Signals for Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AGENDA COMMITTEE on FINANCE Meeting

AGENDA COMMITTEE ON FINANCE Meeting: 1:45 p.m., Tuesday, July 18, 2017 Glenn S. Dumke Auditorium Peter J. Taylor, Chair John Nilon, Vice Chair Jane W. Carney Adam Day Hugo N. Morales Jorge Reyes Salinas Lateefah Simon Consent Approval of Minutes of the Meeting of May 23, 2017 1. Approval to Issue Trustees of the California State University Systemwide Revenue Bonds and Related Debt Instruments for an Auxiliary Project at California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, Action Discussion 2. Final Approval of the University Glen, Phase 2 Housing Project at California State University Channel Islands, Action 3. Auxiliary Organizations, Information 4. 2017-2018 Final Budget, Information MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE COMMITTEE ON FINANCE Trustees of the California State University Office of the Chancellor Glenn S. Dumke Conference Center 401 Golden Shore Long Beach, California May 23, 2017 Members Present Peter Taylor, Chair Debra Farar, Vice Chair Jane W. Carney Adam Day Jean P. Firstenberg Hugo N. Morales Timothy P. White, Chancellor Trustee Peter Taylor called the meeting to order. Public Comments Several speakers representing the California State University Employees Union, State Employees Trades Council, and California Faculty Association provided public comment relating to the need for increased funding for employee compensation and opportunities for advancement. Approval of Minutes The minutes of the March 22, 2017 meeting were approved as submitted. Appointment of Three Members to the Fullerton Arboretum Commission Trustee Taylor presented agenda item one as a consent action item. The committee recommended approval of the proposed resolution (RFIN 05-17-04). Approval to Issue Trustees of the California State University Systemwide Revenue Bonds and Related Debt Instruments for Projects at California State University, Los Angeles and San Diego State University Two campus projects were presented for approval to issue CSU Systemwide Revenue Bonds. -

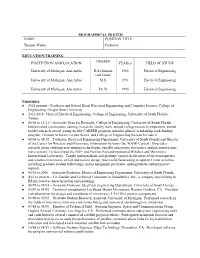

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH NAME POSITION TITLE Thomas Weller Professor

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH NAME POSITION TITLE Thomas Weller Professor EDUCATION/TRAINING INSTITUTION AND LOCATION DEGREE YEAR(s) FIELD OF STUDY University of Michigan, Ann Arbor B.S.(Summa 1988 Electrical Engineering cum laude) University of Michigan, Ann Arbor M.S. 1991 Electrical Engineering University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Ph. D. 1995 Electrical Engineering Experience 2018-present – Professor and School Head, Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, College of Engineering, Oregon State University 2012-2018 Chair of Electrical Engineering, College of Engineering, University of South Florida, Tampa. 05/08 to 11/11 – Associate Dean for Research, College of Engineering, University of South Florida. Implemented a non-tenure earning (research) faculty track, annual college research symposium, annual faculty research award, young faculty CAREER program, interdisciplinary scholarship seed-funding program, Eminent Scholars Lecture Series, and College of Engineering Research Council. 08/06 to 08/18 – Professor, Electrical Engineering Department, University of South Florida and Director of the Center for Wireless and Microwave Information Systems (the WAMI Center). Directed a research group studying new antenna technologies, tunable microwave electronics and microwave/mm- wave sensors. Co-developed the NSF- and Hewlett Packard-sponsored Wireless and Microwave Instructional Laboratory. Taught undergraduate and graduate courses in the areas of electromagnetics and wireless/microwave circuit and system design. Successful fundraising to support Center activities including graduate student fellowships, major equipment purchases, undergraduate student project support. 05/01 to 2006 – Associate Professor, Electrical Engineering Department, University of South Florida. 4/01 to present – Co-founder and Technical Consultant to Modelithics, Inc., a company specializing in RF/microwave characterization and modeling. 08/95 to 05/01 – Assistant Professor, Electrical Engineering Department, University of South Florida. -

Layout Program

Voices Raised The Silver Anniversary of Radio Bilingüe’s National News and Information Service Voces Vqoicuese R aSised uenan 1985 ~ 2010 The Silver Anniversary of Radio Bilingüe’s National News and Information Service 25 years ~ Noticiero Latino – Breaking news daily for Latinos nationwide 15 years ~ Línea Abierta – National talk show connecting audiences and newsmakers 30 Years ~ Radio Bilingue – Public media by Latinos for Latinos Friday, May 21, 2010 6 -9 pm Oakland Asian Cultural Center Performances by Mariachi Colima de Javier Magallón Mariachi Femenil Orgullo Mexicano Remarks by Special Guest ~ the Honorable Cruz Reynoso Tribute to Miguel Martínez ~ “Father of the Mariachi Trumpet” Also celebrating the opening of new national studios in Downtown Oakland 405 14th Street, Suite 414 Oakland, CA 94612 Event supported in part by the National Endowment for the Arts Celebrating our Messengers ¡Bienvenidos! What better way to mark this moment on the journey of Radio Bilingüe than to cel - ebrate our journalists and our mariachi musicians – the messengers who have raised the voices and told the stories of Mexicanos and Latinos when no one else would? With artfulness, precision and dedication, the messengers capture and bring to air our most important life is - sues and community concerns. Our stories are their stories. Radio Bilingüe tonight celebrates the building and sustaining of the first and only national Span - ish language news and information service for the public broadcasting system – now reaching audiences across the U.S., Mexico and other nations. And, we proudly carry on our leadership in the modern mariachi movement to foster the tradition and ensure this music of the people stays with the people. -

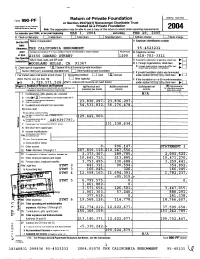

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue S°""" Nato : The organization may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting 2004 For calendar year 2004, or tax year beginning MAR 1 , 2004 , and ending ., , G Check all that apply. Initial return Final return Amended return Address change Name Use the IRS Name of organization Employer identification number label otherwise, HB CALIFORNIA ENDOWMENT 95-4523232 print Number and street (or P 0 box number d mad is not delivered to street address) Foom/swte B Telephone number ortype. 1650 OXNARD STREET 1200 I 818-703-3311 See Specifi City or town, state, and ZIP code C K exemption application is pending, check here ,U Instructions . OODLAND HILLS, CA 91367 D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Mo.= 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, , H Check type of organization Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation check here and attach computation trust Other taxable private foundation Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable E-] E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: Cash -Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here 10 (from Part 1J, col. (c), line 16) E~] Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination 1$ 3 , 7 2 9 , 5 71 , 5 2 4 . (per t, column (d) must be on cash basis under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here 1 Part I Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net (d) Disbursements (The total of amounts in columns (b), (c), and (d) may not for charitable pure ses necessarily equal me amounts m column (a)) expenses per books income income (cash basis on] 1 Contributions, gifts, grants, etc_, received N/A 2 Check, X d the foundation a not required to attach Sch B int er es t and temporary 3 investment s 23,836,297 . -

National Heritage Fellowships

2020 NATIONAL HERITAGE FELLOWSHIPS NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS I 2020 NATIONAL HERITAGE FELLOWSHIPS Birchbark Canoe by Wayne Valliere Photo by Tim Frandy COVER: “One Pot Many Spoons” beadwork by Karen Ann Hoffman Photo by James Gill Photography CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE ACTING CHAIRMAN ...........................................................................................................................................................................................4 MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR .............................................................................................................................................................................................................5 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE NEA NATIONAL HERITAGE FELLOWSHIPS .........................................................................................................................................6 2020 NATIONAL HERITAGE FELLOWS William Bell .................................................................................................................................................................................8 Soul Singer and Songwriter > ATLANTA, GA Onnik Dinkjian ....................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Armenian Folk and Liturgical Singer > FORT LEE, NJ Zakarya and Naomi Diouf ............................................................................................................................................ -

Agenda March 24, 2020**

AMENDED TRUSTEES OF THE CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY California State University Office of the Chancellor—Glenn S. Dumke Auditorium* 401 Golden Shore Long Beach, CA 90802 Agenda March 24, 2020** Time** Committee Location1 SUNDAY, MARCH 22, 2020 5:00 p.m. Call to Order 5:00 p.m. Board of Trustees—Closed Session Westin Long Beach Executive Personnel Matters Government Code §11126(a)(1) MONDAY, MARCH 23, 2020 8:00 a.m. Board of Trustees—Closed Session Westin Long Beach Executive Personnel Matters Government Code §11126(a)(1) **Items noted above with a strikethrough have been canceled. The meeting will take place entirely virtually via teleconference on Tuesday, March 24, 2020 only. 1 All committees meet in the Dumke Auditorium unless otherwise noted. The March 24, 2020 meeting will take place entirely virtually via teleconference. *PLEASE NOTE: Due to the Governor’s proclamation of a State of Emergency resulting from the threat of COVID-19, and pursuant to the Governor’s Executive Order N-25-20 issued on March 12, 2020, all members of the Board of Trustees may participate in this meeting remotely, either by telephonic or video conference means. Out of consideration for the health, safety and well-being of the members of the public and the Chancellor’s Office staff, the Dumke Auditorium will not be open to the public during the meeting, and no Trustees or staff will be present in the Auditorium. Members of the public may offer public comment pursuant to the revised published protocol for “Addressing the Board of Trustees” as noted in this agenda. -

A Guide to the Sandra Cisneros Papers, 1954-2014 Collection 123

A Guide to the Sandra Cisneros Papers, 1954-2014 Collection 123 Descriptive Summary Creator: Sandra Cisneros Title: The Sandra Cisneros Papers Dates: 1954-2014 Abstract: The Sandra Cisneros Papers span 1954-2014 and are divided into twenty- seven series that document her entire life and literary career up until the archives acquisition in 2015. The bulk of the archive consists of Cisneros’ writings, correspondence, photographs, publicity, and letters from readers. Many other aspects of her career are represented through professional papers, publishing, awards, and organizational affiliations such as the Alfred Cisneros del Moral Foundation, the Macondo Foundation, and Los MacArturos. The 1997-1998 controversy over her purple house in San Antonio is also well documented. Identification: Collection 123 Extent: 305 boxes plus artifacts and framed items; (approx. 230 linear feet) Language: English, Spanish Repository: The Wittliff Collections, Texas State University 1 Administrative Information Access Restrictions Some letters have been separated into a “restricted” series. There will be no access to this material until 2067 unless the restriction is lifted before then. Additionally, access to computer files and some audio and video are on a case-by-case basis. Please contact the archives staff for information about access. Preferred Citation Sandra Cisneros Papers, The Wittliff Collections, Texas State University Acquisition Information Purchase, 2015 Processing Information Processed in 2017 by Katie Salzmann, with assistance from Elizabeth Moeller, Madelyn Patlan, Carol Alvarez, and Audrey Johnston 2 Sandra Cisneros Timeline 1954 Born December 20 in Chicago to upholsterer Alfredo Cisneros de Moral and Elvira Cordero Anguiano. She is the third of seven children, and their only daughter. -

Comings and Goings and Meet with Alumni

JOHN HARVARD’S JOURNAL rent goals include decreasing reliance on (“When I see them surviving out on the that link. Every March, Morales attends public funding (the Corporation for Pub- street,” he says, “it’s an inspiration to me the station’s annual mariachi festival, a lic Broadcasting provides 27 percent of how a≠ectionate they are toward humans fundraiser that draws thousands of peo- the budget, much less than it used to); despite the challenges they face.”) He has ple and is the longest-running event of its gaining a foothold in the Los Angeles no children, and recently moved in with kind in the nation. “I think it is a good media market; filing for spectrum space his companion, Amy Kitchener, a folk- thing for immigrants, regardless of where to become the only public-radio outlet for lorist for the State of California. they came from, to maintain their lan- Latinos in Texas; and developing a na- Spare time has often been spent visit- guage and culture,” he says. “And it is also tional Spanish-language Latino news and ing his parents. Although Rafael Morales, important for all American immigrants to information service for digital public- who died last December, had lived and be a part of the mainstream, in order to radio channels in the United States. worked in America for more than half his function and be a part of this wonderful life, he wished to return to Mexico after country, which is America.” (He himself His honors include the 1999 Edward R. death, so his wife and son made the trip filed for citizenship the day he turned 18, Murrow Award from the Corporation for to Oaxaca in January, burying Rafael’s because he wanted “a voice in my new Public Broadcasting for his “visionary” ashes in the Tequixtepec graveyard next adopted country.”) expansion of public radio and commit- to his parents. -

AGENDA COMMITTEE on AUDIT Meeting

AGENDA COMMITTEE ON AUDIT Meeting: 10:05 a.m., Wednesday, January 31, 2018 Glenn S. Dumke Auditorium Douglas Faigin, Chair Hugo N. Morales, Vice Chair Silas H. Abrego Lillian Kimbell Peter J. Taylor Consent 1. Approval of Minutes of the Meeting of November 8, 2017, Action 2. Status Report on Current and Follow-up Internal Audit Assignments, Information Discussion 3. Calendar Year 2018 Plan for Audits, Advisory Services, and Investigations, Action 4. Report of the Systemwide Financial Statements and Single Audit of Federal Awards Including the Report to Management, Information Action Item Agenda Item 1 January 29-31, 2018 Page 1 of 2 MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF COMMITTEE ON AUDIT Trustees of the California State University Office of the Chancellor Glenn S. Dumke Conference Center 401 Golden Shore Long Beach, California November 8, 2017 Members Present Hugo N. Morales, Vice Chair Silas H. Abrego Lillian Kimbell Peter J. Taylor Rebecca Eisen, Chair of the Board Timothy P. White, Chancellor Trustee Douglas Faigin called the meeting to order. Approval of Minutes The minutes of September 20, 2017, were approved as submitted. Status Report on Current and Follow-up Internal Audit Assignments With the concurrence of the committee, Trustee Faigin presented agenda item 1 as a consent information item. Report on Implementation of the New Organization Structure of the Office of Audit and Advisory Services Mr. Larry Mandel, vice chancellor and chief audit officer, provided a status update on the new organization structure, which was developed in response to recommendations contained in the 2014 quality assurance review of the Office of Audit and Advisory Services. -

2009 Annual Report

PUBLIC RA DIO CAPITAL Building Public Media for the Future Annual Report 2009 10.5 million people gained access to new public radio signals through PRC transactions An estimated 600,000 public radio listeners got their signal from a station acquired with PRC’s help* 336,000 people benefited from a PRC transaction that kept their public radio station on the air PRC directed more than 93 percent of its income to program expenses that advance our mission 25 clients received PRC services By the in 20 different states from Alaska to Florida 19 individuals, families and Numbers foundations became senior investors in the Public Radio Fund 2009 7 public radio organizations applied for Public Radio Fund loans 5 grants provided $723,000 to support the work of PRC 1 public radio organization (North Texas Public Broadcasting) borrowed $2.5 million from the Fund CONTENTS 1 Message from the board chairman 2 Message from the managing directors and co-founders 3 Client transactions 4 Preserving and strengthening classical music in Boston 6 Los Angeles helps write the next chapter for public media 8 New Horizons: A Native Public Radio Station Impact Measurement Instrument 10 KERA Launches KXT 91.7 public music radio 11 Miami University and Cincinnati Public Radio preserve access to critical news, information 12 Public radio’s share in the top 25 markets 13 Public Radio Fund 14 Financial information 16 Board of directors, Public Radio Fund advisory council and staff 17 Mission 2 *Based on Arbitron and Radio Research Consortium 2008 and 2009 data From the board chairman The measure of any nonprofit is the difference it makes for clients, communities and the larger purpose it serves for society. -

The New Frontier: an Integrated Framework for Equity & Transformative Improvement in Education

The New Frontier: An Integrated Framework for Equity & Transformative Improvement in Education By Sheryl Petty, California Tomorrow October 2010 About California Tomorrow Since 1984, California Tomorrow has specialized in the development of strategies to bring about equity and inclusion. We have worked with schools, districts, community colleges, after school programs, community building organizations, and philanthropy to provide vision for just and inclusive communities and build the capacity of institutions to effectively serve all students, with emphasis on those marginalized and underserved. We have worked at local, state and national levels using research, advocacy, and technical assistance. We focus on ensuring that students have rigorous academic preparation from culturally responsive practitioners grounded in their communities, to develop skills of compassion and understanding for themselves and others, to become critically conscious citizens able to reflect on the strengths and structural inequities in society and work collectively to create a more just world. Thank you to our individual donors and the California Endowment for making this publication possible. Staff Sheryl Petty, Executive Director Singhashri (Kica) Gazmuri Luiz Guevara Board of Directors Susan Sandler Anna Basallaje Sheri Dunn Berry Michael Howe Craig McGarvey Hugo Morales California Tomorrow 360 22nd St., Suite 640 Oakland, CA 94612 (510) 496-0220 (510) 496-0225 fax [email protected] www.californiatomorrow.org to ToC © 2010, California Tomorrow Design -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

FOOTBALL IS DEAD! LONG LIVE FOOTBALL! ARGENTINE FOOTBALL LITERATURE BETWEEN TRADITION AND RESISTANCE By CARLOS ANDRES BERTOGLIO A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 © 2016 Carlos Andrés Bertoglio To myself, for all the hard work. To the universe, for being there. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS All my gratitude goes to my family for supporting me through the duration of this project. Only they know how hard it was. To every one of my professors at UF for guiding me in spite of my own stubbornness. To Dr. Gillian Lord for all your experience and kindness. To Martín, my dissertation chair, for teaching me more than he can begin to imagine. To my parents and brothers, who were always with me, despite being thousands of miles away. To my dad, for creating light out of the darkness and giving me the gift of reading. To my mom, for teaching me about the unbreakable power of dreams. To my dear aunt Mecha for introducing me to literature at a very young age. To Argentina’s free public education system without which I would not be who I am. To Antonio Sajid, Carlos Ayerdi Castillo, Whitman Suarez, Diana Pedraza, Andrea Villa, Iván Yerkovich, Eliana Guise, Mariela Ferreyra and the rest of the few but valuable friends who make our lives much better. Finally, to Yanina for her immense love and perseverance and little Giovanni for making me realize I still have so much to learn.