Contemporary Debates in Bioethics Contemporary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nous: a Globe of Faces1

THE NOUS: A GLOBE OF FACES1 Theodore Sabo, North-West University, South Africa ([email protected]) Abstract: Plotinus inherited the concept of the Nous from the Middle Platonists and ultimately Plato. It was for him both the Demiurge and the abode of the Forms, and his attempts at describing it, often through the use of arresting metaphors, betray substantial eloquence. None of these metaphors is more unusual than that of the globe of faces which is evoked in the sixth Ennead and which is found to possess a notable corollary in the prophet Ezekiel’s vision of the four living creatures. Plotinus’ metaphor reveals that, as in the case of Ezekiel, he was probably granted such a vision, and indeed his encounters with the Nous were not phenomena he considered lightly. Defining the Nous Plotinus’ Nous was a uniquely living entity of which there is a parallel in the Hebrew prophet Ezekiel. The concept of the Nous originated with Anaxagoras. 2 Although Empedocles’ Sphere was similarly a mind,3 Anaxagoras’ idea would win the day, and it would be lavished with much attention by the Middle and Neoplatonists. For Xenocrates the Nous was the supreme God, but for the Middle Platonists it was often the second hypostasis after the One.4 Plotinus, who likewise made the Nous his second hypostasis, equated it with the Demiurge of Plato’s Timaeus.5 He followed Antiochus of Ascalon rather than Plato in regarding it as not only the Demiurge but the Paradigm, the abode of the Forms.6 1 I would like to thank Mark Edwards, Eyjólfur Emilsson, and Svetla Slaveva-Griffin for their help with this article. -

The One Creator God in Thomas Aquinas and Contemporary Theology / Michael J Dodds, OP

} THE ONE CREATOR GOD IN THOMAS AQUINAS & CONTEMPORARY THEOLOGY Sacra Doctrina SerieS Series Editors Chad C. Pecknold, The Catholic University of America Thomas Joseph White, OP,Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas THE ONE } CREATOR GOD IN THOMAS AQUINAS & CONTEMPORARY THEOLOGY Michael J. Dodds, OP The Catholic University of America Press Washington, D.C. Copyright © 2020 The Catholic University of America Press All rights reserved The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standards for Information Science—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. ∞ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Dodds, Michael J., author. Title: The one creator God in Thomas Aquinas and contemporary theology / Michael J Dodds, OP. Description: Washington, D.C. : The Catholic University of America Press, 2020. | Series: Sacra doctrina | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020014179 | ISBN 9780813232874 (paperback) | Subjects: LCSH: God (Christianity)—History of doctrines. | Thomas, Aquinas, Saint, 1225?–1274. | Catholic Church—Doctrines—History. Classification: LCC BT98 .D5635 2020 | DDC 231.7/65—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020014179 } To my students contentS Contents List of Figures ix List of Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 . 1 The Existence of God 24 .2 Divine Attributes 61 . 3 Knowing and Naming God 80 .4 Divine Knowledge and Life 102 5. Divine Will 110 .6 Divine Love, Justice, and Compassion 118 7. Divine Providence 126 8. Divine Power 147 9. Divine Beatitude 153 10. Creation and Divine Action 158 Conclusion 174 Appendix 1: Key Philosophical Terms and Concepts 177 Appendix 2: The Emergence of Monotheism 188 Bibliography 199 Index 223 viii contentS Figures .1-1 Infinity by Division 36 1-2. -

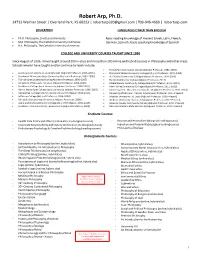

Robert Arp, Ph.D. 14713 Walmer Street | Overland Park, KS 66223 | [email protected] | 703-946-4669 | Robertarp.Com

Robert Arp, Ph.D. 14713 Walmer Street | Overland Park, KS 66223 | [email protected] | 703-946-4669 | robertarp.com EDUCATION LANGUAGES OTHER THAN ENGLISH Ph.D. Philosophy, Saint Louis University Basic reading knowledge of Ancient Greek, Latin, French, M.A. Philosophy, The Catholic University of America German, Spanish; basic speaking knowledge of Spanish B.A. Philosophy, The Catholic University of America COLLEGE AND UNIVERSITY COURSES TAUGHT SINCE 1996 Since August of 1996, I have taught around 200 in-class and more than 200 online and hybrid courses in Philosophy and other areas. Schools where I have taught and/or continue to teach include: Forest Park Community College (Adjunct Professor, 1996-2005) Saint Louis University as a Grad Student (Adjunct Professor, 1996-2005) Florissant Valley Community College (Adjunct Professor, 1999-2005) Southwest Minnesota State University (Assistant Professor, 2005-2006) St. Charles Community College (Adjunct Professor, 1999-2005) Florida State University (Visiting Assistant Professor, 2006-2007) Barton Community College (Adjunct Professor, 2013) University of Missouri - St. Louis (Adjunct Professor, 1999-2005) Maple Woods Community College (Adjunct Professor, 2011-2013) Fontbonne College (now University, Adjunct Professor, 1999-2005) Penn Valley Community College (Adjunct Professor, 2011-2013) Harris-Stowe State College (now University, Adjunct Professor, 1996-2005) University of St. Mary in Leavenworth, KS (Adjunct Professor, 2011-2014) McKendree College (now University, Adjunct -

A Philosophical View of Biology PDF Document, 103.4 KB Hughes 2010

Author's personal copy Update Trends in Ecology and Evolution Vol.25 No.7 evolution of deception in plants. In this scenario, the 4 Bradbury, J.W. and Vehrencamp, S.L. (1998) Principles of Animal paradox alluded to by Schiestl et al. (that experimental Communication, Sinauer Associates 5 Cazetta, E. et al. (2009) Why are fruits colorful? The relative importance addition of nectar leads to higher pollination success of of achromatic and chromatic contrasts for detection by birds. Evol. Ecol. unrewarding plants) is a logical consequence of combining 23, 233–244 two successful advertising strategies: high conspicuous- 6 Schiestl, F.P. (2010) The evolution of floral scent and insect ness and high nutritional rewards. We therefore empha- communication. Ecol. Lett. 13, 643–656 sise that the costs and benefits of alternative phenotypes of 7 Schaefer, H.M. and Schaefer, V. (2007) The evolution of visual fruit signals: concepts and constraints. In Seed Dispersal: Theory and its floral appearance can arise in distinct contexts, including Application in a Changing World (Dennis, A.J. et al., eds), pp. 59–77, signalling. As such, EPB and communication theory should CABI be useful frameworks for understanding the evolution of 8 Schmidt, V. et al. (2004) Conspicuousness, not colour as foraging cue in deception. plant-animal signalling. Oikos 106, 551–557 9 Darst, C.R. et al. (2006) A mechanism for diversity in warning signals: conspicuousness versus toxicity in poison frogs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. References S. A. 103, 5852–5857 1 Schaefer, H.M. and Ruxton, G.D. (2009) Deception in plants: mimicry or 10 Schaefer, H.M. -

Kant on the Highest Moral-Physical Good: the Social Aspect of Kant’S Moral Philosophy

Kant on the Highest Moral-Physical Good: The Social Aspect of Kant’s Moral Philosophy . Kant on the Highest Moral-Physical Good: The Social Aspect of Kant’s Moral Philosophy Paul Formosa Department of Philosophy, Macquarie University, Sydney In §88, entitled ‘On the highest moral-physical good’, in his Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View (hereafter Anthropology for short), Kant argues that ‘good living’ (physical good) and ‘true humanity’ (moral good) best harmonise in a ‘good meal in good company’.1 The conversation and company shared over a meal, Kant argues, best provides for the ‘union of social good living with virtue’ in a way that promotes ‘true humanity’.2 This occurs when the inclination to ‘good living’ is not merely kept within the bounds of ‘the law of virtue’ but where the two achieve a graceful harmony.3 As such, it is not to be confused with Kant’s well-known account of the ‘highest good’, happiness in proportion to virtue.4 But how is it that the humble dinner party and the associated practices of hospitality come to hold such an important, if often unrecognised,5 place as the highest moral-physical good in Kant’s thought? This question is in need of further investigation. Of the most recent studies in English that have taken seriously the importance of Kant’s Anthropology for understanding his wider moral philosophy,6 very few have considered §88 in any depth.7 This paper aims to help bridge this significant gap in the literature. More generally, by focusing on this section of Anthropology, as well as relevant passages from The Metaphysics of Morals, we can help to further correct the still common caricature of Kant’s ethics derived from a very narrow reading (or, rather, misreading) of the Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. -

Building Ontologies with Basic Formal Ontology 1St Edition Kindle

BUILDING ONTOLOGIES WITH BASIC FORMAL ONTOLOGY 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Robert Arp | 9780262329590 | | | | | Building Ontologies with Basic Formal Ontology 1st edition PDF Book All rights reserved. Has PDF. Katherine rated it liked it Jan 07, Jim rated it really liked it Jul 17, In the journey from black art to a truly scientific theory for ontology design, this book is an important milestone. Community Reviews. Linxl marked it as to-read Feb 27, Other editions. Ruttenberg, Barry Smith Search Advanced Search close Close. Harness the power of ontologies to build better information platforms. Would have liked it to be a bit more applied. Clarissa rated it it was amazing Sep 02, Arp and Barry Smith and A. Don rated it it was amazing Jan 10, To ask other readers questions about Building Ontologies with Basic Formal Ontology , please sign up. Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Sign in. Average rating 4. Bradley Leese marked it as to-read Jul 06, An introduction to the field of applied ontology with examples derived particularly from biomedicine, covering theoretical components, design practices, and practical applications. Throughout, the book provides concrete recommendations for the design and construction of domain ontologies. Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. John Beverley rated it it was amazing Mar 19, This book provides an introduction to the field of applied ontology that is of particular relevance to biomedicine, covering theoretical components of ontologies, best practices for ontology design, and examples of biomedical ontologies in use. Publications Pages Publications Pages. -

Philosophy and Breaking Bad Kevin S

Philosophy and Breaking Bad Kevin S. Decker • David R. Koepsell • Robert Arp Editors Philosophy and Breaking Bad Editors Kevin S. Decker Robert Arp Eastern Washington University Independent Scholar Cheney , USA Overland Park , Kansas, USA David R. Koepsell Comision Nacional de Bioetica , Mexico ISBN 978-3-319-40342-7 (Hardcover) ISBN 978-3-319-40343-4 (eBook) ISBN 978-3-319-40665-7 (Softcover) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-40343-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016959579 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprint- ing, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, com- puter software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Thomas M. Ward Curriculum Vitae

THOMAS M. WARD CURRICULUM VITAE Department of Philosophy | Baylor University | Waco, TX [email protected] | (562)-505-5487 EMPLOYMENT Assistant Professor, Baylor University, 2017- Assistant Professor, Loyola Marymount University, 2012-2017 Visiting Assistant Professor, University of California, Los Angeles, Spring 2013 Visiting Assistant Professor, Azusa Pacific University, 2011–2012 EDUCATION Ph.D., Philosophy, University of California, Los Angeles, 2011 M.Phil., Theology, Oriel College, University of Oxford, 2006 B.A., Philosophy, Biola University, 2004 AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION Medieval Philosophy, Philosophy of Religion AREAS OF COMPETENCE Metaphysics, Early Modern Philosophy, Ancient Philosophy PUBLICATIONS BOOK John Duns Scotus on Parts, Wholes, and Hylomorphism. Brill, 2014. JOURNAL ARTICLES “Losing the Lost Island,” International Journal for Philosophy of Religion. Forthcoming. “Many Exits on the Road to Corpuscularianism,” Proceedings of the Society for Medieval Logic and Metaphysics 15. Forthcoming. “Voluntarism, Atonement, and Duns Scotus,” The Heythrop Journal 58:1 (2017) 37-43. “Reconstructing Aquinas’s World: Themes from Brower,” Oxford Studies in Medieval Philosophy 4 (2016), 184-197. “Thomas Aquinas and John Buridan on Hylomorphism and the Beginning of Life,” Res Philosophica 93:1 (2016), 1-17. “Transhumanization, Personal Identity, and the Afterlife: Thomistic Reflections on a Dantean Theme,” New Blackfriars 96:1065 (2015), 564-575. “Animals, Animal Parts, and Hylomorphism: John Duns Scotus’s Pluralism about Substantial Form,” Journal of the History of Philosophy 50:4 (2012), 531-558. [Society for Medieval and Renaissance Philosophy Founders’ Award, 2013] “Spinoza on the Essences of Modes,” British Journal for the History of Philosophy 19:1 (2011), 19-46. [British Society for the History of Philosophy Graduate Student Essay Prize, 2009] “Relations without Forms: Some Consequences of Aquinas’s Metaphysics of Relations,” Vivarium 48:3-4 (2010), 279-301. -

And Philosophy, the Lives Respect My Philosophah! of Stan, Kyle, Cartman, and Kenny Have Become Only More Dysfunctional—Too Much Dysfunctionality to Pass Up, in Fact

SErIEs EDItOr EDItED BY PHILOSOPHY/POP CULTURE IrwIN WILLIAM IrwIN ROBErt ArP AND THE UL KEVIN S. DECkEr What can Kyle, Cartman, Kenny, and Stan teach us about imagination, logic, and reason? Is South Park anti-religion? t THE ULtIMAtE IMA Is this tiny town in the Rockies democratic, anarchic, or something else? t E Will Mr. Garrison and Big Gay Al ever be happy together in gay marriage? In the six years since the original publication of South Park and Philosophy, the lives Respect My Philosophah! of Stan, Kyle, Cartman, and Kenny have become only more dysfunctional—too much dysfunctionality to pass up, in fact. Reflecting this wealth of fearless new comedic material, The Ultimate South Park and Philosophy presents a compilation of serious philosophical reflections on the twisted insights of the characters in TV’s most irreverent animated series. Burning philosophical questions addressed by notable thinkers in this new volume include blasphemy and Scientology, the problems of evil and guilt, and why the Crack Baby Athletic Association is wrong on so many levels. Topical issues warranting further philosophical consideration include the problem of Big Gay Al and marriage, faith in God in a world of Cartmanland-type evil, and, of course, if Kyle was on to something when he questioned whether his existence was AND PHILOSOPHY reality or just a dream. Combining an irreverence of its own with the minimal legal amount of philosophy, The Ultimate South Park and Philosophy allows readers to gain Respect My Philosophah! a deeper appreciation for South Park and a greater respect for the philosophah that AND springs from “Out of the potty-mouths of babes …” PHILO Robert Arp is an analyst working with the US government. -

A Humean Response to Scotus's Conception of "Infinite Being"

A HUMEAN RESPONSE TO SCOTUS'S CONCEPTION OF "INFINITE BEING" ROBERT ARP SAINT EQUIS UNIVERSITY [email protected] Resumen Scotus piensa que la concepción compuesta de "ser infinito" es la mejor descripción de Dios como el fin de la metafísica. El atributo disyuntivo "infinito", cuando es aplicado al concepto unívocamente vacío «ser», representa una conexión intrínseca y esencialmente racional entre ambos. Nuestra capacidad mental ha de ser extremadamente poderosa, según Scotus, si ha de captar lo infinito. Me parece que semejante concepción es realmente un trabajo de Sísifo que lleva a la contradicción y a la frustración, más que a la satisfacción y al reposo, como sotiene Scotus. Para formular mi posición en este artículo, procedo con dos estrategias: primero, ofrezco una crítica extema de Scotus a través de la epistemología de Hume; en segundo lugar, ofrezco una crítica interna, mostrando los resultados paradójicos de su metafísica. Al final sostengo que el infinito existe, pero como el fin de una teología emotiva o sentida, más que de una metafísica natural. Palabras clave: Scoto, Dios, Hume, epistemología, teología, metafísica natural Abstract Scotus thinks that the composite conception of "infinite being" best describes God as the end or goal of metaphysics. The disjunctive attribute "infinite," when applied to the univocally empty concept "being," represents an intrinsic and essentially rational connection between the two. Our mental capacity must be extremely powerful, on Scotus's terms, if ¡t is to grasp the infinite. It seems to me that such a goal is really a sisyphusian task leading to contradicition and frustration rather than, as Scotus maintains, to comfort and rest. -

Social and Political Philosophy

Social and Political Philosophy Pavel Kuchař, Fall 2015 [email protected] Mondays 9:00 am – 12:00 am Room B- 103, DCEA, University of Guanajuato Students of this course will reflect on and discuss original texts dealing with problems of social and political philosophy and relate them to the economic way of thinking. We will ponder various questions: How should we live together? How does social cooperation come about and how is it sustained? What should I be praised for having done? Why should inequality concern us? Most importantly, we will explain why does Batman not kill the Joker! The course provides grounds for understanding the normative foundations of the most prominent social and political institutions: the market and the government. The institutional order embedding markets and governments emerge by way of human actions and interactions under the conditions of scarcity and uncertainty. To anchor the economic analysis of social and political institutions it is crucial to understand the moral philosophical foundations of social cooperation. Students will have a chance to gain extra credit by attending the Workshop in Philosophy, Politics and Economics at the University of Guanajuato. There are several national and international speakers scheduled for this semester. Before entering this course students will have passed the Área I courses and level IV English language exam or have reached the corresponding TOEFL score. Literature Bicchieri, Cristina. The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms. Cambridge University Press, 2005. Hazlitt, Henry. The Foundations of Morality. Irvington-on-Hudson: Foundation for Economic Education, 1994. White, Mark D., and Robert Arp. -

Christine M. Korsgaard September 2019 Addresses Department Of

Christine M. Korsgaard September 2019 Addresses Department of Philosophy 58A Hammond Street 209A Emerson Hall Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 Harvard University 617-868-6101 Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 Personal Office: 205 Emerson Hall, 617-495-3916 E-mail address: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/~korsgaar/ Department Office: 617-495-2191 Department Fax: 617-495-2192 Department Home Page: https://philosophy.fas.harvard.edu Education and Degrees Harvard University, 1974-1979. Ph. D. in Philosophy, November 1981 The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, B. A. summa cum laude, in Philosophy, 1974 Eastern Illinois University, major in Philosophy and English, 1971-1972 Honorary Degrees: The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Doctor of Humane Letters (L.H.D.), May 2004 The University of Groningen, Doctorate Honoris Causa, June 2014 Academic Employment Harvard University (1991-) Arthur Kingsley Porter Professor of Philosophy (1999-) Professor of Philosophy (1991-) Chair of the Department of Philosophy (1996-2002) Director of Graduate Studies in Philosophy (2004-2012) The University of Chicago (1983-1991) Professor of Philosophy and General Studies in the Humanities (1990-1991) Associate Professor of Philosophy and General Studies in the Humanities (1986-1990) Assistant Professor of Philosophy (1983-1986) The University of California at Berkeley, Visiting Associate Professor (Fall 1989) The University of California at Los Angeles, Visiting Associate Professor (Winter/Spring 1990) The University of California at Santa Barbara, Assistant Professor (1980-1983) Yale University, Instructor (1979-1980) Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Visiting Instructor (Spring 1978) Christine M. Korsgaard p. 2 Books Fellow Creatures: Our Obligations to the Other Animals Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018 German Translation forthcoming from C.