Churchill Scholarship Newsletter 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

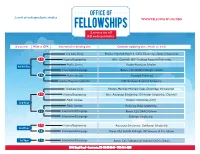

Fellowships Flowchart FA17

A unit of undergraduate studies WWW.FELLOWSHIPS.KU.EDU A service for all KU undergraduates If you are: With a GPA: Interested in funding for: Consider applying for: (details on back) Graduate Study Rhodes, Marshall, Mitchell, Gates-Cambridge, Soros, Schwarzman 3.7+ Science/Engineering Also: Churchill, NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Public Service Knight-Hennessy Scholars 4th/5th Year International/Language Boren, CLS, DAAD, Fulbright, Gilman 3.2+ Public Service Carnegie, Pickering Science/Engineering/SocSci NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Graduate Study Rhodes, Marshall, Mitchell, Gates-Cambridge, Schwarzman 3.7+ Science/Engineering Also: Astronaut Scholarship, Goldwater Scholarship, Churchill Public Service Truman Scholarship (3.5+) 3rd Year Public Service Pickering, Udall Scholarship 3.2+ International/Language Boren, CLS, DAAD, Gilman International/Language Fulbright Scholarship 3.7+ Science/Engineering Astronaut Scholarship, Goldwater Scholarship 2nd Year 3.2+ International/Language Boren, CLS, DAAD, Fulbright UK Summer, (3.5+), Gilman 1st Year 3.2+ International/Language Boren, CLS, Fulbright UK Summer, (3.5+), Gilman 1506 Engel Road • Lawrence, KS 66045-3845 • 785-864-4225 KU National Fellowship Advisors ✪ Michele Arellano Office of Study Abroad WE GUIDE STUDENTS through the process of applying for nationally and internationally Boren and Gilman competitve fellowships and scholarships. Starting with information sessions, workshops and early drafts [email protected] of essays, through application submission and interview preparation, we are here to help you succeed. ❖ Rachel Johnson Office of International Programs Fulbright Programs WWW.FELLOWSHIPS.KU.EDU [email protected] Knight-Hennessy Scholars: Full funding for graduate study at Stanford University. ★ Anne Wallen Office of Fellowships Applicants should demonstrate leadership, civic commitment, and want to join a Campus coordinator for ★ awards. -

Dartmouth College • Fellowship Advising

DARTMOUTH COLLEGE • FELLOWSHIP ADVISING NATIONAL SCHOLARSHIPS AND FELLOWSHIPS BY YEAR OF APPLICATION Sophomores Critical Language Scholarship Fulbright Summer Institute (programs at UK universities) Gilman Scholarship (study abroad programs) Goldwater Scholarship (research careers in STEM fields) Boren/NSEP Scholarship for Study Abroad Udall Scholarship (careers in the environment, Native health care, or tribal public policy) Juniors Critical Language Scholarship Gilman Scholarship (study abroad programs) Goldwater Scholarship (research careers in STEM fields) Udall Scholarship (careers in the environment, Native health care, or tribal public policy) Truman Scholarship (careers in public service) Beinecke Scholarship (graduate study in the arts, social sciences or humanities) Boren/NSEP Scholarship for Study Abroad Pickering Fellowship (careers in the Foreign Service) Seniors and Alumni Study Abroad: Rhodes Scholarship (study at Oxford) Marshall Scholarship (study in the UK) Mitchell Scholarship (study in Ireland) Fulbright Research and Teaching Assistantship (study or teaching in approx. 140 countries) Churchill Scholarship (study at Cambridge, STEM fields) DAAD Scholarship (study in Germany) Gates Cambridge Scholarship (study at Cambridge) Gilman Scholarship (study abroad programs) Keasbey Scholarship (study at Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh, or Wales) Luce Scholarship (internships in East Asia, any field except Asian specialties) Schwarzman Scholars Program (at Tsinghua University in Beijing) St. Andrew’s Society Graduate Scholarship -

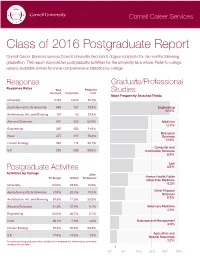

Class of 2016 Postgraduate Report

Cornell Career Services Cornell Career Services Overview of Services Annual Activities Cornell Career Services Class of 2016 Postgraduate Report Individual advising appointments Offers a broad range of programs and services to assist 16,094 and drop-in advising sessions students with their career development. Cornell Career Services surveys Cornell University bachelor’s degree recipients for six months following graduation. This report summarizes postgraduate activities for the university as a whole. Refer to college Career planning Career development and information 503 reports (available online) for more comprehensive statistics by college. Career counseling and testing, library and Internet programs, classroom presentations resources, shadowing and networking opportunities. Students attending programs Job-search strategies 15,443 Response Graduate/Professional Advice on the job search, workshops, employer and presentations Response Rates Total Response career fairs (on and off campus). Surveyed Responses Rate Studies Schools represented at annual Graduate Most Frequently Selected Fields 204 University 3,749 2,649 70.7% Employment services and Professional School Days Interviews (on and off campus), resume Agriculture and Life Sciences 949 757 79.8% Engineering referrals, job postings via the Internet. 22.2% Students attending Graduate and 436 Architecture, Art, and Planning 107 40 37.4% Graduate and professional school advising Professional School Days Advice and workshops on the application process Arts and Sciences 991 623 62.9% Medicine -

2020-21 Churchill Scholars

2020-21 Churchill Scholars Vinay Ayyappan Johns Hopkins University Radiology Anna Biggs Harvard University Applied Mathematics Azim Dharani Duke University Chemistry Thomas Freitag University of Pittsburgh Public Policy Elise Koskelo Pomona College Physics Catherine Lee Yale University Pure Mathematics Jamie Lee US Naval Academy Machine Learning Harrison (Wei Tse) Li UC San Diego Cancer Research UK Alice Lin Princeton University Pure Mathematics Daniel Malawsky UNC Chapel Hill Sanger Institute Srinivas Mandyam University of Pennsylvania Physics Salvatore Pace Boston University Applied Mathematics Mehtaab Sawhney Massachusetts Institute of Technology Pure Mathematics Jasmine Stone Yale University Engineering Tanay Wakhare University of Maryland/College Park Advanced Computer Science Michael Xiao University of Utah MRC Cancer Unit The Winston Churchill Foundation of the United States is pleased to announce the cohort of 16 Churchill Scholars, including one Kanders Churchill Scholarship in Science Policy, for the 2020-21 academic year. The Churchill Scholarship and Kanders Churchill Scholarship are for one year of Master’s study at Churchill College in the University of Cambridge. The awards cover full tuition, a stipend, travel costs, and the chance to apply for a $2,000 special research grant. The Churchill Scholarship dates to 1963. Churchill College was established in 1960 as a predominantly science and technology college and the National and Commonwealth memorial to Sir Winston Churchill. The Churchill Scholarship fulfils Sir Winston’s wish that there always be American students of the highest caliber at the College that bears his name. The Kanders Churchill Scholarship is awarded from a pool of applicants to the Cambridge Master’s in Public Policy. -

Churchill Scholarship Newsletter 2019

201 9 CHURCHILL NEWS THE WINTER ISSUE Newsletter of the Winston Churchill Foundation of the United States CHURCHILL SCHOLARS CHURCHILL’S NEW AMBASSADORS 2019 –20 Esteban Abeyta hen the American Ambassador to the United Kingdom sits at his desk in the Michael Aling Daniel Assumpcao impressive new embassy building near Vauxhall station, a portrait of Sir Winston Meenakshi Chakraborty W Churchill looks down upon him. Churchill would be smiling if he knew that this Ryan Chen year’s sixteen students under the Scholarship that bears his name were invited into the Anthony Coniglio Ambassador’s office recently to discuss their work. Edridge D’Souza Alexander Hwang The Ambassador, Robert Wood “Woody ” Johnson IV, met with the Churchill Cindy Liu Scholars, along with Trustees and friends of the Foundation this November. As the group Clara Ma walked through the lobby, they passed a marble wall of honor listing past American Ambas- Cameron Owen Jesse Palmer sadors, including former Foundation President, Ambassador Lewis Douglas. While the Anita Qualls Scholarship is funded through private donations, it came about as a reflection of the very Brian Seymour close ties between the US and UK and continues to promote scientific cooperation between Jamie Tucker-Foltz the countries. Eric Wang Ambassador Johnson asked each student to tell him where they are from and what they study. It was a happy coincidence that just two weeks earlier, the students had all gone through public engagement training (paid for through our annual fund), where they were ESTD 1963 CHURCHILL taught how to answer this question in 30 seconds! The result was a fascinating discussion on SCHOLARSHIP A life-changing year a wide range of scientific topics, which you can read about in the pages of this newsletter. -

ASU Enterprise

Arizona State University Strategic Enterprise Plan: 2021 Update & Operational and Financial Review Michael M. Crow February 12, 2021 The ASU Enterprise 2 ASU is leading the Fifth Wave First Wave Second Wave Third Wave Fourth Wave Fifth Wave Greek Academies State Colleges Land-Grant Colleges Research Universities National Service Universities 163 6 Harvard College* 1693 College of William and Mary 1876 Johns Hopkins University* 1701 Yale College State-chartered colleges and universities, 1885 Stanford University* 1746 College of New Jersey (Princeton) including teacher colleges and 1890 University of Chicago* 1754 King’s College (Columbia) technological institutes, some private 1755 College of Philadelphia (Penn) 1764 College of Rhode Island (Brown) 1785 University of Georgia* First Wave colleges that evolved into 1766 Queen’s College (Rutgers) 1789 University of North Carolina* research universities 1769 Dartmouth College 1792 University of Vermont Harvard University 1801 University of South Carolina Yale University 1816 University of Michigan Princeton University 1819 University of Virginia* Land-grant colleges and universities Columbia University Schools founded during the early Republic established as a consequence of that established the prototype for the University of Pennsylvania the Morrill Act of 1862 American residential liberal arts college Brown University, etc. 1848 University of Wisconsin 1783 Dickinson College 1851 University of Minnesota 1865 Cornell University* 1793 Williams College 1855 Michigan State University 1867 University of Illinois* Second Wave colleges and universities 1794 Bowdoin College 1855 Penn State University 1868 University of California* that evolved into research universities 1800 Middlebury College 1856 University of Maryland 1869 Purdue University University of Georgia 1832 Wabash College 1858 Iowa State University 1870 Ohio State University University of North Carolina 1833 Oberlin College 1861 Massachusetts Institute 1871 Texas A&M University, etc. -

National Fellowships Flowchart College Center for Research and Fellowships -- 5Th Floor Harper Memorial Library

National Fellowships Flowchart College Center for Research and Fellowships -- 5th Floor Harper Memorial Library For students in their: With an interest in: Should Consider: 1st Year International, Language US-UK Fulbright Summer Institutes, Boren, CLS, DAAD, Gilman, Freeman Welcome to the University of Chicago’s College Center for Research and Fellowships! It’s Research Look to connect yourself to research opportunities on campus and beyond never too early to start considering nationally competitive fellowships as a part of your undergraduate education! Leadership Talk with your advisor about getting involved on campus; Davis Projects for Peace 2nd Year STEM Goldwater, Astronaut Scholarship, DAAD RISE A crucial year for Fellowships. Rubber is meeting the road in academics, research, Public Service Udall Scholarship, Davis Projects for Peace engagement, and leadership. Your 2nd year is the time to consider your path forward. International, Language US-UK Fulbright Summer Institutes, Boren, CLS, DAAD, Gilman, Freeman, HIA 3rd Year Graduate School Beinecke, Rhodes, Marshall, Mitchell, Ertegun, Gates, Schwarzman, Knight-Hennessy The time has come to start thinking of postgraduate STEM Goldwater, Churchill, Astronaut opportunities! Truman and Beinecke in the Fall, followed by Truman Scholarship, Davis Projects for Peace, Udall Scholarship the UK Awards and Fulbright in Public Service the Spring. International, Language Pickering, Boren, CLS, DAAD, Gilman, Freeman, HIA 4th, 5th Year, or Alumni UK and Ireland Awards Rhodes, Marshall, Mitchell, -

Nationally Competitive Awards Annual Report 2014-15.Pages

Evidence Document for Higher Learning Commission Reaccreditation Document Title: Office of Nationally Competitive Awards Annual Report Office of Origin: Enrollment Services Document Summary: The Office of Nationally Competitive Awards helps students apply for merit-based scholarships, fellowships, internships, and study abroad programs. Na#onally Compe##ve Awards The Office of Nationally Competitive Awards (ONCA) provides information, resources, and support for students applying for a variety of merit-based, nationally competitive undergraduate and post-graduate opportunities, including scholarships, fellowships, internships, and study abroad programs. ONCA manages outreach and advising for students at the freshman through graduate level and works to connect students with opportunities appropriate to their long-term academic and professional goals. In addition to offering individual advising appointments, ONCA staff members organize informational meetings, group workshops, and practice interviews as means of preparing students to compete at the state and national level. The office also supports students applying to graduate, law, and medical school (the director sits on the Pre-Medical Advisory Committee). By The Numbers During the 2014-15 academic year, ONCA completed a review of the University of Arkansas’s standing in several key scholarship programs. In two major undergraduate competitions, the Goldwater Scholarship and the Truman Scholarship, the U of A is ranked 1st in the SEC. In the Goldwater, the University’s all-time total of 50 scholars places the U of A 16th among public institutions and 30th among both public and private institutions. For the Truman Scholarship, the University’s total of 19 scholars places the U of A 14th among public institutions and 31st among both public and private institutions. -

Jonathan Wang Citizenship: United States

B [email protected] Í https://www.jonathanpwang.com Jonathan Wang Citizenship: United States Professional Positions 9/2021– Senior Postdoctoral Fellow, Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, Waterloo, Ontario, Present Canada. 9/2018– NSF Postdoctoral Fellow/Pure Math Instructor, MIT, Cambridge, MA. 5/2021 Sponsoring Scientist: Roman Bezrukavnikov 9/2017– Member, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, NJ. 7/2018 Research Interests Representation Theory, Automorphic Forms, L-functions, Relative & Geometric Langlands Programs Education 2012–2017 Ph.D. in Mathematics, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL. Thesis Title: On an invariant bilinear form on the space of automorphic forms via asymptotics Advisor: Vladimir Drinfeld 2011–2012 MASt, Mathematics, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. Essay Title: Introduction to D-modules and representation theory Advisor: Ian Grojnowski 2007–2011 A.M., Mathematics, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. 2007–2011 A.B., Mathematics, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, summa cum laude. Thesis Title: The moduli stack of G-bundles Advisor: Dennis Gaitsgory Fellowships and Awards 2018–2021 NSF Postdoctoral Research Fellowship (MSPRF) DMS-1803173 2017 Wirszup Fellowship, University of Chicago Mathematics Department 2013–2016 National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship (NDSEG) 2011–2013 NSF Graduate Research Fellowship 2011–2012 Churchill Scholarship 2011 Herb Alexander Award, Harvard Mathematics Department Teaching Spring 2021 Instructor, MIT, Virtual. 18.704 Seminar in Algebra, undergraduate seminar with 12 students on Representation Theory of Lie Algebras via Examples. Fall 2020 Recitation Instructor, MIT, Virtual. 18.06 Linear Algebra, 2 recitations with 19, 18 students, 145 students in class. Fall 2019 Recitation Instructor, MIT, Cambridge, MA. 18.02 Multivariable Calculus, 3 recitations with 17, 10, 20 students, 359 students in class. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS American Association for the Advancement of Science AAAS Science & Technology Policy Fellowship 1 Cultural Vistas Alfa Fellowship Program 5 Astronaut Scholarship Foundation Astronaut Scholarship 8 The Sperry Fund Beinecke Scholarship 11 National Security Education Program Boren Awards for International Study 13 The Winston Churchill Foundation of the United States Churchill Scholarship 16 U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Educational & Cultural Affairs Critical Language Scholarship 18 German Academic Exchange Service DAAD 22 The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering & Medicine Ford Foundation Fellowship Program 24 US-UK Fulbright Commission Fulbright UK Summer Institute 28 U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Educational & Cultural Affairs Fulbright U.S. Student Program 30 Carnegie Endowment for International Peace James C. Gaither Junior Fellows Program 34 Gates Cambridge Gates Cambridge Scholarship 36 The Alexander von Humboldt Foundation German Chancellor Fellowship 39 U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship 41 Barry Goldwater Scholarship and Excellence in Education Foundation Goldwater Scholarship 44 Fannie & John Hertz Foundation Hertz Foundation Fellowship 46 Humanity in Action Humanity in Action Fellowship 49 Institute of Current World Affairs Institute of Current World Affairs Fellowship 51 Winston Churchill Foundation Kanders Churchill Scholarship 54 The Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program Knight-Hennessy Scholarship 56 Victims of Pan Am Flight 103, Inc. Legacy Award 59 The Henry Luce Foundation The Luce Scholarship Program 61 James Madison Memorial Fellowship Foundation James Madison Fellowships 64 Marshall Aid Commemoration Commission Marshall Scholarship 67 U.S.-Ireland Alliance George J. Mitchell Scholarship Program 69 Udall Foundation Native American Congressional Internship 71 The Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation The Charlotte W. -

University of Pittsburgh History of Award Winners

UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH HISTORY OF AWARD WINNERS AWARDS & RECIPIENTS YEAR AMERICAN ASSOCATION OF TEACHERS OF JAPANESE BRIDGING SCHOLARSHIP Kaitlin Wise 2014 Meghan Hirsh 2014 AMGEN SCHOLARS SUMMER RESEARCH PROGRAM IN SCIENCE AND BIOTECHNOLOGY Carly O'Connor 2015 Katarina Clemens 2014 Swati Rajprohat 2014 Kevin Day 2013 Brittany Charsar 2012 Daniel Holohan 2012 Lisa Volpatti 2012 Naomi Latorraca 2012 Paras Minhas 2012 Michael Gowen 2010 Chris Zimmerman 2009 ASIA PACIFIC FOUNDATION SCHOLARSHIP Brendan Morrell 2009 Cory Rodgers 2009 Julie Percha 2009 BEINECKE SCHOLARSHIP Simon Brown 2014 BOREN SCHOLARSHIP FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDY Marjorie Tolsdorf 2015 Joseph Andros 2015 Brianna Gasgonia 2015 Joseph Sell 2015 Zachary Patton 2014 Patrick Farrell 2013 Abigail Majane 2013 Megan Carson 2013 Viveka Mandava 2013 Arielle Ross 2012 BOREN SCHOLARSHIP FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDY UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH HISTORY OF AWARD WINNERS Noah Haibach 2012 Cody Dickerson 2011 Devani Whitehead 2011 Lorraine Keeler 2011 Russell Ottalini 2011 Stacey Stachera 2011 Gregory Withers 2010 Heather Duschl 2010 Michelle Sattazahn 2010 Utsav Bansal 2010 Natalie Arutynov 2009 Ben Mericli 2008 Carl Seeno 2007 Brenton Hull 2006 Ravi Sharma 2006 Mary Goehrig 2005 Robert Ness 2004 David Gourley 2003 Jennifer Murawski 2003 Julie Dumbovich 2001 Sally Schlippert 2001 Sarah Oh 2001 James Swetz 1999 Michael Speerschneider 1999 Melissa Vander Kooi 1998 Shelly Culbertson 1998 Daniel Weiss 1997 Dorcas Jenkins 1997 Kenneth Knight 1997 CARNEGIE ENDOWMENT FOR INTERNATIONAL PEACE JUNIOR FELLOWSHIP -

List of UK Opportunities for Graduate And

Study Abroad in England, Ireland, or Scotland Compiled the Office of Distinguished Scholarships at UNC Fourth-year students, Recent graduates, Alumni (*UNC endorsement is required) The Churchill Scholarship* Award: Provides funding to American students for a year of Master’s study in science, mathematics, and engineering at the University of Cambridge, based at Churchill College. The Scholarship is tenable from nine to twelve months, in accordance with the academic program. It covers all University and College fees, a living allowance, and an allowance for travel to and from the United Kingdom. (The Kanders Churchill Scholarship funds the study of science policy at the Cambridge Master's in Public Policy.) Eligibility: Must be a citizen of the United States, either native born or naturalized; be a senior or a student who has graduated within the past 12 months; and hold a bachelor's degree or an equivalent, and may not have attained a doctorate. Criteria: 1. Outstanding academic achievement, especially in the major (unofficial GPA standards are 3.7+), 2. Proven talent in research and a capacity to contribute to the advancement of knowledge in the sciences, engineering, or mathematics by pursuing original, creative work at an advanced level, 3. Outstanding personal qualities UNC Endorsement Deadline: Early October University of Cambridge Deadline: Mid-October (Must apply separately) Website: http://www.winstonchurchillfoundation.org/ Ertegun Graduate Scholarship Programme in the Humanities Award: Funds full-time graduate degrees in various subjects in the Humanities at Oxford University. The scholarship will cover 100% of University and college fees and a grant for living costs. Eligibility: Must be applying to start a new full-time graduate course in the Humanities at Oxford.