A Study of the Life and Work of Christopher Durang: Laughing Wild Amidst Severest Woe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TACT 2013-14 Brochure

Photo by Stephen Kunken Stephen by Photo Cynthia Harris in in Harris Cynthia Lost in Yonkers in Lost - WALL STREET JOURNAL STREET WALL - “COMPANY OF THE YEAR!” THE OF “COMPANY 2013/2014 SEASON 2013/2014 New York, NY 10003 NY York, New 900 Broadway, Suite 905 905 Suite Broadway, 900 2013/2014 SEASON PLAYS AS TIMELYAS THEY ARE TIMELESS “COMPANY OF THE YEAR!” - WALL STREET JOURNAL Lovers Cameron Scoggins & Justine Salata in Photo by Hunter Canning In its 20th anniversary season, TACT is named the Wall Street Journal’s “COMPANY OF THE YEAR!” HOW ou top that by picking an astounding roster of provocative Yand entertaining plays, you pack them with brilliant talent, DO and invite New York City’s smartest and most discerning theatre-goers to attend (that’s you, by the way). Our Mainstage season opens in September with a rare look at a YOU lost classic; William Inge’s intense and startlingly contemporary Natural Affection. Rarely seen anywhere since its brief Broad- way run in 1963, this urban domestic drama created controversy with its underlying incestuous and homosexual insinuations and TOP its dark implications of a dawning sexual revolution. We can’t think of a better way to kick-off our season than by celebrating the centennial of an iconic American playwright with the redis- THAT? covery of this overlooked and undervalued gem. We’re pairing this daring drama with an early masterpiece from the hilarious and outlandish Christopher Durang, whose most re- cent work, Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike, won the 2013 Tony Award for Best Play. -

Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike

VANYA AND SONIA AND MASHA AND SPIKE BY CHRISTOPHER DURANG DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. VANYA AND SONIA AND MASHA AND SPIKE Copyright © 2014, Christopher Durang All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of VANYA AND SONIA AND MASHA AND SPIKE is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for VANYA AND SONIA AND MASHA AND SPIKE are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. -

2013-14Season Therapy Beyond

Scott Alan Evans, Cynthia Harris & Jenn Thompson Co-Artistic Directors VOLUME 21 No. 1 SUMMER 2013 the actors company theatre By COMPANY NEWS William Inge Directed By NEW SEASON ∙NEW LOOK ∙NEW SITE Jenn Thompson A violent love triangle that tests ACT’s 20th Anniversary season was the ties that bind. Ta benchmark in every way. The com- pany said “Happy Birthday” to itself with a special production of Happy Birthday by Anita Loos; it said “Goodbye” to Cathy By Bencivenga, its long-time and much be- Christopher loved General Manager; “Hello” to Christy Durang Ming-Trent its new General Manager; and Directed By Scott Alan Evans many many “Thank Yous” to the support- ers and contributors who helped make its Anniversary Spring Gala at the University BEYOND Club such an unmitigated success. It’s natural to use such a milestone year THERAPY as a pivot point to launch into the future. Life can be crazy. Therapy can help. The first revival of a long-lost classic. That is just what TACT is doing. We have a new logo and a new look – and will soon have a brand new website (coming late in the fall of 2014). And, of course, most important of all is the new season. Read all about it here, renew or become a new member, and check out what our compa- 2013-14 SEASON ny of actors has been up to. TACT welcomes Hilary Rainey to the staff Natural Affection, Beyond Therapy as our new Development Manager and Kathleen DeSilva, Danelle Feder, Andre Gonzalez, Caroline Kettig, Katherine Mc- Lennan, and Emma Thomasch, as mem- pposites attract, so they say. -

67Th Annual Tony Awards

The American Theatre Wing's The 2013 Tony Awards® Sunday, June 9th at 8/7c on CBS 67TH ANNUAL TONY AWARDS Best Play Best Performance by an Actress in a Leading Role in a Musical Best Costume Design of a Musical The! Assembled Parties (Richard Greenberg) Stephanie! J. Block, The Mystery of Edwin Drood Gregg! Barnes, Kinky Boots Lucky Guy (Nora Ephron) Carolee Carmello, Scandalous Rob Howell, Matilda The Musical The Testament of Mary (Colm Toíbín) Valisia LeKae, Motown The Musical Dominique Lemieux, Pippin Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike (Christopher Durang) Patina Miller, Pippin William Ivey Long, Rodgers + Hammerstein’s Cinderella Laura Osnes, Rodgers + Hammerstein’s Cinderella Best Musical Bring! It On: The Musical Best Performance by an Actor in a Featured Role in a Play Best Lighting Design of a Play A Christmas Story, The Musical Danny! Burstein, Golden Boy Jules! Fisher & Peggy Eisenhauer, Lucky Guy Kinky Boots Richard Kind, The Big Knife Donald Holder, Golden Boy Matilda The Musical Billy Magnussen, Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike Jennifer Tipton, The Testament of Mary Tony Shalhoub, Golden Boy Japhy Weideman, The Nance Best Book of a Musical Courtney B. Vance, Lucky Guy A! Christmas Story, The Musical (Joseph Robinette) Best Lighting Design of a Musical Kinky Boots (Harvey Fierstein) Best Performance by an Actress in a Featured Role in a Play Kenneth! Posner, Kinky Boots Matilda The Musical (Dennis Kelly) Carrie! Coon, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Kenneth Posner, Pippin Rodgers + Hammerstein’s Cinderella (Douglas Carter -

Miss Witherspoon

Otterbein University Digital Commons @ Otterbein 2007-2008 Season Productions 2001-2010 5-1-2008 Miss Witherspoon Otterbein University Theatre and Dance Department Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/production_2007-2008 Part of the Acting Commons, Dance Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Otterbein University Theatre and Dance Department, "Miss Witherspoon" (2008). 2007-2008 Season. 4. https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/production_2007-2008/4 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Productions 2001-2010 at Digital Commons @ Otterbein. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2007-2008 Season by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Otterbein. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OTTERBEIN COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF THEATRE AND DANCE Presents Christopher Durang’s Miss Wither spoon Directed by Ed Vaughan Scenic and Lighting Design Rob Johnson Costume Design Sound Design Wes Jenkins Peter Sichko May 1-3, 9&10, 2008 Campus Center Theatre cast Veronica.......................................................................................Caitlin Morris Maryamma............................................................................. Selina Verastigui Mother 1& Mother 2................................................................ Clare Schmidt Father 1& Father 2, Sleazy Man, Dog Owner, Wise Man.....Lucas Dixon Teacher, Woman in Hat............................................................Ayaunna Bibb production team -

Anton Chekhov

PLAY GUIDE About ATC 1 Introduction to the Play 2 Meet the Characters 2 Meet the Playwright 3 Anton Chekhov 4 Chekhov: A Brief Overview 5 References and Glossary 8 Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike Play Guide written and compiled by Katherine Monberg, ATC Literary Associate, with assistance from April Jackson, Learning & Education Manager; Bryanna Patrick and Luke Young, Learning & Education Associates SUPPORT FOR ATC’S EDUCATION AND COMMUNITY PROGRAMMING HAS BEEN PROVIDED BY: APS Rosemont Copper Arizona Commission on the Arts Stonewall Foundation Bank of America Foundation Target Blue Cross Blue Shield Arizona The Boeing Company City Of Glendale The Donald Pitt Family Foundation Community Foundation for Southern Arizona The Johnson Family Foundation, Inc Cox Charities The Lovell Foundation Downtown Tucson Partnership The Marshall Foundation Enterprise Holdings Foundation The Maurice and Meta Gross Foundation Ford Motor Company Fund The Max and Victoria Dreyfus Foundation Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Foundation The Stocker Foundation JPMorgan Chase The William L and Ruth T Pendleton Memorial Fund John and Helen Murphy Foundation Tucson Medical Center National Endowment for the Arts Tucson Pima Arts Council Phoenix Office of Arts and Culture Wells Fargo PICOR Charitable Foundation ABOUT ATC Arizona Theatre Company is a professional, not-for-profit theatre company This means all of our artists, administrators and production staff are paid professionals, and the income we receive from ticket sales and contributions goes right back into -

Conference Program

Connecting Jewish Theatre To the World CONFERENCE PROGRAM AJT Board/Staff Staff Executive Director: Jeremy Aluma Registrar/Finance: Marcy Segal Website Creative/Graphic Designer: Michelle Shapiro Conference Stage Manager/Program Designer: Danny Debner Executive Board President: Hank Kimmel Vice-president: Wendy Kout Vice-president: Ralph Meranto Vice-president: Deborah Baer Mozes Secretary: Jesse Bernstein Treasurer: Susan Lodish Immediate Past President: David Y. Chack Members-at-Large Social Media Manager: Danielle Levsky Toby Klein Greenwald Ronda Spinak Adam Immerwahr Robyn Israel Ex Officio Mira Hirsch Ellen Schiff Robert Skloot Honorary Board Tovah Feldshuh Adam Kantor Theodore Bikel (z”l) We wish to express our gratitude to the Performers’ Unions: ACTORS’ EQUITY ASSOCIATION AMERICAN GUILD OF MUSICAL ARTISTS AMERICAN GUILD OF VARIETY ARTISTS SAG-AFTRA through Theatre Authority, Inc. for their cooperation in permitting the Artists (Tessa Aubergenois, Arye Gross, Karen Malina White, Sally Wingert, Minka Wiltz, and Aviva Pressman) to appear on this program. Program Contents Day One Schedule – Sunday October 25 4 Mara Isaacs 5 Debórah Eliezer 6 Seraph-Eden Boroditsky 7 Lindsey Newman 8 Stories of Jewish Holidays 9 The Great Escape 10 Bubble Schmeisis (excerpt) 11 BJW (excerpt) 12 Imagining Heschel (excerpt) 13 Day Two Schedule – Monday October 26 14 Shimrit Ron 15 Igal Ezraty 16 Hadar Galron 17 Maya Arud Yasur 18 Noam Gil 19 Hanna Azoulay-Hasfari 20 Udi Ben Moshe 21 Joshua Harmon 22 Anike Tourse 23 András Borgula 24 Helen Marcos 25 Rachel -

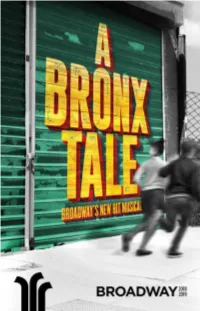

A-Bronx-Tale-Program-0F4ae47f5e

TOMMY MOTTOLA THE DODGERS TRIBECA PRODUCTIONS EVAMERE ENTERTAINMENT NEIGHBORHOOD FILMS in association with PAPER MILL PLAYHOUSE present Book by Music by Lyrics by CHAZZ PALMINTERI ALAN MENKEN GLENN SLATER Based on the Play by CHAZZ PALMINTERI with JOE BARBARA RICHARD H. BLAKE JOEY BARREIRO MICHELLE ARAVENA BRIANNA-MARIE BELL ANTONIO BEVERLY FRANKIE LEONI SHANE PRY MIKE BACKES MICHAEL BARRA SEAN BELL JOSHUA MICHAEL BURRAGE JOEY CALVERI GIOVANNI DiGABRIELE ALEX DORF JOHN GARDINER PETER GREGUS HALEY HANNAH KIRK LYDELL ASHLEY McMANUS CHRISTOPHER MESSINA ROBERT PIERANUNZI BRANDI PORTER KYLI RAE PAUL SALVATORIELLO BRITTANY WILLIAMS JASON WILLIAMS Scenic Design Costume Design Lighting Design Sound Design BEOWULF BORITT WILLIAM IVEY LONG HOWELL BINKLEY GARETH OWEN Hair and Wig Design Makeup Design Fight Coordinator Technical Supervision PAUL HUNTLEY ANNE FORD-COATES ROBERT WESTLEY HUDSON THEATRICAL ASSOCIATES Orchestrations Music Direction Period Music Consultant Music Coordinator DOUG BESTERMAN BRIAN P. KENNEDY JOHNNY GALE JOHN MILLER Associate Director Associate Choreographer Company Manager Production Stage Manager STEPHEN EDLUND MARC KIMELMAN JEFF MENSCH KELSEY TIPPINS Production Manager Casting Tour Booking, Marketing & Press General Management NETWORKS PRESENTATIONS TARA RUBIN CASTING BROADWAY BOOKING OFFICE NYC GENTRY & ASSOCIATES WALKER WHITE MERRI SUGARMAN, CSA GREGORY VANDER PLOEG Executive Producers Associate Producer DANA SHERMAN LAUREN MITCHELL SETH WENIG Music Supervision and Arrangements by RON MELROSE Choreography by SERGIO TRUJILLO -

FINDING HUMOUR in the PAIN Directing Christopher Durang and Albert Innaurato’S the Idiots Karamazov

FINDING HUMOUR IN THE PAIN Directing Christopher Durang and Albert Innaurato’s The Idiots Karamazov by Chris McGregor B.A. Drama, Bishop’s University, Lennoxville, Quebec 1987 A THESIS SUBMITTED N PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF FiNE ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Theatre) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August, 2009 © Chris McGregor, 2009 Abstract Finding Humour in the Pain-Directing Christopher Durang and Albert limaurato’s Play, The Idiots Karamazov examines the preparation, research, pre-production and rehearsal processes that went into staging The Idiots Karamazov at the University of British Columbia’s Frederic Wood Theatre from March l9to 28, 2009. This paper is broken down into 4 chapters detailing my goals to achieve a successful and relevant production for today’s audience. My rehearsal process was to inspire and guide all artists involved to act upon their creative impulses and to make this production a collaborative effort. Chapter 1 includes a biography of both playwrights, outlining their influences and a brief historical account ofhow The Idiots Karamazov evolved from an 8mm student film to a full-length professional production at Yale Repertory Theater. Chapter 2 provides a directorial analysis of the text and detailed methods and philosophies in directing from several well-known academics and theatre artists. Chapter 3 is a detailed journal chronicling the pre-production process including several e-mail correspondences with playwright, Christopher Durang. Also included in this chapter are several entries detailing early meetings with designers, daily accounts of the rehearsal process, production meetings, and fmally a description of three performances I attended during the run. -

The Invisible Hand at ACT Encore Arts Seattle

Kurt Beattie Carlo Scandiuzzi Artistic Director Executive Director ACT – A Contemporary Theatre presents Beginning October 17, 2014 • Opening Night October 23, 2014 CAST Sydney Andrews* Nina Cynthia Jones* Cassandra Marianne Owen* Sonia William Poole Spike Pamela Reed* Masha R. Hamilton Wright* Vanya CREATIVE TEAM Kurt Beattie Director Carey Wong Scenic Designer Catherine Hunt Costume Designer Michael Wellborn Lighting Designer Brendan Patrick Hogan Sound Designer Jeffrey K. Hanson* Stage Manager Erin B. Zatloka* Rehearsal Stage Manager Ruth Eitemiller Production Assistant Evan Christian Anderson Assistant Lighting Designer Kathryn Stewart Directing Intern Running Time: This performance runs approximately two hours. There will be one 15-minute intermission. *Members of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike is presented by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Service, Inc., New York. Originally produced on Broadway by: Joey Parnes, Larry Hirschhorn, Joan Raffe/Jhett Tolentino, Martin Platt & David Elliot, Pat Flicker Addiss, Catherine Adler, John O’Boyle, Joshua Goodman, Jamie deRoy/Richard Winkler, Cricket Hooper, Jiranek/Michael Palitz, Mark S. Golub & David S. Golub, Radio Mouse Entertainment, Shawdowcatcher Entertainment, Mary Cassette/Barbara Manocherian, Megan Savage/Meredith Lynsey Schade, Hugh Hysell/Richard Jordan, Cheryl Wiesenfeld/Ron Simons, S.D. Wagner, John Johnson in association with McCarter Theater Center and Lincoln Center Theater Originally commissioned and produced by McCarter Center Theater, Princeton, N.J. Emily Mann, Artistic Director; Timothy J. Shields, Managing Director; Mara Isaacs, Producing Director; and produced by Lincoln Center Theater, New York City under the direction of Andre Bishop and Bernard Gersten in 2012. -

American Playwrights on Beckett

AMERICAN PLAYWRIGHTS ON BECKETT Jonathan Kalb he following remarks by American playwrights on the subject of Samuel Beckett were gathered during January and February, 2006, in the course of researching a New York Times article on Beckett’s influence, published on TMarch 26, 2006, in anticipation of Beckett’s centenary on April 13. Most of the writers quoted here are prominent enough not to need lengthy introductions, but I have appended lists of their major works at the end. For me, the chief surprise of these exchanges was that nearly every playwright I contacted—even those whose work suggested little obvious affinity with Beckett—had thought about him a great deal and had much of value to say. Their comments deserved preservation beyond the brief excerpts that could be quoted in the Times. The playwrights were initially contacted via e-mail and asked to respond to the fol- lowing questions. Some chose to answer in recorded interviews, others by e-mail or fax. (1) What is Beckett’s importance to you? (What do you feel you learned from him?); (2) What can an aspiring young playwright learn from Beckett today? (What part should he play in a playwriting curriculum?); (3) Is Beckett’s value as a model for playwrights possibly limited by time or place? (Does the disparity matter, for instance, between Beckett’s stripped-down aesthetic, born of postwar desolation—his “art of impoverishment”—and expectations of plenty in the media age?) CHRISTOPHER DURANG My play The Actor’s Nightmare has semi-nightmare, semi-parody versions of Noel Coward, then Shakespeare, then Beckett. -

Execution of Justice

,86RXWK%HQG7KHDWUHDQG'DQFH&RPSDQ\ :LWQHVVHVIRUWKH3HRSOH SUHVHQWV 67(3+(16WKHFRURQHU 'DQLHO%OHYLQV 58'<127+(1%(5*'HSXW\0D\RU7UHYRU0RRUH %$5%$5$7$</25.&%6UHSRUWHU .DWKOHHQ0ROFKDQ ([HFXWLRQRI-XVWLFH 2)),&(5%<51(SROLFHZRPDQ6DPDQWKD6KHSDUG %\(PLO\0DQQ LQFKDUJHRIUHFRUGV :,//,$00(/,$-5FLYLOHQJLQHHU -DYRQ%DUQHV SP7KXUVGD\2FWREHU)ULGD\2FWREHU &<5&23(57,1,DSSRLQWPHQW &DVVDQGUD*DLQHV SP6XQGD\2FWREHU VHFUHWDU\WRWKH0D\RU &DPSXV$XGLWRULXP &$5/+(15<&$5/621DLGHWR0LON 'DQLHO%OHYLQV 5,&+$5'3$%,&+DVVLVWDQWWR0LON *H]D%DERFVDL 7+(&$67 )5$1.)$/=21&KLHI,QVSHFWRURI+RPLFLGH7UHYRU0RRUH &KDUDFWHUV (':$5'(5'(/$7=,QVSHFWRU 3DWULFN:DWWHUVRQ '$1:+,7( 7ULVWDQ&RQQHU 0$5<$11:+,7(KLVZLIH .DOD(ULFNVRQ :LWQHVVHVIRUWKH'HIHQVH ),5(&+,()6+(55$77 -DYRQ%DUQHV &233DWULFN:DWWHUVRQ 32/,&(2)),&(568//,9$1 'DQLHO%OHYLQV 6,67(5%220%220 *H]D%DERFVDL &,7<683(59,625/(('2/621 'DQLHO%OHYLQV ),5(0$1)5(',$1, 3DWULFN:DWWHUVRQ 7ULDO&KDUDFWHUV 36<&+,$75,676 '5-21(6 .DWKOHHQ0ROFKDQ &2857WKHMXGJH -DLPH%DKHQD '5%/,1'(5 'DQLHO%OHYLQV &/(5. -DYRQ%DUQHV '562/2021 7\OHU0DUFRWWH '28*/$66&+0,'7GHIHQVHODZ\HU 0DUORQ%XUQOH\ '5/81'( -RUG\Q1XWWLQJ 7+20$6)1250$1SURVHFXWLQJDWWRUQH\%UDG3RQWLXV '5'(/0$1 *H]D%DERFVDL -2$11$/,1179UHSRUWHU ,VDEHOOH+DQVRQ '(1,6($3&$5DLGHWR:KLWH 7\OHU0DUFRWWH -8525 &DVVDQGUD*DLQHV ,Q5HEXWWDOIRUWKH3HRSOH -8525 3DWULFN:DWWHUVRQ &$52/587+6,/9(5&LW\6XSHUYLVRU .DWKOHHQ0ROFKDQ -8525 7UHYRU0RRUH '5/(9<SV\FKLDWULVW 6DPDQWKD6KHSDUG -85<)25(0$1 &DVVDQGUD*DLQHV &KRUXVRI8QFDOOHG:LWQHVVHV 3URGXFWLRQFUHGLW"" -,0'(10$1H[XQGHUVKHULII:KLWH VMDLOHU'DQLHO%OHYLQV <281*027+(5ODWHVPRWKHURIWKUHH-RUG\Q1XWWLQJ 026&21( 6)5,(1'ROGSROLWLFDOFURQ\V7UHYRU0RRUH 0,/.¶6)5,(1' 3DWULFN:DWWHUVRQ ARTISTIC CREDITS DIRECTOR’S NOTES Director Randy Colborn Emily Mann is a multi-award-winning director and playwright Scenic Designer Yuri Cataldo celebrating her 25th season as artistic director of McCarter Theatre Lighting Designer Tim Hanson where she has overseen over 125 productions.