Shushtar New Town: the Idea of a Community Interview with KAMRAN DIBA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

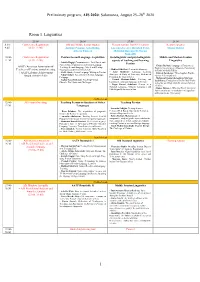

Preliminary Program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28Th 2020

Preliminary program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28th 2020 Room 1. Linguistics 25.08 26.08 27.08 28.08 8:30- Conference Registration Old and Middle Iranian studies Plenary session: Iran-EU relations Keynote speaker 9:45 (8:30–12:00) Antonio Panaino, Götz König, Luciano Zaccara, Rouzbeh Parsi, Maziar Bahari Alberto Cantera Mehrdad Boroujerdi, Narges Bajaoghli 10:00- Conference Registration Persian Second Language Acquisition Sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic Middle and Modern Iranian 11:30 (8:30–12:00) aspects of teaching and learning Linguistics - Latifeh Hagigi: Communicative, Task-Based, and Persian Content-Based Approaches to Persian Language - Chiara Barbati: Language of Paratexts as AATP (American Association of Teaching: Second Language, Mixed and Heritage Tool for Investigating a Monastic Community - Mahbod Ghaffari: Persian Interlanguage Teachers of Persian) annual meeting Classrooms at the University Level in Early Medieval Turfan - Azita Mokhtari: Language Learning + AATP Lifetime Achievement - Ali R. Abasi: Second Language Writing in Persian - Zohreh Zarshenas: Three Sogdian Words ( Strategies: A Study of University Students of (m and ryżי k .kי rγsי β יי Nahal Akbari: Assessment in Persian Language - Award (10:00–13:00) Persian in the United States Pedagogy - Mahmoud Jaafari-Dehaghi & Maryam - Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi: Teaching and - Asghar Seyed-Ghorab: Teaching Persian Izadi Parsa: Evaluation of the Prefixed Verbs learning the formulaic language in Persian Ghazals: The Merits and Challenges in the Ma’ani Kitab Allah Ta’ala -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 07 April 2008 Version of attached file: Published Version Peer-review status of attached file: Unknown Citation for published item: Seccombe, I. and Lawless, R. (1987) ’Work camps and company towns : settlement patterns and the Gulf oil industry.’, Working Paper. University of Durham, Centre for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, Durham. Further information on publisher’s website: http://www.dur.ac.uk/sgia/ Publisher’s copyright statement: Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 — Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 http://dro.dur.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM CENTRE FOR /dIDDLE EASTERN A NO ISLAMIC STUDIES Work Camps and Company Towns: Settlement Patterns and the Gulf Oil Industry r~~;':'SH UCR:. 'J,y~~< TS!. 'Ply CENTr.E : -'.';i.:t tf' I • .1 J. ~ .~ I ... Ian Seccomhe aod 'Rfclrard,L",Ies I ~ ... .. "_, _ •• ..I';;- vrj'.. ; 1""8'-.(:J -··•• , C"o_..... 1=5 Occasional Papers Series No. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 07 April 2008 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Unknown Citation for published item: Seccombe, I. and Lawless, R. (1987) 'Work camps and company towns : settlement patterns and the Gulf oil industry.', Working Paper. University of Durham, Centre for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, Durham. Further information on publisher's website: http://www.dur.ac.uk/sgia/ Publisher's copyright statement: Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM CENTRE FOR /dIDDLE EASTERN A NO ISLAMIC STUDIES Work Camps and Company Towns: Settlement Patterns and the Gulf Oil Industry r~~;':'SH UCR:. 'J,y~~< TS!. 'Ply CENTr.E : -'.';i.:t tf' I • .1 J. ~ .~ I ... Ian Seccomhe aod 'Rfclrard,L",Ies I ~ ... .. "_, _ •• ..I';;- vrj'.. ; 1""8'-.(:J -··•• , C"o_..... 1=5 Occasional Papers Series No. -

State and Tribes in Persia 1919-1925

State and Tribes in Persia 1919-1925 A case study On Political Role of the Great Tribes in Southern Persia Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie (Dr. Phil.) Freie Universität Berlin Otto-Suhr-Institut für Politikwissenschaften Fachbereich Politik- und Sozialwissenschaften vorgelegt von: Javad Karandish Berlin, Januar 2003 Published 2011 1 1. Erstgutachter: Herr Prof. Dr. Wolf-Dieter Narr 2. Zweitgutachter: Herr Prof. Dr. Friedemann Büttner Disputationsdatum: 18.11.2003 2 PART I: GENERAL BACKGROUND ............................................................................................. 11 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 12 1. THE STATEMENT OF A PROBLEM .......................................................................................... 12 1.1. Persia After the War.............................................................................................................. 15 2. THE RELEVANT QUESTIONINGS ............................................................................................. 16 3. THEORETICAL BASIS............................................................................................................. 17 4. THE METHOD OF RESEARCH .................................................................................................. 20 5. THE SUBJECT OF DISCUSSION ............................................................................................... -

Characteristics of Direct Human Impacts on the Rivers Karun and Dez in Lowland South-West Iran and Their Interactions with Earth Surface Movements

© 2016, Elsevier. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Characteristics of direct human impacts on the rivers Karun and Dez in lowland south-west Iran and their interactions with earth surface movements Kevin P. Woodbridge, Daniel R. Parsons, Vanessa M. A. Heyvaert, Jan Walstra, Lynne E. Frostick Abstract Two of the primary external factors influencing the variability of major river systems, over river reach scales, are human activities and tectonics. Based on the rivers Karun and Dez in south-west Iran, this paper presents an analysis of the geomorphological responses of these major rivers to ancient human modifications and tectonics. Direct human modifications can be distinguished by both modern constructions and ancient remnants of former constructions that can leave a subtle legacy in a suite of river characteristics. For example, the ruins of major dams are characterised by a legacy of channel widening to 100's up to c. 1000 m within upstream zones that can stretch to channel distances of many kilometres upstream of former dam sites, whilst the legacy of major, ancient, anthropogenic river channel straightening can also be distinguished by very low channel sinuosities over long lengths of the river course. Tectonic movements in the region are mainly associated with young and emerging folds with NW–SE and N–S trends and with a long structural lineament oriented E–W. These earth surface movements can be shown to interact with both modern and ancient human impacts over similar timescales, with the types of modification and earth surface motion being distinguishable. -

Download the Entire 2015-2016 Annual Report In

THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE 2015–2016 ANNUAL REPORT © 2016 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2016. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago ISBN: 978-1-61491-035-0 Editor: Gil J. Stein Production facilitated by Emily Smith, Editorial Assistant, Publications Office Cover and overleaf illustration: Eastern stairway relief and columns of the Apadana at Persepolis. Herzfeld Expedition, 1933 (D. 13302) The pages that divide the sections of this year’s report feature images from the special exhibit “Persepolis: Images of an Empire,” on view in the Marshall and Doris Holleb Family Gallery for Special Exhibits, October 11, 2015, through September 3, 2017. See Ernst E. Herzfeld and Erich F. Schmidt, directors of the Oriental Institute’s archaeological expedition to Persepolis, on page 10. Printed by King Printing Company, Inc., Lowell, Massachusetts, USA CONTENTS CONTENTS INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION. Gil J. Stein ........................................................ 5 IN MEMORIAM . 7 RESEARCH PROJECT REPORTS ÇADıR HÖYÜK . Gregory McMahon ............................................................ 13 CENTER FOR ANciENT MıDDLE EASTERN LANDSCAPES (CAMEL) . Emily Hammer ........................ 18 ChicAGO DEMOTic DicTıONARY (CDD) . Janet H. Johnson .......................................... 28 ChicAGO HıTTıTE AND ELECTRONic HıTTıTE DicTıONARY (CHD AND eCHD) . Theo van den Hout ........... 33 DENDARA . Gregory Marouard................................................................ 35 EASTERN -

Historical Lateral Irrigation Facilities and Water-Related Technologies in Shushtar and Dezful-Mill, Dungeon, Gyre, Waterwheel Pjaee, 18 (8) (2021)

HISTORICAL LATERAL IRRIGATION FACILITIES AND WATER-RELATED TECHNOLOGIES IN SHUSHTAR AND DEZFUL-MILL, DUNGEON, GYRE, WATERWHEEL PJAEE, 18 (8) (2021) HISTORICAL LATERAL IRRIGATION FACILITIES AND WATER-RELATED TECHNOLOGIES IN SHUSHTAR AND DEZFUL-MILL, DUNGEON, GYRE, WATERWHEEL Parviz Talaeyanpour1*, Hossein Moftakhari2, Mirhadi Hosseini3 1*,2,3Department of History, Faculty of Literature and Humanities, Kharazmi University, Tehran, Iran. Corresponding Author: 1*[email protected] Parviz Talaeyanpour, Hossein Moftakhari, Mirhadi Hosseini. Historical Lateral Irrigation Facilities and Water-Related Technologies in Shushtar and Dezful-Mill, Dungeon, Gyre, Waterwheel-- Palarch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology 18(8), 3265-3273. ISSN 1567-214x Keywords: Shushtar Mills, Dezul Mills, Dungeon. Abstract According to various studies and researchers mills originate in Iran. Due to enjoying several rivers and five large streams in this part of the country, this technology has been used for making wheat flour since ancient times in the province of Khuzestan. Since the Sassanid Empire, historical cities such as Shushtar and Dezful have utilized the energy of water for a variety of purposes such as constructing numerous mills in these two counties due to their two large rivers, i.e. Karun and Dez. The greatest number of mills in Iran, either great in number or size, are located in this county, which resulted in creating a great industrial complex. After Shushtar, the second largest collection of mills of the country, either in terms of number or the technology (indirect energy transmission), is located in Dezful. Dungeon and Gyre are two techniques for water transmission that are used for irrigation and supplying water, which has been used for a long period of time in Iran. -

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

IAJPS 2017, 4 (11), 4243-4251 Hamid Kassiri et al ISSN 2349-7750 CODEN [USA]: IAJPBB ISSN: 2349-7750 INDO AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHARMACEUTICAL SCIENCES Available online at: http://www.iajps.com Research Article CUTANEOUS LEISHMANIASIS: EVALUATION OF 248 CASES IN SHUSHTAR COUNTY, SOUTH-WEST OF IRAN Hamid Kassiri * 1, Parvaneh Farajifard 2 1 School of Health, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran 2 Student Research Committee, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran Abstract: Objectives: leishmaniasis is one of six major tropical diseases that the World Health Organization has supported study and research about various aspects of the recommendations. Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is considered a common parasitic disease. This study was performed to determine the frequency of patients with CL and the epidemiological situation in the county of Shushtar during 2009- 2013. Methods: In this descriptive study, information about subjects such as age, gender , number and location of wounds , city or village , month and season collected and have been interpreted with SPSS software and descriptive statistics. Results: Totally, 248 cases have detected during this study. About 82.7 percent percent of patients had more than 10 years of age and most cases (66.1 percent) were found in males. Nearly 48.4 percent of patients had one ulcer and 37.1 percentage of the wounds were observed on the hands and then in feet, face and in other parts of the body. Approximately 83.9 percent were in rural areas and most cases were in March month (16.9 percent). Conclusions: According to the environmental conditions for sand fly activity in some months in this area prevention and treatment of patients in urban and rural areas of Shushtar is a key priority. -

Podoces 2 2 Western Travellers in Iran-2

Podoces, 2007, 2(2): 77–96 A Century of Breeding Bird Assessment by Western Travellers in Iran, 1876–1977 1 1,2 C. S. (KEES) ROSELAAR * & MANSOUR ALIABADIAN 1. Zoological Museum & Institute of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics, University of Amsterdam PO Box 94766, 1090 GT Amsterdam, the Netherlands 2. Faculty of Science, Department of Biology, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran * Correspondence Author. Email: [email protected] Received 14 June 2007; accepted 1 December 2007 Abstract: This article lists 99 articles on distribution of wild birds in Iran, which appeared between 1876 and 1977 and which were published by authors writing in European languages. Each paper has a reference number and is supplied with annotations, giving the localities and time of year where the bird observations had been made. These localities are also listed on a separate website (www.wesca.net/podoces/podoces.html), supplied with coordinates and the reference number. With help of these coordinates and the original publications an historical atlas of bird distribution in Iran can be made. A few preliminary examples of such maps are included. Many authors also collected bird specimens in Iran, either to support their identifications or in order to enravel subspecies taxonomy of the birds of Iran. The more important natural history museums containing study specimens from Iran are listed. Keywords: Iran, Zarudnyi, Koelz, birds, gazetteer, literature, Passer, Podoces, Sitta . ﻣﻘﺎﻟﻪ ﺣﺎﺿﺮ ﺑﻪ ﺷﺮﺡ ﻣﺨﺘﺼﺮﻱ ﺍﺯ ﻣﻜﺎ ﻥﻫﺎ ﻭ ﺯﻣﺎ ﻥ ﻫﺎﻱ ﻣﺸﺎﻫﺪﻩ ﭘﺮﻧﺪﮔﺎﻥ ﺍﻳﺮﺍﻥ ﺑﺮ ﺍﺳﺎﺱ ۹۹ ﻣﻘﺎﻟﻪ ﺍﺯ ﭘﺮﻧﺪﻩﺷﻨﺎﺳـﺎﻥ ﺍﺭﻭﭘـﺎﻳﻲ ﺩﺭ ﺑـﻴﻦ ﺳـــﺎﻝ ﻫـــﺎﻱ ۱۸۷۶ ﺗـــﺎ ۱۹۷۷ ﻣـــﻲ ﭘـــﺮﺩﺍﺯﺩ ﻛـــﻪﻣﺨﺘـــﺼﺎﺕ ﺟﻐﺮﺍﻓﻴـــﺎﻳﻲ ﺍﻳـــﻦ ﻣﻜـــﺎ ﻥﻫـــﺎ ﻗﺎﺑـــﻞ ﺩﺳﺘﺮﺳـــﻲ ﺩﺭ ﺁﺩﺭﺱ www.wesca.net/podoces/podoces.html ﻣ ﻲ ﺑﺎﺷﺪ . -

Epidemiological Survey on Scorpionism in Gotvand County

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Journal of Acute Disease (2014)314-319 314 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Acute Disease journal homepage: www.jadweb.org Document heading doi: 10.1016/S2221-6189(14)60067-6 Epidemiological survey on scorpionism in Gotvand County, Southwestern Iran: an analysis of 1 067 patients Hamid Kassiri1*, Elnaz Kassiri2, Rahele Veys-Behbahani1, Ali Kassiri3 1Health School, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran 2Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran 3Medicine School, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Objective: To study epidemiologic parameters of scorpion stings in Gotvand County, Received 8 August 2013 Methods: Southwestern Iran, during 2006-2008. In this descriptive study, data were collected Received in revised form 15 September 2013 G C A Accepted 24 September 2013 from health services center's files at otvand ounty. special scorpion sting sheet was T Available online 20 November 2014 prepared. his sheet contained information about the site of scorpion stung, the date and place of the accident, the sex of the injured and etc. TheResults: frequencies of entomo-epidemiological Keywords: characters were changed to the percentage basis. Cases were collected from health Scorpion sting services center's files over three years. There were 1 067 scorpion victims, 44.1% of whom were Epidemiology from rural areas. Stings occurred throughout the year, however, the highest and lowest frequency Incidence rate happened in August (12.5%), January (1.9%) and February (1.9%), respectively. -

Ethical Sustainability in Iranian New Towns: Case Study of Shushtar New Town

Asian Social Science; Vol. 10, No. 13; 2014 ISSN 1911-2017 E-ISSN 1911-2025 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Ethical Sustainability in Iranian New Towns: Case Study of Shushtar New Town Mahdi Hamzenazhad1, Mohadeseh Mahmoudi2 & Bushra Abbasi1 1 School of Architecture and Environmental Design, Iran University of Science and Technology, Islamic Republic of Iran 2 Faculty of Design and Architecture, University Putra Malaysia, Malaysia Correspondence: Mohadeseh Mahmoudi, Faculty of Design and Architecture, University Putra Malaysia, Malaysia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: May 5, 2014 Accepted: May 19, 2014 Online Published: June 25, 2014 doi:10.5539/ass.v10n13p252 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v10n13p252 Abstract Shushtar is ancient city in Khuzestan Province at south west of Iran and is considered as a world heritage. In the early 70’s, Shushtar New Town was decided to be constructed in order to answer the residential needs on new employers of Karun Agro-Industries Corporation. The project was located across the river from the old city and Kamran Diba, an Iranian well-known architect, designed this New Town for 30,000 residents. Shushtar New Town was designed in relevant with the cultural values of Iranian civilization to maintain the continuity with its regional historical background. Architect’s high attention on the traditional, cultural, social and historical aspect of the project helped it to be introduced as the distinguish design of 20th century. Yet, how was ethical sustainability emanated in the master plan of Shushtar New Town? This research aims to examine sustainability in the design priorities and current condition of Shushtar New Town, on the basis of ethical sustainability as the most integrated and comprehensive current approach of sustainable development. -

Investigating Fold-River Interactions for Major Rivers Using a Scheme of Remotely Sensed Characteristics of River and Fold Geomorphology

remote sensing Article Investigating Fold-River Interactions for Major Rivers Using a Scheme of Remotely Sensed Characteristics of River and Fold Geomorphology Kevin P. Woodbridge 1, Saied Pirasteh 2,* and Daniel R. Parsons 1 1 Energy and Environment Institute, Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Hull, Cottingham Road, Hull HU6 7RX, UK 2 Department of Surveying and Geoinformatics, Faculty of Geosciences and Environmental Engineering (FGEE), Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu 611756, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-1318-3819-193 Received: 10 July 2019; Accepted: 24 August 2019; Published: 29 August 2019 Abstract: There are frequently interactions between active folds and major rivers (mean annual water 3 1 discharges > 70 m s− ). The major river may incise across the fold, to produce a water gap across the fold, or a bevelling (or lateral planation) of the top of the fold. Alternatively, the major river may be defeated to produce a diversion of the river around the fold, with wind gaps forming across the fold in some cases, or ponding of the river behind the fold. Why a river incises or diverts is often unclear, though influential characteristics and processes have been identified. A new scheme for investigating fold-river interactions has been devised, involving a short description of the major river, climate, and structural geology, and 13 characteristics of river and fold geomorphology: (1) Channel width at location of fold axis, w, (2) Channel-belt width at location of fold axis, cbw, (3)