Muttuswami Dikshitar (1775-1835)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Music Academy, Madras 115-E, Mowbray’S Road

Tyagaraja Bi-Centenary Volume THE JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS A QUARTERLY DEVOTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MUSIC Vol. XXXIX 1968 Parts MV srri erarfa i “ I dwell not in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins, nor in the Sun; (but) where my Bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada l ” EDITBD BY V. RAGHAVAN, M.A., p h .d . 1968 THE MUSIC ACADEMY, MADRAS 115-E, MOWBRAY’S ROAD. MADRAS-14 Annual Subscription—Inland Rs. 4. Foreign 8 sh. iI i & ADVERTISEMENT CHARGES ►j COVER PAGES: Full Page Half Page Back (outside) Rs. 25 Rs. 13 Front (inside) 20 11 Back (Do.) „ 30 „ 16 INSIDE PAGES: 1st page (after cover) „ 18 „ io Other pages (each) „ 15 „ 9 Preference will be given to advertisers of musical instruments and books and other artistic wares. Special positions and special rates on application. e iX NOTICE All correspondence should be addressed to Dr. V. Raghavan, Editor, Journal Of the Music Academy, Madras-14. « Articles on subjects of music and dance are accepted for mblication on the understanding that they are contributed solely o the Journal of the Music Academy. All manuscripts should be legibly written or preferably type written (double spaced—on one side of the paper only) and should >e signed by the writer (giving his address in full). The Editor of the Journal is not responsible for the views expressed by individual contributors. All books, advertisement moneys and cheques due to and intended for the Journal should be sent to Dr. V. Raghavan Editor. Pages. -

Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Hindustani Name Chakra Sa C

The Indian Scale & Comparison with Western Staff Notations: The vowel 'a' is pronounced as 'a' in 'father', the vowel 'i' as 'ee' in 'feet', in the Sa-Ri-Ga Scale In this scale, a high note (swara) will be indicated by a dot over it and a note in the lower octave will be indicated by a dot under it. Hindustani Chakra Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Name MulAadhar Sa C - Natural Shadaj Shadaj (Base of spine) Shuddha Swadhishthan ri D - flat Komal ri Rishabh (Genitals) Chatushruti Ri D - Natural Shudhh Ri Rishabh Sadharana Manipur ga E - Flat Komal ga Gandhara (Navel & Solar Antara Plexus) Ga E - Natural Shudhh Ga Gandhara Shudhh Shudhh Anahat Ma F - Natural Madhyam Madhyam (Heart) Tivra ma F - Sharp Prati Madhyam Madhyam Vishudhh Pa G - Natural Panchama Panchama (Throat) Shuddha Ajna dha A - Flat Komal Dhaivat Dhaivata (Third eye) Chatushruti Shudhh Dha A - Natural Dhaivata Dhaivat ni B - Flat Kaisiki Nishada Komal Nishad Sahsaar Ni B - Natural Kakali Nishada Shudhh Nishad (Crown of head) Så C - Natural Shadaja Shadaj Property of www.SarodSitar.com Copyright © 2010 Not to be copied or shared without permission. Short description of Few Popular Raags :: Sanskrut (Sanskrit) pronunciation is Raag and NOT Raga (Alphabetical) Aroha Timing Name of Raag (Karnataki Details Avroha Resemblance) Mood Vadi, Samvadi (Main Swaras) It is a old raag obtained by the combination of two raags, Ahiri Sa ri Ga Ma Pa Ga Ma Dha ni Så Ahir Bhairav Morning & Bhairav. It belongs to the Bhairav Thaat. Its first part (poorvang) has the Bhairav ang and the second part has kafi or Så ni Dha Pa Ma Ga ri Sa (Chakravaka) serious, devotional harpriya ang. -

Syllabus for Post Graduate Programme in Music

1 Appendix to U.O.No.Acad/C1/13058/2020, dated 10.12.2020 KANNUR UNIVERSITY SYLLABUS FOR POST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN MUSIC UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SEMESTER SYSTEM FROM 2020 ADMISSION NAME OF THE DEPARTMENT: DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC NAME OF THE PROGRAMME: MA MUSIC DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC KANNUR UNIVERSITY SWAMI ANANDA THEERTHA CAMPUS EDAT PO, PAYYANUR PIN: 670327 2 SYLLABUS FOR POST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN MUSIC UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SEMESTER SYSTEM FROM 2020 ADMISSION NAME OF THE DEPARTMENT: DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC NAME OF THE PROGRAMME: M A (MUSIC) ABOUT THE DEPARTMENT. The Department of Music, Kannur University was established in 2002. Department offers MA Music programme and PhD. So far 17 batches of students have passed out from this Department. This Department is the only institution offering PG programme in Music in Malabar area of Kerala. The Department is functioning at Swami Ananda Theertha Campus, Kannur University, Edat, Payyanur. The Department has a well-equipped library with more than 1800 books and subscription to over 10 Journals on Music. We have gooddigital collection of recordings of well-known musicians. The Department also possesses variety of musical instruments such as Tambura, Veena, Violin, Mridangam, Key board, Harmonium etc. The Department is active in the research of various facets of music. So far 7 scholars have been awarded Ph D and two Ph D thesis are under evaluation. Department of Music conducts Seminars, Lecture programmes and Music concerts. Department of Music has conducted seminars and workshops in collaboration with Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts-New Delhi, All India Radio, Zonal Cultural Centre under the Ministry of Culture, Government of India, and Folklore Academy, Kannur. -

Ma Gurmat Sangeet

M.A. GURMAT SANGEET PART - II SEMESTER - III (2017-2018) Paper I HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE OF GURMAT SANGEET Time: 3 hrs. Max. Marks : 75 Internal Assessment : 25 Marks Pass Marks : 35 % Assessment Test : 15 Total Teaching Hours : 75 Attendance : 10 INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE PAPER-SETTER AND THE CANDIDATES The question paper will consist of three sections A, B & C. Sections A & B will have 5 questions of 8 marks each from the respective sections of the syllabus and acandidates are required to attempt three questions from each section. Section C will consist of 9 short answer type questions of 3 marks each, which will cover the entire syllabus uniformly. Students are required to attempt all questionos of Section C. Section - A 1. Evolution and Development of Gurmat Sangeet during a) Guru Nanak period b) Guru Angad Dev to Guru Arjan Dev period c) Guru Hargobind to Guru Gobind Singh period 2. Taksaal tradition of Gurmat Sangeet with reference to a) Damdami taksaal b) Jawaddi Taksaal 3. Contribution of Rabaabi tradition in Gurmat Sangeet. Section – B 1. Historical development of Kirtan Chauki tradition a) Upto Guru Arjan Dev period. b) Tradition of Sri Harimandir Sahib 2. Analytical study of basic sources of Gurmat Sangeet with reference to a) Sri Guru Granth Sahib b) Panth Parkaash 3. Contribution of different scholars towards Gurmat Sangeet with special reference to the 19th century. BOOKS PRESCRIBED 1 Gurmat Sangeet : Vibhin Pripekh, Gurnam Singh (Dr.) (Editor), Punjabi University Patiala, 1995 2. Gurmat Sangeet : Prabandh te Pasaar Gurnam Singh (Dr.), Punjabi University, Patiala. 2012 3. Gurmat Sangeet da Sangeet Vigyan, Varinder Kaur (Dr.), Amarjit Sahit Parkashan, Patiala 2005 4. -

Rakti in Raga and Laya

VEDAVALLI SPEAKS Sangita Kalanidhi R. Vedavalli is not only one of the most accomplished of our vocalists, she is also among the foremost thinkers of Carnatic music today with a mind as insightful and uncluttered as her music. Sruti is delighted to share her thoughts on a variety of topics with its readers. Rakti in raga and laya Rakti in raga and laya’ is a swara-oriented as against gamaka- complex theme which covers a oriented raga-s. There is a section variety of aspects. Attempts have of exponents which fears that ‘been made to interpret rakti in the tradition of gamaka-oriented different ways. The origin of the singing is giving way to swara- word ‘rakti’ is hard to trace, but the oriented renditions. term is used commonly to denote a manner of singing that is of a Yo asau Dhwaniviseshastu highly appreciated quality. It swaravamavibhooshitaha carries with it a sense of intense ranjako janachittaanaam involvement or engagement. Rakti Sankarabharanam or Bhairavi? rasa raga udaahritaha is derived from the root word Tyagaraja did not compose these ‘ranj’ – ranjayati iti ragaha, ranjayati kriti-s as a cluster under the There is a reference to ‘dhwani- iti raktihi. That which is pleasing, category of ghana raga-s. Older visesha’ in this sloka from Brihaddcsi. which engages the mind joyfully texts record these five songs merely Scholars have suggested that may be called rakti. The term rakti dhwanivisesha may be taken th as Tyagaraja’ s compositions and is not found in pre-17 century not as the Pancharatna kriti-s. Not to connote sruti and that its texts like Niruktam, Vyjayanti and only are these raga-s unsuitable for integration with music ensures a Amarakosam. -

The Rich Heritage of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg On

Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda ||Shree DwaDwarrrrkeshokesho Jayati|| || Shree Vallabhadhish Vijayate || The Rich Heritage Of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg on www.vallabhkankroli.org Reference : 8th Year Text Book of Pushtimargiya Patrachaar by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Inspiration: PPG 108 Shree Vrajeshkumar Maharajshri - Kankroli PPG 108 Shree Vagishkumar Bawashri - Kankroli Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Contents Meaning of Sangeet ........................................................................................................................... 4 Naad, Shruti and Swar ....................................................................................................................... 4 Definition of Raga.............................................................................................................................. 5 Rules for Defining Ragas................................................................................................................... 6 The Defining Elements in the Raga................................................................................................... 7 Vadi, Samvadi, Anuvadi, Vivadi [ Sonant, Consonant, Assonant, Dissonant] ................................ 8 Aroha, avaroha [Ascending, Descending] ......................................................................................... 8 Twelve Swaras of the Octave ........................................................................................................... -

M.A-Music-Vocal-Syllabus.Pdf

BANGALORE UNIVERSITY NAAC ACCREDITED WITH ‘A’ GRADE P.G. DEPARTMENT OF PERFORMING ARTS JNANABHARATHI, BANGALORE-560056 MUSIC SYLLABUS – M.A KARNATAKA MUSIC VOCAL AND INSTRUMENTAL (VEENA, VIOLIN AND FLUTE) CBCS SYSTEM- 2014 Dr. B.M. Jayashree. Professor of Music Chairperson, BOS (PG) M.A. KARNATAKA MUSIC VOCAL AND INSTRUMENTAL (VEENA, VIOLIN AND FLUTE) Semester scheme syllabus CBCS Scheme of Examination, continuous Evaluation and other Requirements: 1. ELIGIBILITY: A Degree with music vocal/instrumental as one of the optional subject with at least 50% in the concerned optional subject an merit internal among these applicant Of A Graduate with minimum of 50% marks secured in the senior grade examination in music (vocal/instrumental) conducted by secondary education board of Karnataka OR a graduate with a minimum of 50% marks secured in PG Diploma or 2 years diploma or 4 year certificate course in vocal/instrumental music conducted either by any recognized Universities of any state out side Karnataka or central institution/Universities Any degree with: a) Any certificate course in music b) All India Radio/Doordarshan gradation c) Any diploma in music or five years of learning certificate by any veteran musician d) Entrance test (practical) is compulsory for admission. 2. M.A. MUSIC course consists of four semesters. 3. First semester will have three theory paper (core), three practical papers (core) and one practical paper (soft core). 4. Second semester will have three theory papers (core), two practical papers (core), one is project work/Dissertation practical paper and one is practical paper (soft core) 5. Third semester will have two theory papers (core), three practical papers (core) and one is open Elective Practical paper 6. -

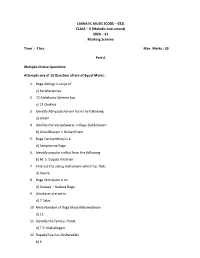

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Marking Scheme

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Marking Scheme Time - 2 hrs. Max. Marks : 30 Part A Multiple Choice Questions: Attempts any of 15 Question all are of Equal Marks : 1. Raga Abhogi is Janya of a) Karaharapriya 2. 72 Melakarta Scheme has c) 12 Chakras 3. Identify AbhyasaGhanam form the following d) Gitam 4. Idenfity the VarjyaSwaras in Raga SuddoSaveri b) GhanDharam – NishanDham 5. Raga Harikambhoji is a d) Sampoorna Raga 6. Identify popular vidilist from the following b) M. S. Gopala Krishnan 7. Find out the string instrument which has frets d) Veena 8. Raga Mohanam is an d) Audava – Audava Raga 9. Alankaras are set to d) 7 Talas 10 Mela Number of Raga Maya MalawaGoula d) 15 11. Identify the famous flutist d) T R. Mahalingam 12. RupakaTala has AksharaKals b) 6 13. Indentify composer of Navagrehakritis c) MuthuswaniDikshitan 14. Essential angas of kriti are a) Pallavi-Anuppallavi- Charanam b) Pallavi –multifplecharanma c) Pallavi – MukkyiSwaram d) Pallavi – Charanam 15. Raga SuddaDeven is Janya of a) Sankarabharanam 16. Composer of Famous GhanePanchartnaKritis – identify a) Thyagaraja 17. Find out most important accompanying instrument for a vocal concert b) Mridangam 18. A musical form set to different ragas c) Ragamalika 19. Identify dance from of music b) Tillana 20. Raga Sri Ranjani is Janya of a) Karahara Priya 21. Find out the popular Vena artist d) S. Bala Chander Part B Answer any five questions. All questions carry equal marks 5X3 = 15 1. Gitam : Gitam are the simplest musical form. The term “Gita” means song it is melodic extension of raga in which it is composed. -

1 ; Mahatma Gandhi University B. A. Music Programme(Vocal

1 ; MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B. A. MUSIC PROGRAMME(VOCAL) COURSE DETAILS Sem Course Title Hrs/ Cred Exam Hrs. Total Week it Practical 30 mts Credit Theory 3 hrs. Common Course – 1 5 4 3 Common Course – 2 4 3 3 I Common Course – 3 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 1 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 1 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 1 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 4 5 4 3 Common Course – 5 4 3 3 II Common Course – 6 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 2 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 2 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 2 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 7 5 4 3 Common Course – 8 5 4 3 III Core Course – 3 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 4 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 3 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 3 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 9 5 4 3 Common Course – 10 5 4 3 IV Core Course – 5 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 6 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 4 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 4 (Theory) 2 2 3 Core Course – 7 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 8 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts V Core Course – 9 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 10 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Open Course – 1 (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 1 2 1 Core Course – 11 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 12 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts VI Core Course – 13 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 14 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Elective (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 2 2 1 Total 150 120 120 Core & Complementary 104 hrs 82 credits Common Course 46 hrs 38 credits Practical examination will be conducted at the end of each semester 2 MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B. -

Andhra University 1 Year Diploma in (Music) Syllabus

SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATIN – ANDHRA UNIVERSITY 1st YEAR DIPLOMA IN (MUSIC) SYLLABUS (BOS approved and modified syllabus to be implemented from the admitted Batch 2012-13) Theory 100 Marks Paper I : Technical aspects of South Indian Classical Music 1. Technical Terms: a) Nada b) Sruti c) Swaras d) Swarasthanas e) Sathayi 2. Tala System: Sapta Talas, 35 Talas, Tala Dasa Prans, Chapu Tala Varieties Desadi and Madhyadi Talas 3. Musical Forms and their Lakshnas: Gitam, Varnam, Kritis, Kirtana, Padam, Ragamalika, Jasti Swaram, Swarajati, Tillana and Javali. 4. Lakshanas and Sancharas of the following Ragas: A a) Todi, b) Mayamalavagoula, c) Bhairavi, d) Kambhoji, e) Sankarabharanam f) Kalyani, g) Kharaharapriya, h) Mohana, i) Madhyamavathi j) Bilahari B. a) Dhanyasi, b) Saveri e)Vasanta d) HIndola e) Ananda Bhairavi f) Mukhari g) Kanada h) Khamas i) Begada j) Poorikalyani Paper II : Theoretical Aspects of South Indian Classical Music 100 Marks 1. Raaga and raga Lakshanam: a) Definition and Classification of ragas. b) Study of 13 Lakshanas c) ragalapana Padhathi 2. Musical Instruments and their classification 3. Special study of Tambura, Veena, Violin, Flute, Nagaswaram and Mridangam. 4. Characteristics of a composer. 5. Short biographical sketches of the following: a) Jayadeva b) Annamayya, c) Purandhara Dasa d) Narayana Tirtha e) Ramadasa f) Kshetrayya. Practical (First year) 100 Marks Paper III (Practical I) Fundamentals of Classical Music 1. a. Saraliswaras 6 b. Janta swaras 8 c. Alankaras 7 2. Gitas - 7 (Two Pillari Gitas, Two Ghanaraga Gitas, one Dhruva and one Lakshana gitam) 3. One Swarapallavi and one Swarajati 4. Five Adi Tala Varnas. -

Recording Release Forms 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Recording Date of Release Last Name First Name or Group Date Signed Tape Forms Recording 1 Siddick (Siddiq) Mohammed Sep 11, 1963 1 Sep 28, 1963 2 Khan Ramzan Nov 17, 1963 2A Nov 17, 1963 3 Kader Razak Oct 1, 1963 3A Oct 1, 1963 4 Barve Manahar Oct 11, 1963 3C-F Oct 10-11, 1963 5 Feb 23-24, 1964 6 Nabibax Ziauddin Oct 3, 1963 4A Oct 3, 1963 7 Ahemad Rafique Oct 3, 1963 4A Oct 3, 1963 8 Ishaque Mohammed Oct 3, 1963 4A Oct 3, 1963 9 Surdas Shamrao Banshode Oct 4, 1963 5A Oct 4, 1963 10 Jaffar Khan Abdul Hamid Oct 6, 1963 6A, 6B-6F Oct 6, 1963 11 Barve Madhukar Manahar (Manhar) Oct 10, 1963 7C Oct 10, 1963 12 Damle Anant (Anand) Shankar Oct 11, 1963 7D Oct 10-11, 1963 13 Qawal (Qawall) Yacoob Oct 16, 1963 8A, 8D 3 and 16 Oct, 1963 14 Madhukar P. Oct 10, 1963 8B Oct 10, 1963 15 Ghaisas Vimal Oct 15, 1963 8C Oct 15, 1963 16 Sable Shahir Oct 10, 1963 9A Oct 10, 1963 17 Shijwadkar (Shejwadkar) Jayashree Oct 17, 1963 11A Oct 17, 1963 18 Damle Anant (Ananta ) Shankar Oct 17, 1963 11A Oct 17, 1963 19 Jaffar Ali Mohammad Ali Oct 18, 1963 11B Oct 18, 1963 20 Kumthekar Krishnarao S. Nov 8, 1963 11C Nov 8, 1963 21 Damle Anant Shankar Oct 21, 1963 12A Oct 21, 1963 22 Joglekar Yogini Oct 21, 1963 12B Oct 21, 1963 23 Kamat Ramdas Oct 21, 1963 13A Oct 21, 1963 24 Khadilkar Indirabai Oct 21, 1963 13B Oct 21, 1963 25 Nevrekar Shripad Oct 21, 1963 13C Oct 21, 1963 26 Pendharkar B.V. -

Carnatic Music Primer

A KARNATIC MUSIC PRIMER P. Sriram PUBLISHED BY The Carnatic Music Association of North America, Inc. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Dr. Parthasarathy Sriram, is an aerospace engineer, with a bachelor’s degree from IIT, Madras (1982) and a Ph.D. from Georgia Institute of Technology where is currently a research engineer in the Dept. of Aerospace Engineering. The preface written by Dr. Sriram speaks of why he wrote this monograph. At present Dr. Sriram is looking after the affairs of the provisionally recognized South Eastern chapter of the Carnatic Music Association of North America in Atlanta, Georgia. CMANA is very privileged to publish this scientific approach to Carnatic Music written by a young student of music. © copyright by CMANA, 375 Ridgewood Ave, Paramus, New Jersey 1990 Price: $3.00 Table of Contents Preface...........................................................................................................................i Introduction .................................................................................................................1 Swaras and Swarasthanas..........................................................................................5 Ragas.............................................................................................................................10 The Melakarta Scheme ...............................................................................................12 Janya Ragas .................................................................................................................23