Master Reference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visual Novel Game Critical Hit Free Download Top 15 Best Visual Novels of All Time on PC & Steam

visual novel game critical hit free download Top 15 Best Visual Novels of All Time on PC & Steam. From mind-blowing twists to heartwarming stories, we’ve got you covered. Home » Galleries » Features » Top 15 Best Visual Novels of All Time on PC & Steam. Visual Novels are one of the oldest genres around for gaming. As such, there’s been a ton of them. While they’ve largely kept to PC, they do sometimes dive into the console world. But there’s no denying that the best visual novels can be found on PC and – more specifically – Steam. Here they are, hand-picked by us for you. Here are the best visual novels of all time, available for you to download on PC and steam. Best Visual Novels on PC and Steam. Umineko (When They Cry) – Umineko is a visual novel in the truest sense of the term. Meaning there’s no gameplay to speak of at all; the entire ‘game’ is just a matter of clicking through copious amounts of text and watching as the story unfold. Despite the sluggish start to the first three episodes, things pick up dramatically once the creepy stuff kicks in, and Umineko stands tall as one of the most intriguing and engaging visual novel stories we’ve ever played. That soundtrack too, though. Best Visual Novels on PC and Steam. Higurashi (When They Cry) – Higurashi is a predecessor of sorts to Umineko, and while its story is just as gripping, we don’t recommend starting with this one unless you enjoyed what you saw of Umineko. -

In- and Out-Of-Character

Florida State University Libraries 2016 In- and Out-of-Character: The Digital Literacy Practices and Emergent Information Worlds of Active Role-Players in a New Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game Jonathan Michael Hollister Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION & INFORMATION IN- AND OUT-OF-CHARACTER: THE DIGITAL LITERACY PRACTICES AND EMERGENT INFORMATION WORLDS OF ACTIVE ROLE-PLAYERS IN A NEW MASSIVELY MULTIPLAYER ONLINE ROLE-PLAYING GAME By JONATHAN M. HOLLISTER A Dissertation submitted to the School of Information in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 Jonathan M. Hollister defended this dissertation on March 28, 2016. The members of the supervisory committee were: Don Latham Professor Directing Dissertation Vanessa Dennen University Representative Gary Burnett Committee Member Shuyuan Mary Ho Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Grandpa Robert and Grandma Aggie. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to my committee, for their infinite wisdom, sense of humor, and patience. Don has my eternal gratitude for being the best dissertation committee chair, mentor, and co- author out there—thank you for being my friend, too. Thanks to Shuyuan and Vanessa for their moral support and encouragement. I could not have asked for a better group of scholars (and people) to be on my committee. Thanks to the other members of 3 J’s and a G, Julia and Gary, for many great discussions about theory over many delectable beers. -

Release Notes for Fedora 15

Fedora 15 Release Notes Release Notes for Fedora 15 Edited by The Fedora Docs Team Copyright © 2011 Red Hat, Inc. and others. The text of and illustrations in this document are licensed by Red Hat under a Creative Commons Attribution–Share Alike 3.0 Unported license ("CC-BY-SA"). An explanation of CC-BY-SA is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/. The original authors of this document, and Red Hat, designate the Fedora Project as the "Attribution Party" for purposes of CC-BY-SA. In accordance with CC-BY-SA, if you distribute this document or an adaptation of it, you must provide the URL for the original version. Red Hat, as the licensor of this document, waives the right to enforce, and agrees not to assert, Section 4d of CC-BY-SA to the fullest extent permitted by applicable law. Red Hat, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, the Shadowman logo, JBoss, MetaMatrix, Fedora, the Infinity Logo, and RHCE are trademarks of Red Hat, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries. For guidelines on the permitted uses of the Fedora trademarks, refer to https:// fedoraproject.org/wiki/Legal:Trademark_guidelines. Linux® is the registered trademark of Linus Torvalds in the United States and other countries. Java® is a registered trademark of Oracle and/or its affiliates. XFS® is a trademark of Silicon Graphics International Corp. or its subsidiaries in the United States and/or other countries. MySQL® is a registered trademark of MySQL AB in the United States, the European Union and other countries. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Gaming Introduction/Schedule ...........................................4 Role Playing Games (Campaign) ........................................25 Board Gaming ......................................................................7 Campaign RPGs Grid ..........................................................48 Collectible Card Games (CCG) .............................................9 Role Playing Games (Non-Campaign) ................................35 LAN Gaming (LAN) .............................................................18 Non-Campaign RPGs Grid ..................................................50 Live Action Role Playing (LARP) .........................................19 Table Top Gaming (GAME) .................................................52 NDMG/War College (NDM) ...............................................55 Video Game Programming (VGT) ......................................57 Miniatures .........................................................................20 Maps ..................................................................................61 LOCATIONS Gaming Registration (And Help!) ..................................................................... AmericasMart Building 1, 2nd Floor, South Hall Artemis Spaceship Bridge Simulator ..........................................................................................Westin, 14th Floor, Ansley 7/8 Board Games ................................................................................................... AmericasMart Building 1, 2nd -

Freecol Documentation, User Guide for Version V0.11.6

FreeCol Documentation User Guide for Version v0.11.6 The FreeCol Team December 30, 2019 2 Contents 1 Introduction7 1.1 About FreeCol..........................7 1.2 The Original Colonization....................7 1.3 About this manual........................9 1.3.1 Differences between the rule sets.............9 1.4 Liberty and Immigration..................... 11 2 Installation 13 2.1 System Requirements....................... 13 2.1.1 FreeCol on Windows................... 14 2.2 Compiling FreeCol........................ 14 3 Interface 15 3.1 Starting the game......................... 15 3.1.1 Command line options.................. 15 3.1.2 Game setup........................ 19 3.1.3 Map Generator Options................. 21 3.1.4 Game Options....................... 22 3.2 Client Options........................... 25 3.2.1 Display Options...................... 25 3.2.2 Translations........................ 26 3.2.3 Message Options..................... 27 3.2.4 Audio Options...................... 28 3.2.5 Savegame Options.................... 29 3.2.6 Warehouse Options.................... 29 3.2.7 Keyboard Accelerators.................. 29 3.2.8 Other Options....................... 29 3.3 The main screen.......................... 30 3 4 CONTENTS 3.3.1 The Menubar....................... 31 3.3.2 The Info Panel...................... 36 3.3.3 The Minimap....................... 36 3.3.4 The Unit Buttons..................... 36 3.3.5 The Compass Rose.................... 37 3.3.6 The Main Map...................... 37 3.4 The Europe Panel......................... 42 3.5 The Colony panel......................... 43 3.5.1 The Warehouse Dialog.................. 46 3.5.2 The Build Queue Panel.................. 46 3.6 Customization........................... 47 4 The New World 49 4.1 Terrain Types........................... 49 4.2 Goods............................... 50 4.2.1 Trade Routes....................... 52 4.3 Special Resources........................ -

" Get a Free Item Pack with Every Activation!"--Do Incentives Increase the Adoption Rates of Two-Factor Authentication?

... ...; aop ... Karoline Busse*, Sabrina Amft, Daniel Hecker, and Emanuel von Zezschwitz “Get a Free Item Pack with Every Activation!” Do Incentives Increase the Adoption Rates of Two-Factor Authentication? https://doi.org/..., Received ...; accepted ... Abstract: Account security is an ongoing issue in practice. Two-Factor Authen- tication (2FA) is a mechanism which could help mitigate this problem, however adoption is not very high in most domains. Online gaming has adopted an in- teresting approach to drive adoption: Games offer small rewards such as visual modifications to the player’s avatar’s appearance, if players utilize 2FA. Inthis paper, we evaluate the effectiveness of these incentives and investigate how they can be applied to non-gaming contexts. We conducted two surveys, one recruiting gamers and one recruiting from a general population. In addition, we conducted three focus group interviews to evaluate various incentive designs for both, the gaming context and the non-gaming context. We found that visual modifications, which are the most popular type of gaming-related incentives, are not as popular in non-gaming contexts. However, our design explorations indicate that well-chosen incentives have the potential to lead to more users adopting 2FA, even outside of arXiv:1910.07269v1 [cs.CR] 16 Oct 2019 the gaming context. Keywords: Two-Factor Authentication, Incentives, Gamification, Usable Security, Authentication, User Research PACS: ... Communicated by: ... Dedicated to ... *Corresponding author: Karoline Busse, Daniel Hecker, University of Bonn Sabrina Amft, Leibniz University Hannover Emanuel von Zezschwitz, University of Bonn & Fraunhofer FKIE 2 Busse, Amft, Hecker, von Zezschwitz (a) (b) Fig. 1: Examples of incentives for adopting 2FA. -

Modularity Index Metrics for Java-Based Open Source Software Projects

(IJACSA) International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, Vol. 2, No. 11, 2011 Modularity Index Metrics for Java-Based Open Source Software Projects Andi Wahju Rahardjo Emanuel Retantyo Wardoyo, Jazi Eko Istiyanto, Informatics Bachelor Program, Khabib Mustofa Faculty of Information Technology, Dept. of Computer Science and Electronics, Maranatha Christian University, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Bandung, Indonesia Yogyakarta, Indonesia Abstract — Open Source Software (OSS) Projects are gaining contributing to such unfruitful result such as no formal means popularity these days, and they become alternatives in building i.e. no project planning [4], poor coding styles of project software system. Despite many failures in these projects, there initiators [13] and poor architectural design [12]. We believe are some success stories with one of the identified success factors that some new approaches with respect to modularity to is modularity. This paper presents the first quantitative software counter such problems in OSS Projects are needed. Until now, metrics to measure modularity level of Java-based OSS Projects modularity has been identified as a key success factor of OSS called Modularity Index. This software metrics is formulated by projects, but how to apply modularity, especially from early analyzing modularity traits such as size, complexity, cohesion, phase of the project is not yet understood. and coupling of 59 Java-based OSS Projects from sourceforge.net using SONAR tool. These OSS Projects are selected since they This paper presents the formulation of Modularity Index have been downloaded more than 100K times and believed to which is the first quantitative software metrics to measure the have the required modularity trait to be successful. -

Mukokuseki and the Narrative Mechanics in Japanese Games

Mukokuseki and the Narrative Mechanics in Japanese Games Hiloko Kato and René Bauer “In fact the whole of Japan is a pure invention. There is no such country, there are no such peo- ple.”1 “I do realize there’s a cultural difference be- tween what Japanese people think and what the rest of the world thinks.”2 “I just want the same damn game Japan gets to play, translated into English!”3 Space Invaders, Frogger, Pac-Man, Super Mario Bros., Final Fantasy, Street Fighter, Sonic The Hedgehog, Pokémon, Harvest Moon, Resident Evil, Silent Hill, Metal Gear Solid, Zelda, Katamari, Okami, Hatoful Boyfriend, Dark Souls, The Last Guardian, Sekiro. As this very small collection shows, Japanese arcade and video games cover the whole range of possible design and gameplay styles and define a unique way of narrating stories. Many titles are very successful and renowned, but even though they are an integral part of Western gaming culture, they still retain a certain otherness. This article explores the uniqueness of video games made in Japan in terms of their narrative mechanics. For this purpose, we will draw on a strategy which defines Japanese culture: mukokuseki (borderless, without a nation) is a concept that can be interpreted either as Japanese commod- ities erasing all cultural characteristics (“Mario does not invoke the image of Ja- 1 Wilde (2007 [1891]: 493). 2 Takahashi Tetsuya (Monolith Soft CEO) in Schreier (2017). 3 Funtime Happysnacks in Brian (@NE_Brian) (2017), our emphasis. 114 | Hiloko Kato and René Bauer pan” [Iwabuchi 2002: 94])4, or as a special way of mixing together elements of cultural origins, creating something that is new, but also hybrid and even ambig- uous. -

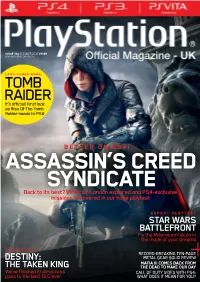

Official Playstation Magazine! Get Your Copy of the Game We Called A, “Return to Form for the Legendary Spookster,” in OPM #108 When You Subscribe

ISSUE 114 OCTOBER 2015 £5.99 gamesradar.com/opm LARA COMES HOME TOMB RAIDER It’s official! First look as Rise Of The Tomb Raider heads to PS4 ASSASSIN’SBETTER ON PS4! CREED SYNDICATE Back to its best? Victorian London explored and PS4-exclusive missions uncovered in our huge playtest EXPERT PLAYTEST STAR WARS BATTLEFRONT Fly the Millennium Falcon in the mode of your dreams COMPLETED! RECORD-BREAKING TEN-PAGE METAL GEAR SOLID REVIEW DESTINY: MAFIA III COMES BACK FROM THE TAKEN KING THE DEAD TO MAKE OUR DAY We’ve finished it! All-access CALL OF DUTY SIDES WITH PS4: pass to the best DLC ever WHAT DOES IT MEAN FOR YOU? ISSUE 114 / OCT 2015 Future Publishing Ltd, Quay House, The Ambury, Welcome Bath BA1 1UA, United Kingdom Tel +44 (0) 1225 442244 Fax: +44 (0) 1225 732275 here’s just no stopping the PS4 train. Email [email protected] Twitter @OPM_UK Web www.gamesradar.com/opm With Sony’s super-machine on track to EDITORIAL Editor Matthew Pellett @Pelloki eventually overtake PS2 as the best- Managing Art Editor Milford Coppock @milfcoppock T Production Editor Dom Reseigh-Lincoln @furianreseigh selling console ever, developers keep News Editor Dave Meikleham flocking to Team PlayStation. This month we CONTRIBUTORS Words Alice Bell, Jenny Baker, Ben Borthwick, Matthew Clapham, Ian Dransfield, Matthew Elliott, Edwin Evans-Thirlwell, go behind the scenes of five of the best Matthew Gilman, Ben Griffin, Dave Houghton, Phil Iwaniuk, Jordan Farley, Louis Pattison, Paul Randall, Jem Roberts, Sam games due out this year to show you why Roberts, Tom Sykes, Justin Towell, Ben Wilson, Iain Wilson Design Andrew Leung, Rob Speed the biggest blockbusters of the gaming ADVERTISING world are set to be better on PS4. -

The Information Worlds of Online Role-Players* 온라인 롤 플레이어의 정보 세계

The Information Worlds of Online Role-Players* 온라인 롤 플레이어의 정보 세계 Jonathan M. Hollister (홀리스터 조나단)** ABSTRACT Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games (MMORPGs) are played by millions of people around the world. Within MMORPGs, players explore, solve mysteries, craft items, battle against dungeon or raid bosses, or compete against other players, all while using a variety of information and information behaviors. Role-players in MMORPGs develop identities and engage in interactive storytelling with other role-players as their characters. An ethnographic approach combining overt participant observation and engagement, semi-structured interviews, and artifact collection was used to explore and describe the social information behaviors of role-players through the lens of the theory of information worlds. The social types evident in the role-playing community in WildStar, a science fantasy-themed MMORPG, are closely interrelated to and differentiated by social norms and information values that dictate acceptable characters, stories, character actions, and appropriate lore sources as well as how to role-play without violating the boundary between in- and out-of-character information worlds. Role-players maintained the in-character and out-of-character boundary using a set of specific information behaviors to enable engaging and immersive role-playing experiences. Implications of the findings for the theory of information worlds as well as potential applications of role-playing and MMORPGs are also discussed. 초 록 전세계 수백만 명의 이용자가 대규모 멀티 플레이어 온라인 롤 플레잉 게임(MMORPG: Massive Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games)을 즐긴다. MMORPG 내에서 롤 플레이어(역할 참여자)는 다양한 정보사용과 정보행동에 가담하면 서 게임을 탐색하고, 미스터리를 해결하거나, 게임 속 아이템을 만들거나, 괴물이나 보스와의 전투에 참여하며 다른 플레이어 와 경쟁하거나 협력한다. -

Amd A10 7700K

SOUTH AFRICA’S LEADING GAMING, COMPUTER & TECHNOLOGY MAGAZINE APRIL 2014 WIN A PC / PLAYSTATIPLAYSTATIONONON / XBOXXBBOX / NINTENDONININTN ENNDODO / LLIFESTYLEIIFFEESSTYTYLELE PS4 EIGHT REVIEWS INCLUDING Castlevania: Lords of Shadow 2 Final Fantasy XIII: Lightning Returns Plants vs. Zombies: Garden Warfare Thief IT’S CLASSIC! IT’S MODERN! COULD THIS BE EVERYTHING WE WANT IN AN FPS? PUBLISHER Michael “RedTide“ James [email protected] CONTENTS EDITOR Geoff “GeometriX“ Burrows geoff @nag.co.za ART DIRECTOR Chris “SAVAGE“ Savides STAFF WRITERS Dane “Barkskin “ Remendes Tarryn “Azimuth “ van der Byl REGULARS CONTRIBUTING EDITOR Lauren “Guardi3n “ Das Neves 8 Ed's Note 10 Inbox TECHNICAL WRITER Neo “ShockG“ Sibeko 14 Bytes 26 home_coded INTERNATIONAL 74 Mosh Pit CORRESPONDENT Miktar “Miktar” Dracon CONTRIBUTORS OPINION Rodain “Nandrew” Joubert Miklós “Mikit0707 “ Szecsei 14 Miktar’s Meanderingserings Pippa “UnexpectedGirl” Tshabalala 16 I, Gamer Delano “Delano” Cuzzucoli Matt “Sand_Storm” Fick 18 The Game Stalkerer 56 Hardwired FEATURES PHOTOGRAPHY 82 Game Over Chris “SAVAGE“ Savides 36 WOLFENSTEIN: THE NEW Dreamstime.com Fotolia.com ORDER. MEIN LEBEN! PREVIEWS “There ain’t no school like the old SALES EXECUTIVE school.” That’s how it goes, right? Cheryl “Cleona“ Harris 32 The Elder Scrolls Online Or did we just fail hard at being [email protected] 34 WildStar youthful and hippity-hopping? +27 72 322 9875 Does it even matter? Either way, MARKETING AND Wolfenstein: The New Order PROMOTIONS MANAGER REVIEWS eagerly partakes of the old school Jacqui “Jax” Jacobs of fi rst-person shooter-ising. [email protected] 44 Reviews: Introduction And boy, does it look positively +27 82 778 8439 44 Mini review: Fable: scrumptious. -

Mall För Examensarbete

nrik v He d a apa l sk Ma “WHAT IS YOUR DPS, HERO?” Ludonarrative dissonance and player perception of story and mechanics in MMORPGs. Master Degree Project in Informatics One year Level 30 ECTS Spring term 2016 Athanasios Karavatos Supervisor: Björn Berg Marklund Examiner: Mikael Johannesson 1 Abstract This thesis studies the MMORPGs and the ludonarrative dissonance that exist in the complexity of their design. Given the massive multiplayer nature of these games, players of different ambitions and gameplay preference need to coexist, which is a massive challenge for both the players themselves and the designers of these worlds. The balance of these two major aspects of the game, what affects the players and this tension, is the focal point of this thesis. By conducting a survey through various MMORPG player bases, this thesis concludes that this tension is not only a balance between narrative and mechanics but of other aspect as well. These aspects, intertextuality and community, this thesis argues, are the extra aspects that are tight connected with the balancing of narrative and mechanics in a MMORPG and the creation of these complex games and world. All these aspects are affected by the design decisions and affecting of how the players perceive the game world. Keywords: MMORPG, Narrative, Ludonarrative Dissonance, Design. 2 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 2 Background .......................................................................................................