Tyler Pollard Farm Survey Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

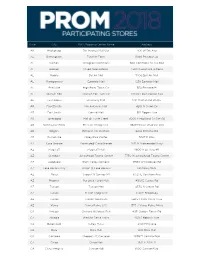

Prom 2018 Event Store List 1.17.18

State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address AK Anchorage 5th Avenue Mall-Sur 406 W 5th Ave AL Birmingham Tutwiler Farm 5060 Pinnacle Sq AL Dothan Wiregrass Commons 900 Commons Dr Ste 900 AL Hoover Riverchase Galleria 2300 Riverchase Galleria AL Mobile Bel Air Mall 3400 Bell Air Mall AL Montgomery Eastdale Mall 1236 Eastdale Mall AL Prattville High Point Town Ctr 550 Pinnacle Pl AL Spanish Fort Spanish Fort Twn Ctr 22500 Town Center Ave AL Tuscaloosa University Mall 1701 Macfarland Blvd E AR Fayetteville Nw Arkansas Mall 4201 N Shiloh Dr AR Fort Smith Central Mall 5111 Rogers Ave AR Jonesboro Mall @ Turtle Creek 3000 E Highland Dr Ste 516 AR North Little Rock Mc Cain Shopg Cntr 3929 Mccain Blvd Ste 500 AR Rogers Pinnacle Hlls Promde 2202 Bellview Rd AR Russellville Valley Park Center 3057 E Main AZ Casa Grande Promnde@ Casa Grande 1041 N Promenade Pkwy AZ Flagstaff Flagstaff Mall 4600 N Us Hwy 89 AZ Glendale Arrowhead Towne Center 7750 W Arrowhead Towne Center AZ Goodyear Palm Valley Cornerst 13333 W Mcdowell Rd AZ Lake Havasu City Shops @ Lake Havasu 5651 Hwy 95 N AZ Mesa Superst'N Springs Ml 6525 E Southern Ave AZ Phoenix Paradise Valley Mall 4510 E Cactus Rd AZ Tucson Tucson Mall 4530 N Oracle Rd AZ Tucson El Con Shpg Cntr 3501 E Broadway AZ Tucson Tucson Spectrum 5265 S Calle Santa Cruz AZ Yuma Yuma Palms S/C 1375 S Yuma Palms Pkwy CA Antioch Orchard @Slatten Rch 4951 Slatten Ranch Rd CA Arcadia Westfld Santa Anita 400 S Baldwin Ave CA Bakersfield Valley Plaza 2501 Ming Ave CA Brea Brea Mall 400 Brea Mall CA Carlsbad Shoppes At Carlsbad -

2017 Scholarship Reception May 11, 2017 at Marvin United Methodist Church Welcome!

East Texas Communities Foundation 2017 Scholarship Reception May 11, 2017 at Marvin United Methodist Church Welcome! East Texas Communities Foundation is pleased to honor the 86 new recipients of scholarships awarded for the 2017-18 academic year. These students were selected from almost 1,400 applicants for 48 different scholarships. Their awards total $122,000. In addition to this evening’s honorees, 32 renewing scholarship recipients will be awarded $73,500 to continue their education. The total amount of scholarship money East Texas Communities Foundation will distribute for the coming school year is $196,400. Our Purpose ETCF works with individuals, families, businesses, financial advisors and nonprofit organizations to create charitable funds which support a wide variety of community causes and individual philanthropic interests. To create your legacy contact ETCF at 903-533-0208 or email [email protected] Our Mission East Texas Communities Foundation supports philanthropy by offering simple ways for donors to achieve their long-term charitable goals. PROGRAM 5:30 Reception 5:45 Welcome Kyle Penney President, East Texas Communities Foundation 5:50 Remarks Doug Bolles Board Chair, East Texas Communities Foundation 5:55 Speaker Barbara Bass, C.P.A. Partner, Gollob Morgan Peddy P.C., former Mayor of Tyler, 2008-2014 6:05 Awards Mary Lynn Smith Program Officer, East Texas Communities Foundation Our Purpose ETCF works with individuals, families, businesses, financial advisors and nonprofit organizations to create charitable funds which support a wide variety of community causes and individual philanthropic interests. To create your legacy contact ETCF at 903-533-0208 or email [email protected] Follow us on Facebook: www.facebook.com/SimplifiedGiving Adam Carroll Scholarship Established in 2002 with gifts from the family and friends of Adam Carroll, this scholarship honors the memory of a young man known for his love of people, his zest for life, and his love of sports. -

Official Rules

OFFICIAL RULES NO PURCHASE OR PAYMENT NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN. A PURCHASE OR PAYMENT WILL NOT INCREASE AN ENTRANT’S CHANCES OF WINNING. OPEN TO LEGAL RESIDENTS OF THE UNITED STATES AND THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA (EXCLUDING FLORIDA, NEW YORK AND RHODE ISLAND) WHO ARE AT LEAST 18 YEARS OF AGE AT THE TIME OF ENTRY. VOID IN FLORIDA, NEW YORK, RHODE ISLAND AND WHERE PROHIBITED OR RESTRICTED BY LAW. To Enter: NO PURCHASE NECESSARY. PURCHASE WILL NOT INCREASE YOUR CHANCES OF WINNING. To be eligible, entrant (“Entrant”) must provide the Administrator (as defined herein) of this promotion (the “Promotion”), Pro Silver Star, Ltd. (the “Administrator”) and J.C. Penney Corporation Inc. (the “Sponsor”), with its full name, email address, phone number, zip code and date of birth. Limit one (1) entry per person. Administrator will not be responsible for entries lost, delayed, incomplete or misdirected. Entries will become the sole property of Administrator and by entering, Entrant expressly consents to adding his/her name to receive future promotional offers, and using Entrant’s name for advertising, publicity or any other purposes whatsoever, as determined by Administrator in its sole discretion, without compensation and with or without attribution to Entrant, as Sponsor and/or Administrator in their sole discretion, without compensation and with Method of Entry: A. Purchase and Online Entry: Entry codes are available with the purchase of one (1) limited edition fleece bearing The Salvation Army and Dallas Cowboys trademarks (the “Fleece”) at select JCPenney stores in Texas as listed in the Appendix of these Official Rules (each a “Participating Store” and collectively the “Participating Stores”), while supplies last. -

2019 Dallas Cowboys Training Camp Promo

Training Camp Store Allocations Store Number Name Address 2685 The Parks Mall 3851 S Cooper St 2795 Stonebriar Mall 2607 Preston Rd 2434 Coronado Center 6600 Menaul Blvd NE Ste 3000 2939 North Star Mall 7400 San Pedro Ave 226 La Plaza 2200 S 10th St 2904 Southpark Meadows S/C 9500 S IH-35 Ste H 631 Ingram Park Mall 6301 NW Loop 410 702 Cielo Vista Mall 8401 Gateway Blvd W 1330 La Palmera Mall 5488 S Padre Island Dr Ste 4000 179 Timber Creek Crossing 6051 Skillman St 2946 Plaza at Rockwall 1015 E I 30 2877 The Rim Shopping Center 17710 La Cantera Pkwy 2338 Town East Mall 6000 Town East Mall 2055 Collin Creek Mall 821 N Central Expwy 1046 Golden Triangle Mall 2201 S Interstate 35 E Ste D 2410 Vista Ridge Mall 2401 S Stemmons Fwy Ste 4000 2884 Tech Ridge Center 12351 N IH-35 2826 Cedar Hill Village 333 N Hwy 67 2960 El Mercado Plaza 1950 Joe Battle Blvd 2969 Sherman Town Center 610 Graham Dr 2934 University Oaks Shopping Center 151 University Oaks 993 South Park Mall 2418 SW Military Dr 2982 Village at Fairview 301 Stacy Rd 2921 Robertsons Creek 5751 Long Prairie Rd 2105 Crossroads Mall 6834 Wesley St Ste C 1943 North East Mall 1101 Melbourne Dr Ste 5000 1419 Ridgmar Mall 1900 Green Oaks Rd 2093 Mesilla Valley Mall 700 Telshor Blvd Ste 2000 2021 Richland Mall 6001 W Waco Dr 579 Music City Mall 4101 E 42nd St 485 Mall of Abilene 4310 Buffalo Gap Rd 2682 Penn Square Mall 1901 NW Expwy Ste 1200 2833 Rolling Oaks Mall 6909 N Loop 1604 E 2806 Sunrise Mall 2370 N Expwy Ste 2000 712 Sikes Senter Mall 3111 Midwestern Pkwy 996 Broadway Square Mall 4401 S Broadway 450 Rio West Mall 1300 W Maloney Ave Ste A 1749 Central Mall 2400 Richmond Rd Ste 61 2905 Alliance Town Center 3001 Texas Sage Trl 658 Mall De Norte S/C 5300 San Dario 1989 Sunset Mall 6000 Sunset Mall 259 Colonial/Temple Mall 3111 S 31st St Ste 3301 1101 Valley Crossing Shopping Center 715 E Expressway 83 2036 Midland Park Mall 4511 N Midkiff Rd 304 Longview Mall 3550 McCann Rd 2110 Killeen Mall 2100 S W.S. -

April, 1992 • ISSN 0897-4314 Efteia Two on Sportsmanship

EBguer State Meet one-act play schedule School productions a great bargain MAY 7, THURSDAY (Note: PAC - Performing Arts Center) 7:30 am — AAA company meet ing and rehearsals: Concert Hall, south entrance of the PAC. 4:00 pm — AAA contest, four plays: Bass Concert Hall. 7:30 pm — AAA contest, four plays: Bass Concert Hall. MAY 8, FRIDAY 7:30 am — AA company meeting and rehearsals: McCullough Theatre, northeast corner of the PAC AAAA company meeting and re hearsals: Bass Concert Hall, south en trance of the PAC. 9:00 am — 12:00 noon Conference AAA critiques: Bass Concert Hall, Lobby Level. 4:00 pm — AA contest, four plays: •McCullough Theatre. AAAA contest, four plays: Bass Concert Hall. 7:30 pm—AA contest, four plays: 'McCullough Theatre. The FIRST time is the charm AAAA contest, four plays: Bass Concert Hall. Longview, San Marcos claim 5A titles in initial appearances MAY 9, SATURDAY 7:30 am — A company meeting BY PETER CONTRERAS SOC it to 'em. Members of the Dallas and rehearsals: McCullough Theatre, Director of Public Information South Oak Cliff team (above) celebrate their northeast corner of the PAC. state 4A finals win over Georgetown. (Left) AAAAA company meeting and A pair of first-time players, Longview in the Duncanville's Lana Tucker drives in the rehearsals: Bass Concert Hall, south boy's tournament and San Marcos in the girl's Pantherette's loss to San Marcos in the 5A girls championship game. entrance of the PAC. tournament, handled the pressure of participating Photos by Joey Lin. 9:00 am —12:00 in the UIL State Basketball Championships without any problem in claiming class 5A state noon Conference AA and AAAA cri join the football title won in December. -

The Building of an East Texas Barrio: a Brief Overview of the Creation of a Mexican American Community in Northeast Tyler

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 47 Issue 2 Article 9 10-2009 The Building of an East Texas Barrio: A Brief Overview of the Creation of a Mexican American Community in Northeast Tyler Alexander Mendoza Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Mendoza, Alexander (2009) "The Building of an East Texas Barrio: A Brief Overview of the Creation of a Mexican American Community in Northeast Tyler," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 47 : Iss. 2 , Article 9. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol47/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 26 EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION THE BUILDING OF AN EAST TEXAS BARRIO: A BRIEF OVERVIE\\' OF THE CREATION OF A MEXICAN AMERICAN COMl\1UNITY IN NORTHEAST TYLER* By Alexander Mendoza In September of 1977, lose Lopez, an employee at a Tyler meatpacking plant. and Humberto Alvarez, a "jack of all trades" who worked in plumbing, carpentry, and electricity loaded up their children and took them to local pub lic schools to enroll them for the new year. On that first day of school, how ever, Tyler Independent School District (TISD) officials would not allow the Lopez or Alvarez children to enroll. Tn July, TISD trustees had voted to charge 51.000 tuition to the children of illegal immigrants. -

Store # State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address Date

Store # State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address Date 2918 AL ALABASTER COLONIAL PROMENADE 340 S COLONIAL DR Now Open! 2218 AL HOOVER RIVERCHASE GALLERIA 2300 RIVERCHASE GALLERIA Now Open! 219 AL MOBILE BEL AIR MALL MOBILE, AL 36606-3411 Now Open! 2840 AL MONTGOMERY EASTDALE MALL MONTGOMERY, AL 36117-2154 Now Open! 2956 AL PRATTVILLE HIGH POINT TOWN CENTER PRATTVILLE, AL 36066-6542 Now Open! 2875 AL SPANISH FORT SPANISH FORT TOWN CENTER 22500 TOWN CENTER AVE Now Open! 2869 AL TRUSSVILLE TUTWILER FARM 5060 PINNACLE SQ Now Open! 2709 AR FAYETTEVILLE NW ARKANSAS MALL 4201 N SHILOH DR Now Open! 1961 AR FORT SMITH CENTRAL MALL 5111 ROGERS AVE Now Open! 2914 AR LITTLE ROCK SHACKLEFORD CROSSING 2600 S SHACKLEFORD RD Now Open! 663 AR NORTH LITTLE ROCK MCCAIN SHOPPING CENTER 3929 MCCAIN BLVD STE 500 Now Open! 2879 AR ROGERS PINNACLE HLLS PROMDE 2202 BELLVIEW RD Now Open! 2936 AZ CASA GRANDE PROMNDE AT CASA GRANDE 1041 N PROMENADE PKWY Now Open! 157 AZ CHANDLER MILL CROSSING 2180 S GILBERT RD Now Open! 251 AZ GLENDALE ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER 7750 W ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER Now Open! 2842 AZ GOODYEAR PALM VALLEY CORNERST 13333 W MCDOWELL RD Now Open! 2940 AZ LAKE HAVASU CITY SHOPS AT LAKE HAVASU 5651 HWY 95 N Now Open! 2419 AZ MESA SUPERSTITION SPRINGS MALL 6525 E SOUTHERN AVE Now Open! 2846 AZ PHOENIX AHWATUKEE FOOTHILLS 5050 E RAY RD Now Open! 1480 AZ PHOENIX PARADISE VALLEY MALL 4510 E CACTUS RD Now Open! 2902 AZ TEMPE TEMPE MARKETPLACE 1900 E RIO SALADO PKWY STE 140 Now Open! 1130 AZ TUCSON EL CON SHOPPING CENTER 3501 E BROADWAY Now Open! 90 -

HUGHES SPRINGS ISD Check Register (2015-2016)

HUGHES SPRINGS ISD Check Register (2015-2016) Check # Date Vendor Description Amount 22782 9/3/2015 American Express Annual Membership Fee 118.32 22783 9/3/2015 Capital One N.A. Travel - FCSTAT Conference 622.06 9/3/2015 Capital One N.A. Meals - Coaches Retreat 740.46 9/3/2015 Capital One N.A. Meals 73.34 9/3/2015 Capital One N.A. Cleaning Supplies 33.85 9/3/2015 Capital One N.A. Meals 75.70 9/3/2015 Capital One N.A. Dummies for Sled 1,477.00 9/3/2015 Capital One N.A. Meals - Coaches (7/30) 106.84 9/3/2015 Capital One N.A. Meals - Coaches (8/8) 50.72 9/3/2015 Capital One N.A. Meals/Travel - Kemah Reading Academy 141.57 9/3/2015 Capital One N.A. License for High School Robotics Class 299.00 9/3/2015 Capital One N.A. Software License for Robotics 399.95 9/3/2015 Capital One N.A. Outdoor Adventure/Wildlife Curriculum 1,000.00 9/3/2015 Capital One N.A. Supplies for CTB 2,095.98 9/3/2015 Capital One N.A. Meals/Fuel - State Dyslexia Conference 299.41 9/3/2015 Capital One N.A. Hotel - State Dyslexia Conference 357.00 9/3/2015 Capital One N.A. Food for New Teacher Orientation 287.84 9/3/2015 Capital One N.A. Life Skills Supplies 493.31 9/3/2015 Capital One N.A. Supplies for Superintendent Retirement 24.26 9/3/2015 Capital One N.A. -

19980019140.Pdf

207050 The preparation of Education and Training Report: Performance Report--FY 1997 was managed by Mary Anne Stoutsenberger, University Program Specialist, under the overall direction of Bettie White, Director of the Minority University Research and Education Division (MURED), with text editing, layout design, and graphs provided by Jonathan L. Friedman, Vanessa Nugent, and Jim Hadow, respectively, at Headquarters Printing and Design. The Allied Technology Group, Inc., of Rockville, Maryland, under the direction of Ms. Clare Hines, compiled and analyzed the data presented in this report. Allied staff members who worked on this report were Dr. AIford H. Ottley, Ms. Rachel Smith, and Ms. Lauren Buchheister. Any questions or comments concerning this document should be submitted to: NASA Headquarters Office of Equal Opportunity Programs MURED, Code EU Washington, DC 20546 http://mured.gsfc.nasa.gov OneofthegoalsofthisNationisthatitsstudentsattaina levelof scientificliteracythatwill enablethemtofunctionwellin atech- nologicalsociety.Scienceandtechnologyarecentralelementsof NASAprogramsandlie attheheartof achievingtheNASAvision andmission.NASAscienceandtechnologyhaveprovidedpublic inspiration,revealednewworlds,disclosedsecretsof theuni- verse,providedvitalinsightsintoEarth'senvironment,helped shapethedevelopmentof atmosphericflight,andyieldedinfor- mationthathasimprovedlifeonEarth.Inshort,NASAscienceis aninvestmentin America'sfuture. EvenmoreinspirationalisthefactthatNASAscienceandtech- nologyaresystematicallypenetratingeveryaspectoftheeduca- -

East Texas Communities Foundation 2016 Scholarship Reception May 12, 2016 at Marvin United Methodist Church Welcome!

East Texas Communities Foundation 2016 Scholarship Reception May 12, 2016 at Marvin United Methodist Church Welcome! East Texas Communities Foundation is pleased to honor the 79 new recipients of scholarships awarded for the 2016-17 academic year. These students were selected from almost 1,200 applicants for 41 dierent scholarships. Their awards total $104,550. In addition to this evening’s honorees, 33 renewing scholarship recipients will be awarded $76,250 to continue their education. The total amount of scholarship money East Texas Communities Foundation will distribute for the coming school year is $180,800. Our Purpose ETCF works with individuals, families, businesses, financial advisors and nonprofit organizations to create charitable funds which support a wide variety of community causes and individual philanthropic interests. To create your legacy contact ETCF at 903-533-0208 or email [email protected] Our Mission East Texas Communities Foundation supports philanthropy by offering simple ways for donors to achieve their long-term charitable goals. PROGRAM 5:30 Reception 5:45 Welcome Kyle Penney President, East Texas Communities Foundation 5:50 Remarks Gordon Northcutt Board President, East Texas Communities Foundation 5:55 Speaker Lorri Allen Journalist, Author and Speaker 6:05 Awards Mary Lynn Smith Program Ocer, East Texas Communities Foundation Our Purpose ETCF works with individuals, families, businesses, financial advisors and nonprofit organizations to create charitable funds which support a wide variety of community causes and individual philanthropic interests. To create your legacy contact ETCF at 903-533-0208 or email [email protected] Follow us on Facebook: www.facebook.com/SimplifiedGiving Adam Carroll Scholarship Established in 2002 with gifts from the family and friends of Adam Carroll, this scholarship honors the memory of a young man known for his love of people, his zest for life, and his love of sports. -

City of Tyler Parks & Open Space Master Plan

CITY OF TYLER, TEXAS PARKS, RECREATION & OPEN SPACE MASTER PLAN 2010 - 2020 Table of Contents I. Introduction. P .age 2 II. Goals & Objectives. P.age 6 III. Methodology. P.age 7 IV. Park Classification & Inventory.. P.age 8 V. Level of Service. Page 17 VI. Assessment of Needs and Conclusions.. Page 19 VII. Priorities and Recommendations. Page 35 VIII. Implementation Schedule. Page 39 IX. Existing & Available Mechanisms. Page 44 X. Summary.. Page 46 Appendix I. Citizen Survey Results II. Public Meeting Input I. INTRODUCTION In July of 2009, the City of Tyler commissioned MHS Planning and Design, LLC to assist in developing a new Parks and Open Space Master Plan. This plan is a more detailed follow-up to the 2007 “City of Tyler Comprehensive Plan - Tyler 21.” The 2010 Parks and Open Space Master Plan is intended to: • Provide the City of Tyler with an information base to help guide decisions related to parks, recreation and open space • Assist in the implementation of those decisions and set guidelines for future park and open space development • Provide feasible recommendations to the governmental body and be in accordance with the desires of Tyler’s residents • Include all land within the City of Tyler • Provide detailed parks and open space project recommendations through 2020 • Provide general parks and open space recommendations through 2040 • Provide emphasis and detailed cost projections for projects recommended for implementation City of Tyler Parks & Open Space Master Plan 2010-2020 Page |2 The following pages of the Master Plan -

CWA District 6

DISTRICT 6 July 20, 2020 TO: AT&T Mobility Local Presidents FROM: Sylvia J. Ramos, Assistant to the Vice President SUBJECT: AT&T "At Your Service" - Retail Launch this Week The District received an email notice today from the Company announcing the Retail "Our Promise" is being replaced by AT&T “At Your Service”. The Company stated employees will start to see information beginning today and through the week. Please contact your assigned CWA Representative with any questions. SJR/sv opeiu#13 AT&T "At Your Service" Launch Overview c: Claude Cummings, Jr. District 6 Administrative Staff District 6 CWA Representatives AT&T At Your Service Retail Launch Overview July 2020 At Your Service/ July, 2020 / © 2020 AT&T Intellectual Property - AT&T Proprietary (Internal Use Only) 1 AT YOUR SERVICE OVERVIEW At Your Service delivers on what customers tell us they want. Keeping them and our employees safe with important precautions and touchless experiences. Expert assistance in the fundamentals like billing solutions and content transfers. Taking ownership of their needs and providing personalized solutions. Demonstrating genuine appreciation with our Signature Acts of Appreciation. All done with courtesy and kindness, from beginning to end. We are going to win in the marketplace. And we’re going to do it by leading with outstanding service. AT YOUR SERVICE OVERVIEW 1 HIGHLIGHT CUSTOMER & EMPLOYEE SAFETY • Talk about what AT&T has done to make customers feel comfortable returning to our stores: Masks, Health Screening App, Social Distancing, etc. 2 RECOMMEND TOUCHLESS SOLUTIONS • Educate customers on our new options, from curbside, in-home delivery, or digital.