African States and the Universal Periodic Review Mechanism: a Study of Effectiveness and the Potential for Acculturation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dear Students As a Busy Year Draws to a Close, We'd Like to Provide You

DEPARTMENT OF From 13 to 15 July, the Department, together POLITICAL SCIENCES with the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation and NEWSLETTER the Embassy of Sweden, hosted a seminar November 2011 on the “United Nations and Regional Challenges in Africa: 50 years after the death of Dag Hammarskjöld”. The event was Dear students opened by Ms Graça Machel , and speakers included former UN Special Envoy Jan As a busy year draws to a close, we’d like to Pronk , Dr Monica Juma , Kenya’s Ambas- provide you with an overview of events and sador to the AU, and the Kofi Annan Inter- goings-on in the Department of Political national Peacekeeping Training Centre’s Dr Sciences this semester. Kwesi Aning . The Department’s Dr Henning Melber delivered the keynote address, “Dag Our newsletter also affords us the opportunity Hammarskjöld: Ethics, solidarity and global to thank you for your participation in leadership”; Mr Jan Mutton chaired the Departmental events, and to acknowledge opening panel discussion; Professor Laurie your support and enthusiasm. Nathan presented a paper on “The SADC Tribunal: regional organisations, human security, human rights and international law”; HIGHLIGHTS OF THE SEMESTER and Professor Sandy Africa participated in the final round-table discussion on “Africa and global governance: international perspectives for peace, security and the rule of law”. On 15 September, Mr Ebrahim Ebrahim , Deputy Minister of International Relations and Cooperation led a panel discussion on the topic “Libya, the United Nations, the African Union and South Africa: Wrong moves? Wrong motives?” The event was co-hosted by the Department, the Centre for Mediation in Africa and the Centre for Human Rights, and sponsored by the Open Society Foun- On 13 October, South African President dation for South Africa. -

Covid-19 Social Relief of Distress Grant

Thursday, 7 May 2020 President Cyril Ramaphosa His Excellency, President Cyril Ramaphosa, President of the Republic of South Africa Copied to: MINISTER OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT Ms Lindiwe Zulu c/o Ms Zama Kumalo; Ms Monica Zabo; Ms Lumka Olifant MINISTER OF WOMEN, YOUTH AND PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES Minister Maite Nkoana-Mashabane Private Secretary: Ms Mantikwe Ramokgopa Ms Millie Ramoraswi Chief of Staff Acting Director General (ADG): MS. W.R. (Shoki) Tshabalala MINISTER OF EMPLOYMENT AND LABOUR Minister Thembelani Thulas Nxesi DEPUTY MINISTER BOITUMELO ELIZABETH MOLOI UIF Chief Operations Officer: Ms Judith Kumbi MINISTER OF FINANCE Minister Tito Mboweni Office of the Director General Dondo Mogajane DDG: Public Finance Acting DDG: Budget Office DDG: Public Finance Mampho Modise 1 Dear President Ramaphosa, RE: COVID-19 SOCIAL RELIEF OF DISTRESS GRANT Introduction We note government’s emergency economic and social relief measures to alleviate the impact of the COVID- 19 pandemic and the resulting nationwide lockdown on individuals and households. While the relief measures are a small step in the right direction, they are insufficient to meet the current humanitarian crisis under lockdown conditions. Many poor families are going hungry. The situation remains desperate with many queueing for food parcels. The threat of starvation or even the possibility of death from hunger, rather than from the coronavirus, for many people is real.1 It is within this context that we argue that the social grant relief measures remain inadequate. COVID-19 has underscored the critical role of adequate investments in public health, comprehensive social protection programmes, dignified and decent work, and access to food, water, sanitations systems and housing. -

When Elephants Fight

WH Electoral violence has scarred the momentous steps Africa has made in the transition from authoritarianism and despotism since the countries of the E continent began to gain their independence some 50 years ago. When Elephants N Fight chronicles contemporary trends and examines electoral conflicts and the WHEN way in which various national, regional, and international players have tried to E resolve them. The title of the book captures the point that when political parties L E and power elites battle for power it is the ordinary people who suffer most, some PHANT losing their lives, others their homes and livelihoods. The volume brings together ELEPHANTS academics and practitioners in a unique exercise aimed at shedding light on one of the most pressing contemporary issues in African politics – the need to stem the tide of electoral conflict and violence. The primary thesis is that as Africa undergoes yet another great transformation S FIGHT since independence we should learn from the institutional flaws that have FI produced electoral violence and transcend them by constitutional and electoral PREVENTING AND RESOLVING engineering. G In addition to detailed case studies of Kenya, Lesotho, Nigeria, Tanzania, HT ELECTION-RELATED CONFLICTS and Zimbabwe, the book focuses on the role of regional African institutions in contributing to the principles and guidelines aimed at promoting orderly and IN AFRICA peaceful political competition and the constitutional transfer of power. When Elephants Fight highlights the importance of building solid political, | Matlosa Khadiagala Shale Edited by constitutional and electoral systems that will underpin Africa’s democracy. The authors recognise that while institutions, systems, rules and regulations matter in the conduct of politics so too do the political culture and behaviour of political parties and power elites. -

Cultural Understandings and Lived Realities of Entrepreneurship In

Cultural Understandings and Lived Realities of Entrepreneurship in Post-Apartheid South Africa by Melissa Beresford A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved September 2018 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Amber Wutich, Chair H. Russell Bernard Takeyuki Tsuda Abigail York ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2018 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines cultural understandings and lived realities of entrepreneurship across South Africa’s economic landscape, comparing the experiences of Cape Town’s Black entrepreneurs in under-resourced townships to those of White entrepreneurs in the wealthy, high finance business district. Based on 13 months of participant observation and interviews with 60 entrepreneurs, I find major differences between these groups of entrepreneurs, which I explain in three independent analyses that together form this dissertation. The first analysis examines the entrepreneurial motivations of Black entrepreneurs in Khayelitsha, Cape Town’s largest township. This analysis gives insight into expressed cultural values of entrepreneurship beyond a priori neoliberal analytical frameworks. The second analysis compares the material resources that Black entrepreneurs in Khayelitsha and White entrepreneurs in downtown Cape Town require for their businesses, and the mechanisms through which they secure these resources. This analysis demonstrates how historical structures of economic inequality affect entrepreneurial strategies. The third analysis assesses the non-material obstacles and challenges that both Black entrepreneurs in Khayelitsha and White entrepreneurs in wealthy areas of downtown Cape Town face in initiating their business ventures. This analysis highlights the importance of cultural capital to entrepreneurship and explains how non-material obstacles differ for entrepreneurs in different positions of societal power. -

The New Cabinet

Response May 30th 2019 The New Cabinet President Cyril Ramaphosa’s cabinet contains quite a number of bold and unexpected appointments, and he has certainly shifted the balance in favour of female and younger politicians. At the same time, a large number of mediocre ministers have survived, or been moved sideways, while some of the most experienced ones have been discarded. It is significant that the head of the ANC Women’s League, Bathabile Dlamini, has been left out – the fact that her powerful position within the party was not enough to keep her in cabinet may be indicative of the President’s growing strength. She joins another Zuma loyalist, Nomvula Mokonyane, on the sidelines, but other strong Zuma supporters have survived. Lindiwe Zulu, for example, achieved nothing of note in five years as Minister of Small Business Development, but has now been given the crucial portfolio of social development; and Nathi Mthethwa has been given sports in addition to arts and culture. The inclusion of Patricia de Lille was unforeseen, and it will be fascinating to see how, as one of the more outspokenly critical opposition figures, she works within the framework of shared cabinet responsibility. Ms de Lille has shown herself willing to change parties on a regular basis and this appointment may presage her absorbtion into the ANC. On the other hand, it may also signal an intention to experiment with a more inclusive model of government, reminiscent of the ‘government of national unity’ that Nelson Mandela favoured. During her time as Mayor of Cape Town Ms de Lille emphasised issues of spatial planning and land-use, and this may have prompted Mr Ramaphosa to entrust her with management of the Department of Public Works’ massive land and property holdings. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Revisiting the Goldenberg Ghosts,Knowing

Remembering Zindzi, the Other Mandela By Isaac Otidi Amuke On 10 February 1985, the world’s attention was drawn to the courageous defiance of 25-year- old Zindzi Mandela, the youngest of two daughters born to political prisoner Nelson Mandela and anti- apartheid revolutionary Winnie Madikizela-Mandela. The occasion was a rally at Soweto’s Jabulani Stadium organised by the anti-apartheid caucus, the United Democratic Front (UDF), to celebrate the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Johannesburg’s Bishop Desmond Tutu. In the absence of her parents (Mandela in jail and Madikizela-Mandela banned and banished in Brandfort) anti- apartheid stalwart Albertina Sisulu took the role of guardian, standing next to Zindzi. Zindzi sang, danced and occasionally punched her clenched fist into the air to chants of Amandla!, before reading her father’s historic letter to the nation. Apartheid South Africa’s President P.W. Botha had used prison back channels to offer Mandela the option of an early conditional release, having served two decades. In declining Botha’s overtures, Mandela sought to respond through a public communique, hence his decision to deploy Zindzi to the front lines. Zindzi did not disappoint. Having grown into her own as an activist and witness to the barbarism the apartheid state had unleashed on Black South Africans, and especially on the Mandela–Madikizela- Mandela family, Zindzi powerfully delivered the nine-minute message, which was punctuated by recurring recitals of ‘‘my father and his comrades”. Her chosen refrain meant that Zindzi wasn’t only relaying Mandela’s words, but was also speaking on behalf of tens of political prisoners who lacked a medium through which to engage the masses. -

South Africa in Africa the Post-Apartheid Decade

Un Report Cover 5 11/8/04 3:09 PM Page 2 FOUNDATION FOR HUMAN RIGHTS DEZA DDC DSC SDC COSUDE SOUTH AFRICAIN DANIDA EMBASSY OF FINLAND DECADE THE POST-APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA IN AFRICA THE POST-APARTHEID DECADE ies Afr d ica tu n S C c i AC e g D n e E t t r S e a r S t UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN f o S r d D n e a v e C/O RHODES GIFT POST OFFICE, RONDEBOSCH, 7707 t l n o e p m TEL: +27 21 422 2512 FAX: +27 21 422 2622 E-MAIL: [email protected] Home page: http://ccrweb.ccr.uct.ac.za/ SEMINAR REPORT STELLENBOSCH, SOUTH AFRICA 29 JULY - 1 AUGUST 2004. RAPPORTEURS: CHERYL HENDRICKS AND KAYE WHITEMAN NOVEMBER 2004 SA In Africa 200x270 Q6 11/8/04 2:44 PM Page 1 SOUTH AFRICA IN AFRICA THE POST-APARTHEID DECADE SEMINAR REPORT STELLENBOSCH, SOUTH AFRICA, 29 JULY - 1 AUGUST 2004 RAPPORTEURS: CHERYL HENDRICKS AND KAYE WHITEMAN NOVEMBER 2004 ies Afr d ica tu n S C c i AC e g D n e E t t r S e a r S t f o S r d D n e a v e t l n o e p m African Centre for Development and Centre for Policy Studies Strategic Studies SOUTH AFRICA IN AFRICA: THE POST-APARTHEID DECADE 1 SA In Africa 200x270 Q6 11/8/04 2:44 PM Page 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 About the Organisers 3 About the Rapporteurs 3 Executive Summary 4 Introduction 10 1. -

LIST of MEMBERS (Female)

As on 28 May 2021 LIST OF MEMBERS (Female) 6th Parliament CABINET OFFICE-BEARERS OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY MEMBERS OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY As on 28 May 2021 MEMBERS OF THE EXECUTIVE (alphabetical list) Minister of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development ............. Ms A T Didiza Minister of Basic Education ....................................................... Mrs M A Motshekga Minister of Communications and Digital Technologies ....................... Ms S T Ndabeni-Abrahams Minister of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs ............... Dr N C Dlamini-Zuma Minister of Defence and Military Veterans ..................................... Ms N N Mapisa-Nqakula Minister of Forestry, Fisheries and Environment ............................... Ms B D Creecy Minister of Human Settlements, Water and Sanitation ...................... Ms L N Sisulu Minister of International Relations and Cooperation ......................... Dr G N M Pandor Minister of Public Works and Infrastructure ................................... Ms P De Lille Minister of Small Business Development ....................................... Ms K P S Ntshavheni Minister of Social Development .................................................. Ms L D Zulu Minister of State Security ......................................................... Ms A Dlodlo Minister of Tourism ................................................................. Ms M T Kubayi-Ngubane Minister in The Presidency for Women, Youth and Persons with Disabilities ..................................................................... -

Report of the 54Th National Conference Report of the 54Th National Conference

REPORT OF THE 54TH NATIONAL CONFERENCE REPORT OF THE 54TH NATIONAL CONFERENCE CONTENTS 1. Introduction by the Secretary General 1 2. Credentials Report 2 3. National Executive Committee 9 a. Officials b. NEC 4. Declaration of the 54th National Conference 11 5. Resolutions a. Organisational Renewal 13 b. Communications and the Battle of Ideas 23 c. Economic Transformation 30 d. Education, Health and Science & Technology 35 e. Legislature and Governance 42 f. International Relations 53 g. Social Transformation 63 h. Peace and Stability 70 i. Finance and Fundraising 77 6. Closing Address by the President 80 REPORT OF THE 54TH NATIONAL CONFERENCE 1 INTRODUCTION BY THE SECRETARY GENERAL COMRADE ACE MAGASHULE The 54th National Conference was convened under improves economic growth and meaningfully addresses the theme of “Remember Tambo: Towards inequality and unemployment. Unity, Renewal and Radical Socio-economic Transformation” and presented cadres of Conference reaffirmed the ANC’s commitment to our movement with a concrete opportunity for nation-building and directed all ANC structures to introspection, self-criticism and renewal. develop specific programmmes to build non-racialism and non-sexism. It further directed that every ANC The ANC can unequivocally and proudly say that we cadre must become activists in their communities and emerged from this conference invigorated and renewed drive programmes against the abuse of drugs and to continue serving the people of South Africa. alcohol, gender based violence and other social ills. Fundamentally, Conference directed every ANC We took fundamental resolutions aimed at radically member to work tirelessly for the renewal of our transforming the lives of the people for the better and organisation and to build unity across all structures. -

NEWSLETTER December 2020

NEWSLETTER December 2020 Launch of the Emergency Appeal for COVID-19 Response in South Africa Ms. Nardos Bekele-Thomas, the Resident Coordinator of the United Nations in South Africa commended the Government’s commitment to a whole-of-society and a whole-of-government approach to the COVID-19 response. Echoing the words of the United Nations Secretary-General, Mr. Antonio Guterres, the Resident Coordinator noted that ‘this moment demands coordinated, decisive, and innovative policy action from the world’s leading economies, recognizing that the poorest countries and most vulnerable, especially women, will be the hardest hit.’ Since the virus is undermining the social fabric of the country and the economy, affecting supply chains, businesses and jobs, there needs to be an emphasis on the delivery of essential services to build on pre- COVID-19 development gains, and support to the country in completing the unfinished business of the Sustainable Development Goals. The Resident Coordinator noted that she was encouraged by President Cyril Ramaphosa’s consistent message that post COVID-19 will usher in On 30 April 2020, the United Nations launched an a different model of development, focussing more on Emergency Appeal to mobilize one hundred and thirty inclusiveness, guided by the motto of leaving no one six million dollars (USD $136,000,000) to address behind. This is one of the key guiding principles of critical short-term humanitarian needs and priority the work of the United Nations, which places interventions targeting the most vulnerable emphasis on the most vulnerable, including women populations affected by COVID-19 in South Africa. -

Covid-19 Regulatory Update 25Mar2020

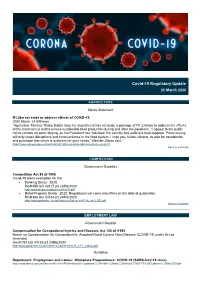

Covid-19 Regulatory Update 25 March 2020 AGRICULTURE Media Statement R1.2bn set aside to address effects of COVID-19. 2020 March 24 SANews “Agriculture Minister Thoko Didiza says her department has set aside a package of R1.2 billion to address the effects of the Coronavirus and to ensure sustainable food production during and after the pandemic. “I appeal to the public not to embark on panic buying, as the President has indicated; the country has sufficient food supplies. Panic buying will only cause disruptions and inconvenience in the food system. I urge you, fellow-citizens, to also be considerate and purchase that which is sufficient for your needs,” Minister Didiza said.” https://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/r12bn-set-aside-address-effects-covid-19 Back to Contents COMPETITION Government Gazettes Competition Act 89 of 1998 Covid-19 block exemption for the: • Banking Sector, 2020. RGN355 GG 43127 p3 23Mar2020 http://www.dti.gov.za/gazzettes/43127.pdf • Retail Property Sector, 2020: Regulations will come into effect on the date of publication. RGN358 GG 43134 p3 24Mar2020 http://www.gpwonline.co.za/Gazettes/Gazettes/43134_24-3_DTI.pdf Back to Contents EMPLOYMENT LAW Government Gazette Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act 130 of /1993 Notice on Compensation for Occupationally- Acquired Novel Corona Virus Disease (COVID-19) under Act as amended. GenN193 GG 43126 p3 23Mar2020 http://www.gpwonline.co.za/Gazettes/Gazettes/43126_23-3_Labour.pdf Guideline Department: Employment and Labour. Workplace Preparedness: COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-19 virus). http://www.labour.gov.za/DocumentCenter/Publications/Occupational%20Health%20and%20Safety/COVID-19%20Guideline%20Mar2020.pdf Covid-19 Regulatory Update: 25 March 2020 Media Statement UIF, CF safety net intervention details.