The Dallams in Brittany Michel COCHERIL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Levés Par Lidar Aéroporté Du Littoral Finistérien

Levés par LiDAR aéroporté du littoral finistérien µ ILE-DE-BATZ ROSCOFF BRIGNOGAN- SANTEC PLAGE SIBIRIL SAINT- PLOUESCAT POL- GUIMAEC KERLOUAN PLOUNEOUR- PLOUGASNOU CLEDER DE-LEON LOCQUIREC TREZ CARANTEC TREFLEZ PLOUGOULM SAINT-JEAN- PLOUGUERNEAU CC Baie du Kernic GUISSENY GOULVEN DU-DOIGT TREFLAOUENAN PLOUENAN PLOUEZOC'H PLOUIDER PLOUNEVEZ- HENVIC LANDEDA LOCHRIST CC Pays Léonard LOCQUENOLE SAINT-PABU CC Pays de Lesneven et LAMPAUL- LANNILIS de la côte des Légendes MORLAIX PLOUDALMEZEAU LOC- LANDUNVEZ TREGLONOU BREVALAIRE PLOUDALMEZEAU PLOUGUIN PLOUVIEN PORSPODER Morlaix Communauté CC Pays des Abers OUESSANT LANILDUT LAMPAUL- PLOUARZEL CC Pays d'Iroise PLOUARZEL LANDERNEAU Brest métropole ILE-MOLENE océane GUIPAVAS LA FOREST- PLOUMOGUER LANDERNEAU LE RELECQ- BREST DIRINON TREBABU LOCMARIA- KERHUON PLOUZANE LOPERHET CC Pays de LE CONQUET PLOUZANE PLOUGASTEL- Landerneau-Daoulas PLOUGONVELIN DAOULAS DAOULAS ROSCANVEL LOGONNA-DAOULAS HANVEC HOPITAL-CAMFROUT LE FAOU CAMARET-SUR-MER LANVEOC LANDEVENNEC CC Aulne Maritime CC Presqu'île ROSNOEN CROZON de Crozon ARGOL TELGRUC-SUR-MER TREGARVAN SAINT-NIC DINEAULT PLOMODIERN CC Pays de Châteaulin et du Porzay PLOEVEN PLONEVEZ-PORZAY POULLAN- BEUZEC-CAP-SIZUN SUR-MER KERLAZ CLEDEN-CAP-SIZUN DOUARNENEZ ILE-DE-SEIN GOULIEN CC Cap-Sizun CC Pays de PLOGOFF Douarnenez PRIMELINESQUIBIEN AUDIERNE MAHALON PLOUHINEC Quimper Communauté PLOZEVET QUIMPER POULDREUZIC CC Haut Pays Bigouden PLOVAN Concarneau Cornouaille PLOMELIN Agglomération CC Pays TREOGATPLONEOUR- Fouesnantais LANVERN GOUESNACH LA FORET- FOUESNANT -

Concarneau US 2 – Chateaulin FC Lorient CEP – Plobannalec Lesc

Concarneau US 2 – Chateaulin FC La Montagne US – Douarnenez SM Plabennec ST 2 – Plobannalec Lesc. Lorient CEP – Plobannalec Lesc. St Renan EA – Auray FC Concarneau US 2 – Lorient CEP Plabennec ST 2 – Guipavas Gas Reun Guipavas Gas Reun – Ergue Gab.P.D. Ergue Gab.P.D. – Chateaulin FC Ergue Gab.P.D. – St Renan EA Chateaulin FC – Plabennec ST 2 Landerneau FC – La Montagne US Auray FC – La Montagne US Plobannalec Lesc. – Concarneau US 2 Douarnenez SM – St Renan EA Landerneau FC – Douarnenez SM Lorient CEP – Landerneau FC Auray FC – Guipavas Gas Reun St Renan EA – La Montagne US Plabennec ST 2 – Concarneau US 2 Guipavas Gas Reun – St Renan EA Guipavas Gas Reun – Douarnenez SM Ergue Gab.P.D. – Lorient CEP Chateaulin FC – La Montagne US Chateaulin FC – Auray FC La Montagne US – Guipavas Gas Reun Plobannalec Lesc. – Douarnenez SM Plobannelec Lesc. – Ergue Gab.P.D. Douarnenez SM – Chateaulin FC Lorient CEP – Auray FC Lorient CEP – Plabennec ST 2 Auray FC – Plobannalec Lesc. Concarneau US 2 – Ergue Gab.P.D. Concarneau US 2 – Landerneau FC Landerneau FC – St Renan EA Plabennec ST 2 – Landerneau FC . Auray FC – Concarneau US 2 Chateaulin FC – Guipavas Gas Reun Douarnenez SM – Plabennec ST 2 Ergue Gab.P.D. – Plabennec ST 2 Plobannalec Lesc. – St Renan EA Auray FC – Ergue Gab.P.D. Douarnenez SM – Lorient CEP Lorient CEP – La Montagne US La Montagne US – Concarneau US 2 La Montagne US – Plobannalec Lesc. Concarneau US 2 – Douarnenez SM Landerneau FC – Chateaulin FC St Renan EA – Chateaulin FC Plabennec ST 2 – Auray FC Guipavas Gas Reun – Plobannalec Lesc. -

Une Ambition Pour La Jeunesse

AGGLO MAGAZINE MAG D’INFORMATION DE QUIMPER BRETAGNE OCCIDENTALE N°79 NOV./DÉC.2018 LE www.quimper-bretagne-occidentale.bzh ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEUR p 7 UNE AMBITION POUR LA JEUNESSE HISTOIRE/p.15 AGENDA/p.16 LES GENS D’ICI/p.20 Le 11 novembre 1918 Les Échappées Aurélie Stéphan de Noël BRIEC / ÉDERN / ERGUÉ-GABÉRIC / GUENGAT / LANDRÉVARZEC / LANDUDAL / LANGOLEN LOCRONAN / PLOGONNEC / PLOMELIN / PLONÉIS / PLUGUFFAN / QUÉMÉNÉVEN / QUIMPER Vivre ou investir QUIMPER NOUVEAU Les Hauts de Feunteun VOTRE APPARTEMENT PERSONNALISABLE UN EMPLACEMENT EXCEPTIONNEL AU CENTRE-VILLE DE QUIMPER Appartements neufs du T2 au T4 CONTACT www.polimmo.fr 02 98 55 81 91 02 98 95 99 92 / 06 78 88 68 02 www.acadie-quimper.com Espacil_102x150.pdf 1 02/10/2018 17:21:35 devient C M J CM MJ CJ CMJ N Aide à Garde Entretien l’autonomie d’enfants ménager 122, avenue de la France Libre - 29000 Quimper Tél. 09 81 71 27 71 - [email protected] www.adomis-quimper.com 3 Vivre ou investir PENNAD-STUR/ÉDITO NOUVEAU QUIMPER LE JOURNAL D’INFORMATION DE QUIMPER BRETAGNE OCCIDENTALE DÉC. 2018 NOV. Communauté d’agglomération / regroupant les communes de Briec, Édern, Les Hauts de Feunteun Ergué-Gabéric, Guengat, Landrévarzec, Landudal, Langolen, Locronan, Plogonnec, AGGLO Plomelin, Plonéis, Pluguffan, VOTRE APPARTEMENT Quéménéven, Quimper Ce numéro comprend : • Le mag + Agglo, 20 p., CONFIANCE LUDOVIC PERSONNALISABLE tiré à 58 450 exemplaires. JOLIVET LE MAG LE MAG • Pour les habitants de Quimper MAIRE uniquement : Le mag + Quimper, Il est bon d’avoir des motifs de confiance en cahier de 16 pages broché au centre du mag DE QUIMPER, et tiré à 40 783 exemplaires. -

Christian Symbolism Little Books on Art Enamels

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com Christiansymbolism Mrs.HenryJenner THG UN1YGRSITY Of CALIFORNIA LIBRARY LITTLE BOOKS ON ART GENERAL EDITOR: CYRIL DAVENPORT CHRISTIAN SYMBOLISM LITTLE BOOKS ON ART ENAMELS. By Mrs. Nelson Dawson. With 33 illustrations. MINIATURES. Ancient and Modern. By Cyril Davenport. With 46 illus trations. JEWELLERY. By Cyril Davenport. With 4i illustrations, BOOKPLATES. By Edward Almack, F. S. A. With 42 illustrations. THE ARTS OF JAPAN. By Edward Dillon. With 40 illustrations. ILLUMINATED MSS. By John W. Bradley. With 40 illustrations. CHRISTIAN SYMBOLISM. By Mrs. Henry Jenner. With 40 illustrations. OUR LADY IN ART. By Mrs. Henry Jenner. With 40 illustrations. Frontispieces in color. Each with a Bibliography and Index. Small square 16mo, $1.00 net. A. C. McCluro & Co.. Publishers ' -iTRA lIU'.s t. I' .> m. • -V J CHICAGO A. C. MoCJ,URU & CO. 1910 LITTLE BOOKS ON ART CHRISTIAN SYMBOLISM BY MRS. HENRY JENNER < i WITH 41 ILLUSTRATIONS CHICAGO A. C. McCLURG & CO. 1910 First Published in 1910 Reprinted August 1, 1910 CONTENTS PAGE Introduction xiii CHAPTER I Sacraments and Sacramentals i CHAPTER II The Trinity 21 CHAPTER III The Cross and Passion 46 CHAPTER IV The World of Spirits 64 CHAPTER V The Saints 89 CHAPTER VI The Church 115 CHAPTER VII Ecclesiastical Costume 132 396146 vi CHRISTIAN SYMBOLISM CHAPTER VIII PAGE Lesser Symbolisms 145 CHAPTER IX Old Testament Types 168 Bibliography 177 Index . 181 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS THE LAST JUDGMENT . -

Sur Les Chemins De L'été

Vendredi 28 mai 2021 Sur les chemins de l’été / Sentiers de randonnée Les sentiers de randonnée s’animent tout l’été, en journées et en soirées, les mardis, jeudis ou vendredis pour vous permettre de mieux connaitre la richesse des paysages et du petit patrimoine bâti du territoire de l’agglomération. L’animation « Sur les chemins de l’été » est proposée par Quimper Bretagne Occidentale et les communes de l’agglomération avec le concours des associations suivantes : Amicale laïque des randonneurs d’Ergué-Gabéric, Amicale laïque de Plomelin (randonnée), Association sportive Locronan, Brezhoneg E Ploveilh, Club de gymnastique Landudal, Edern histoire et patrimoine, Galouperien Briec, Guengat Rando, Keme en fêtes, Plonéis Loisirs, Rando pluguffanaise, Sénior Sport Santé à Quimper, Société d’horticulture de Quimper. Le programme des mois de Juin, Juillet et Août JUIN* : 7 randonnées / 2 balades thématiques * La soirée du 1er juin (Plonéis) est annulée, de même que la balade thématique planifiée le 10 juin (Plomelin, Lycée Kerbernez). Jeudi 10 / QUÉMÉNÉVEN. Départ 19h, gare de Quéménéven (8 km - 2h - difficulté 2) Vendredi 11 / PLUGUFFAN. Départ 18h, complexe S. Allende (8,5 km - 2h15 - difficulté 2) Mardi 15 / QUIMPER. Départ 13h45. Stade N. Kervahut (8,7 km - 2 h 15, difficulté 2 - (variante courte de 5,6 km)). Circuit à parcourir également en autonomie de 14h30 à 16h Mardi 15 / PLOMELIN. Départ 19h, Espace Kerne (9 km - 2h30 - difficulté 2) Vendredi 18 / ERGUÉ-GABÉRIC. Départ 18h30, chapelle de Ker-Anna (8,5 km - 2h30 - difficulté 2). Circuit à parcourir également en autonomie de 14h à 17h Vendredi 18 / QUIMPER. -

Fichier Entreprises Au 07 05 2021 Partenaires

Offres CFA Bâtiment de QUIMPER Tél : 02 98 95 97 26 [email protected] 07 Mai 2021 PLOUGONVELIN BAC PRO TISEC SAINT POL DE LEON BREST BP CARRELEUR MOSAISTE LE CLOITRE PLEYBEN QUIMPERLE FOUESNANT MOELAN SUR MER GOURLIZON BP COUVREUR PLOMELIN CHATEAULIN PLOUNEOUR TREZ CONCARNEAU NEVEZ BP ELEC CLOHARS CARNOET LE FAOU GUISSENY TELGRUC SUR MER ELLIANT PLOUGUERNEAU BP MACON PLUGUFFAN PONT CROIX BREST LANDERNEAU PLOUGONVEN PLESCOP BRIEC BANNALEC CLOHARS CARNOET PLONEVEZ DU FAOU BP MENUISIER GUISSENY CLEDER LOCMARIA BERRIEN QUIMPER GUILERS SAINT YVI PLABENNEC AUDIERNE CONCARNEAU BP PAR LE FAOUET GUIPAVAS HUELGOAT LANDERNEAU CHATEAUNEUF DU FAOU BREST QUIMPER PLABENNEC SAINT THEGONNEC PLEUVEN LE CLOITRE PLEYBEN CAP CARRELEUR MOSAISTE PLABENNEC QUIMPER EDERN PLABENNEC PENMARCH PONT L ABBE SAINT MARTIN DES CHAMPS LOPERHET GUENGAT PLOUARZEL ST POL DE LEON LANDIVISIAU GUILER SUR GOYEN QUIMPERLE CLEDER KERNILIS CAP CHARPENTIER BOIS SAINT DERRIEN PLOUIGNEAU PLONEOUR LANVERN LANDERNEAU CLEDER PLOUARZEL QUIMPER PLOEMEUR COBARM PONT CROIX CLEDER PLOUARZEL BENODET PLOUHINEC GUIPAVAS CONCARNEAU BREST CAP COUVREUR CROZON CLOHARS CARNOET CLEDEN POHER PLOUVIEN SAINT THURIEN PLOGONNEC GUICLAN PLUGUFFAN LANDIVISIAU TREGOUREZ GUENGAT TREGLONOU MILIZAC BREST PLOMELIN PLOMELIN FOUESNANT GOUESNOU PLOMELIN PLOUGUIN PLONEOUR LANVERN CHATEAULIN PLONEVEZ PORZAY BENODET ERGUE GABERIC PLOUZEVEDE KERLAZ CAP COUVREUR PLOUNEVEZ LOCHRIST ROSPORDEN CONCARNEAU GUICLAN PLOUEDERN PLOUGUIN PLOUNEOUR TREZ SCAER QUIMPERLE PLOUGOULM SCAER PLABENNEC PLONEOUR LANVERN ELLIANT -

Gouesnou Pour Vous (Article De La Majorité)

GOUESNOU Le www.Gouesnou.fr #28 unan e sk arantez novembre oulm ar g 2016 Rentrée des classes 2016 8/9 Gouesnou rentrée 2016 Retour en images 3 Social Gouesnou les dispositifs jeunesse 7 Finances- Personnel Focus sur les services municipaux 12-13 GOUESNOU LE MAG #28 - NOVEMBRE 2016 Le magazine d’information de la Ville de Gouesnou Magazin kelaouiñ Gouenoù ÉDITO 2 Pennad-stur P3 Retour en images Gouesnou, rentrée 2016 P4-5 Culture Jeux vidéo, papotages et babillages... Stéphane ROUDAUT, Maire de Gouesnou P6 Sport @SteRoudaut Romain Merieult P7 Social Les dispositifs Jeunesse LA MÉTHODE COMPTE P8-9 Enfance TOUT AUTANT QUE LE PROJET ! Rentrée scolaire 2016/2017 P10 Actualités a méthode compte tout autant que le projet lui-même ! Trop souvent, les responsables Lpublics et les élus ont tendance à travailler seuls, à s’isoler, dans la définition puis la réalisation d’un projet. Ce n’est pas notre conception des choses ! P12-13 Finances/Personnel Focus sur les services municipaux Ici à Gouesnou, nous avons pris le parti de porter une cohérence d’ensemble, ensuite de fixer des priorités, puis d’établir une programmation cohérente des investissements et de le faire avec les usagers, les acteurs de la vie locale eux-mêmes. P14 Culture Après le Parc municipal du Crann, nous lançons aujourd’hui un projet majeur : celui de Faire bien avec peu ! la refonte de la salle de Kerloïs. Depuis le début de l’année, l’ouvrage a maintes fois été remis sur le métier, en collaboration très étroite avec les clubs et les associations concernés. -

Carte De Sectorisation Des Collèges

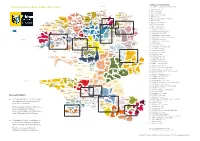

Collèges de rattachement Sectorisation des collèges publics 2021- 2022 ILE-DE-BATZ Zones hachurées : rattachement à plusieurs collèges 1 - BANNALEC - Jean Jaurès ROSCOFF SANTEC 2 - BREST - Anna Marly PLOUESCAT !(58 !(40 3 - BREST - L'Harteloire PLOUNEOUR- SAINT-POL-DE-LEON KERLOUAN 4 - BREST - Les Iles-du-Ponant BRIGNOGAN-PLAGES 39 CLEDER SIBIRIL PLOUGOULM PLOUGASNOU !( !(12 LOCQUIREC TREFLEZ SAINT-JEAN-DU-DOIGT GUIMAEC 5 - BREST - L'Iroise CARANTEC GUISSENY GOULVEN PLOUGUERNEAU 6 - BREST - La Fontaine Margot - Kéranroux PLOUNEVEZ-LOCHRIST TREFLAOUENAN PLOUENAN HENVIC PLOUEZOCH LANMEUR!(28 MESPAUL LANDEDA SAINT-FREGANT PLOUIDER 7 - BREST - Kerhallet KERNOUES TREZILIDE LOCQUENOLE LANNILIS !(29 PLOUEGAT-GUERAND 8 - BREST - Les Quatre Moulins !(38 SAINT-PABU KERNILIS LESNEVEN SAINT-VOUGAY PLOUZEVEDE TAULE LAMPAUL-PLOUDALMEZEAU !(32 MORLAIX LANARVILY GARLAN 9 - BREST - Penn ar C'hleuz LE FOLGOET LANHOUARNEAU LANDUNVEZ PLOUDALMEZEAU TREGLONOU PLOUVORN LOC-BREVALAIRE !(35 10 - BREST - Saint-Pol-Roux PLOUVIEN SAINT-MEEN SAINT-MARTIN-DES-CHAMPS!(57 PLOUGUIN PLOUGAR !( TREGARANTEC 34 PLOUIGNEAU LE DRENNEC SAINT-DERRIEN PLOUGOURVEST 11 - BRIEC - Pierre Stéphan SAINTE-SEVE PORSPODER PLOURIN PLOUEGAT-MOYSAN COAT-MEAL PLOUDANIEL GUICLAN 12 - CARANTEC - Les Deux Baies TREOUERGAT PLOUNEVENTER OUESSANT LANILDUT BOURG-BLANC PLEYBER-PLOURIN-LES- !(36 TREMAOUEZAN SAINT-SERVAIS BODILIS CHRIST 13 - CARHAIX-PLOUGUER - Beg Avel BRELES !(27LANDIVISIAU MORLAIX LANRIVOARE PLABENNEC KERSAINT- LANNEUFFRET SAINT-THEGONNEC- GUERLESQUIN 14 - CHATEAULIN - Jean-Moulin -

Language Diversity and Linguistic Identity in Brittany: a Critical Analysis of the Changing Practice of Breton

Language diversity and linguistic identity in Brittany: a critical analysis of the changing practice of Breton Adam Le Nevez PhD 2006 CERTIFICATE OF AUTHORSHIP/ORIGINALITY I certify that the work in this thesis has not been previously submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that this thesis has been written by me. Any help I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Signature ________________________________________ Adam Le Nevez i Acknowledgements There are many people whose help in preparing this thesis I would like to acknowledge and many others whom I would like to thank for their support. Many thanks go to Alastair Pennycook, Francis Favereau and Murray Pratt for their encouragement, support, advice and guidance; to Julie Chotard, Amandine Potier- Delaunay, Justine Gayet and Catherine Smith for their proofreading and help in formatting. Thanks too to my family and the many friends and colleagues along the way who encouraged me to keep going. Special thanks go to Astrid and Daniel Hubert who lent their farmhouse to a stranger out of the kindness of their hearts. Finally, thanks go to the generosity of all those who participated in the research both formally and informally. Without their contributions this would not have been possible. ii Table of Contents ABSTRACT................................................................................................................................................ V INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1: THEORETICAL APPROACHES TO LINGUISTIC DIVERSITY .......................... -

Arrêté Préfectoral)

Secteur d'information sur les Sols (SIS) Identification Identifiant 29SIS02847 Nom usuel Ancienne décharge de Kervennou Adresse Kervennou Lieu-dit Département FINISTERE - 29 Commune principale BODILIS - 29010 Caractéristiques du SIS Le site correspond à une ancienne carrière remblayée par des déchets, dont les ordures ménagères, les bois, les monstres, les déchets verts et les gravats. Les dépôts ont une hauteur de 5 à 10 m. Les dépôts ont débuté avant 1963 et ont cessé au début des années 2000. Une partie du site a été reconfigurée et accueille une déchetterie de la Communauté de Communes du Pays de Landivisiau. L'autre partie a continué un temps à accueillir des ordures ménagères avant d'être réhabilitée en étant recouverte de terre et végétalisée. Etat technique Site à connaissance sommaire, diagnostic éventuellement nécessaire Observations Références aux inventaires Organisme Base Identifiant Lien Etablissement public - ADEME Base ou inventaire non précisé 000 Administration - Autre Base ou inventaire non précisé Infos UT29 Sélection du SIS Statut Consultable Critère de sélection Terrains concernés à risques potentiels, à diagnostiquer Commentaires sur la sélection Ancienne décharge. Caractéristiques géométriques générales Coordonnées du centroïde 175700.0 , 6847184.0 (Lambert 93) Superficie totale 45964 m² Perimètre total 2457 m / 13 / Liste parcellaire cadastral Date de vérification du parcellaire Commune Section Parcelle Date génération BODILIS ZB 205 06/06/2017 BODILIS ZB 206 06/06/2017 BODILIS ZB 211 06/06/2017 BODILIS ZB 215 -

Guide Touristique PAYS DE LANDERNEAU-DAOULAS2017 Vers Lesneven Trémaouézan Landivisiau Vers Rennes - Morlaix P

guide touristique PAYS DE LANDERNEAU-DAOULAS2017 Vers Lesneven Trémaouézan Landivisiau Vers Rennes - Morlaix P. 6 P.16 Lanneufret Plouédern St-Thonan la Roche-Maurice CULTURE ESCALES Vers Brest ET PATRIMOINE LITTORALES St-Divy Ploudiry Landerneau la Martyre la Forest- Pencran Landerneau Tréflévénez Sizun l ’ É l o r n St-Urbain P. P. Brest Dirinon 22 28 le Tréhou ESCAPADES LOISIRS Vers Brest Loperhet EN CAMPAGNE POUR TOUS Irvillac St-Eloy Daoulas Logonna- Hanvec Daoulas L’Hôpital- Camfrout Vers Quimper Forêt P. 32 du Cranou BREST TERRES OCÉANES PAYS DE LANDERNEAU DAOULAS 3 Vers Lesneven Trémaouézan Landivisiau Vers Rennes - Morlaix Lanneufret Plouédern St-Thonan la Roche-Maurice Vers Brest St-Divy Ploudiry Landerneau la Martyre la Forest- Pencran Landerneau Tréflévénez Sizun l ’ É l o r n St-Urbain Dirinon Brest le Tréhou Vers Brest Loperhet Irvillac St-Eloy Daoulas Logonna- Hanvec Daoulas L’Hôpital- Camfrout Vers Quimper Forêt du Cranou NUMÉROS D'URGENCE Pompiers : 18 Samu : 15 Police : 7 ou 0 298 856 890 Gendarmerie : 0 298 850 082 Hôpital Landerneau : 0 298 218 000 CHU Brest : 0 298 223 333 Centre antipoison : 0 299 592 222 Urgences : 112 4 guide touristique 2017 un peu de breton NOS LES BRETONS Difficile de s’y retrouver parmi les noms de famille COMMUNES locaux, mais quand vous verrez la personne, vous PLOU : vous indique que ce village était à l’ori- comprendrez vite pourquoi son ancêtre a été nom- gine une paroisse. À Plouédern se trouve l’église mé ainsi ! St Edern. Tal = le front - Blev = cheveux - Lagad = œil - Skouarn = oreille - Dant = dent PENN : signifie tête, bout, cap, extrémité. -

Le Pays De Lesneven-Côte Des Légendes En Chiffres

LE PAYS DE LESNEVEN CÔTE DES LÉGENDES EN CHIFFRES Atlas sociodémographique I avril 2012 Réf. 12/35 2 Le Pays de Lesneven Côte des Légendes en chiffres Atlas sociodémographique I avril 2012 Avant propos L’agence d’urbanisme du Pays de Brest réédite les atlas socio-démographiques des commu- nautés du Pays de Brest. Ces atlas sont fondés en grande partie sur les résultats du recensement de la population de l’INSEE et ont pour objectif de proposer une analyse transversale des territoires composant le Pays de Brest. Ils offrent l’occasion de présenter la situation actuelle et d’analyser les évolutions constatées depuis le recensement de 1999. 3 grandes thématiques sont abordées : Population Habitat Economie. La Communauté de communes du Brignogan-Plage Kerlouan Pays de Lesneven Côte des Légendes Plounéour-Trez dans le Pays de Brest Guissény Goulven St-FrégantC.C. du Pays deKernouës LesnevenPlouider Kernilis Le Folgoët Lesneven Lanarvilyet Côte des LégendesSt-Méen Trégarantec Ploudaniel Le Pays de Lesneven Côte des Légendes en chiffres 3 Atlas sociodémographique I avril 2012 4 Le Pays de Lesneven Côte des Légendes en chiffres Atlas sociodémographique I avril 2012 Sommaire Avant propos ..................................................................3 1. La population .........................................................6 26 311 habitants en 2008 ..............................................6 Une densité supérieure à la moyenne......................6 Une population qui progresse de nouveau ..............7 Une population vieillissante.........................................8 Les origines de la progression de la population ......9 4 400 habitants ne résidaient pas dans la commu- nauté 5 ans auparavant ............................................. 10 Un quart des nouveaux habitants résidaient dans Brest métropole océane ............................................ 10 Des revenus fiscaux inférieurs à la moyenne ........