2006 Japan Telecom Deal Value: Approx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Incoming Letter

I285 AVENUE OFTHE AMERICAS PAUL. WEISS. RIFKIND. WHARTON 8 GARRISON LLP NEWK)RK. IPI 1 0 0 1 ~ TELEPHONE (2 I21 373-5000 FACSIMILE 12 IP) 757-3900 #-)L 70'J 7%2F 7- t-2m#? !J Y2%RS*%*rn**%% 1015 L STREET. NW WASHINGTON. DC 20030-5004 NKOKU SElMEl BUILDING. 2-2 UCHlSAlWAlCHO 2-CHOME. CHIYODA-KU. TOKYO 100-001 I.JAPAN TELEPHONE (202) 223-73W FACSIMILE (202) 223-7420 TELEPHONE (03) 3597-8 I0l FACSIMILE (03)3587-8 120 ORIENTAL PW,TOWER €3 SUITE 1205 NO. I EAST CHANG AN AVENUE DONG CHENG DISTRICT BEIJING. 100738 PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA TELEPHONE (8O- 10) 8518-2700 FACSIMILE (80- t 0) (15 (8-2700/6 1 l2TH FLOOR, HONO KONG CLUB BUILDING 3A CHATER ROAD. CENTRAL HONQ KONG January 23,2006 TELEPHONE 1852) 253ESO35 FACSIMILE 1852) 2530-0022 ALDER CASTLE I0 NOBLE STREET LONDON ECZV 7JU. U.K. TELEPHONE (44 20) 7307 1000 U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission FACSIMILE I44 201 7307 1050 100 F Street, N.E. Washington, D.C. 20549 U.S.A. Attn: Mr. Brian V. Breheny, Chief Ms. Christina Chalk, Special Counsel Office of Mergers and Acquisitions Division of Corporation Finance Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, Inc. and Designated Subsidiaries Request to Report on Schedule 13G as Qualified Institutional Investors Ladies and Gentlemen: We are writing on behalf of Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, Inc. ("MUFG") and certain of its non-U.S. subsidiaries listed in Annex A attached hereto (the "Designated Subsidiaries") to request assurance that the Division of Corporation Finance (the "Division") will not recommend enforcement action by the U.S. -

Bank of Tokyo

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 20-F Annual and transition report of foreign private issuers pursuant to sections 13 or 15(d) Filing Date: 2006-09-28 | Period of Report: 2006-03-31 SEC Accession No. 0001193125-06-198464 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER BANK OF TOKYO - MITSUBISHI UFJ, LTD Mailing Address Business Address 1251 AVENUE OF THE 7-1 MARUNOUCHI 2-CHOME CIK:852743| IRS No.: 135611741 | Fiscal Year End: 0331 AMERICAS 15TH FLOOR CHIYODA-KU Type: 20-F | Act: 34 | File No.: 033-93414 | Film No.: 061112388 NEW YORK NY 10020-1104 TOKYO 100-8388, M0 00000 SIC: 6029 Commercial banks, nec 2127824547 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document Table of Contents As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on September 28, 2006 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F ¨ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR x ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended March 31, 2006 OR ¨ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period to OR ¨ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document Date of event requiring this shell company report Commission file number 333-11072 KABUSHIKI KAISHA MITSUBISHI TOKYO UFJ GINKO (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) THE BANK OF TOKYO- MITSUBISHI UFJ, LTD. -

1 Bay Area Companies That Match Employee Donations*

BAY AREA COMPANIES THAT MATCH EMPLOYEE DONATIONS* To our knowledge, the following local companies offer a matching gift when their employees make a personal donation to a nonprofit organization. This means that your employer may be willing to match all or part of your donation amount with its own donation. A “matching gift” is a donation made by a corporation or foundation on behalf of an employee that matches that employee’s contribution to a nonprofit organization. This can double, triple, or even quadruple your contribution! Our partial list of Bay Area corporations and foundations with matching gift programs is below. Contact your Human Resources department for information about your company’s program. If you find that your unlisted employer does offer a matching gift program, please let us know so that we can add them to our list. Thank you! *Our list was compiled from other lists found online and may not be comprehensive or up to date, so please check with your employer. Your employer will provide you with all the information needed to process your matching gift. 3Com Corporation AOL/Time Warner 3M Foundation AON Foundation Abbott Laboratories Fund Applera Corporation AC Vroman Inc. Applied Materials Accenture Aramark Corp. ACE INA Foundation Archer-Daniels-Midland Company Acrometal Companies Inc. Archie and Bertha Walker Foundation Acuson ARCO Foundation Adaptec, Inc. Argonaut Insurance Group ADC Telecommunications Arkwright Foundation, Inc. Addison Wesley Longman Arthur J. Gallagher Foundation Adobe Systems, Inc. Aspect Communications Corp. ADP Foundation Aspect Global Giving Program Advanced Fibre Communications Aspect Telecommunications Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) AT&T Foundation Advantis ATC AES Corporation ATK Sporting Equipment Aetna Foundation, Inc. -

Lista Azioni Negoziabili Quotate Sul Mercato Americano OTC Pink Marketplace

Lista Azioni Negoziabili Quotate sul Mercato Americano OTC Pink Marketplace Symbol Security CUSIP ISIN AAALY AAREAL BANK AG-UNSPON ADR 00254K108 US00254K1088 AACAY AAC TECHNOLOGIES H-UNSPON AD 304105 US0003041052 AACMZ ASIA CEMENT CORP-144A GDR 04515P104 US04515P1049 AAGIY AIA GROUP LTD-SP ADR 1317205 US0013172053 AAGRY ASTRA AGRO LESTARI-UNSP ADR 46301107 US0463011074 AATP AGAPE ATP CORP 8389108 US0083891087 AATRL [AMG 5.15 10/15/37] AMG CAPITAL TRUST II 00170F209 US00170F2092 AAVMY ABN AMRO BANK NV-UNSP ADR 00080Q105 US00080Q1058 ABBB AUBURN BANCORP INC 50254101 US0502541016 ABLT AMERICAN BILTRITE INC 24591406 US0245914066 ABNC ABN NV-CW50 HANG SENG CHIN 02407R105 US02407R1059 ABTZY ABOITIZ EQUITY VENTURES-ADR 3725306 US0037253061 ABVC AMERICAN BRIVISION HOLDING C 24733206 US0247332069 ABYB AMBOY BANCORPORATION 23226103 US0232261034 ABZPY ABOITIZ POWER CORP-UNSP ADR 3730108 US0037301084 ACCYY ACCOR SA-SPONSORED ADR 00435F309 US00435F3091 ACEEU ACE ETHANOL LLC - UNIT 00441B102 US00441B1026 ACGBY AGRICULTURAL BANK-UNSPON ADR 00850M102 US00850M1027 ACMC AMERICAN CHURCH MORTGAGE CO 02513P100 US02513P1003 ACMT ACMAT CORP 4616108 US0046161081 ACMTA ACMAT CORP -CL A 4616207 US0046162071 ACOPY THE A2 MILK CO LTD-UNSP ADR 2201101 US0022011011 ACSAY ACS ACTIVIDADES CONS-UNS ADR 00089H106 US00089H1068 ACTX ADVANCED CONTAINER TECHNOLOG 00791F109 US00791F1093 ADDC ADDMASTER CORP 6698203 US0066982036 ADDYY ADIDAS AG-SPONSORED ADR 00687A107 US00687A1079 ADERY AIDA ENGINEE LTD-UNSPON ADR 8712200 US0087122000 ADKIL ADKINS ENERGY LLC 7045107 US0070451077 -

Corporate Profile MUFG UNION BANK, N.A

MUFG AMERICAS HOLDINGS CORPORATION Corporate Profile MUFG UNION BANK, N.A. MUFG Union Bank, N.A., is a full-service bank with offices has strong capital reserves, credit ratings, and capital across the United States. We provide a wide spectrum ratios relative to peer banks. MUFG Union Bank is a proud of corporate, commercial, retail banking, and wealth member of the Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (NYSE: management solutions to meet the needs of customers. MTU), one of the world’s largest financial organizations The bank also offers an extensive portfolio of value-added with total assets of approximately ¥284.9 trillion (JPY) or solutions for customers, including investment banking, $2.3 trillion (USD),¹ as of June 30, 2015. MUFG Americas personal and corporate trust, capital markets, Holdings Corporation, the financial holding company, global custody, transaction banking, and other services. and MUFG Union Bank, N.A., have corporate headquarters With assets of $113.5 billion as of June 30, 2015, the bank in New York City. Enterprise Summary Retail Banking and Wealth Markets Commercial Banking (cont.) Asian Corporate Banking Retail Banking Project Finance Offices: Branch Banking: branches in Real Estate Industries Atlanta, GA California, Oregon, and Washington Technology Chicago, IL — Banking by Design™ checking Houston, TX — Online Banking & Bill Pay U.S. Corporate Banking Florence, KY — Mobile Text Banking & Commodity Finance Los Angeles, CA Check Deposit Energy Finance New York, NY Consumer Lending: Fixed and adjustable Financial Institutions -

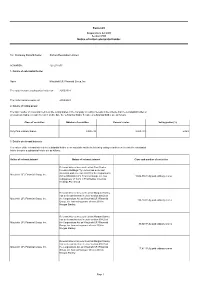

Form 603 Notice of Initial Substantial Holder

Form 603 Corporations Act 2001 Section 671B Notice of initial substantial holder To: Company Name/Scheme: Carbon Revolution Limited ACN/ARSN: 128 274 653 1. Details of substantial holder Name Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, Inc. The holder became a substantial holder on: 26/05/2021 The holder became aware on: 28/05/2021 2. Details of voting power The total number of votes attached to all the voting shares in the company or voting interests in the scheme that the substantial holder or an associate had a relevant interest in on the date the substantial holder became a substantial holder are as follows: Class of securities Number of securities Person's votes Voting power (%) Fully Paid ordinary shares 9,900,733 9,900,733 5.06% 3. Details of relevant interests The nature of the relevant interest the substantial holder or an associate had in the following voting securities on the date the substantial holder became a substantial holder are as follows: Holder of relevant interest Nature of relevant interest Class and number of securities Relevant interest in securities that First Sentier Investors Holdings Pty Limited has a relevant interest in under section 608(3) of the Corporations Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, Inc. Act as Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, Inc. has 9,604,598 Fully paid ordinary shares voting power of 100% in First Sentier Investors Holdings Pty Limited. Relevant interest in securities that Morgan Stanley has a relevant interest in under section 608(3) of Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, Inc. the Corporations Act as Mitsubishi UFJ Financial 188,184 Fully paid ordinary shares Group, Inc. -

Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group

Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group Annual Report 2008 Year ended March 31, 2008 Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (MUFG) is one of the world's largest and most diversified financial groups with total assets of around ¥1 90 trillion as of March 31, 2008. The group comprises five primary operating companies: The Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, Ltd., Mitsubishi UFJ Trust and Banking Corporation, Mitsubishi UFJ Securities Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi UFJ NICOS Co., Ltd. and Mitsubishi UFJ Lease & Finance Company Limited. MUFG's services include commercial banking, trust banking, securities, credit cards, consumer finance, asset management, leasing and many more fields of financial services. The group has the largest overseas network of any Japanese bank, comprising offices and subsidiaries, including Union Bank of California, in more than 40 countries. ● This annual report is prepared in accordance with U.S. GAAP. To read a discussion with the president and detailed descriptions of our business strategies and initiatives, please refer to MUFG’s Corporate Review 2008, which was published in August 2008. Contents All figures contained in this report are calculated according to Company Overview 1 U.S. GAAP, unless otherwise noted. Financial Highlights 3 This document contains statements that constitute forward-looking statements within the meaning of the United States Private Securities Annual Report on Form 20-F Litigation Reform Act of 1995. Such forward-looking statements represent targets that management will strive to achieve by implementing MUFG’s business -

MITSUBISHI UFJ FINANCIAL GROUP (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter) MITSUBISHI UFJ FINANCIAL GROUP, INC

ÌÃÕLà Ê1Ê>V>ÊÀÕ« !NNUAL2EPORT 9EARENDED-ARCH ÌÃÕLà Ê1Ê>V>ÊÀÕ«Ê1®ÊÃÊiÊvÊÌ iÊÜÀ`¿ÃÊ>À}iÃÌÊ>`ÊÃÌÊ`ÛiÀÃvi`Ê v>V>Ê }ÀÕ«ÃÊ ÜÌ ÊÌÌ>Ê >ÃÃiÌÃÊ vÊ >ÀÕ`Ê á£äÊ ÌÀÊ >ÃÊ vÊ >ÀV Ê Î£]Ê Óää°Ê / iÊ }ÀÕ«Ê V«ÀÃiÃÊvÛiÊ«À>ÀÞÊ«iÀ>Ì}ÊV«>iÃ]ÊVÕ`}Ê/ iÊ >ÊvÊ/ÞÌÃÕLà Ê1]Ê Ì`°]Ê ÌÃÕLÃ Ê 1Ê /ÀÕÃÌÊ >`Ê >}Ê À«À>Ì]Ê ÌÃÕLÃ Ê 1Ê -iVÕÀÌiÃÊ °]Ê Ì`°Ê >`Ê ÌÃÕLà Ê1Ê "-Ê °]ÊÌ`°Ê>`ÊÌÃÕLà Ê1Êi>ÃiÊEÊ>ViÊ «>ÞÊÌi`°Ê1¿ÃÊ ÃiÀÛViÃÊVÕ`iÊViÀV>ÊL>}]ÊÌÀÕÃÌÊL>}]ÊÃiVÕÀÌiÃ]ÊVÀi`ÌÊV>À`Ã]ÊVÃÕiÀÊv>Vi]Ê >ÃÃiÌÊ>>}iiÌ]Êi>Ã}Ê>`Ê>ÞÊÀiÊvi`ÃÊvÊv>V>ÊÃiÀÛViðÊ/ iÊ}ÀÕ«Ê >ÃÊÌ iÊ >À}iÃÌÊÛiÀÃi>ÃÊiÌÜÀÊvÊ>ÞÊ>«>iÃiÊL>]ÊV«ÀÃ}ÊvvViÃÊ>`ÊÃÕLÃ`>ÀiÃ]ÊVÕ`}Ê 1Ê >]ÊÊÀiÊÌ >Ê{äÊVÕÌÀið ●Ê / ÃÊ >Õ>Ê Ài«ÀÌÊ ÃÊ «Ài«>Ài`Ê Ê >VVÀ`>ViÊ ÜÌ Ê 1°-°Ê *°Ê/Ê Ài>`Ê >Ê `ÃVÕÃÃÊ ÜÌ Ê Ì iÊ «ÀiÃ`iÌÊ >`Ê `iÌ>i`Ê `iÃVÀ«ÌÃÊ vÊ ÕÀÊ LÕÃiÃÃÊ ÃÌÀ>Ìi}iÃÊ >`Ê Ì>ÌÛiÃ]Ê «i>ÃiÊ ÀiviÀÊ ÌÊ 1½ÃÊ À«À>ÌiÊ,iÛiÜÊÓää]ÊÜ V ÊÜ>ÃÊ«ÕLà i`ÊÊ-i«ÌiLiÀÊÓää° ÌiÌà Êv}ÕÀiÃÊVÌ>i`ÊÊÌ ÃÊÀi«ÀÌÊ>ÀiÊV>VÕ>Ìi`Ê>VVÀ`}ÊÌÊ1°-°Ê «>ÞÊ"ÛiÀÛiÜÊ ÊÊÊ£ *]ÊÕiÃÃÊÌ iÀÜÃiÊÌi`° >V>Ê} } ÌÃÊ ÊÊÎ / ÃÊ`VÕiÌÊVÌ>ÃÊÃÌ>ÌiiÌÃÊÌ >ÌÊVÃÌÌÕÌiÊvÀÜ>À`}Ê ÃÌ>ÌiiÌÃÊÜÌ ÊÌ iÊi>}ÊvÊÌ iÊ1Ìi`Ê-Ì>ÌiÃÊ*ÀÛ>ÌiÊ-iVÕÀÌiÃÊ Õ>Ê,i«ÀÌÊÊÀÊÓäÊÊ Ì}>ÌÊ,ivÀÊVÌÊvÊ£x°Ê-ÕV ÊvÀÜ>À`}ÊÃÌ>ÌiiÌÃÊ Ài«ÀiÃiÌÊÌ>À}iÌÃÊÌ >ÌÊ>>}iiÌÊÜÊÃÌÀÛiÊÌÊ>V iÛiÊLÞÊ«iiÌ}Ê 1½ÃÊLÕÃiÃÃÊÃÌÀ>Ìi}iÃ]ÊLÕÌÊ>ÀiÊÌÊ«ÀiVÌÃÊÀÊ>Ê}Õ>À>ÌiiÊvÊ vÕÌÕÀiÊ«iÀvÀ>Vi°ÊÊvÀÜ>À`}ÊÃÌ>ÌiiÌÃÊÛÛiÊÀÃÃÊ>`Ê ÕViÀÌ>ÌiÃ°Ê 1Ê >ÞÊ ÌÊ LiÊ ÃÕVViÃÃvÕÊ Ê «iiÌ}Ê ÌÃÊ LÕÃiÃÃÊ ÃÌÀ>Ìi}iÃ]Ê>`Ê>>}iiÌÊ>ÞÊv>ÊÌÊ>V iÛiÊÌÃÊÌ>À}iÌÃ]ÊvÀÊ>ÊÜ`iÊ À>}iÊvÊ«ÃÃLiÊÀi>ÃÃ]ÊVÕ`}ÊÀiViÌÊv>V>Ê>ÀiÌÊÃÌ>LÌÞÊ }L>ÞÊ>`ÊÌ iÊÃ}vV>ÌÊvÕVÌÕ>ÌÃÊÊÃiVÕÀÌiÃÊ>ÀiÌÃÊ>ÃÊ>ÊÀiÃÕÌÊ vÊÃÕV ÊÃÌ>LÌÞÆÊ>`ÛiÀÃiÊiVVÊV`ÌÃÊ>`Ê`iVÀi>Ãi`ÊLÕÃiÃÃÊ >VÌÛÌÞÊÊ>«>]ÊÌ -

SCHWAB STRATEGIC TRUST Form N-CSR Filed 2020-11-06

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM N-CSR Certified annual shareholder report of registered management investment companies filed on Form N-CSR Filing Date: 2020-11-06 | Period of Report: 2020-08-31 SEC Accession No. 0001193125-20-287821 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER SCHWAB STRATEGIC TRUST Mailing Address Business Address 211 MAIN STREET 211 MAIN STREET CIK:1454889| IRS No.: 000000000 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 1231 SAN FRANCISCO CA 94105 SAN FRANCISCO CA 94105 Type: N-CSR | Act: 40 | File No.: 811-22311 | Film No.: 201293728 1-415-667-7000 Copyright © 2020 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM N-CSR CERTIFIED SHAREHOLDER REPORT OF REGISTERED MANAGEMENT INVESTMENT COMPANIES Investment Company Act file number: 811-22311 Schwab Strategic Trust Schwab U.S. Equity ETFs and Schwab International Equity ETFs (Exact name of registrant as specified in charter) 211 Main Street, San Francisco, California 94105 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Jonathan de St. Paer Schwab Strategic Trust Schwab U.S. Equity ETFs and Schwab International Equity ETFs 211 Main Street, San Francisco, California 94105 (Name and address of agent for service) Registrants telephone number, including area code: (415) 636-7000 Date of fiscal year end: August 31 Date of reporting period: August 31, 2020 Item 1: Report(s) to Shareholders. Copyright © 2020 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. -

Becoming a Substantial Holder from MUFG

Form 603 Corporations Act 2001 Section 671B Notice of initial substantial holder To Company Name/Scheme CYCLOPHARM LIMITED ACN/ARSN 116 931 250 … 1. Details of substantial holder (1) Name Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, Inc. ACN/ARSN (if applicable) Not Applicable The holder became a substantial holder on 12 April 2021 The holder became aware on 14 April 2021 2. Details of voting power The total number of votes attached to all the voting shares in the company or voting interests in the scheme that the substantial holder or an associate (2) had a relevant interest (3) in on the date the substantial holder became a substantial holder are as follows: Class of securities (4) Number of securities Person’s votes (5) Voting power (6) Fully Paid Ordinary Shares 5,072,944 5,072,944 5.43% 3. Details of relevant interests The nature of the relevant interest the substantial holder or an associate had in the following voting securities on the date the substantial holder became a substantial holder are as follows: Class and number Holder of relevant interest Nature of relevant interest (7) of securities Relevant interest in securities that Morgan Stanley has a relevant interest in Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, 5,068,575 Ordinary under section 608(3) of the Corporations Act as Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Inc. Shares Group, Inc. has voting power of over 20% in Morgan Stanley. Relevant interest in securities that Morgan Stanley has a relevant interest in Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, under section 608(3) of the Corporations Act as Mitsubishi UFJ Financial 1,268 Ordinary Shares Inc. -

Companies That Match Gifts a Advanced Micro Devices Advantis

Companies that Match Gifts Amgen Berkeley Systems, Inc. A Anchor Brewing Co. Best Foods Advanced Micro Devices Antioch Companies/Webway BF Goodrich Co. Advantis AOL Time Warner Birkenstock Footprint Sandals AES Corp. AON Fdn. Bixby Land Co. Aetna Fdn., Inc. Apple Black and Decker AGIA, Inc. Applied Materials Blandin Fdn. Agilent Technologies Aramark Corp. Blauvelt Demarest Fdn., Inc. Agribank, FCB Archer-Daniels-Midland Co. Bloomingdale's Air Products & Chemicals Inc. Archie, Bertha Walker Fdn. Blount Fdn. Alex Brown & Sons, Inc. ARCO Fdn. Blue Shield of California Alexander & Baldwin Fdn. Argonaut Insurance Group BMC Industries Inc. Allendale Mutual Insurance Arkwright Fdn., Inc. BNSF Alliance Capital Management Arthur J. Gallagher Fdn. Boeing Co. Alliant Techsystems Inc. Aspect Communications Boeing Gift Matching Program Allied Signal Inc. Aspect Global Giving Program/ Boole & Babbage, Inc. Allstate Giving Campaign Aspect Telecommunications Booz Allen Hamilton Allstate Insurance Co. AT&T Fdn. Borden Fdn. Altria ATC Boston Consulting Group ALZA Corp. ATK Sporting Equipment BP Amoco Corp. American Cynamid Autodesk, Inc. BP Fdn. American Express Automatic Data Processing Braun Intertec Co. American Honda Motor Co. Aventis Pharmaceuticals Breslauer and Rutman, LLC American International Group Avery Dennison Brobeck Charitable Fdn. (AIG) Avon Broderbund Fdn. American Management Axa Fdn. BT Commercial/Deutsche Bank Systems, Inc. Ayco BTD Manufacturing, Inc. Ameriprise Financial B BTW Consultants, Inc. Ameritech Corp. Barclays Burlington Northern Santa Fe Ameron Inc. Bemis Co. Fdn. Railway Co. Business Wire Butler Manufacturing Co. CAN Fdn. CNA Insurance Co. Fdn. Bakar, Gerson Fdn. Candle Fdn. CNA Surety Co. Bakers Square Restaurants Capital Group Companies Coca-Cola Fdn. Bank of America Carnegie Fdn. -

List of Marginable Otc Stocks1 List of Foreign

LIST OF MARGINABLE OTC STOCKS 1 AND LIST OF FOREIGN MARGIN STOCKS 2 AS OF November 10, 1997 The List of Marginable OTC Stocks and the List of Foreign Margin Stocks are published quarterly by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (the Board). The List of Marginable OTC Stocks is composed of stocks traded in the United States over-the-counter (OTC) that have been determined by the Board to be subject to margin requirements as of November 10, 1997, pursuant to Section 207.6 of Federal Reserve Regulation G, ‘‘Securities Credit by Persons Other Than Banks, Brokers, or Dealers,’’ Section 220.17 of Regulation T, ‘‘Credit by Brokers and Dealers,’’ and Section 221.7 of Regulation U, ‘‘Credit by Banks for the Purpose of Purchasing or Carrying Margin Stocks.’’ It also includes all OTC stocks designated as National Market System (NMS) securities. Additional NMS securities may be added in the interim between Board quarterly publications; these securities are immediately marginable upon designation as NMS securities. The names of these securities are available at the National Association of Securities Dealers, Inc. and at the Securities and Exchange Commission. This List supersedes the previous List of Marginable OTC Stocks published effective August 11, 1997. The List of Foreign Margin Stocks is composed of foreign equity securities that have met the Board’s eligibility criteria, pursuant to Regulation T, Section 220.17. These foreign equity securities are eligible for margin treatment at broker–dealers on the same basis as domestic margin securities. This list supersedes the previous List of Foreign Margin Stocks published effective August 11, 1997.