WHAT IS a BIRD SPECIES? J. T. Leverich, Cambridge in the April

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TREND NOTE Number 021, October 2012

SCOTTISH NATURAL HERITAGE TREND NOTE Number 021, October 2012 SEABIRDS IN SCOTLAND Prepared by Simon Foster and Sue Marrs of SNH Knowledge Information Management Unit using results from the Seabird Monitoring Programme and the Joint Nature Conservation Committee Scotland has internationally important populations of several seabirds. Their conservation is assisted through a network of designated sites. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the 50 Special Protection Areas (SPA) which have seabirds listed as a feature of interest. The map shows the widespread nature of the sites and the predominance of important seabird areas on the Northern Isles (Orkney and Shetland), where some of our largest seabird colonies are present. The most recent estimate of seabird populations was obtained from Birds of Scotland (Forrester et al., 2007). Table 1 shows the population levels for all seabirds regularly breeding in Scotland. Table 1: Population Estimates for Breeding Seabirds in Scotland. Figure 1: Special Protection Areas for Seabirds Breeding in Scotland. Species* Unit** Estimate Key Points Northern fulmar 486,000 AOS Manx shearwater 126,545 AOS Trends are described for 11 of the 24 European storm-petrel 31,570+ AOS species of seabirds breeding in Leach’s storm-petrel 48,057 AOS Scotland Northern gannet 182,511 AOS Great cormorant c. 3,600 AON Nine have shown sustained declines European shag 21,500-30,000 PAIRS over the past 20 years. Two have Arctic skua 2,100 AOT remained stable. Great skua 9,650 AOT The reasons for the declines are Black headed -

Copulation and Mate Guarding in the Northern Fulmar

COPULATION AND MATE GUARDING IN THE NORTHERN FULMAR SCOTT A. HATCH Museumof VertebrateZoology, University of California,Berkeley, California 94720 USA and AlaskaFish and WildlifeResearch Center, U.S. Fish and WildlifeService, 1011 East Tudor Road, Anchorage,Alaska 99503 USA• ABSTRACT.--Istudied the timing and frequency of copulation in mated pairs and the occurrenceof extra-paircopulation (EPC) among Northern Fulmars (Fulmarus glacialis) for 2 yr. Copulationpeaked 24 days before laying, a few daysbefore females departed on a prelaying exodus of about 3 weeks. I estimated that females were inseminated at least 34 times each season.A total of 44 EPC attemptswas seen,9 (20%)of which apparentlyresulted in insem- ination.Five successful EPCs were solicitated by femalesvisiting neighboring males. Multiple copulationsduring a singlemounting were rare within pairsbut occurredin nearly half of the successfulEPCs. Both sexesvisited neighborsduring the prelayingperiod, and males employed a specialbehavioral display to gain acceptanceby unattended females.Males investedtime in nest-siteattendance during the prelaying period to guard their matesand pursueEPC. However, the occurrenceof EPC in fulmars waslargely a matter of female choice. Received29 September1986, accepted 16 February1987. THEoccurrence and significanceof extra-pair Bjorkland and Westman 1983; Buitron 1983; copulation (EPC) in monogamousbirds has Birkhead et al. 1985). generated much interest and discussion(Glad- I attemptedto documentthe occurrenceand stone 1979; Oring 1982; Ford 1983; McKinney behavioral contextof extra-pair copulationand et al. 1983, 1984). Becausethe males of monog- mate guarding in a colonial seabird,the North- amous species typically make a large invest- ern Fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis). Fulmars are ment in the careof eggsand young, the costof among the longest-lived birds known, and fi- being cuckolded is high, as are the benefits to delity to the same mate and nest site between the successfulcuckolder. -

Tube-Nosed Seabirds) Unique Characteristics

PELAGIC SEABIRDS OF THE CALIFORNIA CURRENT SYSTEM & CORDELL BANK NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY Written by Carol A. Keiper August, 2008 Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary protects an area of 529 square miles in one of the most productive offshore regions in North America. The sanctuary is located approximately 43 nautical miles northwest of the Golden Gate Bridge, and San Francisco California. The prominent feature of the Sanctuary is a submerged granite bank 4.5 miles wide and 9.5 miles long, which lay submerged 115 feet below the ocean’s surface. This unique undersea topography, in combination with the nutrient-rich ocean conditions created by the physical process of upwelling, produces a lush feeding ground. for countless invertebrates, fishes (over 180 species), marine mammals (over 25 species), and seabirds (over 60 species). The undersea oasis of the Cordell Bank and surrounding waters teems with life and provides food for hundreds of thousands of seabirds that travel from the Farallon Islands and the Point Reyes peninsula or have migrated thousands of miles from Alaska, Hawaii, Australia, New Zealand, and South America. Cordell Bank is also known as the albatross capital of the Northern Hemisphere because numerous species visit these waters. The US National Marine Sanctuaries are administered and managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) who work with the public and other partners to balance human use and enjoyment with long-term conservation. There are four major orders of seabirds: 1) Sphenisciformes – penguins 2) *Procellariformes – albatross, fulmars, shearwaters, petrels 3) Pelecaniformes – pelicans, boobies, cormorants, frigate birds 4) *Charadriiformes - Gulls, Terns, & Alcids *Orders presented in this seminar In general, seabirds have life histories characterized by low productivity, delayed maturity, and relatively high adult survival. -

The Birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an Annotated Checklist

European Journal of Taxonomy 306: 1–69 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2017.306 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2017 · Gedeon K. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A32EAE51-9051-458A-81DD-8EA921901CDC The birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an annotated checklist Kai GEDEON 1,*, Chemere ZEWDIE 2 & Till TÖPFER 3 1 Saxon Ornithologists’ Society, P.O. Box 1129, 09331 Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Germany. 2 Oromia Forest and Wildlife Enterprise, P.O. Box 1075, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia. 3 Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, Centre for Taxonomy and Evolutionary Research, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 3 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F46B3F50-41E2-4629-9951-778F69A5BBA2 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F59FEDB3-627A-4D52-A6CB-4F26846C0FC5 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:A87BE9B4-8FC6-4E11-8DB4-BDBB3CFBBEAA Abstract. Oromia is the largest National Regional State of Ethiopia. Here we present the first comprehensive checklist of its birds. A total of 804 bird species has been recorded, 601 of them confirmed (443) or assumed (158) to be breeding birds. At least 561 are all-year residents (and 31 more potentially so), at least 73 are Afrotropical migrants and visitors (and 44 more potentially so), and 184 are Palaearctic migrants and visitors (and eight more potentially so). Three species are endemic to Oromia, 18 to Ethiopia and 43 to the Horn of Africa. 170 Oromia bird species are biome restricted: 57 to the Afrotropical Highlands biome, 95 to the Somali-Masai biome, and 18 to the Sudan-Guinea Savanna biome. -

Geographic Variation in Leach's Storm-Petrel

GEOGRAPHIC VARIATION IN LEACH'S STORM-PETREL DAVID G. AINLEY Point Reyes Bird Observatory, 4990 State Route 1, Stinson Beach, California 94970 USA ABSTRACT.-•A total of 678 specimens of Leach's Storm-Petrels (Oceanodroma leucorhoa) from known nestinglocalities was examined, and 514 were measured. Rump color, classifiedon a scale of 1-11 by comparison with a seriesof reference specimens,varied geographicallybut was found to be a poor character on which to base taxonomic definitions. Significant differences in five size charactersindicated that the presentlyaccepted, but rather confusing,taxonomy should be altered: (1) O. l. beali, O. l. willetti, and O. l. chapmani should be merged into O. l. leucorhoa;(2) O. l. socorroensisshould refer only to the summer breeding population on Guadalupe Island; and (3) the winter breeding Guadalupe population should be recognizedas a "new" subspecies,based on physiological,morphological, and vocal characters,with the proposedname O. l. cheimomnestes. The clinal and continuoussize variation in this speciesis related to oceanographicclimate, length of migration, mobility during the nesting season,and distancesbetween nesting islands. Why oceanitidsfrequenting nearshore waters during nestingare darker rumped than thoseoffshore remains an unanswered question, as does the more basic question of why rump color varies geographicallyin this species.Received 15 November 1979, accepted5 July 1980. DURING field studies of Leach's Storm-Petrels (Oceanodroma leucorhoa) nesting on Southeast Farallon Island, California in 1972 and 1973 (see Ainley et al. 1974, Ainley et al. 1976), several birds were captured that had dark or almost completely dark rumps. The subspecificidentity of the Farallon population, which at that time was O. -

Update on the Birds of Isla Guadalupe, Baja California

UPDATE ON THE BIRDS OF ISLA GUADALUPE, BAJA CALIFORNIA LORENZO QUINTANA-BARRIOS and GORGONIO RUIZ-CAMPOS, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Apartado Postal 1653, Ense- nada, Baja California, 22800, México (U. S. mailing address: PMB 064, P. O. Box 189003, Coronado, California 92178-9003; [email protected] PHILIP UNITT, San Diego Natural History Museum, P. O. Box 121390, San Diego, California 92112-1390; [email protected] RICHARD A. ERICKSON, LSA Associates, 20 Executive Park, Suite 200, Irvine, California 92614; [email protected] ABSTRACT: We report 56 bird specimens of 31 species taken on Isla Guadalupe, Baja California, between 1986 and 2004 and housed at the Colección Ornitológica del Laboratorio de Vertebrados de la Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Ensenada, along with other sight and specimen records. The speci- mens include the first published Guadalupe records for 10 species: the Ring-necked Duck (Aythya collaris), Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus), Bonaparte’s Gull (Larus philadelphia), Ash-throated Flycatcher (Myiarchus cinerascens), Warbling Vireo (Vireo gilvus), Tree Swallow (Tachycineta bicolor), Yellow Warbler (Dendroica petechia), Magnolia Warbler (Dendroica magnolia), Yellow-headed Blackbird (Xan- thocephalus xanthocephalus), and Orchard Oriole (Icterus spurius). A specimen of the eastern subspecies of Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater ater) and a sight record of the Gray-cheeked Thrush (Catharus minimus) are the first reported from the Baja California Peninsula (and islands). A photographed Franklin’s Gull (Larus pipixcan) is also an island first. Currently 136 native species and three species intro- duced in North America have been recorded from the island and nearby waters. -

SEAPOP Studies in the Lofoten and Barents Sea Area in 2006

249 SEAPOP studies in the Lofoten and Barents Sea area in 2006 Tycho Anker-Nilssen Robert T. Barrett Jan Ove Bustnes Kjell Einar Erikstad Per Fauchald Svein-Håkon Lorentsen Harald Steen Hallvard Strøm Geir Helge Systad Torkild Tveraa NINA Publications NINA Report (NINA Rapport) This is a new, electronic series beginning in 2005, which replaces the earlier series NINA commissioned reports and NINA project reports. This will be NINA’s usual form of reporting completed research, monitoring or review work to clients. In addition, the series will include much of the institute’s other reporting, for example from seminars and conferences, results of internal research and review work and literature studies, etc. NINA report may also be issued in a second language where appropriate. NINA Special Report (NINA Temahefte) As the name suggests, special reports deal with special subjects. Special reports are produced as required and the series ranges widely: from systematic identification keys to information on important problem areas in society. NINA special reports are usually given a popular scientific form with more weight on illustrations than a NINA report. NINA Factsheet (NINA Fakta) Factsheets have as their goal to make NINA’s research results quickly and easily accessible to the general public. The are sent to the press, civil society organisations, nature management at all levels, politicians, and other special interests. Fact sheets give a short presentation of some of our most important research themes. Other publishing In addition to reporting in NINA’s own series, the institute’s employees publish a large proportion of their scientific results in international journals, popular science books and magazines. -

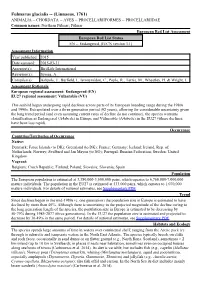

Fulmarus Glacialis

Fulmarus glacialis -- (Linnaeus, 1761) ANIMALIA -- CHORDATA -- AVES -- PROCELLARIIFORMES -- PROCELLARIIDAE Common names: Northern Fulmar; Fulmar European Red List Assessment European Red List Status EN -- Endangered, (IUCN version 3.1) Assessment Information Year published: 2015 Date assessed: 2015-03-31 Assessor(s): BirdLife International Reviewer(s): Symes, A. Compiler(s): Ashpole, J., Burfield, I., Ieronymidou, C., Pople, R., Tarzia, M., Wheatley, H. & Wright, L. Assessment Rationale European regional assessment: Endangered (EN) EU27 regional assessment: Vulnerable (VU) This seabird began undergoing rapid declines across parts of its European breeding range during the 1980s and 1990s. Extrapolated over a three generation period (92 years), allowing for considerable uncertainty given the long trend period (and even assuming current rates of decline do not continue), the species warrants classification as Endangered (A4abcde) in Europe and Vulnerable (A4abcde) in the EU27 (where declines have been less rapid). Occurrence Countries/Territories of Occurrence Native: Denmark; Faroe Islands (to DK); Greenland (to DK); France; Germany; Iceland; Ireland, Rep. of; Netherlands; Norway; Svalbard and Jan Mayen (to NO); Portugal; Russian Federation; Sweden; United Kingdom Vagrant: Belgium; Czech Republic; Finland; Poland; Slovakia; Slovenia; Spain Population The European population is estimated at 3,380,000-3,500,000 pairs, which equates to 6,760,000-7,000,000 mature individuals. The population in the EU27 is estimated at 533,000 pairs, which equates to 1,070,000 mature individuals. For details of national estimates, see Supplementary PDF. Trend Since declines began in the mid-1980s (c. one generation) the population size in Europe is estimated to have declined by more than 40%. -

Terrestrial Birds and Conservation Priorities in Baja California Peninsula1

Terrestrial Birds and Conservation Priorities in Baja California Peninsula1 Ricardo Rodríguez-Estrella2 ________________________________________ Abstract The Baja California peninsula has been categorized as as the Nautical Ladder that will have impacts at the an Endemic Bird Area of the world and it is an im- regional level on the biodiversity. Proposals for portant wintering area for a number of aquatic, wading research and conservation action priorities are given for and migratory landbird species. It is an important area the conservation of birds and their habitats throughout for conservation of bird diversity in northwestern the Peninsula of Baja California. México. In spite of this importance, only few, scattered studies have been done on the ecology and biology of bird species, and almost no studies exist for priority relevant species such as endemics, threatened and other key species. The diversity of habitats and climates Introduction permits the great resident landbird species richness throughout the Peninsula, and also explains the pre- The Baja California peninsula is an important area for sence of an important number of landbird migrant conservation of bird diversity in northwestern México species. Approximately 140 resident and 65 migrant (CCA 1999, Arizmendi and Marquez 2000). It has landbird species have been recorded for Baja California been classified as an Endemic Bird Area of the world state (BCN) and 120 resident and 55 landbird migrant (Stattersfield et al. 1998) and also has been considered species for Baja California Sur state (BCS). Three ter- as an important wintering area for a number of aquatic, restrial endemics have been recognized for BCN and wading and migratory landbird species (Massey and four endemics for BCS. -

The Collection of Birds from São Tomé and Príncipe at the Instituto De Investigação Científica Tropical of the University of Lisbon (Portugal)

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 600:The 155–167 collection (2016) of birds from São Tomé and Príncipe at the Instituto de Investigação... 155 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.600.7899 DATA PAPER http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research The collection of birds from São Tomé and Príncipe at the Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical of the University of Lisbon (Portugal) Miguel Monteiro1,2, Luís Reino1,2,3, Martim Melo1,4, Pedro Beja1,2, Cristiane Bastos-Silveira5, Manuela Ramos7, Diana Rodrigues5, Isabel Queirós Neves5,6, Susana Consciência8, Rui Figueira1,2 1 CIBIO/InBIO-Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Vairão, Portugal 2 CEABN/InBio, Centro de Ecologia Aplicada “Professor Baeta Neves”, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa, Tapada da Ajuda, 1349-017 Lisboa, Portugal 3 CIBIO/InBIO-Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade de Évora, 7004-516 Évora, Portugal 4 Percy FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701X, South Africas 5 Museu Nacional de História Natural e da Ciência, Universidade de Lisboa, Rua da Escola Politécnica 56, 1250-102 Lisboa, Portugal 6 CESAM-Centre for Environmental and Marine Studies, Universidade de Aveiro, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal 7 MARE-FCUL, DOP/UAç - Departamento Oceanografia e Pescas, Univ. Açores, Rua Prof. Dr. Fre- derico Machado, 9901-862 Horta, Portugal 8 Estrada de Mem Martins n251 1ºDto, 2725-391 Mem Martins, Sintra, Portugal Corresponding author: Rui Figueira ([email protected]) Academic editor: G. Sangster | Received 29 January 2015 | Accepted 2 June 2016 | Published 22 June 2016 http://zoobank.org/68209E54-00D0-4EFA-B095-AB7D346ACD8E Citation: Monteiro M, Reino L, Melo M, Beja P, Bastos-Silveira C, Ramos M, Rodrigues D, Neves IQ, Consciência S, Figueira R (2016) The collection of birds from São Tomé and Príncipe at the Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical of the University of Lisbon (Portugal). -

WB-V40(4)-Webcomp.Pdf

Volume 40, Number 4, 2009 Recent Purple Martin Declines in the Sacramento Region of California: Recovery Implications Daniel A. Airola and Dan Kopp ............254 Further Decline in Nest-Box Use by Vaux’s Swifts in Northeastern Oregon Evelyn L. Bull and Charles T. Collins ........................260 Use of a Nesting Platform by Gull-billed Terns and Black Skimmers at the Salton Sea, California Kathy C. Molina, Mark A. Ricca, A. Keith Miles, and Christian Schoneman ...............................267 Birds of Prey and the Band-tailed Pigeon on Isla Guadalupe, Mexico Juan-Pablo Gallo-Reynoso and Ana-Luisa Figueroa-Carranza ..................................................278 Food Habits of Wild Turkeys in National Forests of Northern California and Central Oregon Greta M. Wengert, Mourad W. Gabriel, Ryan L. Mathis, and Thomas Hughes ......................................284 Seasonal Variation in the Diet of the Barn Owl in Northwestern Nevada Abigail C. Myers, Christopher B. Goguen, and Daniel C. Rabbers ............................................................292 NOTES First Record of a Mangrove Yellow Warbler for Arizona Nathan K. Banfield and Patricia J. Newell ...............................297 Prey Remains in Nests of Four Corners Golden Eagles, 1998– 2008 Dale W. Stahlecker, David G. Mikesic, James N. White, Spin Shaffer, John P. DeLong, Mark R. Blakemore, and Craig E. Blakemore ................................................................301 Book Reviews Dave Trochlell and John Sterling .........................307 Featured -

Appendix D5 Restore Seabirds to Baja California Pacific Islands

Appendix D5 Restore Seabirds to Baja California Pacific Islands Appendix D5 Restore Seabirds to Baja California Pacific Islands Appendix D5 Restore Seabirds on the Baja California Pacific Islands The Natural Resource Trustees for the Montrose case (Trustees) have evaluated a variety of seabird restoration actions for the Baja California Pacific islands in Mexico. These islands support a wide range of seabirds that nest in or use the Southern California Bight (SCB). Restoration efforts would target a suite of seabird species, including the Cassin’s auklet, Brandt’s cormorant, double-crested cormorant, California brown pelican, ashy storm-petrel, and Xantus’s murrelet. To streamline the evaluation of these actions, the general background and regulatory framework is provided below. Detailed project descriptions are then provided for the following islands: (1) Guadalupe Island, (2) Coronado and Todos Santos Islands, (3) San Jeronimo and San Martín Islands, and (4) San Benito, Natividad, Asunción, and San Roque Islands. The actions discussed in this appendix do not cover all of the potential seabird restoration actions for the Baja California Pacific islands; therefore, the Trustees will consider additional actions in the future for implementation under this Restoration Plan, as appropriate. D5.1 GENERAL BACKGROUND The Baja California Pacific islands are located in the northwestern portion of Mexico, off of the Pacific coast of Baja California (Figure D5-1). Of the 12 islands or island groups (18 total islands) in this region, nine present unique opportunities for seabird restoration. Three of these islands or island groups (Coronado, Todos Santos, and San Martín) are oceanographically considered part of the SCB.