Preventing Extinctions Post-2020 Requires Recovery Actions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Insect Conservation and Islands Insect Conservation and Islands

INSECT CONSERVATION AND ISLANDS INSECT CONSERVATION AND ISLANDS Editor T. R. New La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia Reprinted from Journal of Insect Conservation Volume 12, Numbers 3–4 (2008) 123 A C.I.P. Catalogue record for this book is available from the library of Congress. ISBN-13 978-1-4020-8781-3 (HB) ISBN-13 978-1-4020-8782-0 (e-book) Published by Springer P.O. Box 17, 3300 AA Dordrecht, The Netherlands www.springer.com Cover illustration: The cover illustration shows several examples of spectacular weta (Orthoptera) from New Zealand, where their conservation has depended largely on offshore islands as refuges and introduction sites, as discussed in papers in this publication. The insects can be fitted with harmonic radar transponders or micro- transmitters for individual tracking. Shown are a Cook Strait Giant Weta, and two Mercury Island Tusked Weta (photograph courtesy of Danny Thornburrow, Corinne Watts and Ian Stringer). Printed on acid-free paper All Rights Reserved Ó 2008 Springer No part of the material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner. Table of Contents EDITORIAL A special issue on insect conservation and islands T.R. New 1 PAPERS Insect conservation on islands: setting the scene and defining the needs T.R. New 3–10 Butterflies of European islands: the implications of the geography and ecology of rarity and endemicity for conservation R.L.H. Dennis · L. -

Synopsis of the Hymenopteran Fauna of Lord Howe Island with a Preliminary Checklist of Species

Zootaxa 3931 (3): 423–432 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2015 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3931.3.6 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:4FA7FEAD-1622-413C-8251-B7470405D7B7 Synopsis of the hymenopteran fauna of Lord Howe Island with a preliminary checklist of species JOHN T. JENNINGS & ANDREW D. AUSTIN Australian Centre for Evolutionary Biology and Biodiversity, and School of Biological Sciences, The University of Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Abstract Lord Howe Island is an eroded remnant of a shield volcano approximately 600 km northeast of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. It has fascinated biologists for more than a century because of its unique and iconic fauna and flora, and was declared a World Heritage Site in 1982. Although the terrestrial invertebrate fauna is reasonably well known for many groups, most Hymenoptera, apart from ants, have received scant attention. Here we use material collected from a recent intensive invertebrate survey, in conjunction with the published literature, to provide an overview of the Hymenoptera known from the island that can act as a basis for future taxonomic and biodiversity research. In doing so, we record 318 species from 31 hymenopteran families from the Island, and assess the proportion that are flightless and likely to be en- demic to the island. Key words: oceanic island, endemic species, apterous, brachypterous Introduction Lord Howe Island, a World Heritage Site of global significance since 1982, is located approximately 600 km northeast of Sydney, New South Wales (Fig. -

Spineless Spineless Rachael Kemp and Jonathan E

Spineless Status and trends of the world’s invertebrates Edited by Ben Collen, Monika Böhm, Rachael Kemp and Jonathan E. M. Baillie Spineless Spineless Status and trends of the world’s invertebrates of the world’s Status and trends Spineless Status and trends of the world’s invertebrates Edited by Ben Collen, Monika Böhm, Rachael Kemp and Jonathan E. M. Baillie Disclaimer The designation of the geographic entities in this report, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expressions of any opinion on the part of ZSL, IUCN or Wildscreen concerning the legal status of any country, territory, area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Citation Collen B, Böhm M, Kemp R & Baillie JEM (2012) Spineless: status and trends of the world’s invertebrates. Zoological Society of London, United Kingdom ISBN 978-0-900881-68-8 Spineless: status and trends of the world’s invertebrates (paperback) 978-0-900881-70-1 Spineless: status and trends of the world’s invertebrates (online version) Editors Ben Collen, Monika Böhm, Rachael Kemp and Jonathan E. M. Baillie Zoological Society of London Founded in 1826, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) is an international scientifi c, conservation and educational charity: our key role is the conservation of animals and their habitats. www.zsl.org International Union for Conservation of Nature International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) helps the world fi nd pragmatic solutions to our most pressing environment and development challenges. www.iucn.org Wildscreen Wildscreen is a UK-based charity, whose mission is to use the power of wildlife imagery to inspire the global community to discover, value and protect the natural world. -

Once Declared Extinct, Lord Howe Island Stick Insects Really Do Live 5 October 2017

Once declared extinct, Lord Howe Island stick insects really do live 5 October 2017 introduction on Lord Howe Island could be done successfully, the researchers say. "We found what everyone hoped to find—that despite some significant morphological differences, these are indeed the same species," says Alexander Mikheyev at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology in Japan. Using DNA sequence data from the Ball's Pyramid population, the researchers assembled a draft genome of the captive bred insects along with their complete mitochondrial genome. The effort revealed a massive genome, which appears to have been duplicated more than once to contain six Dryococelus australis pair on ficus. Credit: Rohan copies of each chromosome. Cleave, Melbourne Zoo, Australia The researchers also re-sequenced mitochondrial genomes from historic museum specimens collected on Lord Howe Island before the extinction Lord Howe Island stick insects were once event. Comparisons between living and dead numerous on the tiny crescent-shaped island off insects found a divergence of less than one the coast of Australia for which they are named. percent—well within the range of differences The insects, which can measure up to 6 inches in expected within a species. The findings suggest length, don't resemble sticks so much as tree that the rediscovered populations are indeed Lord lobsters, as they are also known. After ships Howe Island stick insects. Dryococelus australis accidentally introduced rats to the island about a really has evaded extinction so far. century ago, the Lord Howe Island stick insects quickly disappeared. They were later declared extinct, only to be found again decades later living on Ball's Pyramid, a sheer volcanic stack about 12 miles away. -

Insect Egg Size and Shape Evolve with Ecology but Not Developmental Rate Samuel H

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1302-4 Insect egg size and shape evolve with ecology but not developmental rate Samuel H. Church1,4*, Seth Donoughe1,3,4, Bruno A. S. de Medeiros1 & Cassandra G. Extavour1,2* Over the course of evolution, organism size has diversified markedly. Changes in size are thought to have occurred because of developmental, morphological and/or ecological pressures. To perform phylogenetic tests of the potential effects of these pressures, here we generated a dataset of more than ten thousand descriptions of insect eggs, and combined these with genetic and life-history datasets. We show that, across eight orders of magnitude of variation in egg volume, the relationship between size and shape itself evolves, such that previously predicted global patterns of scaling do not adequately explain the diversity in egg shapes. We show that egg size is not correlated with developmental rate and that, for many insects, egg size is not correlated with adult body size. Instead, we find that the evolution of parasitoidism and aquatic oviposition help to explain the diversification in the size and shape of insect eggs. Our study suggests that where eggs are laid, rather than universal allometric constants, underlies the evolution of insect egg size and shape. Size is a fundamental factor in many biological processes. The size of an 526 families and every currently described extant hexapod order24 organism may affect interactions both with other organisms and with (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). We combined this dataset with the environment1,2, it scales with features of morphology and physi- backbone hexapod phylogenies25,26 that we enriched to include taxa ology3, and larger animals often have higher fitness4. -

VKM Rapportmal

VKM Report 2016: 36 Assessment of the risks to Norwegian biodiversity from the import and keeping of terrestrial arachnids and insects Opinion of the Panel on Alien Organisms and Trade in Endangered species of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety Report from the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety (VKM) 2016: Assessment of risks to Norwegian biodiversity from the import and keeping of terrestrial arachnids and insects Opinion of the Panel on Alien Organisms and Trade in Endangered species of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety 29.06.2016 ISBN: 978-82-8259-226-0 Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety (VKM) Po 4404 Nydalen N – 0403 Oslo Norway Phone: +47 21 62 28 00 Email: [email protected] www.vkm.no www.english.vkm.no Suggested citation: VKM (2016). Assessment of risks to Norwegian biodiversity from the import and keeping of terrestrial arachnids and insects. Scientific Opinion on the Panel on Alien Organisms and Trade in Endangered species of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety, ISBN: 978-82-8259-226-0, Oslo, Norway VKM Report 2016: 36 Assessment of risks to Norwegian biodiversity from the import and keeping of terrestrial arachnids and insects Authors preparing the draft opinion Anders Nielsen (chair), Merethe Aasmo Finne (VKM staff), Maria Asmyhr (VKM staff), Jan Ove Gjershaug, Lawrence R. Kirkendall, Vigdis Vandvik, Gaute Velle (Authors in alphabetical order after chair of the working group) Assessed and approved The opinion has been assessed and approved by Panel on Alien Organisms and Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Members of the panel are: Vigdis Vandvik (chair), Hugo de Boer, Jan Ove Gjershaug, Kjetil Hindar, Lawrence R. -

Media Alert Red List2

MEDIA ALERT PORTRAITS IN RED Created in 1948, IUCN – The The Reluctant Stars of the 2002 IUCN Red List World Conservation Union brings together 72 States, 107 government agencies, 743 Gland, Switzerland, 2 October 2002 (IUCN) – IUCN – The World NGOs, 34 affiliates, and some Conservation Union brings to centre s tage some of the world’s most reluctant 10,000 scientists and experts stars through its new 2002 Red List of Threatened Species, due for official from 181 countries in a unique worldwide partnership. IUCN’s release on 8 October (details will be posted on http://iucn.org on this date). mission is to influence, Increasingly reclusive and confined to specialized places, many of these encourage and assist societies unwilling celebrities have proven difficult to trace. throughout the world to con- serve the integrity and diversity of nature and to ensure that any These stars are the world’s diverse animal and plant species inhabiting use of natural resources is assorted natural environments, from freshwater lakes, to deserts and oceans, equitable and ecologically that have found their way onto the Red List. With its last major update sustainable. released in September 2000, the Red List provides the most authoritative IUCN is the world's largest assessment of the global status of plants and animals. environmental knowledge netwo rk and has helped over 75 Some species are heading rapidly towards extinction, some are making countries to prepare and tentative recoveries, while others thought to be extinct are being implement national conservation and biodiversity strategies. rediscovered. The Ethiopian water mouse (Nilopegamys plumbeus) enters IUCN is a multi cultural, the list for the first time as Critically Endangered while the Saiga (Saiga multilingual organization with tatarica), a nomadic herding antelope of Central Asia, and the wild Bactrian 1000 staff located in 42 camel, found mainly in China, both move to Critically Endangered from lower countries. -

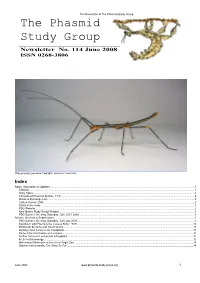

The Phasmid Study Group the Phasmid Study Group Newsletter No

The Newsletter of The Phasmid Study Group The Phasmid Study Group Newsletter No. 114 June 2008 ISSN 0268-3806 Oreophoetes peruana Copright Laurence Livermore Index News, Information & Updates .......................................................................................................................................................................................................3 Editorial.....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 Diary Dates...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 Contents of Phasmid Studies, 17(1) .......................................................................................................................................................................................4 Wants & Exchange List............................................................................................................................................................................................................4 Culture Survey 2008 ................................................................................................................................................................................................................6 Sticks in the -

Dryococelus Australis )

A bacteriological disease investigation in a captive breeding colony of Lord Howe Island Stick insects (Dryococelus australis ) Christina Cheng ORCHID: 0000-0002-2615-6957 Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree in Master of Veterinary Science. April 2017 Faculty of Veterinary and Agricultural Sciences The University of Melbourne ABSTRACT The Lord Howe Island stick insect ( Dryococelus australis) is critically endangered in the wild. Once driven to near-extinction, the species now exists within just a few captive breeding programs that have been established to conserve the species, to increase population numbers through breeding, and to support the eventual reintroduction of the species into the wild. In the current study, the bacteria Serratia marcescens was investigated as a possible cause of mortality in a captive breeding colony of D. australis housed at Melbourne Zoo. S. marcescens was isolated from both dead insects and from the environment. The prevalence of the bacteria in dead insects was estimated, and the gross pathological and histopathological changes in infected insects were characterised. Strain types of S. marcescens were characterised using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and the strain type A1 was implicated as the most likely outbreak strain associated with insect deaths. Epidemiological risk factors for mortality were also investigated, and a novel PCR test was developed to facilitate rapid detection and identification of S. marcescens . The overall findings of this research suggest that S. marcescens is a potential opportunistic pathogen of D. australis , and is associated with haemocoelomitis and death. However, high virulence was not demonstrated in infected insects under experimental conditions. Recommendations for the future management of D. -

Evolution of Flight Morphology in Stick Insects

1 2 A tale of winglets: evolution of flight morphology in stick insects 3 4 Yu Zeng1,2,†, Conner O’Malley1, Sonal Singhal1,3, Faszly Rahim4,5, 5 Sehoon Park1, Xin Chen6,7, Robert Dudley1,8 6 7 1Department of Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 92870, 8 USA 9 2Schmid College of Science and Technology, Chapman University, Orange, CA 10 92866, USA 11 3 Department of Biology, CSU Dominguez Hills, Carson, CA 90747 USA 12 4Islamic Science Institute (ISI), Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, 71800 Bandar Baru 13 Nilai, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia 14 5Centre for Insect Systematics (CIS), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 15 Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia 16 6Department of Biology, The College of Staten Island, The City University of New 17 York, NY 10314, USA 18 7Department of Biology, The Graduate School and University Center, The City 19 University of New York, NY 10016, USA 20 8Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Balboa, 21 Republic of Panama 22 23 †Corresponding author: [email protected] 24 25 1 26 27 Abstract 28 29 The evolutionary transition between winglessness and a full-winged morphology requires 30 selective advantage for intermediate forms. Conversely, repeated secondary wing 31 reductions among the pterygotes indicates relaxation of such selection. However, 32 evolutionary trajectories of such transitions are not well characterized. The stick insects 33 (Phasmatodea) exhibit diverse wing sizes at both interspecific and intersexual levels, and 34 thus provide a system for examining how selection on flight capability, along with other 35 selective forces, drives the evolution of flight-related morphology. Here, we examine 36 variation in relevant morphology for stick insects using data from 1100+ individuals 37 representing 765 species. -

The Lord Howe Island Stick Insect

The Phasmid Study Group JUNE 2012 NEWSLETTER No 128 ISSN 0268-3806 Dryococelus australis © Paul Brock (Back from extinction, see article on page 26) INDEX Page Content Page Content 2. The Colour Page 17. Orestes mouhotii 3. Editorial 19. PSG Summer Meeting 7.7.12 3. The PSG Committee 19. Make a Stick Insect Competition 4. PSG Membership Details 20. Agenda – PSG Summer Meeting 7.7.12 5. Insect Man at Prances 21. Stick Insects Survive 1m Years Without Sex 6. Insect Conservation 22. Phasma Meeting Report 22.4.12 10. Evolution & Rubus fruticosus 22. Livestock Report 11. The Newark Show 23. Saga Lout Tour, Borneo/Java 2010 Part 2 11. Phasmida Species File 24. Bug Day At Manchester Report 28.4.12 11. Errata in March Newsletter 25. Concerns Over Illegally Imported Livestock 12. PSG in Facebook 25. Phasmiden – New Book on Phasmids 12. Teddy Competition Result 25. Phasmid Wings – a Special Request 13. Development of Phasmid Species List 25. Diary Dates 16. Poem on Collecting Bramble 26. The Lord Howe Island Stick Insect It is to be directly understood that all views, opinions or theories, expressed in the pages of "The Newsletter“ are those of the author(s) concerned. All announcements of meetings, and requests for help or information, are accepted as bona fide. Neither the Editor, nor Officers of "The Phasmid Study Group", can be held responsible for any loss, embarrassment or injury that might be sustained by reliance thereon. THE COLOUR PAGE! Diapherodes gigantea (Female). Diapherodes gigantea (Male) Spiracle, drawn by Andrew Selwwood. 3rd instar’s head, drawn by Andrew Selwwood. -

2019-Delfosse Et Al.PHASMES.Pd

Catalogue des types de la collection de phasmes du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle de Paris (Insecta, Phasmatodea) Emmanuel Delfosse, Nicolas Cliquenois, Marion Depraetere, Tony Robillard To cite this version: Emmanuel Delfosse, Nicolas Cliquenois, Marion Depraetere, Tony Robillard. Catalogue des types de la collection de phasmes du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle de Paris (Insecta, Phasmatodea). Zoosystema, Museum Nationale d’Histoire Naturelle Paris, 2019, 41 (11), pp.181-235. 10.5252/zoosys- tema2019v41a11. hal-02614621 HAL Id: hal-02614621 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02614621 Submitted on 8 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. DIRECTEUR DE LA PUBLICATION : Bruno David Président du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle RÉDACTRICE EN CHEF / EDITOR-IN-CHIEF : Laure Desutter-Grandcolas ASSISTANTS DE RÉDACTION / ASSISTANT EDITORS : Anne Mabille ([email protected]), Emmanuel Côtez MISE EN PAGE / PAGE LAYOUT : Anne Mabille COMITÉ SCIENTIFIQUE / SCIENTIFIC BOARD : James Carpenter (AMNH, New York, États-Unis) Maria Marta Cigliano (Museo de La Plata, La Plata, Argentine) Henrik Enghoff (NHMD, Copenhague, Danemark) Rafael Marquez (CSIC, Madrid, Espagne) Peter Ng (University of Singapore) Norman I. Platnick (AMNH, New York, États-Unis) Jean-Yves Rasplus (INRA, Montferrier-sur-Lez, France) Jean-François Silvain (IRD, Gif-sur-Yvette, France) Wanda M.