History the Anglo-Saxon Cross 1665 Plague Outbreak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eyam | Derbyshire | S32 5QW

2 Fiddlers Mews Fiddlers Bridge | Main Road | Eyam | Derbyshire | S32 5QW 2 FIDDLERS MEWS.indd 1 01/07/2019 14:13 Seller Insight This welcoming family home sits within the beautiful, picturesque village of Eyam in the Peak District,” say the vendors of 2 Fiddlers Mews, “with excellent local cafes and pubs. Eyam is the perfect place for long summer walks through the countryside and is a highly desirable village to live in. The village has great public transport links, with a bus stop right outside the front door, that can get you to all the surrounding villages as well as Sheffield and Chesterfield, making this the perfect property for commuting to work.” Meanwhile, the 3 bedroom mews house lends itself to everyday family life and entertaining alike, with different spaces serving a variety of needs and occasions. “A lovely dining room, with views across the rolling countryside is perfect for entertaining guests and family,” say the vendors. “The dining area leads through double doors to the cosy living room which is perfect for an after dinner coffee. The courtyard provides ample parking for guests, so entertaining is always hassle free.” The outside space also has much to offer, making the most of summer sunshine and enjoying marvellous views. “The property has a gorgeous south facing garden that benefits from the warm afternoon sun,” say the vendors, “so is perfect for enjoying those long summer evenings. The garden also features a patio area with a sun awning to provide shade from the midday heat.” “With its spacious dining room making the most of spectacular countryside views, and a cosy living ideal for after dinner drinks, the property is just as suited to relaxed entertaining as it is to everyday family life.” “I will miss waking up to the beautiful views and being able to walk in the countryside practically outside of the front door. -

The JESSOP Consultancy Sheffield + Lichfield + Oxford

The JESSOP Consultancy Sheffield + Lichfield + Oxford Document no.: Ref: TJC2020.160 HERITAGE STATEMENT December 2020 NEWFOUNDLAND NURSERY, Sir William Hill Road, Eyam, Derbyshire INTRODUCTION SCOPE DESIGNATIONS This document presents a heritage statement for the The building is not statutorily designated. buildings at the former Newfoundland Nursery, Sir There are a number of designated heritage assets William Hill Road, Grindleford, Derbyshire (Figure 1), between 500m and 1km of the site (Figure 1), National Grid Reference: SK 23215 78266. including Grindleford Conservation Area to the The assessment has been informed through a site south-east; a series of Scheduled cairns and stone visit, review of data from the Derbyshire Historic circles on Eyam Moor to the north-west, and a Environment Record and consultation of sources of collection of Grade II Listed Buildings at Cherry information listed in the bibliography. It has been Cottage to the north. undertaken in accordance with guidance published by The site lies within the Peak District National Park. Historic England, the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists and Peak District National Park Authority as set out in the Supporting Material section. The JESSOP Consultancy The JESSOP Consultancy The JESSOP Consultancy Cedar House Unit 18B, Cobbett Road The Old Tannery 38 Trap Lane Zone 1 Business Park Hensington Road Sheffield Burntwood Woodstock South Yorkshire Staffordshire Oxfordshire S11 7RD WS7 3GL OX20 1JL Tel: 0114 287 0323 Tel: 01543 479 226 Tel: 01865 364 543 NEWFOUNDLAND NURSERY, Eyam, Derbyshire Heritage Statement - Report Ref: TJC2019.158 Figure 1: Site location plan showing heritage designations The JESSOP Consultancy 2 Sheffield + Lichfield + Oxford NEWFOUNDLAND NURSERY, Eyam, Derbyshire Heritage Statement - Report Ref: TJC2019.158 SITE SUMMARY ARRANGEMENT The topography of the site falls steadily towards the east, with the buildings situated at around c.300m The site comprises a small group of buildings above Ordnance datum. -

Dale Head House Foolow | Eyam | Hope Valley | S32 5QB DALE HEAD HOUSE

Dale Head House Foolow | Eyam | Hope Valley | S32 5QB DALE HEAD HOUSE Set within two acres of beautiful gardens and grounds and completely enveloped by nothing but mile upon mile of rolling countryside is Dale Head House, an extremely well proportioned and immaculately presented family home that over time has been sympathetically updated. A large four bedroomed detached house beautifully appointed with spacious open rooms which stands prominently in two acres of garden and paddock and has spectacular views over the limestone plateau in all directions and close to the sought after Foolow village. The property has been enlarged over the years and has evolved to offer a superbly appointed family home and would suit those actively retired and discerning buyers with equestrian interests. Rooms have been opened to offer spacious modern areas for living and to offer unrivalled views of the Peak District. Modernised tastefully and with facilities and utilities right up to date this is a lovely opportunity to settle in a remarkable location where there are endless recreational facilities, good schools and major commercial centres within easy reach just outside the Peak District National Park. Ground floor A central hall has a stair to the first floor and leads onto a comfortable sitting room, this room has a dual aspect, a lovely cast iron fireplace and the floor is oak boarded. In contrast the dining room has been opened out to the very large farmhouse kitchen. This is a remarkable hub of this family home and a natural place for gathering and social dining around the log burning stove. -

Proposed Revised Wards for Derbyshire Dales District Council

Proposed Revised Wards for Derbyshire Dales District Council October 2020 The ‘rules’ followed were; Max 34 Cllrs, Target 1806 electors per Cllr, use of existing parishes, wards should Total contain contiguous parishes, with retention of existing Cllr total 34 61392 Electorate 61392 Parish ward boundaries where possible. Electorate Ward Av per Ward Parishes 2026 Total Deviation Cllr Ashbourne North Ashbourne Belle Vue 1566 Ashbourne Parkside 1054 Ashbourne North expands to include adjacent village Offcote & Underwood 420 settlements, as is inevitable in the general process of Mappleton 125 ward reduction. Thorpe and Fenny Bentley are not Bradley 265 immediately adjacent but will have Ashbourne as their Thorpe 139 focus for shops & services. Their vicar lives in 2 Fenny Bentley 140 3709 97 1855 Ashbourne. Ashbourne South has been grossly under represented Ashbourne South Ashbourne Hilltop 2808 for several years. The two core parishes are too large Ashbourne St Oswald 2062 to be represented by 2 Cllrs so it must become 3 and Clifton & Compton 422 as a consequence there needs to be an incorporation of Osmaston 122 rural parishes into this new, large ward. All will look Yeldersley 167 to Ashbourne as their source of services. 3 Edlaston & Wyaston 190 5771 353 1924 Norbury Snelston 160 Yeaveley 249 Rodsley 91 This is an expanded ‘exisitng Norbury’ ward. Most Shirley 207 will be dependent on larger settlements for services. Norbury & Roston 241 The enlargement is consistent with the reduction in Marston Montgomery 391 wards from 39 to 34 Cubley 204 Boylestone 161 Hungry Bentley 51 Alkmonton 60 1 Somersal Herbert 71 1886 80 1886 Doveridge & Sudbury Doveridge 1598 This ward is too large for one Cllr but we can see no 1 Sudbury 350 1948 142 1948 simple solution. -

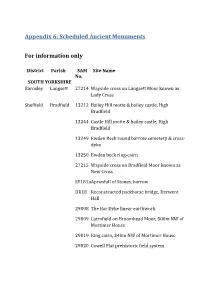

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments for Information Only

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments For information only District Parish SAM Site Name No. SOUTH YORKSHIRE Barnsley Langsett 27214 Wayside cross on Langsett Moor known as Lady Cross Sheffield Bradfield 13212 Bailey Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13244 Castle Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13249 Ewden Beck round barrow cemetery & cross- dyke 13250 Ewden beck ring-cairn 27215 Wayside cross on Bradfield Moor known as New Cross SY181a Apronfull of Stones, barrow DR18 Reconstructed packhorse bridge, Derwent Hall 29808 The Bar Dyke linear earthwork 29809 Cairnfield on Broomhead Moor, 500m NW of Mortimer House 29819 Ring cairn, 340m NW of Mortimer House 29820 Cowell Flat prehistoric field system 31236 Two cairns at Crow Chin Sheffield Sheffield 24985 Lead smelting site on Bole Hill, W of Bolehill Lodge SY438 Group of round barrows 29791 Carl Wark slight univallate hillfort 29797 Toad's Mouth prehistoric field system 29798 Cairn 380m SW of Burbage Bridge 29800 Winyard's Nick prehistoric field system 29801 Ring cairn, 500m NW of Burbage Bridge 29802 Cairns at Winyard's Nick 680m WSW of Carl Wark hillfort 29803 Cairn at Winyard's Nick 470m SE of Mitchell Field 29816 Two ring cairns at Ciceley Low, 500m ESE of Parson House Farm 31245 Stone circle on Ash Cabin Flat Enclosure on Oldfield Kirklees Meltham WY1205 Hill WEST YORKSHIRE WY1206 Enclosure on Royd Edge Bowl Macclesfield Lyme 22571 barrow Handley on summit of Spond's Hill CHESHIRE 22572 Bowl barrow 50m S of summit of Spond's Hill 22579 Bowl barrow W of path in Knightslow -

Guided Walks and Folk Trains in the High Peak and Hope Valley

High Peak and Hope Valley January – April 2020 Community Rail Partnership Guided Walks and Folk Trains in the High Peak and Hope Valley Welcome to this guide It contains details of Guided Walks and Folk Trains on the Hope Valley, Buxton and Glossop railway lines. These railway lines give easy access to the beautiful Peak District. Whether you fancy a great escape to the hills, or a night of musical entertainment, let the train take the strain so you can concentrate on enjoying yourself. High Peak and Hope Valley This leaflet is produced by the High Peak and Hope Valley Community Rail Partnership. Community Rail Partnership Telephone: 01629 538093 Email: [email protected] Telephone bookings for guided walks: 07590 839421 Line Information The Hope Valley Line The Buxton Line The Glossop Line Station to Station Guided Walks These Station to Station Guided Walks are organised by a non-profit group called Transpeak Walks. Everyone is welcome to join these walks. Please check out which walks are most suitable for you. Under 16s must be accompanied by an adult. It is essential to have strong footwear, appropriate clothing, and a packed lunch. Dogs on a short leash are allowed at the discretion of the walk leader. Please book your place well in advance. All walks are subject to change. Please check nearer the date. For each Saturday walk, bookings must be made by 12:00 midday on the Friday before. For more information or to book, please call 07590 839421 or book online at: www.transpeakwalks.co.uk/p/book.html Grades of walk There are three grades of walk to suit different levels of fitness: Easy Walks Are designed for families and the occasional countryside walker. -

REPORT for 1956 the PEAK DISTRICT & NORTHERN COUNTIES FOOTPATHS PRESERVATION SOCIETY- 1956

THE PEAK DISTRICT AND NORTHERN COUNTIES FOOTPATHS PRESERVATION SOCIETY 1 8 9 4 -- 1 9 56 Annual REPORT for 1956 THE PEAK DISTRICT & NORTHERN COUNTIES FOOTPATHS PRESERVATION SOCIETY- 1956 President : F . S. H. Hea<l, B.sc., PB.D. Vice-Presidents: Rt. Hon. The Lord Chorley F. Howard P. Dalcy A. I . Moon, B.A. (Cantab.) Council: Elected M embers: Chairman: T. B'oulger. Vice-Chairman: E. E. Ambler. L. L. Ardern J. Clarke L. G. Meadowcrort Dr. A. J. Bateman Miss M. Fletcher K. Mayall A. Ba:es G. R. Estill A. Milner D .T. Berwick A. W. Hewitt E. E. Stubbs J. E. Broom J. H. Holness R. T. Watson J. W. Burterworth J. E. l\lasscy H. E. Wild Delegates from Affiliated Clubs and Societies: F. Arrundale F. Goff H. Mills R. Aubry L. G riffiths L. Nathan, F.R.E.S. E .BaileY. J. Ha rrison J. R. Oweo I . G. Baker H. Harrison I. Pye J. D. Bettencourt. J. F. Hibbcrt H. Saodlcr A.R.P.S. A. Hodkinson J. Shevelan Miss D. Bl akeman W. Howarth Miss L. Smith R. Bridge W. B. Howie N. Smith T. Burke E. Huddy Miss M. Stott E. P. Campbell R. Ingle L. Stubbs R. Cartin L. Jones C. Taylor H. W. Cavill Miss M. G. Joocs H. F. Taylor J . Chadwick R. J. Kahla Mrs. W. Taylor F. J. Crangle T. H. Lancashire W. Taylor Miss F. Daly A. Lappcr P. B. Walker M:ss E. Davies DJ. Lee H. Walton W. Eastwood W. Marcroft G. H. -

257 X57 Valid From: 05 September 2021

Bus service(s) 257 X57 Valid from: 05 September 2021 Areas served Places on the route Sheffield Sheffield Interchange Crosspool The Moor Market Rivelin Dams Bamford (257) Sheffield Childrens Hospital Eyam (257) Derwent Reservoir (X57) Baslow (257) Ladybower Reservoir Bakewell (257) Manchester Airport (X57) Derwent (X57) Manchester (X57) Manchester Airport (X57) What’s changed Service 257 - No changes. Service X57 - Changes to the times of some journeys. Buses will also serve Hyde (Bus Station). Operator(s) Hulleys of Baslow How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for services 257 and X57 ! ! ! 17/12/2020# ! ! ! Derwent, Access Rd/Fairholmes Sheeld, Western Bank/ X57 continues to Glossop, 257, X57 ! Sheeld University ! Manchester, Coach Station Crosspool, !! and Manchester Airport Manchester Rd/Benty Ln ! !! ! Waverley X57 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 257 X57 ! ! X57 ! !! !! Sheeld, Interchange ! ! Ashopton, A57/Ladybower Inn !! Ashopton, Derwent Lane/Viaduct Crosspool, Mancheter Road/Vernon Terrace !! !! ! !! Hope Yorkshire Bridge, Ashopton Rd/Yorkshire Bridge Hotel ! Woodhouse Barber Booth 257 Gleadless! ! Hope, Castleton Rd/College ! ! ! ! Birley ! ! ! ! Bamford, Sickleholme/Bus Turnaround ! Norton Bradwell, Stretfield Road/Batham Gate Hathersage, Station Rd/Little John ! Mosborough Sparrowpit Operates via Lowedges Bradwell at 0850/1525 Peak Forest and Totley Marsh Lane Hope Valley College at 257 0845/1535 257 West Handley Grindleford, Main Rd/Mount Pleasant Great Hucklow, Foolow Road/Grindlow Lane -

Derbyshire Miscellany

DERBYSHIRE MISCELLANY The Local Hletory Bulletln of the Derbyshlre Archaeologlcal Soclety Volume 13 Autumn 7994 Part 6 DERBYSHIRE MISCELLANY Volume XII: Part 6 Autumn 1994 CONTENTS Page A Description of Derbyshire in 1-754 130 by Professor ].V. Beckett Wnt* in Eyam: frtracts fuffi the Jounal of Thottus Birds 131 by Dudley Fowkes Hasland Old Hall 736 by S.L. Garlic The7803 'Home Guard' 137 by Howard Usher Thelndustrial Arclnmlogy ol Ncw Mills 139 by Derek Brumhead ACase of Mineral Tithes 144 by Howard Usher S tao eI ey P opulation Changa 145 byA.D. Smith ASSISTANT EDITOR EDITOR TREASURER Jane Steer Dudley Fowkes T.J. l-arimore 478 Duffield Road, Staffordshirr Record Office 43 Reginald Road South Allestree, Eastgate Sheet, Chaddesden, Daby,DE222D[ Staffon{ 5T16 2LZ Derby DE21 5NG Copyright in each contribution to Derbyshire Miscellaay is reserved by the author. ts$t 041 7 0587 729 A DESCRTPTION OF DERBYSHIRE IN 1764 (by Professor J.V. Beckett, Professor of English Regional History, University of Nottingham Nottingham Park, Nottingham, NG7 2RD) Diarists almost invariably write at greater length and more interestingly about places they visit than about their home town or village. This can be a frustrating business for the historian. If the surviving diary is in a Record Office it is likely to be the Office of the place where the person lived, and a long contemporary description of Derby or Chesterfield maybe hidden away in Cornwall or Northumberland. An attenpt was made a few years ago to collate some of the material,r and the Royal Commission -

Derby to Manchester Railway Matlock to Buxton / Chinley Link Study Main Report Volume 1A: Version: Final

Derby to Manchester Railway Matlock to Buxton / Chinley Link Study Main Report Volume 1A: Version: Final June 2004 Derbyshire County Council Volume 1A: Main Report Version: Final Derby to Manchester Railway Matlock to Buxton / Chinley Link Study Derbyshire County Council ON BEHALF OF THE FOLLOWING FUNDING PARTNERS: • AMBER VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL • BUXTON AND THE PEAK DISTRICT SRB 6 PARTNERSHIP • COUNTRYSIDE AGENCY • DERBY CITY COUNCIL • DERBYSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL • DERBYSHIRE DALES DISTRICT COUNCIL • EAST MIDLANDS DEVELOPMENT AGENCY (EMDA) • EUROPEAN REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT FUND (ERDF) • GOVERNMENT OFFICE FOR THE EAST MIDLANDS (GOEM) • HIGH PEAK BOROUGH COUNCIL • PEAK DISTRICT NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY • PEAK PARK TRANSPORT FORUM • RURAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME • STRATEGIC RAIL AUTHORITY • TARMAC PLC DERBY TO MANCHESTER RAILWAY MATLOCK TO BUXTON / CHINLEY LINK STUDY Volume 1A: Main Report File Ref Volume 1A Main Report Final Issue A010338 Scott Wilson Railways Derbyshire County Council Volume 1A: Main Report Version: Final Derby to Manchester Railway Matlock to Buxton / Chinley Link Study DERBY TO MANCHESTER RAILWAY MATLOCK TO BUXTON / CHINLEY LINK STUDY Volume 1A: Main Report REPORT VERIFICATION Name Position Signature Date Prepared Bob Langford Study Manager 08/6/04 By: Checked Project Keith Wallace 08/6/04 By: Director Approved Project Keith Wallace 08/6/04 By: Director VERSION HISTORY Date Changes Since Last Version Issue Version Status 19 March None – Initial Issue for Comment by Advisory Draft Final 1 2004 Group 8 June 2004 Revised based on comments from Advisory Group FINAL 1 File Ref Volume 1A Main Report Final Issue A010338 Scott Wilson Railways Derbyshire County Council Volume 1A: Main Report Version: Final Derby to Manchester Railway Matlock to Buxton / Chinley Link Study DERBY TO MANCHESTER RAILWAY MATLOCK TO BUXTON/CHINLEY LINK STUDY Volume 1A: Main Report CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. -

100 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

100 bus time schedule & line map 100 Yorkshire Bridge - Bakewell Lady Manners School View In Website Mode The 100 bus line (Yorkshire Bridge - Bakewell Lady Manners School) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bakewell: 7:50 AM (2) Yorkshire Bridge: 4:15 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 100 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 100 bus arriving. Direction: Bakewell 100 bus Time Schedule 41 stops Bakewell Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:50 AM Lydgate Lane, Yorkshire Bridge Tuesday 7:50 AM Lydgate Cottages, Yorkshire Bridge Wednesday 7:50 AM Old Road, Bamford Thursday 7:50 AM Greenhead Park, Bamford Friday 7:50 AM Ashopton Road, Bamford Civil Parish Saturday Not Operational Derwent Hotel, Bamford The Croft, Bamford Civil Parish Victoria Road, Bamford Main Road, Bamford Civil Parish 100 bus Info Direction: Bakewell Station Road, Bamford Stops: 41 Station Road, Bamford Civil Parish Trip Duration: 60 min Line Summary: Lydgate Lane, Yorkshire Bridge, Saltergate Lane, Bamford Lydgate Cottages, Yorkshire Bridge, Old Road, Bamford, Greenhead Park, Bamford, Derwent Hotel, Bus Turnaround, Bamford Bamford, Victoria Road, Bamford, Station Road, Bamford, Saltergate Lane, Bamford, Bus Shatton Lane, Bamford Turnaround, Bamford, Shatton Lane, Bamford, Thornhill Lane, Bamford, The Rising Sun, Bamford, Thornhill Lane, Bamford Travellers Rest, Brough, Mill, Brough, Stretƒeld Cottages, Bradwell, Batham Gate, Bradwell, Memorial Hall, Bradwell, Church, Bradwell, Cop Low, The -

UNDER the EDGE INCORPORATING the PARISH MAGAZINE GREAT LONGSTONE, LITTLE LONGSTONE, ROWLAND, HASSOP, MONSAL HEAD, WARDLOW No

UNDER THE EDGE INCORPORATING THE PARISH MAGAZINE GREAT LONGSTONE, LITTLE LONGSTONE, ROWLAND, HASSOP, MONSAL HEAD, WARDLOW www.undertheedge.net No. 268 May 2021 ISSN 1466-8211 Stars in His Eyes The winner of the final category of the Virtual Photographic (IpheionCompetition uniflorum) (Full Bloom) with a third of all votes is ten year old Alfie Holdsworth Salter. His photo is of a Spring Starflower or Springstar , part of the onion and amyrillis family. The flowers are honey scented, which is no doubt what attracted the ant. Alfie is a keen photographer with his own Olympus DSLR camera, and this scene caught his eye under a large yew tree at the bottom of Church Lane. His creativity is not limited just to photography: Alfie loves cats and in Year 5 he and a friend made a comic called Cat Man! A total of 39 people took part in our photographic competition this year and we hope you had fun and found it an interesting challenge. We have all had to adapt our ways of doing things over the last year and transferring this competition to an online format, though different, has been a great success. Now that we are beginning to open up and get back to our normal lives, maybe this is the blueprint for the future of the competition? 39 people submitted a total of 124 photographs across the four categories, with nearly 100 taking part in voting for their favourite entry. Everyone who entered will be sent a feedback form: please fill it in withJane any Littlefieldsuggestions for the future.