Algar, D. A., A. A. Burbidge, and G. J. Angus., 2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palaeoecology and Sea Level Changes: Decline of Mammal Species Richness During Late Quaternary Island Formation in the Montebello Islands, North-Western Australia

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org Palaeoecology and sea level changes: Decline of mammal species richness during late Quaternary island formation in the Montebello Islands, north-western Australia Cassia J. Piper and Peter M. Veth ABSTRACT Changes in sea level and the formation of islands impact the distributions and abundances of local flora and fauna, with palaeo-environmental investigations provid- ing a context for biological conservation. The palaeo-environmental knowledge of the north-west of Australia during the late Quaternary is sparse, particularly the impact of island formation on local faunas. In 1991 and 1993 Peter Veth and colleagues conducted archaeological surveys of the Montebello Islands, an archipelago situated 70 – 90 km from the present-day coastline of north-west Australia. A group of three caves were found during this survey on the eastern side of Campbell Island. Two of the caves, Noala and Hayne’s Caves, were analysed by Veth and colleagues in the early 1990s; the last cave, Morgan’s Cave, remained unanalysed because it contained negligible archaeological material. It provides an opportunity to refine the interpretation of palaeo-environmental conditions, further information on the original pre-European fauna of the north-west shelf, the for- mation of the islands due to sea level rise, and the impact of sea level rise on local fau- nas. The fossil fauna assemblage of Morgan’s Cave was sorted, identified to the low- est taxonomic level possible, and counted for analysis on relative abundance for paleo- environmental interpretation. There are marked patterns of species loss and changing relative abundances in certain species, consistent with island formation due to sea level rise. -

THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT, MARINE HABITATS, and CHARACTERISTICS... Download 846.8 KB

Records of the Western Australian Museum Supplement No. 59: 9-13 (2000). THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT, MARINE HABITATS, AND CHARACTERISTICS OF THE MARINE FAUNA F.E. Wells and P.F. Berry Western Australian Museum, Francis Street, Perth, Western Australia 6000, Australia The Physical Environment In broad morphological terms, the Montebello The geography, physiography, climate and Islands and associated reefs resemble the shape of oceanography of the region have been summarised an arrowhead, comprising a central "chain" of by Deegan (1992). These are discussed below in islands with unusually irregular or convolu.ted relation to how they affect habitats and fauna. coastlines lying on a north-south axis. These islands The sea surface temperature range of 20-33°C are in close proximity to one another and are places the Montebellos within Ekman's (1976) separated by narrow channels, which generally run tropical zone, delineated from the subtropical zone east-west. The northernmost island in this chain by the 20°C minimum isotherm. In terms of (Northwest Island) forms the apex and from it an biogeographical provinces, determined principally almost unbroken barrier reef runs to the south-west by water temperature, the Montebellos fall within and a large elongate island (Trimouille Island) and the Dampierian or Northern Australian Tropical series of smaller islands runs to the south-east Province (Wilson and AlIen, 1987). (Figure 1). The quantity and quality of suspended particulate matter is an important environmental parameter for marine organisms. The waters of the Montebellos Marine Habitats are little influenced by terrigenous sediments from The geomorphology provides an unusually high the mainland or the islands themselves because diversity of habitat types, including protected there is insignificant freshwater runoff in the area. -

Habitat Conservation Plan a Plan for the Protection of the Perdido Key

Perdido Key Programmatic Habitat Conservation Plan Escambia County, Florida HABITAT CONSERVATION PLAN A PLAN FOR THE PROTECTION OF THE PERDIDO KEY BEACH MOUSE, SEA TURTLES, AND PIPING PLOVERS ON PERDIDO KEY, FLORIDA Prepared in Support of Incidental Take Permit No. for Incidental Take Related to Private Development and Escambia County Owned Land and Infrastructure Improvements on Perdido Key, Florida Prepared for: ESCAMBIA COUNTY BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS P.O. BOX 1591 PENSACOLA, FL 32591 Prepared by: PBS&J 2401 EXECUTIVE PLAZA, SUITE 2 PENSACOLA, FLORIDA 32504 Submitted to: U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE ECOLOGICAL SERVICES & FISHERIES RESOURCES OFFICE 1601 BALBOA AVENUE PANAMA CITY, FLORIDA 32450 Final Draft January 2010 Draft Submitted December 2008 Draft Revised March 2009 Draft Revised May 2009 Draft Revised October 2009 ii Perdido Key Programmatic Habitat Conservation Plan Escambia County, Florida TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................ viii LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................ x LIST OF APPENDICES ................................................................................................. xi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................ xii 1.0 INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background -

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island Operated by Chevron Australia This document has been printed by a Sustainable Green Printer on stock that is certified carbon in joint venture with neutral and is Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) mix certified, ensuring fibres are sourced from certified and well managed forests. The stock 55% recycled (30% pre consumer, 25% post- Cert no. L2/0011.2010 consumer) and has an ISO 14001 Environmental Certification. ISBN 978-0-9871120-1-9 Gorgon Project Osaka Gas | Tokyo Gas | Chubu Electric Power Chevron’s Policy on Working in Sensitive Areas Protecting the safety and health of people and the environment is a Chevron core value. About the Authors Therefore, we: • Strive to design our facilities and conduct our operations to avoid adverse impacts to human health and to operate in an environmentally sound, reliable and Dr Dorian Moro efficient manner. • Conduct our operations responsibly in all areas, including environments with sensitive Dorian Moro works for Chevron Australia as the Terrestrial Ecologist biological characteristics. in the Australasia Strategic Business Unit. His Bachelor of Science Chevron strives to avoid or reduce significant risks and impacts our projects and (Hons) studies at La Trobe University (Victoria), focused on small operations may pose to sensitive species, habitats and ecosystems. This means that we: mammal communities in coastal areas of Victoria. His PhD (University • Integrate biodiversity into our business decision-making and management through our of Western Australia) -

Remotely Monitoring Change in Vegetation Cover on the Montebello Islands, Western Australia, in Response to Introduced Rodent Eradication

RESEARCH ARTICLE Remotely Monitoring Change in Vegetation Cover on the Montebello Islands, Western Australia, in Response to Introduced Rodent Eradication Cheryl Lohr1*, Ricky Van Dongen2, Bart Huntley2, Lesley Gibson3, Keith Morris1 1. Department of Parks and Wildlife, Science and Conservation Division, Woodvale, Western Australia, Australia, 2. Department of Parks and Wildlife, GIS Section, Kensington, Western Australia, Australia, 3. Department of Parks and Wildlife, Science and Conservation Division, Keiran McNamara Conservation Science Centre, 17 Dick Perry Drive, Technology Park, Kensington, WA 6151, Australia *[email protected] OPEN ACCESS Citation: Lohr C, Van Dongen R, Huntley B, Gibson L, Morris K (2014) Remotely Monitoring Abstract Change in Vegetation Cover on the Montebello Islands, Western Australia, in Response to The Montebello archipelago consists of 218 islands; 80 km from the north-west Introduced Rodent Eradication. PLoS ONE 9(12): e114095. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0114095 coast of Western Australia. Before 1912 the islands had a diverse terrestrial fauna. Editor: Benjamin Lee Allen, University of By 1952 several species were locally extinct. Between 1996 and 2011 rodents and Queensland, Australia cats were eradicated, and 5 mammal and 2 bird species were translocated to the Received: September 16, 2014 islands. Monitoring of the broader terrestrial ecosystem over time has been limited. Accepted: October 29, 2014 We used 20 dry-season Landsat images from 1988 to 2013 and estimation of green Published: December 1, 2014 fraction cover in nadir photographs taken at 27 sites within the Montebello islands Copyright: ß 2014 Lohr et al. This is an open- and six sites on Thevenard Island to assess change in vegetation density over time. -

Assessment of Species Listing Proposals for CITES Cop18

VKM Report 2019: 11 Assessment of species listing proposals for CITES CoP18 Scientific opinion of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food and Environment Utkast_dato Scientific opinion of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food and Environment (VKM) 15.03.2019 ISBN: 978-82-8259-327-4 ISSN: 2535-4019 Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food and Environment (VKM) Po 4404 Nydalen N – 0403 Oslo Norway Phone: +47 21 62 28 00 Email: [email protected] vkm.no vkm.no/english Cover photo: Public domain Suggested citation: VKM, Eli. K Rueness, Maria G. Asmyhr, Hugo de Boer, Katrine Eldegard, Anders Endrestøl, Claudia Junge, Paolo Momigliano, Inger E. Måren, Martin Whiting (2019) Assessment of Species listing proposals for CITES CoP18. Opinion of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food and Environment, ISBN:978-82-8259-327-4, Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food and Environment (VKM), Oslo, Norway. VKM Report 2019: 11 Utkast_dato Assessment of species listing proposals for CITES CoP18 Note that this report was finalised and submitted to the Norwegian Environment Agency on March 15, 2019. Any new data or information published after this date has not been included in the species assessments. Authors of the opinion VKM has appointed a project group consisting of four members of the VKM Panel on Alien Organisms and Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), five external experts, and one project leader from the VKM secretariat to answer the request from the Norwegian Environment Agengy. Members of the project group that contributed to the drafting of the opinion (in alphabetical order after chair of the project group): Eli K. -

Factors That Contribute to the Establishment of Marine Protected Areas in Western Australia

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2014 Factors that contribute to the establishment of marine protected areas in Western Australia Andrew Hill University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Hill, A. (2014). Factors that contribute to the establishment of marine protected areas in Western Australia (Doctor of Natural Resource Management). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/92 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Factors that Contribute to the Establishment of Marine Protected Areas in Western Australia Andrew Hill School of Arts and Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Australia Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Natural Resource Management May 2014 DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any University or other institute of tertiary education. Information derived from published and unpublished work of others has been acknowledged in the text with references provided for that material. -

Translocation Assessment

MALA RECOVERY PLAN TRIMOUILLE and NORTH WEST ISLAND - Montebello Group WA Translocation Assessment .,. 'Tryal Rock HONTE BELLO ISLANDS ,:· South West Reefs North East South West ~ Rocnard I Scewart f 1 0 Sholl I ~ q HanH \. b Pucoe Island T o Poivre Reel . -~ cRound I Barrow Island L , Shoals ) \, ... 9[South Pup I ,,.. Puns• I ~I .t.i Sand uy i,'Bncl• I 1,4~~1 Li1hdooc Re..f..,_ Miry Ann• R•e ( M· i:~7con w.,.,~._;..;, and c-·•• 1•,11 _I? \, Prepared by Don Langford Parks and Wildlife Commission of the Northern Territory for the Mala Recovery Team October 1997 i~{£dt}I ... f/ I ....~ ~ ~ G p.:;::: ~: . I 1· .. ~.- , , CiVi~let Island . I • "'-_. , > :: : i I I I Whale Rae i . i ld-tsland-~-""---<,.,._'r'iF,!,1-a-g..,.ls""'"l-a n-d+- _----+-- o ; i !. I I . .. The· I Montebello· j . Islands· , . ""' .- a Prohibited ~rea under ti • . Act 1952. Persons wishin obtain· the permissi_o Western Austiralia Are · I Introduction The Mala Recovery Team endorsed a proposal to visit Trimouille and North West Islands in the Montebello Group, W.A. to determine the suitability of the islands for translocation of the critically endangered Rufous Hare-wallaby (central Australian sub species) Lagorchestes hirsutus unnamed subsp. (Mala Recovery Team - [Minutes], Broome, 15 May, 1997. Item 4). A visit was made to the islands by D. Langford of the Parks and Wildlife Commission of the Northern Territory (PWCNT) Alice Springs, at the invitation of the Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM) during the week 14th - 18th July, 1997. -

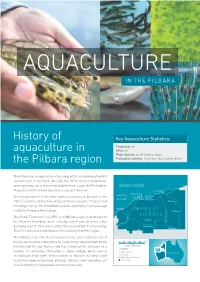

Aquaculture I N T H E P I L B a R A

AQUACULTURE I N T H E P I L B A R A History of Key Aquaculture Statistics: Production: nil aquaculture in Value: nil Major Species: pearl oysters, algae the Pilbara region Production systems: long-lines, algal pond culture The Pilbara has a long history of pearling with Cossack being the first pearling port in the North West. By the 1870s more than 80 boats were operating out of the port and divers from Japan, the Philippines, INDIAN OCEAN Malaysia and China were regularly stopping in the town. Port Hedland Dampier Archipelago Montebello Islands Cossack The establishment of the pearl farming industry in Broome in the Dampier Barrow Island Karratha Roebourne 1950's led to the establishment of pearl farms along the Pilbara coast Marble Bar including Onslow, the Montebello Islands and Flying Foam passage Onslow Pannawonica inside the Dampier Archipelago. W E S T Nullagine The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008 had a significant impact on P I L B A R A Tom Price the Western Australian pearl industry, which saw its gross value declining from $175 million in 2002/03 to around $60.7 million today. Paraburdoo Newman The GFC led to a total withdrawal of the industry from the region. The Pilbara's high rate of solar incidence has seen it listed as one of the top six locations in the world for solar energy development by the 0 50 100 150 200 250 International Energy Agency and has attracted the attention of a Scale in Kilometres LEGEND number of companies interested in algae culture. -

Montebello/Barrow Islands Marine Conservation Reserves 2007–2017 Management Plan No 55

Management Plan for the Montebello/Barrow Islands Marine Conservation Reserves 2007–2017 Management Plan No 55 MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE MONTEBELLO/BARROW ISLANDS MARINE CONSERVATION RESERVES 2007-2017 Management Plan No. 55 including the Montebello Islands Marine Park, Barrow Island Marine Park and Barrow Island Marine Management Area. VISION To conserve the marine flora and fauna, habitats and water quality of the Montebello/Barrow islands area. The area will support commercial and recreational activities which are compatible with the maintenance of environmental quality and be valued as an important ecological, economic and social asset by the community. Prepared by the Department of Environment and Conservation Cover photographs courtesy of Col Roberts/Lochman Transparencies (insert 1), Peter & Margy Nicholas/Lochman Transparencies (insert 2), and Department of Environment and Conservation (insert 3). Department of Environment and Conservation ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Advisory Committee for the Proposed Montebello/Barrow Islands Marine Conservation Reserve committed considerable time and effort in discussions and meetings that provided the basis of this management plan. The advisory committee greatly assisted the Marine Parks and Reserves Authority (MPRA) and the former Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM) in developing the proposal and their efforts are acknowledged. Members of the committee were Norm Halse (Chair), John Baas, John Jenkin, Russell Lagdon, Guy Leyland, Vicki Long, Noel Parkin, Kelly Pendoley, Iva Stejskal and Craig Thomas. Many groups and individuals provided valuable input to the advisory committee, the Department of Environment and Conservation (DEC) and the MPRA through Sector Reference Groups, individual submissions and out-of- session discussions. In particular, representatives from the hydrocarbon companies, pearling industry, charter boat industry, Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association Ltd., Pearl Producers Association and Recfishwest provided valuable information and constructive input. -

Gazette 21572

[75] VOL. CCCXXVI OVER THE COUNTER SALES $2.75 INCLUDING G.S.T. TASMANIAN GOV ERNMENT • U • B E AS RT LIT AS•ET•FIDE TASMANIA GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY WEDNESDAY 20 JANUARY 2016 No. 21 572 ISSN 0039-9795 CONTENTS Notices to Creditors Notice Page JOHN DAVID RUSSELL late of 2111 Elphinstone Road North Hobart in Tasmania orchard farm manager/divorced died on Administration and Probate ..................................... 76 the fourteenth day of September 2015: Creditorsnext of kin and others having claims in ·respect of the property of the Councils ................................................................... 107 abovenamed deceased are required by the Executors Helen Elizabeth Gill and Sally Ann Giacon c/- Tremayne Fay and Crown Lands ............................................................ 78 Rheinberger 3 Heathfield Ave Hobart in Tasmania to send particulars of their claim in writing to the Registrar of the Living Marine Resources Management ................... 77 Supreme Court of Tasmania by Monday the twenty-second day of February 2016 after which date the Executors may distribute Mental Health ........................................................... 75 the assets having regard only to the claims of which they then· have notice. Nature Conservation ................................................ 77, 81 Dated this twentieth day of January 2016. Notices to Creditors ................................................. 75 TREMAYNE FAY AND RHEINBERGER, Solicitors for the Estate. Public Health ........................................................... -

1165 Mardie Salt Project Desktop Review.Docx

Environmental desktop review and reconnaissance site visit for the Mardie Salt Project Prepared for BC Iron Ltd September 2017 Final Report Environmental desktop review and reconnaissance site visit for the Mardie Salt Project Prepared for BC Iron Ltd Environmental desktop review and reconnaissance site visit for the Mardie Salt Project Prepared for BC Iron Ltd Final Report Authors: Ryan Ellis, Jarrad Clark, Volker Framenau, Grant Wells Reviewer: Jarrad Clark Date: 29 September 2017 Submitted to: Les Purves, Michael Klvac ©Phoenix Environmental Sciences Pty Ltd 2017 The use of this report is solely for the Client for the purpose in which it was prepared. Phoenix Environmental Sciences accepts no responsibility for use beyond this purpose. All rights are reserved and no part of this report may be reproduced or copied in any form without the written permission of Phoenix Environmental Sciences or the Client. Phoenix Environmental Sciences Pty Ltd 1/511 Wanneroo Rd BALCATTA WA 6021 P: 08 9345 1608 F: 08 6313 0680 E: [email protected] Project code: 1165-MSP-BCI-ECO i Environmental desktop review and reconnaissance site visit for the Mardie Salt Project Prepared for BC Iron Ltd EXECUTIVE SUMMARY BC Iron Ltd (BCI) is investigating the feasibility of developing the Mardie Salt Project (the MSP), a sodium chloride (NaCl) salt production project owned 100% by BCI on tenements between Dampier and Onslow in the north-west of Western Australia. The Project aims to develop a nominal 3–3.5 Mtpa high purity industrial grade sodium chloride salt from seawater via a solar evaporation, crystallization and raw salt purification operation.