Lovecraft and Borges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

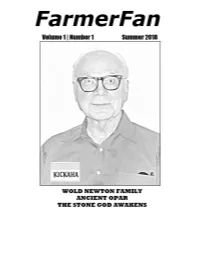

Farmerfan Volume 1 | Issue 1 |July 2018

FarmerFan Volume 1 | Issue 1 |July 2018 FarmerCon 100 / PulpFest 2018 Debut Issue Parables in Parabolas: The Role of Mainstream Fiction in the Wold Newton Mythos by Sean Lee Levin The Wold Newton Family is best known for its crimefighters, detectives, and explorers, but less attention has been given to the characters from mainstream fiction Farmer included in his groundbreaking genealogical research. The Swordsmen of Khokarsa by Jason Scott Aiken An in-depth examination of the numatenu from Farmer’s Ancient Opar series, including speculations on their origins. The Dark Heart of Tiznak by William H. Emmons The extraterrestrial origin of Philip José Farmer's Magic Filing Cabinet revealed. Philip José Farmer Bingo Card by William H. Emmons Philip José Farmer Pulp Magazine Bibliography by Jason Scott Aiken About the Fans/Writers Visit us online at FarmerFan.com FarmerFan is a fanzine only All articles and material are copyright 2018 their respective authors. Cover photo by Zacharias L.A. Nuninga (October 8, 2002) (Source: Wikimedia Commons) Parables in Parabolas The Role of Mainstream Fiction in the Wold Newton Mythos By Sean Lee Levin The covers to the 2006 edition of Tarzan: Alive and the 2013 edition of Doc Savage: His Apocalyptic Life Parables travel in parabolas. And thus present us with our theme, which is that science fiction and fantasy not only may be as valuable as the so-called mainstream of literature but may even do things that are forbidden to it. –Philip José Farmer, “White Whales, Raintrees, Flying Saucers” Of all the magnificent concepts put to paper by Philip José Farmer, few are as ambitious as his writings about the Wold Newton Family. -

Poetics of Enchantment: Language, Sacramentality, and Meaning in Twentieth-Century Argentine Poetry

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies Hispanic Studies 2011 POETICS OF ENCHANTMENT: LANGUAGE, SACRAMENTALITY, AND MEANING IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY ARGENTINE POETRY Adam Gregory Glover University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Glover, Adam Gregory, "POETICS OF ENCHANTMENT: LANGUAGE, SACRAMENTALITY, AND MEANING IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY ARGENTINE POETRY" (2011). Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies. 3. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/hisp_etds/3 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Hispanic Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. -

Perspectives on Borges' Library of Babel

Proceedings of Bridges 2015: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Culture Perspectives on Borges' Library of Babel CJ Fearnley Jeannie Moberly [email protected] [email protected] http://blog.CJFearnley.com http://Moberly.CJFearnley.com 240 Copley Road • Upper Darby, PA 19082 240 Copley Road • Upper Darby, PA 19082 Abstract This study builds on our Bridges 2012 work on Harmonic Perspective. Jeannie’s artwork explores 3D spaces with an intersecting plane construction. We used the subject of the remarkable “Universe (which others call the Library)” of Jorge Luis Borges. Our study explores the use of harmonic sequences and nets of rationality. We expand on our prior use of harmonics in Apollonian circles to a pencil of nonintersecting circles. Using matrix distortion and ambiguous direction in the multiple dimensions of a spiral staircase in the Library we break from harmonic measurements. We wonder about the contrasting perspectives of unimaginable finiteness and infiniteness. Figure 1 : Borges' Library of Babel (View of Apollonian Ventilation Shafts). Figure 2 : Borges' Library of Babel (Other View). Introduction In 1941, Jorge Luis Borges (1899–1986) published a short story The Library of Babel [2] that has intrigued artists, mathematicians, and philosophers ever since. The story plays with ideas of infinity, the very large but finite, the components of immensity, and periodicity. The Library consists of a vast number of hexagonal rooms each with the same number of books. Although each book is unique, each has the same number 443 Fearnley and Moberly of pages, lines, and characters. The librarians wander their whole lives through the labyrinth of rooms wondering about the nature of their Universe. -

Jorges Luis Borges and Italian Literature: a General Organic Approach

8 Jorges Luis Borges and Italian Literature: a general organic approach Alejandro Fonseca Acosta, Ph.D. candidate Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures (LLCU) McGill University, Montreal January 2018 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. © Alejandro Fonseca 2017 Table of Contents ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................... 1 DEDICATION................................................................................................................... 7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................. 8 0. INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................... 9 1. CHAPTER 1 THE MOST ITALIAN BORGES: HIS CULTURAL AND LITERARY BACKGROUND ................................................................................................... 38 1.1. WHAT TO EXPECT? .................................................................................................. 38 1.2. HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS .................................................................................... 38 1.3. BORGES’ CHILDHOOD IN PALERMO: FIRST CONTACT WITH ITALIAN POPULAR CULTURE ....................................................................................................................... 43 1.4. HIS FIRST ITALIAN READINGS ................................................................................. -

A History of Science Fiction and Fandom in Argentina

THE MELBOURNE r SCIENCE FICTION CLUB LIBRARY A HISTORY OF SCIENCE FICTION AND FANDOM IN ARGENTINA BY CLAUDIO OMAR NOGUEROL FIRST ENGLISH EDITION PRINTED JUNE, 1989 THE ENGLISH EDITION OF THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE FICTION ANS FANSOM IN ARGENTINA WAS WRITTEN BY CLAUDIO OMAR HOGUEROL AND IS EDITED, PUBLISHED AND PRINTED BY ROH k SUSAN CLARKE OF 6 BELLEUUE ROAD, FAULCONBRIDGE, NSW 2776, AUSTRALIA. IT IS A COMPANION UOLUME TO MOLESHORTH’S A HISTORY OF AUSTRALIAN FAN&OFf ISSN - JN66 (C> COPYRIGHT 1989 BY CLAUDIO OMAR HOGUEROL. fl BIT OF HISTORY: We'I 1 have a review of what has happened up to now in the Science Fiction sphere in this country. For this purpose, we'll divide this section into six parts or periods, taking into account those events which more or less continuously have affected the development of the genre. PROTOHISTORY ( - 1953) Modernism was the first articulated literary movement that began the creation of the fantastic theme, with the conscious will of writing a particular type of tale. Some of these already showed "scientific fantasy" outlines. The work of some writers comes to the forefront: Leopoldo Lugones and Ruben Dario, Eduardo Holdberg and Macedonio Fernandez, Roberto Arlt, Horacio Quiroga, Felisberto Hernandez and Francisco Piris, and latterly, Jorge Luis Borges, Adolfo Bioy Casares, Si Ivina Ucampo and Julio Cortazar. Lugones and Dario, notably influenced by Edgar Allen Poe, attempteo to investigate other dimensions, not only for their literary possibilities, but with a serious interest in the occultist and theophysical streams, and in the case of the argentine writer, with the (at the time) revolutionary theories of Einstein. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47044-5 — Jorge Luis Borges in Context Edited by Robin Fiddian Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47044-5 — Jorge Luis Borges in Context Edited by Robin Fiddian Index More Information Index ‘A Rafael Cansinos Assens’ (poem), 175 Asociación Amigos del Arte, 93, 95, 97 Abramowicz, Maurice, 33, 94 Aspectos de la poesía gauchesca (essays), 79 Acevedo de Borges, Leonor (Borges’s mother), Atlas (poetry and stories), 51, 54–55, 112 26–27 28 31 32–33 254 ʿ ā ī ī , , , , At˙˙t r, Far d al-D n Adrogué (stories), 43 overview of, 222–226, 260 Aira, César, 130–131, 133–135 Conference of the Birds, The and, 219, Aleph, The (stories), 234 222–223, 225 ‘Aleph, The’ (story), 29, 30, 61, 205, 232 Auster, Paul, 7, 246 Alfonsín, Raúl, 47, 51–52 author Alighieri, Dante. See Dante collective identity of, 115, 144, 150, 168, Amorím, Enrique, 21–22 221–222, 248–249 Anglo-Saxon, 7, 32, 102, 166, 244, 246 figure of, 5, 30, 72, 232, 248 anti-Semitism, 63, 120, 143, 199. See also Nazism unique identity of, 31, 141–142, 153–154 Antología poética argentina (anthology), 118 ‘Autobiographical Essay, An’ (essay), 201, 246 ‘Approach to Al-Mu’tasim, The’ (story), 225 avant-garde Argentina Argentine, heyday of, 28, 68, 89, 92–97, centenary of, 83, 85, 95, 181 107, 183 cultural context of, 6, 96, 100, 103, 109–110, 134 Argentine, decline of, 46, 54, 117, 184, 234 desaparecidos of, 16, 46, 52, 60, 65, 111 international, 22, 94, 95, 133, 253, 261 dictatorship of, 15–16, 111–112, 117, 238, 241 Spanish, 6, 28, 92–93, 166, 173–178 language of, 13, 145, 196 tango and, 110 literary tradition of, 77–78, 99–104, 130–135 ‘Avatars of the Tortoise’ (essay), 159 national identity and, 12–13, 72–73 ‘Avelino Arredondo’ (story), 23–24 politics of, 6, 43–48, 51–56, 111–112 ‘Averroës’ Search’ (story), 215 religion and, 195–197 See also Buenos Aires; Malvinas, Islas Babel (biblical city), 12–13, 85, 206–208 ‘Argentine Writer and Tradition, The’ (essay) Banda Oriental, the, 18–24 Argentina and, 132–133, 135, 245 barbarism. -

2004 World Fantasy Awards Information Each Year the Convention Members Nominate Two of the Entries for Each Category on the Awards Ballot

2004 World Fantasy Awards Information Each year the convention members nominate two of the entries for each category on the awards ballot. To this, the judges can add three or more nominees. No indication of the nominee source appears on the final ballot. The judges are chosen by the World Fantasy Awards Administration. Winners will be announced at the 2004 World Fantasy Convention Banquet on Sunday October 31, 2004, at the Tempe Mission Palms Hotel in Tempe, Arizona, USA. Eligibility: All nominated material must have been published in 2003 or have a 2003 cover date. Only living persons may be nominated. When listing stories or other material that may not be familiar to all the judges, please include pertinent information such as author, editor, publisher, magazine name and date, etc. Nominations: You may nominate up to five items in each category, in no particular order. You don't have to nominate items in every category but you must nominate in more than one. The items are not point-rated. The two items receiving the most nominations (except for those ineligible) will be placed on the final ballot. The remainder are added by the judges. The winners are announced at the World Fantasy Convention Banquet. Categories: Life Achievement; Best Novel; Best Novella; Best Short Story; Best Anthology; Best Collection; Best Artist; Special Award Professional; Special Award Non-Professional. A list of past award winners may be found at http://www.worldfantasy.org/awards/awardslist.html Life Achievement: At previous conventions, awards have been presented to: Forrest J. Ackerman, Lloyd Alexander, Everett F. -

Jorge Luis Borges Ficciones

Jorge Luis Borges Ficciones Hijo de una familia acomodada, Jorge Luis Borges nació en Buenos Aires el 24 de agosto de 1899 y murió en Ginebra, una de sus ciudades amadas, en 1986. Vivió, desde pequeño, rodeado de libros; y, entre 1914 y 1921, y más tarde en 1923, viajó a Europa, lo que le puso en contacto con las vanguardias del momento, a cuya estética se adhirió, especialmente al ultraísmo. En la primera mitad de esa década dirigió las revistas Prisma y Proa. Poeta, narrador y autor de ensayos personalísimos, ganó el premio Cervantes en 1980 y fue un eterno candidato al Nobel, ingresando en la ilustre nómina de quienes, como Proust, Kafka o Joyce, no lo consiguieron. Pero, como ellos, Borges pertenece por derecho propio al patrimonio cultural de la humanidad, y así está reconocido internacionalmente. Ficciones, libro aparecido en 1944, con el que ganó el Gran Premio de Honor de la Sociedad Argentina de Escritores, es uno de los más representativos de su estilo. En él están algunos de sus relatos más famosos, como «Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius»; «Pierre Menard, autor del Quijote»; «La biblioteca de Babel» o «El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan». En su caso, hablar de relatos es sólo un modo de entendernos, y a falta de un término más adecuado para designar esta magistral y sugestiva mezcla de erudición, imaginación, ingenio, profundidad intelectual e inquietud metafísica. Metáforas como la del laberinto, la biblioteca que coincide con el universo o la de la minuciosa reescritura del Quijote, pertenecen al centro del universo borgiano y, a través de sus millones de lectores en todas las lenguas, a la cultura universal. -

NORAH BORGES Mito Y Vanguardia

NORAH BORGES mito y vanguardia NORAH BORGES mito y vanguardia julio - agosto en el MNBA-Neuquén septiembre - octubre en el FNA 2006 Presidente de la Nación Argentina Néstor Kirchner Secretario de Cultura de la Presidencia de la Nación José Nun Intendente Municipalidad de Neuquén Horacio Quiroga Secretario de Cultura y Turismo Municipalidad de Neuquén Oscar Smoljan Director Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes Neuquén Oscar Smoljan Con esta muestra de trabajos de Norah Borges, las vanguardias de principios de los años 20 llegan al Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes Neuquén. Son las obras de una de las artistas plásticas más singulares y sensibles de nuestro país, precursora incuestio- nable, que creció, tanto personal como profesionalmente, casi al mismo tiempo que su hermano, Jorge Luis, lo hacía en el campo de las letras. Norah Borges forma parte de una época irrepetible de nuestro país. Un instante único del tiempo en el que dan a luz muchos de los más grandes apellidos del arte nacional, y en el cual se pone en marcha el proceso que impul- saría, a lo largo del siglo XX, los hilos de la cultura argentina, haciendo de nuestro país una potencia en el mundo. Pettoruti, Berni o Xul Solar, por mencionar sólo unos pocos, son algunos de los personajes que, junto a esta mujer, delinearon nuestra identidad por aquellos años. Norah es testigo privilegiada y a la vez protagonista indiscutida de esa maravillosa época de alumbramien- tos, génesis y formación de escuelas en todas las artes. Sus obras tienen la rara virtud de transitar ambos mundos: el de la plástica y el de la literatura. -

Miguel De Torre Borges

JORGE LUIS BORGES (1899-1986) w Miguel de Torre Borges On n’est pas toujours impunément le neveu de quelqu’un Proust (Sodome et Gomorrhe). EL TÍO, EL ÚNICO TÍO rranco con mi tío. Cuando lo empecé a conocer, no era Borges. Mi madre era A su hermana, luego él era mi tío, el único que había en la exigua fa milia —fue tan así, que los dos sobrinos lo llamábamos por la relación de parentesco, por la categoría: Tío. Nos llevábamos realmente bien: recuerdo que él me subía a babu- cha mientras tarareaba y bailaba con pasos de milonga: Pejerrey con papas / butifarra frita / la china que tengo / nadie me la quita ... (años des- pués yo encontraría la partitura en Cosas de negros de Vicente Rossi; la letra, también, después lo descubriría, era un ejemplo de ripio desca- rado para Tío.) Imitando la entonación de los personajes, me contaba cuentos di- vertidísimos, como el del explorador inglés en África que se casa con un gorila; al llegar la noticia a Inglaterra, las hermanas del no- vio, respetuosas de las convenciones, sólo se interesaban por el sexo del nuevo pariente y preguntaban: Is it a he-gorilla or. a she-gorilla? Variaciones Borges 18 (2004) 230 MIGUEL DE TORRE BORGES Y el tan festejado cuento del cocktail en casa del doctor Yarmo- linsky que, atendiendo a sus invitados, les decía: “Sírvase su noveno blintze, contador Ginzberg; anímese a su decimotercera porción de guefilte fish, profesor Abramovicz; haga un lugarcito para su sexto kreplach, escribano Nemirowsky; ¡que éste sea su último knische, li- cenciada Zylberman!” Cuando Baudelaire estaba estreñido —nos contaba a toda la fami- lia mientras comíamos— acudía a la farmacia para que lo aliviaran: Bonjour, monsieur l’apothicaire, est-ce que vous pourriez m’administrer un clystère? Cerca de París, me informaba, había un museo que atesoraba las sucesivas calaveras de Napoleón, desde la de cuando era chico en Ajaccio hasta la que tenía al morir en Santa Helena, pasando por la del puente de Arcole, la del momento en que el Papa lo coronó em- perador en Notre Dame, la de la isla de Elba y la de Waterloo. -

Norah Borges

NORAH BORGES Exposición Homenaje Agosto 2017 Creadora de Ángeles “Se que a mi lado hay una gran artista, que ve espontáneamente lo angelical del mundo que nos rodea” Jorge Luis Borges, Milán 1977 Leonor Fanny Borges nació en Buenos Aires en 1901. Su hermano, dos años mayor, le cambió el nombre. Será entonces Norah y tuvieron una relación entrañable. “En todos nuestros juegos era ella siempre el caudillo, yo el rezagado, el tímido, el sumiso. Ella subía a la azotea, trepaba a los árboles y a los cerros yo la seguía con menos entusiasmo que miedo (J. L. Borges, “Norah”) En 1914 se trasladó junto a su familia a Suiza, donde los encontró la Primera Guerra Mundial. Allí tomó contacto con las vanguardias, principalmente el movimiento expresionista. Estudió grabado, escultura y pintura, sus maestros fueron Maurice Sarkisoff, Ernest Kirchner y Arnaldo Bossi. La familia se trasladó en 1919 a España. El padre de los Borges sufría una ceguera progresiva (heredada, más tarde, por el autor de El Aleph) que no mitigaron los mejores oculistas de Ginebra. Eligieron Mallorca porque era hermosa, barata y con pocos turistas. Fue en esta ciudad donde Norah conformó su arte. Del paisaje balear, a Norah Borges le cautivó la figura de la mujer campesina a las que pintaba con sus cántaros de agua, llenas de humildad y bondad… Antecedentes remotos de sus ángeles. En Sevilla conoció al gran amor de su vida, Guillermo de Torre, escritor y crítico español, impulsor del ultraísmo. Y de su mano a Picasso, Miró, Unamuno y García Lorca. Estudió en Madrid con Romero de Torres.