Cory Doctorow Discusses "Radicalized"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk at the Turn of the Twenty-first Century Carlen Lavigne McGill University, Montréal Department of Art History and Communication Studies February 2008 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies © Carlen Lavigne 2008 2 Abstract This study analyzes works of cyberpunk literature written between 1981 and 2005, and positions women’s cyberpunk as part of a larger cultural discussion of feminist issues. It traces the origins of the genre, reviews critical reactions, and subsequently outlines the ways in which women’s cyberpunk altered genre conventions in order to advance specifically feminist points of view. Novels are examined within their historical contexts; their content is compared to broader trends and controversies within contemporary feminism, and their themes are revealed to be visible reflections of feminist discourse at the end of the twentieth century. The study will ultimately make a case for the treatment of feminist cyberpunk as a unique vehicle for the examination of contemporary women’s issues, and for the analysis of feminist science fiction as a complex source of political ideas. Cette étude fait l’analyse d’ouvrages de littérature cyberpunk écrits entre 1981 et 2005, et situe la littérature féminine cyberpunk dans le contexte d’une discussion culturelle plus vaste des questions féministes. Elle établit les origines du genre, analyse les réactions culturelles et, par la suite, donne un aperçu des différentes manières dont la littérature féminine cyberpunk a transformé les usages du genre afin de promouvoir en particulier le point de vue féministe. -

On Books for Young Adults

viewpoint on books for young adults vol 19 no 1 autumn 2011 01.04.2011 Michael Grant’s GONE series continues… PLAGUE - VIEWPOINT cover.indd 1 8/2/11 3:51:11 PM Viewpoint on books for young adults in this issue... Feature Reviews Of Thee I Sing: A Letter to My Daughters by Barack Obama Mike Shuttleworth 2 Luke and the Fire of Life by Salman Rushdie Stella Lees 3 Poetry and Childhood edited by Morag Styles, Louise Joy & David Whitley Sarah Mayor Cox 4 The Maze Runner by James Dashner Bill Wootton 5 iBoy by Kevin Brooks Bill Wootton 6 All Along the Watchtower by Michael Hyde Margaret Kett 7 Haunted by Barbara Haworth-Attard & Virals by Kathy Reichs Liz Derouet 8 For the Win by Cory Doctorow Bec Kavanagh 9 Fear: 13 stories of horror and suspense by RL Stine & Zombies vs Unicorns edited by Justine Larbalestier & Holly Black Susan La Marca 10 Writers on Writing Christina’s Matilda: A waltz of discovery Edel Wignell 11 Other times, Other places: Fictionalising History Goldie Alexander 12 Feature Articles ‘Unless Someone Like You Cares a Whole Awful Lot’: Environmental Picture Books Virginia Lowe 14 Humour, Life, Love, Sadness and Joy: Four novels by Jenny Valentine Pamela Horsey 16 Angela Savage: The Half-Child Clare Kennedy 17 Pinerolo: The Children’s Book Cottage, NSW Jeff Prentice 18 Islands of Discontent Beth Montgomery 19 Vale Ruth Park, 97-200 Stella Lees 20 Eva Ibbotson, 925-200 Ruth Starke 2 Feature Articles Interacting Between Scenes: Nicki Greenberg’s Hamlet Bernard Caleo 22 Misunderstandings & Miscommunications Rae Mariz 23 The Unidentified -

Space and the Re-Purposing of Materials and Technology in William Gibson's Neuromancer and Virtual Light Submitted by Grigori

Space and the Re-Purposing of Materials and Technology in William Gibson’s Neuromancer and Virtual Light Submitted by Grigorios Iliopoulos A thesis submitted to the Department of American Literature and Culture, School of English, Faculty of Philosophy of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English and American Studies. Supervisor: Dr. Tatiani Rapatzikou June 2020 Iliopoulos 2 Abstract This thesis explores the relationship between space and technology as well as the re-purposing of tangible and intangible materials in William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984) and Virtual Light (1993). With attention paid to the importance of the cyberpunk setting. Gibson approaches marginal spaces and the re-purposing that takes place in them. The current thesis particularly focuses on spotting the different kinds of re-purposing the two works bring forward ranging from body alterations to artificial spatial structures, so that the link between space and the malleability of materials can be proven more clearly. This sheds light not only on the fusion and intersection of these two elements but also on the visual intensity of Gibson’s writing style that enables readers to view the multiple re-purposings manifested in thε pages of his two novels much more vividly and effectively. Iliopoulos 3 Keywords: William Gibson, cyberspace, utilization of space, marginal spaces, re-purposing, body alteration, technology Iliopoulos 4 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Tatiani Rapatzikou, for all her guidance and valuable suggestions throughout the writing of this thesis. I would also like to express my gratitude to my parents for their unconditional support and understanding. -

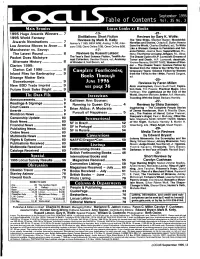

Table of Contents Vol. 35 No. 3

September 1995 Table of Contents vol. 35 no. 3 M a i n S t o r ie s Locus Looks a t Books 1995 Hugo Awards Winners... 7 - 13- - 21 - 1995 World Fantasy Distillations: Short Fiction Reviews by Gary K. Wolfe: Reviews by Mark R. Kelly: The Time Ships, Stephen Baxter; Bloodchild: Awards Nominations .............. 7 Asimov’s 11/95; F&SF 8/95; Analog 11/95; Inter Novellas and Stories, Octavia E. Butler; How to Lou Aronica Moves to Avon.... 8 zone 7/95; Omni Online 7/95; Omni Online 8/95. Save the World, Charles Sheffield, ed.; To Write Like a Woman: Essays in Feminism and Sci Manchester vs. Savoy: - 17- ence Fiction, Joanna Russ; Superstitious, R.L. The Latest Round..................... 8 Reviews by Russell Letson: Stine; The Horror at Camp Jellyjam, R.L. Stine; Pocket Does McIntyre The Year’s Best Science Fiction, Twelfth An The Dream Cycle of H.P. Lovecraft: Dreams of nual Collection, Gardner Dozois, ed ; Anatomy Terror and Death, H.P. Lovecraft; deadrush, Alternate History...................... 8 of Wonder 4, Neil Barron, ed. Yvonne Navarro; SHORT TAKE: Women of Won Clarion 1995; der - The Classic Years: Science Fiction by Women from the 1940s to the 1970s/The Con Clarion Call 1996 .................... 8 C o m p l ete For t hcoming temporary Years: Science Fiction by Women Inland Files for Bankruptcy ...... 9 from the 1970s to the 1990s, Pamela Sargent, Strange Matter Gets Books Thr ough ed. -25- Goosebumps.............................. 9 June 1996 Reviews by Faren Miller: New BDD Trade Imprint ........... 9 See p age 3 6 Alvin Journeyman, Orson Scott Card; Expira Future Book Sales Bright......... -

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 27212EN The Lion and the Mouse Beverley Randell 1.0 0.5 330EN Nate the Great Marjorie Sharmat 1.1 1.0 6648EN Sheep in a Jeep Nancy Shaw 1.1 0.5 9338EN Shine, Sun! Carol Greene 1.2 0.5 345EN Sunny-Side Up Patricia Reilly Gi 1.2 1.0 6059EN Clifford the Big Red Dog Norman Bridwell 1.3 0.5 9454EN Farm Noises Jane Miller 1.3 0.5 9314EN Hi, Clouds Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 9318EN Ice Is...Whee! Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 27205EN Mrs. Spider's Beautiful Web Beverley Randell 1.3 0.5 9464EN My Friends Taro Gomi 1.3 0.5 678EN Nate the Great and the Musical N Marjorie Sharmat 1.3 1.0 9467EN Watch Where You Go Sally Noll 1.3 0.5 9306EN Bugs! Patricia McKissack 1.4 0.5 6110EN Curious George and the Pizza Margret Rey 1.4 0.5 6116EN Frog and Toad Are Friends Arnold Lobel 1.4 0.5 9312EN Go-With Words Bonnie Dobkin 1.4 0.5 430EN Nate the Great and the Boring Be Marjorie Sharmat 1.4 1.0 6080EN Old Black Fly Jim Aylesworth 1.4 0.5 9042EN One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Bl Dr. Seuss 1.4 0.5 6136EN Possum Come a-Knockin' Nancy VanLaan 1.4 0.5 6137EN Red Leaf, Yellow Leaf Lois Ehlert 1.4 0.5 9340EN Snow Joe Carol Greene 1.4 0.5 9342EN Spiders and Webs Carolyn Lunn 1.4 0.5 9564EN Best Friends Wear Pink Tutus Sheri Brownrigg 1.5 0.5 9305EN Bonk! Goes the Ball Philippa Stevens 1.5 0.5 408EN Cookies and Crutches Judy Delton 1.5 1.0 9310EN Eat Your Peas, Louise! Pegeen Snow 1.5 0.5 6114EN Fievel's Big Showdown Gail Herman 1.5 0.5 6119EN Henry and Mudge and the Happy Ca Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9477EN Henry and Mudge and the Wild Win Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9023EN Hop on Pop Dr. -

Winter 2005 Clarion Workshop Newsletter

Number 24: IF YOU CAN’T STAND Winter 2005 THE HEAT... ...get out of the kitchen. And that’s exactly what the thirteen partici- pants of the 2005 Clarion Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers’ Work- shop did. Eschewing the trappings of cuisine and throwing nutritional caution to the wind, they thrived on sandwiches and cereal, producing 79 stories with an impressive, carbohydrate-fueled total of 370,400 words. Director: Elizabeth Zernechel Coordinator: Mary Sheridan Assistants: Sarah Gibbons, The participants came to this year’s workshop from eleven different Kate Fedewa states as well as Canada and Norway. Their educational backgrounds Web page: Dawn Martin ranged from Art to Physics to Psychology, and their professions were just as varied. Newsletter # 24 # Newsletter Clarion 2005 was taught by a talented staff of writers and editors: Joan Vinge, Charles Coleman Finlay, Cory Doctorow, Leslie What, Sheila Williams, Gwyneth Jones and Walter Jon Williams. In addition to teaching and critiquing, the writers-in-residence gave free public readings and signings at local book shops and libraries. ADDRESS SERVICE REQUESTED SERVICE ADDRESS East Lansing, MI 48824-1047 MI Lansing, East 112 Olds Hall Olds 112 Michigan State University State Michigan From left to right— Clarion Workshop Clarion Front Row: Way Jeng; Ian Tregillis; E. M. Zernechel; Kim Jollow Zimring; Traci N. Castleberry; Newsletter Christopher M. Knox. Middle Row: Tom Barlow; Alex Cybulski; Joan D. Vinge, Writer-in-Residence; Charles Coleman Finlay, Writer-in-Residence; T. L. Taylor. Back Row: Bjorn Harald Nordtveit; Kyle D. Kinder; Lister M. Matheson, Director; Bill Purcell; Sean T. Finn. Director’s Corner Please help Clarion continue.. -

Science Fiction Review 30 Geis 1979-03

MARCH-APRIL 1979 NUMBER 30 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW $1.50 Interviews: JOAN D. VINGE STEPHEN R. DONALDSON NORMAN SPINRAD Orson Scott Card - Charles Platt - Darrell Schweitzer Elton Elliott - Bill Warren SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW Formerly THE ALIEN CRITIC P.O. Be* 11408 MARCH, 1979 — VOL.8, no.2 Portland, OR 97211 WHOLE NUMBER 30 RICHARD E. GEIS, editor & publisher CONFUCIUS SAY MAN WHO PUBLISHES FANZINES ALL LIFE DOOMED TO PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY SEEK MIMEOGRAPH IN HEAVEN, HEKTO- COVER BY STEPHEN FABIAN JAN., MARCH, MAY, JULY, SEPT., NOV. Based on "Hellhole" by David Gerrold GRAPH IN HELL (To appear in ASIMOV'S SF MAGAZINE) SINGLE COPY — $1.50 ALIEN THOUGHTS by the editor........... 4 PUOTE: (503) 282-0381 INTERVIEW WITH JOAN D. VINGE CONDUCTED BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER....8 LETTERS---------------- THE VIVISECTOR GEORGE WARREN........... A COLUMN BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER. .. .14 JAMES WILSON............. PATRICIA MATTHEWS. POUL ANDERSON........... YOU GOT NO FRIENDS IN THIS WORLD # 2-8-79 ORSON SCOTT CARD.. A REVIEW OF SHORT FICTION LAST-MINUTE NEWS ABOUT GALAXY BY ORSON SCOTT CARD....................................20 NEAL WILGUS................ DAVID GERROLD........... Hank Stine called a moment ago, to THE AWARDS ARE Ca-IING!I! RICHARD BILYEU.... say that he was just back from New York and conferences with the pub BY ORSON SCOTT CARD....................................24 GEORGE H. SCITHERS ARTHUR TOFTE............. lisher. [That explains why his INTERVIEW WITH STEPHEN R. DONALDSON ROBERT BLOCH.............. phone was temporarily disconnected.] The GAIAXY publishing schedule CONDUCTED BY NEAL WILGUS.......................26 JONATHAN BACON.... SAM MOSKOWITZ........... is bi-monthly at the moment, and AND THEN I READ.... DARRELL SCHWEITZER there will be upcoming some special separate anthologies issued in the BOOK REVIEWS BY THE EDITOR..................31 CHARLES PLATT.......... -

The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis

University of Alberta Telling Stories About Storytelling: The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis by Orion Ussner Kidder A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Orion Ussner Kidder Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Dream • Explore • Imagine Stuffed Animal Writing & Collage Fashion Rendezvous Sleep Over Pg

.. Spring 2011 m pg. 3 e t s Imagine y Fashion Rendezvous S • y r a r b i L Explore Workshop pg.3 Workshop Writing & Collage Writing • Imagine that . that Imagine Dream Stuffed Animal Stuffed Sleep Over pg. 3 News, Events and Free Programs @ Camden County Library System Bellmawr Branch.....page 6 Avenue Branch...page 8 Ferry Branch.....page 9 Gloucester Township Branch....page 10 Haddon Township Merchantville Branch....page 12 South County Branch.....page 13 Branch.....page 15 Vogelson M. Allan Vogelson Regional Branch Library 203 Laurel Rd., Voorhees, NJ 08043 camdencountylibrary.org Coming e 4 & 5 Jun ’s Vogelson ook Sale iggest B B EVER! Library Director Linda A. Devlin Associate Director Deborah Ellis Dennis Library Commissioners Susan Bass Levin, President Nancy Costantino, Vice President, Patrick Abusi, Edward Brennan, Joyce Ellis, James Jefferson, Robert Weil Camden County Officials Louis Cappelli, Jr. Freeholder Director Carmen Rodriguez Freeholder Edward McDonnell Freeholder Deputy Director Joseph Ripa County Clerk Rodney A. Greco Freeholder Charles H. Billingham Sheriff Jeffrey L. Nash Patricia Egan Jones Freeholder Surrogate Ian Leonard Freeholder Editor/Designer: Pat Dempsey Assistant Editors: Debbie Dennis Mark Amorosi Maureen Wynkoop L i b r a r y S y s t e m Stuffed Spring Closings Animal Friday, April 22......Good Friday......Open Sunday, April 24.......Easter......Closed Wednesday, May18.....Staff Day..... Closed Monday, May 30.......Memorial Day.........Closed Sleepover Camden County Library System is governed and supported -

Made with Creative Commons MADE with CREATIVE COMMONS

ii Made With Creative Commons MADE WITH CREATIVE COMMONS PAUL STACEY AND SARAH HINCHLIFF PEARSON Made With Creative Commons iii Made With Creative Commons by Paul Stacey & Sarah Hinchliff Pearson © 2017, by Creative Commons. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license (CC BY-SA), version 4.0. ISBN 978-87-998733-3-3 Cover and interior design by Klaus Nielsen, vinterstille.dk Content editing by Grace Yaginuma Illustrations by Bryan Mathers, bryanmathers.com Downloadable e-book available at madewith.cc Publisher: Ctrl+Alt+Delete Books Husumgade 10, 5. 2200 Copenhagen N Denmark www.cadb.dk [email protected] Printer: Drukarnia POZKAL Spółka z o.o. Spółka komandytowa 88-100 Inowrocław, ul. Cegielna 10/12, Poland This book is published under a CC BY-SA license, which means that you can copy, redistribute, remix, transform, and build upon the content for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. License details: creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ Made With Creative Commons is published with the kind support of Creative Commons and backers of our crowdfunding-campaign on the Kickstarter.com platform. iv Made With Creative Commons “I don’t know a whole lot about non- fiction journalism. The way that I think about these things, and in terms of what I can do is. essays like this are occasions to watch somebody reason- ably bright but also reasonably average pay far closer attention and think at far more length about all sorts of different stuff than most of us have a chance to in our daily lives.” - DAVID FOSTER WALLACE Made With Creative Commons v vi Made With Creative Commons CONTENTS Foreword xi Introduction xv PART 1: THE BIG PICTURE 1 The New World of Digital Commons by Paul Stacey 3 The Commons, the Market, and the State . -

The Peripheral Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE PERIPHERAL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK William Gibson | 400 pages | 01 Nov 2014 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780670921560 | English | London, United Kingdom The Peripheral PDF Book We are experiencing technical difficulties. If the first 50 pages of a book are so garbled with terms context can't help a reader unravel, then they're going to put the book down and never come back to it. So here we are thirty years later, William Gibson is 66 years old, and has just published his eleventh novel although I want to say twelve, but Burning Chrome is actually short stories. She's clear and easy to hear. This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. And Amazon has been betting big on lofty sci-fi and fantasy projects. Hobbled, naked, into the bathroom. Returning from his trip, Burton tells Flynne that Milagros Coldiron wants to speak with her. October Streaming Picks. It would be cool to see Flynne again. The end. Please try again later. Gibson does the exact same, and this is why, in his own words, his writing process is painstakingly slow. Honestly the exercise only served to provide evidence that the action and description in this novel were poorly balanced. Imagining how that technology would work — what would be funny about it and what would be disorienting and queasy-making — is one of the absolute triumphs of this book. His eyes, a size too large for their sockets, felt gritty. Archived from the original on September 16, She read me the questions and entered my answers into the quiz so I did not actually have to stand up and ruin my achievement of perfect sloth. -

Guided Reading Book List

Title Author Level Anno’s Counting Book Mitsumasa Anno A Count and See Tana Hoban A Dig, Dig Leslie Wood A Do You Want to Be My Friend? Eric Carle A Flowers Karen Hoenecke A Growing Colors Bruce McMillan A In My Garden Moria McLean A Look What I Can Do Jose Aruego A Sea Shapes Suse MacDonald A Taking a Walk Rebecca Emberley A What Do Insects Do? S. Canizares & P. Chanko A What Has Wheels? Karen Hoenecke A Getting There Young B Hats Around the World Liza Charlesworth B Have You Seen My Cat? Eric Carle B Have You Seen My Duckling? Nancy Tafuri B Here’s Skipper Lynn Salem & J. Stewart B How Many Fish? Caron Lee Cohen B I Can Help Stan Wilhelm B I Can Write, Can You? Lynn Salem & J. Stewart B Let’s Go Visiting Sue Williams B Look, Look, Look Tana Hoban B Mommy, Where Are You? Ziefert & Boon B Runaway Monkey Lynn Salem & J. Stewart B So Can I Margery Facklam B Sunburn Ann Prokopchak B Thank You Betsey Chessen B Two Points J. Kennedy & A. Eaton B Under the Bed Bruce Larkin B Water/Who Lives in a Tree?/Who Lives in the Arctic Susan Canizares B Title Author Level All Fall Down Brian Wildsmith C Apples Deborah Williams C Bears Bobbie Kalman C Big Long Animal Song Mike Artwell C Brown Bear, Brown Bear What Do You See? Bill Martin C Cats Deborah Williams C I See Monkeys Deborah Williams C I Want a Pet Barbara Gregorich C I Want To Be a Clown Sharon Johnson C Joshua James Likes Trucks Catherine Petrie C Leaves Karen Hoenecke C Looking for Halloween Karen Evans C Monsters Diane Namm C My Kite Deborah Williams C Octopus Goes to School Carolyn Bordelon C One Hunter Pat Hutchins C Pancakes for Breakfast Tomie dePaola C Rain R.