At the Core Ofa Dynamic New York City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Where Architecture Expert Paul Goldberg Comments on the History of New York's Famous Skyscrapers. As You Do So, Complete

Can you identify any of these buildings? What do they all have in common? Which one do you like best? Read where architecture expert Paul Goldberg comments on the history of New York’s famous skyscrapers. As you do so, complete the following tasks: · In New York buildings are not only buildings, they become ___________________ · New York took over Chicago as regards skyscrapers in ___________________. · The Woolworth building was the tallest building worldwide for _________________. · The _______________ defined the Manhattan skyline. · They are trying to keep a memory of the people who were lost and also to show New York’s ______________________________. · New York stands out from the other cities as the embodiment of ____________________. Woolworth Building; Empire State Building; Chrysler Building; Flatiron; Hearst Tower The Woolworth Building, at 57 stories (floors), is one of the oldest—and one of the most famous—skyscrapers in New York City. It was the world’s tallest building for 17 years. More than 95 years after its construction, it is still one of the fifty tallest buildings in the United States as well as one of the twenty tallest buildings in New York City. The building is a National Historic Landmark, having been listed in 1966. The Empire State Building is a 102-story landmark Art Deco skyscraper in New York City at the intersection of Fifth Avenue and West 34th Street. Like many New York building, it has become seen as a work of art. Its name is derived from the nickname for New York, The Empire State. It stood as the world's tallest building for more than 40 years, from its completion in 1931 until construction of the World Trade Center's North Tower was completed in 1972. -

One West End, 432 Park Avenue, and One57 Are the Top-Selling Condo Buildings in New York City So Far This Year, According to Research from Cityrealty

By CityRealty Staff Friday, July 13, 2018 L to R: One West End, 432 Park Avenue, One57 One West End, 432 Park Avenue, and One57 are the top-selling condo buildings in New York City so far this year, according to research from CityRealty. Closings in the three buildings together have accounted for more than half a billion dollars in sales. Recorded sales in One West End so far this year have totaled $207 million over 57 units. The average sales price in the building this year is $3.6 million, and the average price/ft2 is $2,064. The Elad Group and Silverstein Properties-developed building, where closings started last year, is approaching sell-out status, with 193 of the 246 units having closed already, including one four-bedroom now belonging to Bruce Willis and his wife Emma Heming Willis. // One West End interiors (DBOX / Pelli Clarke Pelli Architects) https://www.cityrealty.com/nyc/market-insight/features/get-to-know/2018039s-top-selling-condos-so-far-one-west- end-beats-432-park-avenue/19263 Even though there have only been 8 closings recorded so far this year in 432 Park Avenue, the world's tallest residential building is the second-highest selling building of 2018 so far, with $185 million in sales. The average price of the closed sales in 432 Park this year is $23.1 million, while the average price/ft2 is $6,509. J.Lo & A-Rod's new condo (Douglas Elliman) In February, developers CIM Group and Macklowe Properties announced that the Billionaire's Row supertall is the single best-selling building in New York City, with $2 billion under its belt at the time. -

Murdoch's Global Plan For

CNYB 05-07-07 A 1 5/4/2007 7:00 PM Page 1 TOP STORIES Portrait of NYC’s boom time Wall Street upstart —Greg David cashes in on boom on the red hot economy in options trading Page 13 PAGE 2 ® New Yorkers are stepping to the beat of Dancing With the Stars VOL. XXIII, NO. 19 WWW.NEWYORKBUSINESS.COM MAY 7-13, 2007 PRICE: $3.00 PAGE 3 Times Sq. details its growth, worries Murdoch’s about the future PAGE 3 global plan Under pressure, law firms offer corporate clients for WSJ contingency fees PAGE 9 421-a property tax Times, CNBC and fight heads to others could lose Albany; unpacking out to combined mayor’s 2030 plan Fox, Dow Jones THE INSIDER, PAGE 14 BY MATTHEW FLAMM BUSINESS LIVES last week, Rupert Murdoch, in a ap images familiar role as insurrectionist, up- RUPERT MURDOCH might bring in a JOINING THE PARTY set the already turbulent media compatible editor for The Wall Street Journal. landscape with his $5 billion offer for Dow Jones & Co. But associ- NEIL RUBLER of Vantage Properties ates and observers of the News media platform—including the has acquired several Corp. chairman say that last week planned Fox Business cable chan- thousand affordable was nothing compared with what’s nel—and take market share away housing units in the in store if he acquires the property. from rivals like CNBC, Reuters past 16 months. Campaign staffers They foresee a reinvigorated and the Financial Times. trade normal lives for a Dow Jones brand that will combine Furthermore, The Wall Street with News Corp.’s global assets to Journal would vie with The New chance at the White NEW POWER BROKERS House PAGE 39 create the foremost financial news York Times to shape the national and information provider. -

A – SMOKE and MIRRORS (The United Nations Building to Grand

SMOKE AND MIRRORS (The United Nations to Grand Central Station) ____________________________________________ At the edge of the world sits a Tower. And this Tower is no structure of brick and mortar, but a kind of illusion; a trick of the light, flickering electric blue in and out of sight; a coalescing of vapors; of misplaced goodwill. The kings and queens of the world attend here, pronouncing PEACE, while raining armaments on those of their own, or those of their own they believe to be not. But still the pilgrims come in the thousands from the Terminal seeking an audience, uninformed or disregarding of this Congregation’s inadequacy. Through miles of devastated landscape they come with their fragile appeals in their hands, towards the Tower shimmering like a mirage in the distance; and the mediaeval brick city-fortress that guards its flanks. Around them, light and shadow play upon pillars of glass and steel, reflected one upon the other so reality is indiscernible from reflection; so the pilgrim, his eyes confused and diverted, does not realise that there is in fact, nothing behind the smoke and mirrors; that this entire landscape of grandiose ideals is insubstantial. Ting 8 1 – The United Nations Secretariat Tower, completed in 1952 and designed by an international committee of architects, including Le Corbusier, Oscar Niemeyer, amongst others. Ting 9 2 – Isaiah 2:4, on the Scharansky steps, named after a Soviet dissident, and part of the Ralphe Bunche Park. This park is across from the UN complex. 3 – Channelling Hampton Court: Tudor City, a luxury residential project built between 1925-28, by the Fred F. -

General Info.Indd

General Information • Landmarks Beyond the obvious crowd-pleasers, New York City landmarks Guggenheim (Map 17) is one of New York’s most unique are super-subjective. One person’s favorite cobblestoned and distinctive buildings (apparently there’s some art alley is some developer’s idea of prime real estate. Bits of old inside, too). The Cathedral of St. John the Divine (Map New York disappear to differing amounts of fanfare and 18) has a very medieval vibe and is the world’s largest make room for whatever it is we’ll be romanticizing in the unfinished cathedral—a much cooler destination than the future. Ain’t that the circle of life? The landmarks discussed eternally crowded St. Patrick’s Cathedral (Map 12). are highly idiosyncratic choices, and this list is by no means complete or even logical, but we’ve included an array of places, from world famous to little known, all worth visiting. Great Public Buildings Once upon a time, the city felt that public buildings should inspire civic pride through great architecture. Coolest Skyscrapers Head downtown to view City Hall (Map 3) (1812), Most visitors to New York go to the top of the Empire State Tweed Courthouse (Map 3) (1881), Jefferson Market Building (Map 9), but it’s far more familiar to New Yorkers Courthouse (Map 5) (1877—now a library), the Municipal from afar—as a directional guide, or as a tip-off to obscure Building (Map 3) (1914), and a host of other court- holidays (orange & white means it’s time to celebrate houses built in the early 20th century. -

New York by Gehry Architect Brochure

architect “I’ve always been fascinated with folds. All artists through the ages have spent time on the fold. Michelangelo had stacks of drawings of fabric. At 8 Spruce, we’re using Bernini’s folds to inspire the façade. I look for ways to express feeling in a building without using historic decoration.” Frank Gehry As varied as the cultural contexts in which he builds, Gehry’s muses include the natu- ral environment, clients, colleagues and artists from a variety of eras and disciplines. When seeking inspiration Gehry has spoken of turning to classic art, and, especially, to paintings, which he has said are ephemeral, open to interpretation and filled with ideas. However, for New York by Gehry, he was initially particularly inspired by Michelan- gelo’s drawings of fabric, which suggested the design of a very curvaceous, voluptuous façade. Later, in an early morning epiphany, Gehry recalled the work of 17th century Italian artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini and the design took a new direction. Gehry’s fascination with Bernini dates back to 1960 when he first saw Bernini’s masterful sculpture, the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, in the Cornaro Chapel in Santa Maria della Vittoria. This sculpture, which he now visits on annual trips to Rome, features Bernini’s signature sharp, elongated folds of flowing fabric. The morning after his epiphany, Gehry went to a young designer in his office and asked her if she knew the difference between “Michelangelo curves and Bernini curves.” She said that she did, and within a matter of hours she delivered the sketch that led to the first model of New York by Gehry. -

CHRYSLER BUILDING, 405 Lexington Avenue, Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 12. 1978~ Designation List 118 LP-0992 CHRYSLER BUILDING, 405 Lexington Avenue, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1928- 1930; architect William Van Alen. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1297, Lot 23. On March 14, 1978, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a_public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Chrysler Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 12). The item was again heard on May 9, 1978 (Item No. 3) and July 11, 1978 (Item No. 1). All hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Thirteen witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were two speakers in opposition to designation. The Commission has received many letters and communications supporting designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Chrysler Building, a stunning statement in the Art Deco style by architect William Van Alen, embodies the romantic essence of the New York City skyscraper. Built in 1928-30 for Walter P. Chrysler of the Chrysler Corporation, it was "dedicated to world commerce and industry."! The tallest building in the world when completed in 1930, it stood proudly on the New York skyline as a personal symbol of Walter Chrysler and the strength of his corporation. History of Construction The Chrysler Building had its beginnings in an office building project for William H. Reynolds, a real-estate developer and promoter and former New York State senator. Reynolds had acquired a long-term lease in 1921 on a parcel of property at Lexington Avenue and 42nd Street owned by the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. -

15-B William Van Alen, the Chrysler Building, 1926–1930

WILLIAM VAN ALEN [1883–1954] 15b The Chrysler Building, 1926–1930 The Chrysler Building could only have been constructed in the To make the Chrysler Building distinct from others of its kind, Van competitive climate of Manhattan in the 1920s. The American Alen chose motifs appropriate to the machine age, particularly economy was flourishing, and there was not enough office space the automobile. The spire’s gleaming stainless steel cladding calls to go around; urban builders were encouraged to aim high. In to mind the polished chrome of a brand new car. Stylized 1926, Walter P. Chrysler, one of the wealthiest men in the auto- American eagle heads protrude from some corners of the build- motive industry, entered his bid in the unofficial competition to ing in playful reference to the gargoyles on Gothic cathedrals. build the tallest structure in New York City. He wanted an office Other corners are embellished with the winged forms of a building exalted enough to symbolize his own astounding ascent Chrysler radiator cap. One ornamental frieze incorporates a in the business world. Brooklyn-born architect William Van Alen, band of hubcaps. who had a reputation for progressive, flamboyant design, met If the exterior ornament enhances the modernity of the sky- Chrysler’s challenge with a seventy-seven-story building, the first scraper, the interior was designed to recall the distant past, and in the world to exceed a height of one thousand feet. positions the Chrysler Building among the wonders of the The pyramidal form of the Chrysler Building was dictated by a world. -

October 2020 New York City Center

NEW YORK CITY CENTER OCTOBER 2020 NEW YORK CITY CENTER SUPPORT CITY CENTER AND Page 9 DOUBLE YOUR IMPACT! OCTOBER 2020 3 Program Thanks to City Center Board Co-Chair Richard Witten and 9 City Center Turns the Lights Back On for the his wife and Board member Lisa, every contribution you 2020 Fall for Dance Festival by Reanne Rodrigues make to City Center from now until November 1 will be 30 Upcoming Events matched up to $100,000. Be a part of City Center’s historic moment as we turn the lights back on to bring you the first digitalFall for Dance Festival. Please consider making a donation today to help us expand opportunities for artists and get them back on stage where they belong. $200,000 hangs in the balance—give today to double your impact and ensure that City Center can continue to serve our artists and our beloved community for years to come. Page 9 Page 9 Page 30 donate now: text: become a member: Cover: Ballet Hispánico’s Shelby Colona; photo by Rachel Neville Photography NYCityCenter.org/ FallForDance NYCityCenter.org/ JOIN US ONLINE Donate to 443-21 Membership @NYCITYCENTER Ballet Hispánico performs 18+1 Excerpts; photo by Christopher Duggan Photography #FallForDance @NYCITYCENTER 2 ARLENE SHULER PRESIDENT & CEO NEW YORK STANFORD MAKISHI VP, PROGRAMMING CITY CENTER 2020 Wednesday, October 21, 2020 PROGRAM 1 BALLET HISPÁNICO Eduardo Vilaro, Artistic Director & CEO Ashley Bouder, Tiler Peck, and Brittany Pollack Ballet Hispánico 18+1 Excerpts Calvin Royal III New York Premiere Dormeshia Jamar Roberts Choreography by GUSTAVO RAMÍREZ -

Advancing Women in Real Estate in the United States

Advancing Women in Real Estate in the United States i ADVANCING WOMEN IN REAL ESTATE IN THE UNITED STATES Table of Contents I. Overview of the Women’s Leadership Initiative II. Executive Summary III. Survey Results of Women in the Industry IV. Strategies to Promote Women V. Recommended Actions VI. Case Studies a. City of Dallas b. EDENS c. Forest City Ratner d. Gensler e. Prologis f. Pursley Friese Torgrimson VII. Research Approach VIII. Credits 1 ADVANCING WOMEN IN REAL ESTATE IN THE UNITED STATES Overview of the Women’s Leadership Initiative The Women’s Leadership Initiative (WLI) at the Urban Land Institute (ULI) was founded in 2011 to encourage greater diversity in the real estate and land use industry. A variety of global research demonstrates that gender diversity in a company’s leadership ranks correlates with improved per- formance compared with peer organizations that lack diversity. Economic research also illustrates the increased productivity possible if industry sectors fully use the female population in the work- force. Yet membership statistics for ULI reflect a lack of diversity, with only one in four members being a woman. In order to build a vibrant and sustainable organization, that lack of diversity must be addressed. The mission of WLI is to raise the visibility and number of women leaders at ULI and in the real estate industry. This mission is achieved through the following objectives: • Promote the advancement of women, throughout their careers, as leaders in the real estate industry. • Increase the number of women serving in leadership positions in the real estate industry and at ULI. -

True to the City's Teeming Nature, a New Breed of Multi-Family High Rises

BY MEI ANNE FOO MAY 14, 2016 True to the city’s teeming nature, a new breed of multi-family high rises is fast cropping up around New York – changing the face of this famous urban jungle forever. New York will always be known as the land of many towers. From early iconic Art Deco splendours such as the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building, to the newest symbol of resilience found in the One World Trade Center, there is no other city that can top the Big Apple’s supreme skyline. Except itself. Tall projects have been proposed and built in sizeable numbers over recent years. The unprecedented boom has been mostly marked by a rise in tall luxury residential constructions, where prior to the completion of One57 in 2014, there were less than a handful of super-tall skyscrapers in New York. Now, there are four being developed along the same street as One57 alone. Billionaire.com picks the city’s most outstanding multi-family high rises on the concrete horizon. 111 Murray Street This luxury residential tower developed by Fisher Brothers and Witkoff will soon soar some 800ft above Manhattan’s Tribeca neighborhood. Renderings of the condominium showcase a curved rectangular silhouette that looks almost round, slightly unfolding at the highest floors like a flared glass. The modern design is from Kohn Pedersen Fox. An A-team of visionaries has also been roped in for the project, including David Mann for it residence interiors; David Rockwell for amenities and public spaces and Edmund Hollander for landscape architecture. -

June 2014 Scope of Feasibility Study Evaluates Technical, Legal and Financial Feasibility of the Multi-Purpose Levee (MPL) Concept

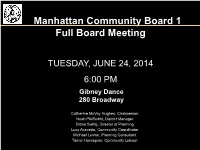

Manhattan Community Board 1 Full Board Meeting TUESDAY, JUNE 24, 2014 6:00 PM Gibney Dance 280 Broadway Catherine McVay Hughes, Chairperson Noah Pfefferblit, District Manager Diana Switaj, Director of Planning Lucy Acevedo, Community Coordinator Michael Levine, Planning Consultant Tamar Hovsepian, Community Liaison Manhattan Community Board 1 Public Session Comments by members of the public (6 PM to 7 PM) (Please limit to 1-2 minutes per speaker, to allow everyone to voice their opinions) Welcome: Gina Gibney, Chief Executive Officer & Artistic Director of Gibney Dance Guest Speaker: Frank McCarton, Deputy Commissioner of Operations, NYC Office of Emergency Management Making SPACE FOR CULTURE MANHATTAN COMMUNITY DISTRICT 1 PUBLIC SCHOOLS (DRAFT) Elementary School Middle School High School Charter School Symbol sizes determined by student enrollment number Sources: NYC DOE & NYC DOE School Portal Websites CHA CODE SCHOOL NAME RTE SCHOOL GRADES ENROLLM ADDRESS R TYPE ENT M089 P.S. 89 Elementary PK,0K,01,02,03,04,05,SE 464 201 WARREN STREET Middle M289 I.S. 289 School 06,07,08,SE 290 201 WARREN STREET M150 P.S. 150 Elementary PK,0K,01,02,03,04,05 181 334 GREENWICH STREET P.S. 234 INDEPENDENCE M234 SCHOOL Elementary 0K,01,02,03,04,05,SE 779 292 GREENWICH STREET M418 MILLENNIUM HIGH SCHOOL High school 09,10,11,12,SE 617 75 BROAD STREET LEADERSHIP AND PUBLIC M425 SERVICE HIGH SCHOOL High school 09,10,11,12,SE 673 90 TRINITY PLACE HIGH SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS M489 AND FINANCE High school 09,10,11,12,SE 737 100 TRINITY PLACE M475 STUYVESANT HIGH SCHOOL High school 09,10,11,12 3280 345 CHAMBERS STREET JOHN V.