The Nous: a Globe of Faces1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medieval Western Philosophy: the European Emergence

Cultural Heritage and Contemporary Change Series I, Culture and Values, Volume 9 History of Western Philosophy by George F. McLean and Patrick J. Aspell Medieval Western Philosophy: The European Emergence By Patrick J. Aspell The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy 1 Copyright © 1999 by The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Gibbons Hall B-20 620 Michigan Avenue, NE Washington, D.C. 20064 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Aspell, Patrick, J. Medieval western philosophy: the European emergence / Patrick J. Aspell. p.cm. — (Cultural heritage and contemporary change. Series I. Culture and values ; vol. 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Philosophy, Medieval. I. Title. III. Series. B721.A87 1997 97-20069 320.9171’7’090495—dc21 CIP ISBN 1-56518-094-1 (pbk.) 2 Table of Contents Chronology of Events and Persons Significant in and beyond the History of Medieval Europe Preface xiii Part One: The Origins of Medieval Philosophy 1 Chapter I. Augustine: The Lover of Truth 5 Chapter II. Universals According to Boethius, Peter Abelard, and Other Dialecticians 57 Chapter III. Christian Neoplatoists: John Scotus Erigena and Anselm of Canterbury 73 Part Two: The Maturity of Medieval Philosophy Chronology 97 Chapter IV. Bonaventure: Philosopher of the Exemplar 101 Chapter V. Thomas Aquinas: Philosopher of the Existential Act 155 Part Three: Critical Reflection And Reconstruction 237 Chapter VI. John Duns Scotus: Metaphysician of Essence 243 Chapter -

St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas on the Mind, Body, and Life After Death

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Williams Honors College, Honors Research The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors Projects College Spring 2020 St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas on the Mind, Body, and Life After Death Christopher Choma [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects Part of the Christianity Commons, Epistemology Commons, European History Commons, History of Philosophy Commons, History of Religion Commons, Metaphysics Commons, Philosophy of Mind Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Recommended Citation Choma, Christopher, "St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas on the Mind, Body, and Life After Death" (2020). Williams Honors College, Honors Research Projects. 1048. https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/1048 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors College at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The University of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Williams Honors College, Honors Research Projects by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 1 St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas on the Mind, Body, and Life After Death By: Christopher Choma Sponsored by: Dr. Joseph Li Vecchi Readers: Dr. Howard Ducharme Dr. Nathan Blackerby 2 Table of Contents Introduction p. 4 Section One: Three General Views of Human Nature p. -

History of Philosophy Outlines from Wheaton College (IL)

Property of Wheaton College. HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY 311 Arthur F. Holmes Office: Blanch ard E4 83 Fall, 1992 Ext. 5887 Texts W. Kaufman, Philosophical Classics (Prentice-Hall, 2nd ed., 1968) Vol. I Thales to Occam Vol. II Bacon to Kant S. Stumpf, Socrates to Sartre (McGraW Hill, 3rd ed., 1982, or 4th ed., 1988) For further reading see: F. Copleston, A History of Philosophy. A multi-volume set in the library, also in paperback in the bookstore. W. K. C. Guthrie, A History of Greek Philosophy Diogenes Allen, Philosophy for Understanding Theology A. H. Armstrong & R. A. Markus, Christian Faith and Greek Philosophy A. H. Armstrong (ed.), Cambridge History of Later Greek and Early Medieval Philosophy Encyclopedia of Philosophy Objectives 1. To survey the history of Western philosophy with emphasis on major men and problems, developing themes and traditions and the influence of Christianity. 2. To uncover historical connections betWeen philosophy and science, the arts, and theology. 3. To make this heritage of great minds part of one’s own thinking. 4. To develop competence in reading philosophy, to lay a foundation for understanding contemporary thought, and to prepare for more critical and constructive work. Procedure 1. The primary sources are of major importance, and you will learn to read and understand them for yourself. Outline them as you read: they provide depth of insight and involve you in dialogue with the philosophers themselves. Ask first, What does he say? The, how does this relate to What else he says, and to what his predecessors said? Then, appraise his assumptions and arguments. -

Aristotle on Thinking ( Noêsis )

Aristotle on Thinking ( Noêsis ) The Perception Model DA III.4-5. Aristotle gives an account of thinking (or intellect—noêsis ) that is modeled on his account of perception in Book II. Just as in perception, “that which perceives” ( to aisthêtikon ) takes on sensible form (without matter), so in thinking “that which thinks” ( to noêtikon ) takes on intelligible form (without matter). Similarly, just as in perception, the perceiver has the quality of the object potentially, but not actually, so, too, in understanding, the intellect is potentially (although not actually) each of its objects. Problem This leaves us with a problem analogous to the one we considered in the case of perception. There we wondered how the perceiver of a red tomato could be potentially (but not actually) red (prior to perceiving it), and yet become red (be actually red) in the process of perceiving it. Here the question is how the intellect that thinks about a tomato (or a horse) is potentially a tomato (or a horse), and then becomes a tomato (or a horse) in the process of thinking about it. The problem about thinking seems more severe: for although there is a sense in which the perceiver becomes red (the sense organ becomes colored red), there does not seem to be a comparable sense in which the intellect becomes a tomato (or a horse). (1) there is no organ involved, and (2) there does not seem to be room in there for a tomato (let alone a horse). The Differences from Perception As we will see, there are important differences between perceiving and understanding, beyond the fact the one involves taking on perceptible form and the other intelligible form. -

![1 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, Summa Theologiae [1272], 2.1, 9780895267054 Gateway Trans](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9268/1-aquinas-treatise-on-law-summa-theologiae-1272-2-1-9780895267054-gateway-trans-509268.webp)

1 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, Summa Theologiae [1272], 2.1, 9780895267054 Gateway Trans

PROGRAM OF LIBERAL STUDIES JUNIOR READING LIST PLS 33101, SEMINAR III Students are asked to purchase the indicated editions. With Instructor’s permission other editions may be used. Students are expected to have done the first reading when coming to the first meeting of the seminar. 1 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, Summa Theologiae [1272], 2.1, 9780895267054 Gateway trans. Parry, Questions 90-93 2 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, Summa Theologiae, Questions 94-97 3 Aquinas, On Faith, Summa Theologiae 2.2, trans. Jordan, 9780268015039 Notre Dame Prologue-Pt 2-2, Quest 1, 2, (Art 1-4, 10), 3, 4, (Art 3-5) 4 Aquinas, On Faith, Summa Theologiae, Questions 6, 10 5 Dante, The Inferno, The Divine Comedy [1321], 9780553213393 Bantam Cantos 1-17, trans. Mandelbaum 6 Dante, The Inferno, Cantos 18-34 7 Dante, Purgatorio, Cantos 1-18, trans. Mandelbaum 9780553213447 Bantam 8 Dante, Purgatorio, Cantos 19-33 9 Dante, Paradiso, Cantos 1-17, trans. Mandelbaum 9780553212044 Bantam 10 Dante, Paradiso, Cantos 18-33 11 Petrarch, "Ascent of Mount Ventoux" [1336] and "On His 9780226096049 Chicago Own Ignorance and That of Many Others" [1370], trans Nachod, in The Renaissance Philosophy of Man, ed. Cassirer, Kristeller, Randall 12 Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales [1387-1400], trans. Coghill, "Prologue," 9780140424386 Penguin "Knight’s Tale," "Millers Tale," and "Nun’s Priest Tale" (each tale with accompanying prologues and epilogues where appropriate) 13 Chaucer, Canterbury Tales, "Pardoner’s Tale," "Wife of Bath’s Tale," "The Clerk’s Tale," "Franklin’s Tale," and "Retraction" (each tale with accompanying prologues and epilogues where appropriate) 14 Julian of Norwich, Showings [1393], trans. -

The One Creator God in Thomas Aquinas and Contemporary Theology / Michael J Dodds, OP

} THE ONE CREATOR GOD IN THOMAS AQUINAS & CONTEMPORARY THEOLOGY Sacra Doctrina SerieS Series Editors Chad C. Pecknold, The Catholic University of America Thomas Joseph White, OP,Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas THE ONE } CREATOR GOD IN THOMAS AQUINAS & CONTEMPORARY THEOLOGY Michael J. Dodds, OP The Catholic University of America Press Washington, D.C. Copyright © 2020 The Catholic University of America Press All rights reserved The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standards for Information Science—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. ∞ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Dodds, Michael J., author. Title: The one creator God in Thomas Aquinas and contemporary theology / Michael J Dodds, OP. Description: Washington, D.C. : The Catholic University of America Press, 2020. | Series: Sacra doctrina | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020014179 | ISBN 9780813232874 (paperback) | Subjects: LCSH: God (Christianity)—History of doctrines. | Thomas, Aquinas, Saint, 1225?–1274. | Catholic Church—Doctrines—History. Classification: LCC BT98 .D5635 2020 | DDC 231.7/65—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020014179 } To my students contentS Contents List of Figures ix List of Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 . 1 The Existence of God 24 .2 Divine Attributes 61 . 3 Knowing and Naming God 80 .4 Divine Knowledge and Life 102 5. Divine Will 110 .6 Divine Love, Justice, and Compassion 118 7. Divine Providence 126 8. Divine Power 147 9. Divine Beatitude 153 10. Creation and Divine Action 158 Conclusion 174 Appendix 1: Key Philosophical Terms and Concepts 177 Appendix 2: The Emergence of Monotheism 188 Bibliography 199 Index 223 viii contentS Figures .1-1 Infinity by Division 36 1-2. -

IGNATIAN CURRENTS Dr. Elizabeth Dreye

SEPTEMBER 2012 VOL III NO 2 A WORD FROM THE DIRECTOR CALLED AND SENT SPIRITUAL FORMATION With the coming of fall, we begin another ministry year. We PROGRAM take as our inspiration Ignatius Loyola, the “Imperfect Living Prayer: My Life in God. This 6-week retreat-in-daily Pilgrim,” who challenges us to radical trust in Christ whose life, a module of the Called and Sent Program, will begin on mission we embrace. Here is where you will find us serving September 5 th and continue through October 10 th at Blessed Christ’s mission in northeast Ohio: Trinity Parish. Please pray for the 8-member team and the 36 parishioners who will be attending this retreat. Ignatian Spirituality: Grounding for Life and Leadership. Plans continue as we look forward to taking this 7-part module to the St. Ignatius High School Board of Directors. On August 30 th , Sharon Bramante, Pat Cleary-Burns and Eileen Biehl joined me for our first Round Table brainstorming and planning group in support of the design and development of two new modules, Discernment and Decision Making and The Christian at Work in the World. Both modules will be piloted in the spring. COMING THIS MONTH … IGNATIAN CURRENTS Praying with St. Ignatius Retreat Leaders – August 2012 Dr. Elizabeth Dreyer Praying with St. Ignatius Parish Retreats. On August 18 th , Register Now! Come and Bring a Friend! three leadership teams were commissioned to take the th Friday, September 14 retreat to three sites: Assumption Parish (Broadview 7:00 – 9:00 p.m. (Coffee and Conversation – 6:30 p.m.) Heights) will host this 8-week retreat on Tuesdays beginning September 18 th . -

The Interior Castle: the Mystical Wisdom of St

A NOW YOU KNOW MEDIA STUDY GUIDE Exploring The Interior Castle: The Mystical Wisdom of St. Teresa of Avila Presented by Professor Keith Egan, Ph.D. E X P L O R I N G THE INTERIOR CASTLE STUDY GUIDE Now You Know Media Copyright Notice: This document is protected by copyright law. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. You are permitted to view, copy, print, and distribute this document (up to seven copies), subject to your agreement that: Your use of the information is for informational, personal and noncommercial purposes only. You will not modify the documents or graphics. You will not copy or distribute graphics separate from their accompanying text and you will not quote materials out of their context. You agree that Now You Know Media may revoke this permission at any time and you shall immediately stop your activities related to this permission upon notice from Now You Know Media. WWW.NOWYOUKNOWMEDIA.COM / 1 - 8 0 0 - 955- 3904 / © 2 0 1 4 E X P L O R I N G THE INTERIOR CASTLE STUDY GUIDE Prof. Keith Egan, Ph.D. Ph.D., University of Cambridge Former President of the Carmelite Institute r. Keith J. Egan is the Aquinas Chair in Catholic Theology Emeritus at Saint Mary’s College where, in 1984, he founded F the college’s Center for Spirituality. He is also an adjunct professor of theology at the University of Notre Dame and former president of the Carmelite Institute (2007–2012). Dr. Egan’s doctorate is from the University of Cambridge, England. He lectures widely and has published extensively on Christian spirituality and mysticism as well as on Carmelite spirituality to audiences in North America, Ireland, England and Rome. -

73 the Pupils of Philo of Larissa and Philodemus' Stay in Sicily (Pherc. 1021, Col. Xxxiv 6-19)

This article provides a new edition of a passage from Philodemus’ Index Academicorum THE PUPILS OF PHILO (PHerc. 1021, col. XXXIV 6-19), in which pupils of Philo of Larissa are listed. Several OF LARISSA AND new reading allow for a better understanding of the content and rendering of this list, PHILODEMUS’ STAY one of which might even corroborate the hypothesis that Philodemus sojourned in Sicily. IN SICILY (PHERC. 1021, Keywords: Philo of Larissa, Heraclitus of Tyre, Philodemus, Sicily, Historia Academi- COL. XXXIV 6-19) corum Shortly before the end of his Index Academicorum Philodemus informs us about the life of Philo of Larissa (PHerc. 1021, coll. XXXIII f.).1 Notwithstanding KILIAN FLEISCHER its fragmentary state, the passage is highly valuable, since it preserves much otherwise unattested information on Philo and allows us to reconstruct to a certain extent his personal and philosophical development. The passage dealing with Philo ends with a list of pupils that was long thought to include the pupils of Antiochus of Ascalon. Puglia was the first to argue convincingly that the names listed represent pupils of Philo, not of Antiochus.2 In this contribution I will present a new edition of this list (col. XXXIV 6-19), based on autopsy and for the first time exploiting the multispectral digital images, I would like to express my gratitude to Nigel retta da M. GIGANTE, vol. XII (Napoli 1991); 1902 = S. MEKLER, Academicorum philoso- Wilson, David Blank, Tobias Reinhardt, Tizia- FLEISCHER 2014 = K. FLEISCHER, Der Akademi- phorum index Herculanensis (Berlin 1902); no Dorandi and Holger Essler for their advice ker Charmadas in Apollodors Chronik (PHerc. -

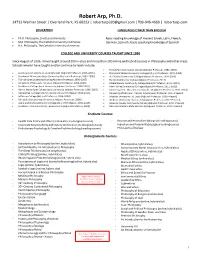

Robert Arp, Ph.D. 14713 Walmer Street | Overland Park, KS 66223 | [email protected] | 703-946-4669 | Robertarp.Com

Robert Arp, Ph.D. 14713 Walmer Street | Overland Park, KS 66223 | [email protected] | 703-946-4669 | robertarp.com EDUCATION LANGUAGES OTHER THAN ENGLISH Ph.D. Philosophy, Saint Louis University Basic reading knowledge of Ancient Greek, Latin, French, M.A. Philosophy, The Catholic University of America German, Spanish; basic speaking knowledge of Spanish B.A. Philosophy, The Catholic University of America COLLEGE AND UNIVERSITY COURSES TAUGHT SINCE 1996 Since August of 1996, I have taught around 200 in-class and more than 200 online and hybrid courses in Philosophy and other areas. Schools where I have taught and/or continue to teach include: Forest Park Community College (Adjunct Professor, 1996-2005) Saint Louis University as a Grad Student (Adjunct Professor, 1996-2005) Florissant Valley Community College (Adjunct Professor, 1999-2005) Southwest Minnesota State University (Assistant Professor, 2005-2006) St. Charles Community College (Adjunct Professor, 1999-2005) Florida State University (Visiting Assistant Professor, 2006-2007) Barton Community College (Adjunct Professor, 2013) University of Missouri - St. Louis (Adjunct Professor, 1999-2005) Maple Woods Community College (Adjunct Professor, 2011-2013) Fontbonne College (now University, Adjunct Professor, 1999-2005) Penn Valley Community College (Adjunct Professor, 2011-2013) Harris-Stowe State College (now University, Adjunct Professor, 1996-2005) University of St. Mary in Leavenworth, KS (Adjunct Professor, 2011-2014) McKendree College (now University, Adjunct -

Numenius and the Hellenistic Sources of the Central Christian Doctrine

! Numenius and the Hellenistic Sources ! of the Central Christian Doctrine Marian Hillar Center for Philosophy and Socinian Studies Houston, TX 77004 Paper published in A Journal from the Radical Reformation. A testimony to Biblical Unitarianism. Vol. 14, No.! 1, Spring 2007, pp. 3-31. Quis obsecro, nisi penitus amens logomachias has sine risu toleraret? Nec in Thalmud, nec in Alchoran, sunt tam horrendae blasfemiae. Haec nos hactenus audire ita sumus alsuefacti, ut nihil miremur. Futurae vero generationes stupenda haec iudicabunt. Stupenda sunt vere, plusquam ea daemonum inventa, quae Valentinianis tribuit Irenaeus. I implore you, who in his sane mind could tolerate such logomachias without bursting into laughter? Not in the Talmud, nor in the Qu’ran can one find such horrendous blasphemies. But we are accustomed to hear them to the point that nothing astonishes us. Future generations will judge them obscure. Indeed, they are obscure, much more than the diabolic inventions which Irenaeus attributed to the Valentinians. ! Michael Servetus Christianismi Restitutio, De Trinitate, lib. I. p. 46. Si locum mihi aliquem ostendas, quo verbum illud filius olim vocetur, fatebor me victum. Christianismi Restitutio, If you show me a single passage in which the Son was called the Word, I will give up. Michael Servetus, Christianismi Restitutio, De Trinitate, lib. III p. 108. ! Abstract This paper attempts to explain the sources of the central Christian doctrine about the nature of deity. We can trace a continuous line of thought from the Greek philosophy to the development of the doctrine of the Trinity. The first Christian doctrine was developed by Justin Martyr (114-165 C.E.). -

The Ideas As Thoughts of God

Études platoniciennes 8 | 2011 Les Formes platoniciennes dans l'Antiquité tardive The Ideas as thoughts of God John Dillon Publisher Société d’Études Platoniciennes Electronic version Printed version URL: http:// Date of publication: 1 November 2011 etudesplatoniciennes.revues.org/448 Number of pages: 31-42 DOI: 10.4000/etudesplatoniciennes.448 ISSN: 2275-1785 Brought to you by Fondation Maison des sciences de l'homme Electronic reference John Dillon, « The Ideas as thoughts of God », Études platoniciennes [Online], 8 | 2011, Online since 16 December 2014, connection on 24 May 2017. URL : http://etudesplatoniciennes.revues.org/448 ; DOI : 10.4000/etudesplatoniciennes.448 © Société d’Études platoniciennes The Ideas as Thoughts of God John Dillon Xenocrates’ Nous-Monad The precise origin of the concept of the Platonic Forms, or Ideas, as thoughts of God is a long-standing puzzle in the history of Platonism, which I am on record as dismissing somewhat brusquely in various works.1 I am glad to have an opportunity to return to it now, in this distinguished company.2 I propose to begin my consideration of it on this occasion by returning to the seminal article of Audrey Rich, published in Mnemosyne back in 1954.3 As you may recall, Rich’s thesis in that article was that the concept arose, whenever it arose – sometime in the early Hellenistic age, was her guess – as a reaction to Aristotle’s concept of the Unmoved Mover of Met. Lambda as an intellect thinking itself, and “a desire to reconcile the Theory of Ideas with the Aristotelian doctrine of immanent form” (p.