Fagin’s Criminal Thought in Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist Rahmi Munfangati*1, Desi Ramadhani2 * [email protected] 1,2 Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Yogyakarta, Indonesia Received: 27 May 2020 Accepted:31 May 2020 DOI: 10.24256/ideas.v8i1.1351 Abstract This research aims to reveal Fagin’s criminal thought in Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist and to examine the factors that influence Fagin’s criminal thought presented in the novel. This research is classified into library research. The subject of the research is Oliver Twist, Charles Dickens’ fiction novel. The novel is used as the primary source, while books, journals, and articles related to criminal thought theories in psychology were taken as the secondary source. A psychological approach is applied to analyze the data. The collected data were analyzed qualitatively. In analyzing the data, the researcher took five steps. The data were collected from reading and re-reading the text, identifying those that embody criminal thinking, categorizing them based on the objectives of the research, comparing them to the theoretical frameworks, and finally interpreting them using a psychological approach. After conducting the research, it can be drawn some conclusions; first, by seeing the eight aspects of criminal thought, Fagin has five aspects which are classified in the high category, and second, the factors that influence Fagin’s criminal thought reflected in the novel are societal and economic, neighbor-hood and local institutions, and drugs. -

Year 7 English Oliver Twist Student Workbook

Student Name: _____________________________________ Year 7 English Oliver Twist Student Workbook A special thanks to Mona Maret, Ark Globe Academy for the adaption and formatting of this material. This workbook has been created to follow the English Mastery 4Hr Traditional Curriculum. This workbook is an optional supplement and should not replace the standard English Mastery resources. It is specifically designed to provide consistency of learning, should any students find their learning interrupted. Due to the nature of the format – some deviations have been made from the EM Lesson ppts. These have been made of necessity and for clarity. Guide for Teachers - Mona Maret, Ark Globe This workbook was designed to function primarily as an independent resource. However, it can be – and is recommended to be – used in the classroom, alongside the lessons, where it can become a valuable tool for quality learning and teaching. It contains all the information provided in the Mastery lessons, the tasks that the students are required to complete and the writing space to complete these tasks. Therefore, it not only has all the information and resources from the lessons, but also the students’ own work. This will give the teacher a clear image of how the students have understood and assimilated the content while also providing the students with an excellent revision tool. However, as this workbook was created first and foremost in the event that students would be forced to work without a teacher, the following elements were heavily factored into its design: 1. Independence – trying to ensure that students could work through the workbook and understand as much of the content as possible on their own. -

Oliver Twist

Oliver Twist Charles Dickens Written in 1838, this is the story of a young orphan, Oliver, who runs away to London and meets up with another boy, Jack Dawkins, known as the ARTFUL DODGER. The DODGER introduces Oliver to the sinister Fagin, who runs a Thieves Den, sending out young boys to pick the pockets of the rich. In this scene, Oliver is on his knees cleaning the DODGER's boots for him, while DODGER explains the advantages of joining Fagin s gang. Although the DODGER is young and only four foot six tall, he has all the airs and manners of a man about town. DODGER (Sighs and resumes his pipe) I suppose you don't even know what a prig is? ... I am. I'd scorn to be anything else. So's Charley. So's Fagin. So's Sikes. So's Nancy. So's Bet. So we all are, down to the dog. And he's the downiest one of the lot! He wouldn't so much as bark in a witness-box for fear of committing himself; no, not if you tied him up in one, and left him there without wittles for a fortnight. He's a rum dog. Don't he look fierce at any strange cove that laughs or sings when he's in company! Won't he growl at all, when he hears a fiddle playing! And don't he hate other dogs as ain't of his breed! - Oh no! He's an out-and-out Christian . Why don't you put yourself under Fagin, Oliver? And make a fortun' out of hand? And so be able to retire on your property, and do the gen-teel; as I mean to, in the very next leap-year but four that ever comes, and the forty-second Tuesday in Trinity-week .. -

The Antagonist Character's Criminal Thought in Charles Dickens' Oliver Twist

THE ANTAGONIST CHARACTER’S CRIMINAL THOUGHT IN CHARLES DICKENS’ OLIVER TWIST Desi Ramadhani [email protected] English Education Department Universitas Ahmad Dahlan ABSTRACT This thesis entitled The Antagonist Character’s Criminal Thought in Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist: A Psychological Approach . There are two objectives in this research. Those are: to describe the antagonist character’s criminal thought in Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist and to explain the factors that influence the antagonist character’s criminal thought presented in the novel. In this thesis, the researcher takes a library research. The subject of the research is Oliver Twist, a fiction novel by Charles Dickens. The novel is used as the primary source, while books, journals, and articles are taken as the secondary source. The data were collected by visiting libraries, reading, taking notes, and categorizing data. Then, the researcher applied a psychological approach to analyze the data. The collected data were analyzed qualitatively in the form of statements and sentences. After conducting the research, the researcher comes to the conclusion that first, from the eight aspects of criminal thought, Fagin has five aspects which are classified in the high category, Fagin is intended as the criminal masterpiece in Oliver Twist novel. Second, the factors that influence the antagonist character’s criminal thought in Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist are societal & economic factors, neighbor-hood and local institutions, and drugs. Keywords: Criminal thought, psychological approach, Fagin, Oliver Twist 1 2 I. INTRODUCTION Criminal is a crime in the form of thoughts or ideas without using physical violence. In a problem, an idea is the most important thing because without an idea, a thing cannot happen or be carried out.