Whose Neighbourhood? 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tall Buildings: up up and Away?

expect the best Tall Buildings: Up Up and Away? by Marc Kemerer Originally published in Blaneys on Building (April 2011) There has been much debate about tall buildings (buildings over 12 storeys in height) in Toronto in the past number of years particularly due to the decreasing availability of development land, and the province and municipal forces on intensification – but how tall is too tall and where should tall buildings be permitted? Marc Kemerer is a municipal As we have reported previously, the City of Toronto continues to review proposals for tall towers partner at Blaney McMurtry , against its Tall Buildings Guidelines which set out standards for podiums, setbacks between sister with significant experience in towers and the like. Some of those Guidelines were incorporated into the City’s new comprehensive all aspects of municipal planning and development. zoning by-law (under appeal and subject to possible repeal by City Council - see the Planning Updates section of this issue) while the Guidelines themselves were renewed last year by City Marc may be reached directly Council for continued use in design review. at 416.593.2975 or [email protected]. Over the last couple of years the City has embarked on the “second phase” of its tall buildings review through the “Tall Buildings Downtown Project”. In connection with this phase, the City has recently released the study commissioned by the City on this topic entitled: “Tall Buildings: Inviting Change in Downtown Toronto” (the “Study”). The Study focused on three issues: where should tall buildings be located; how high should tall buildings be; and how should tall buildings behave in their context. -

Schedule 4 Description of Views

SCHEDULE 4 DESCRIPTION OF VIEWS This schedule describes the views identified on maps 7a and 7b of the Official Plan. Views described are subject to the policies set out in section 3.1.1. Described views marked with [H] are views of heritage properties and are specifically subject to the view protection policies of section 3.1.5 of the Official Plan. A. PROMINENT AND HERITAGE BUILDINGS, STRUCTURES & LANDSCAPES A1. Queens Park Legislature [H] This view has been described in a comprehensive study and is the subject of a site and area specific policy of the Official Plan. It is not described in this schedule. A2. Old City Hall [H] The view of Old City hall includes the main entrance, tower and cenotaph as viewed from the southwest and southeast corners at Temperance Street and includes the silhouette of the roofline and clock tower. This view will also be the subject of a comprehensive study. A3. Toronto City Hall [H] The view of City Hall includes the east and west towers, the council chamber and podium of City Hall and the silhouette of those features as viewed from the north side of Queen Street West along the edge of the eastern half of Nathan Phillips Square. This view will be the subject of a comprehensive study. A4. Knox College Spire [H] The view of the Knox College Spire, as it extends above the roofline of the third floor, can be viewed from the north along Spadina Avenue at the southeast corner of Bloor Street West and at Sussex Avenue. A5. -

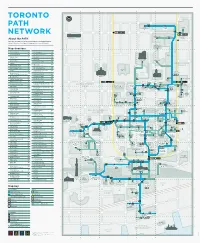

PATH Network

A B C D E F G Ryerson TORONTO University 1 1 PATH Toronto Atrium 10 Dundas Coach Terminal on Bay East DUNDAS ST W St Patrick DUNDAS ST W NETWORK Dundas Ted Rogers School One Dundas Art Gallery of Ontario of Management West Yonge-Dundas About the PATH Square 2 2 Welcome to the PATH — Toronto’s Downtown Underground Pedestrian Walkway UNIVERSITY AVE linking 30 kilometres of underground shopping, services and entertainment ST PATRICK ST BEVERLEY ST BEVERLEY ST M M c c CAUL ST CAUL ST Toronto Marriott Downtown Eaton VICTORIA ST Centre YONGE ST BAY ST Map directory BAY ST A 11 Adelaide West F6 One King West G7 130 Adelaide West D5 One Queen Street East G4 Eaton Tower Adelaide Place C5 One York D11 150 York St P PwC Tower D10 3 Toronto 3 Atrium on Bay F1 City Hall 483 Bay Street Q 2 Queen Street East G4 B 222 Bay E7 R RBC Centre B8 DOWNTOWN Bay Adelaide Centre F5 155 Wellington St W YONGE Bay Wellington Tower F8 RBC WaterPark Place E11 Osgoode UNIVERSITY AVE 483 Bay Richmond-Adelaide Centre D5 UNIVERSITY AVE Hall F3 BAY ST 120 Adelaide St W BAY ST CF Toronto Bremner Tower / C10 Nathan Eaton Centre Southcore Financial Centre (SFC) 85 Richmond West E5 Phillips Canada Life Square Brookfield Place F8 111 Richmond West D5 Building 4 Old City Hall 4 2 Queen Street East C Cadillac Fairview Tower F4 Roy Thomson Hall B7 Cadillac Fairview Royal Bank Building F6 Tower CBC Broadcast Centre A8 QUEEN ST W Osgoode QUEEN ST W Thomson Queen Building Simpson Tower CF Toronto Eaton Centre F4 Royal Bank Plaza North Tower E8 QUEEN STREET One Queen 200 Bay St Four -

Board of Directors Meeting

Board of Directors Meeting Agenda and Meeting Book THURSDAY, DECEMBER 5, 2019 FROM 08:30 AM TO 11:30 AM WATERFRONT TORONTO 20 BAY STREET, SUITE 1310 TORONTO, ON, M5J 2N8 Meeting Book - Board of Directors Meeting Agenda 8:30 a.m. 1. Motion to Approve Meeting Agenda Approval S. Diamond 8:35 a.m. 2. Declaration of Conflicts of Interest Declaration All 8:40 a.m. 3. Chair’s Opening Remarks Information S. Diamond 8:50 a.m. 4. Consent Agenda a) Draft Minutes of Open Session of the October 10 and 24, 2019 Board Approval All Meeting - Page 4 b) Draft Minutes of Open Session of the October 31, 2019 Board Approval All Meeting - Page 11 c) CEO Report - Page 15 Information G. Zegarac d) Finance Audit and Risk Management (FARM) Committee Chair's Information K. Sullivan Open Session Report - Page 44 e) Human Resources, Governance and Stakeholder Relations (HRGSR) Information S. Palvetzian Committee Chair's Open Session Report - Page 47 f) Investment, Real Estate and Quayside (IREQ) Committe Chair's Open Information M. Mortazavi Session Report - Page 48 9:00 a.m. 5. Port Lands Flood Protection (60% Design Stage Gate Status Approval D. Kusturin Update) Cover Sheet - Page 49 Presentation is attached as Appendix A to the Board Book 9:15 a.m. 6. Waterfront Toronto Priority Projects - Construction Update Information D. Kusturin Cover sheet - Page 50 Presentation is attached as Appendix B to the Board Book 9:30 a.m. 7. Motion to go into Closed Session Approval All Closed Session Agenda The Board will discuss items 8, 9 (a), (b), (c), (d) & (e) , 10, 11 and -

The Politicization of the Scarborough Rapid Transit Line in Post-Suburban Toronto

THE ‘TOONERVILLE TROLLEY’: THE POLITICIZATION OF THE SCARBOROUGH RAPID TRANSIT LINE IN POST-SUBURBAN TORONTO Peter Voltsinis 1 “The world is watching.”1 A spokesperson for the Province of Ontario’s (the Province) Urban Transportation Development Corporation (UTDC) uttered those poignant words on March 21, 1985, one day before the Toronto Transit Commission’s (TTC) inaugural opening of the Scarborough Rapid Transit (SRT) line.2 One day later, Ontario Deputy Premier Robert Welch gave the signal to the TTC dispatchers to send the line’s first trains into the Scarborough Town Centre Station, proclaiming that it was “a great day for Scarborough and a great day for public transit.”3 For him, the SRT was proof that Ontario can challenge the world.4 This research essay outlines the development of the SRT to carve out an accurate place for the infrastructure project in Toronto’s planning history. I focus on the SRT’s development chronology, from the moment of the Spadina Expressway’s cancellation in 1971 to the opening of the line in 1985. Correctly classifying what the SRT represents in Toronto’s planning history requires a clear vision of how the project emerged. To create that image, I first situate my research within Toronto’s dominant historiographical planning narratives. I then synthesize the processes and phenomena, specifically postmodern planning and post-suburbanization, that generated public transit alternatives to expressway development in Toronto in the 1970s. Building on my synthesis, I present how the SRT fits into that context and analyze the changing landscape of Toronto land-use politics in the 1970s and early-1980s. -

TORONTO PORT AUTHORITY (Doing Business As Portstoronto) MANAGEMENT's DISCUSSION & ANALYSIS – 2017 (In Thousands of Dolla

TORONTO PORT AUTHORITY (Doing Business as PortsToronto) MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION & ANALYSIS – 2017 (In thousands of dollars) May 3, 2018 Management's discussion and analysis (MD&A) is intended to assist in the understanding and assessment of the trends and significant changes in the results of operations and financial condition of the Toronto Port Authority, doing business as PortsToronto (the “Port Authority” or “TPA”) for the years ended December 31, 2017 and 2016 and should be read in conjunction with the 2017 Audited Financial Statements (the “Financial Statements”) and accompanying notes. Summary The Port Authority continued to be profitable in 2017. Net Income (excluding the gain on the sale of the 30 Bay Street/60 Harbour Street Property) for the year was $6,368, slightly down from $6,684 in 2016. This MD&A will discuss the reasons for changes in Net Income year over year, as well as highlight other areas impacting the Port Authority’s financial performance in 2017. The Port Authority presents its financial statements under International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”). The accounting policies set out in Note 2 of the Financial Statements have been applied in preparing the Financial Statements for the year ended December 31, 2017, and in the comparative information presented in these Financial Statements for the year ended December 31, 2016. Introduction The TPA was continued on June 8, 1999 as a government business enterprise under the Canada Marine Act as the successor to the Toronto Harbour Commissioners. The Port Authority is responsible for operating the lands and harbour it administers in the service of local, regional and national social and economic objectives, and for providing infrastructure and services to marine and air transport to facilitate these objectives. -

James T. Lemon Fonds

University of Toronto Archives and Records Management Services James T. Lemon Fonds Prepared by: Marnee Gamble Nov. 1995 Revised Nov. 2005 Revised Nov 2016 © University of Toronto Archives and Records Management Services 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE…………………………………………………………………………1 SCOPE AND CONTENT………………………………………………………………………...2 Series 1 Biographical……………………………………………………………………….3 Series 2 Correspondence…………………………………………………………………...3 Series 3 Conferences and speaking engagements…………………………………………...4 Series 4 Publishing Activities………………………………………………………………4 Series 5 Reviews…………………………………………………………………………...5 Series 6 Research Grants…………………………………………………………………..5 Series 7 Teaching Files……………………………………………………………………..5 Series 8 Student Files………………………………………………………………………6 Series 9 References………………………………………………………………………...6 Series 10 Department of Geography………………………………………………………..7 Series 11 University of Toronto…………………………………………………………….7 Series 12 Professional Associations and Community Groups………………………………8 Series 13 New Democratic Party…………………………………………………………...8 Series 14 Christian Youth Groups………………………………………………………….8 Series 15 Family Papers…………………………………………………………………….9 Appendix 1 Series 12: Professional Associations and Community Groups 10 Appendix 2 Series 7 : Teaching student essays B1984-0027, B1986-0015, B1988-0054 12 University of Toronto Archives James T. Lemon Fonds BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE: Raised in West Lorne, Ontario, James (Jim) Thomas Lemon attended the University of Western Ontario where he received his Bachelor of Arts in Geography (1955). He later attended the University of Wisconsin where he received a Master of Science in Geography (1961) as well as his Ph.D. (1964). In 1967, after having worked as an Assistant Professor at the University of California, Prof. Lemon joined the University of Toronto Geography Department, where he remained until his retirement in 1994. His career has been spent in the field of urban historical geography of which he has written numerous articles, papers and chapters in books. -

390 Bay Street

Ground Floor & PATH Retail for Lease 390 Bay Street Eric Berard Sales Representative 647.528.0461 [email protected] RETAIL FOR LEASE 390 BAY ST 390 Bay Street CITY HALL OLD CITY EATON - CENTRE N.P. SQUARE HALL Queen St FOUR SEASONS CENTRE FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS University Ave Richmond St Wine Academy Bay St Bay York St York Yonge St Yonge Sheppard St Sheppard Church St Church Adelaide St FIRST CANADIAN PLACE SCOTIA PLAZA King St TORONTO DOMINION CENTRE COMMERCE COURT WALRUS PUB Wellington St ROYAL BANK BROOKFIELD PLAZA PLACE View facing south from Old City Hall OVERVIEW DEMOGRAPHICS (3KM, 2020) 390 Bay St. (Munich RE Centre) is located at northwest corner 702,631 of Bay St. and Richmond St. W within Toronto’s Financial Core. DAYTIME POPULATION It is a BOMA BEST Gold certified 378,984 sf A-Class office tower, with PATH connected retail. 390 Bay is well located with connec- $ $114,002 tivity to The Sheraton Centre, Hudson’s Bay Company/Saks Fifth AVG. HOUSEHOLD INCOME Avenue, Toronto Eaton Centre and direct proximity to Nathan Phillips Square and Toronto City Hall. Full renovations have been 182,265 completed to update the Lobby and PATH level retail concourse. HOUSEHOLDS RETAIL FOR LEASE 390 Bay Street "Client" Tenant Usable Area Major Vertical Penetration Floor Common Area Building Common Area UP DN UP DN Version: Prepared: 30/08/2016 UP FP2A Measured: 01/05/2019 390 Bay Street Toronto, Ontario 100 Floor 1 FHC ELEV GROUND FLOOR AVAILABILITY DN ELEC. UP ROOM ELEV ELEV DN Please Refer to Corresponding ELEV MECH. -

Portstoronto to Sell Head-Office Property at 30 Bay Street to Oxford Properties and CPPIB

PortsToronto to Sell Head-Office Property at 30 Bay Street to Oxford Properties and CPPIB Historic Toronto Harbour Commission building to be restored and maintained in any future development planned for property Proceeds of sale paid to PortsToronto will be directed towards paying down debt and making infrastructure investments Toronto (May 1, 2017) – PortsToronto today announced that it has sold its property at the corner of 30 Bay and 60 Harbour Streets to Oxford Properties Group (Oxford) and Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB), who will each own a 50 per cent stake. The historic Toronto Harbour Commission building, which currently serves as headquarters for PortsToronto and is located on the site along with a surface parking lot, will be restored and maintained as part of any future development plan. The sale closed today and the transaction is valued at $96 million, a portion of which will be payable over the next three years. The proceeds from this sale will be used to support PortsToronto’s federal mandate to manage operations on a self-sustaining basis in order to reinvest funds into marine safety, environmental protection, community programming, and transportation infrastructure. The federal Minister of Transport has granted an amendment to PortsToronto’s Letters Patent to enable the sale to close. “The South Core is a burgeoning area for business and residential development in Toronto given its optimal location, public transit access and amenities,” said Robert Poirier, Chair of the Board, PortsToronto. “We are pleased that this sale will provide for future opportunities that will improve utilization of the property which is consistent with PortsToronto’s federal mandate and governing Letters Patent. -

GTHA Investment Report February 2019

GTHA Investment Report February 2019 FOR MORE INFORMATION, PLEASE CONTACT: Ryan McAskile Vice President, Broker | Private Capital Investment Group Direct: 416 791 7237 Mobile: 416 725 2703 [email protected] Accelerating Success. Welcome to the February edition of the GTHA Investment Report, the most Top 10 Transactions for February 2019 comprehensive overview of GTHA investment sales activity in the market. Asset Type Property Municipality Region Price Unit Price / Unit Office Dynamic Funds Tower Toronto Toronto $473,000,000 Square Feet $728 Total transaction volume for the month of February was Office 56 Wellesley Street West Toronto Toronto $98,000,000 Square Feet $454 approximately $1.63 billion across all asset classes. Toronto saw Res Land 77 River Street & Labatt Avenue Toronto Toronto $54,400,000 Acres $40,597,015 the most activity at $1.04 billion followed by York at $214 million. Res Land 7082 Islington Avenue Vaughan York $35,000,000 Acres $1,105,042 Office sales had the highest transaction volume amongst asset classes at $640 million followed by residential land and ICI land at Apartment 15 Walmer Road Toronto Toronto $30,000,000 Units $384,615 $336 million and $251 million, respectively. The largest transaction Industrial 185 William Smith Drive Whitby Durham $27,500,000 Square Feet $135 for the month of February was the office sale of the Dynamic Office Warden City Centre Markham York $26,520,000 Square Feet $208 Funds Tower at 1 Adelaide St E for $473 million. Retail 4916 - 4946 Dundas Street West Etobicoke Toronto $26,500,000 Square Feet $602 This month we feature THE HUB, Oxford Properties and CPPIB’s Res Land 250 Lawrence Avenue West & 219 Glengarry Avenue Toronto Toronto $26,000,000 Acres $18,181,818 proposed 1.4 million-square- foot, 60-storey office tower at 30 Industrial 2301 - 2311 Royal Windsor Drive Mississauga Peel $25,750,000 Square Feet $126 Bay Street. -

181 Bay Street, Toronto Office for Sub-Sublease

181 BAY STREET, TORONTO OFFICE FOR SUB-SUBLEASE PREMIER SHORT TERM SHARED SPACE SUB-SUBLEASE OPPORTUNITY AT A LANDMARK TORONTO ADDRESS FOR MORE INFORMATION PLEASE CONTACT ASHLAR URBAN REALTY INC. Real Estate Brokerage 166 Pearl Street, Suite 300 Toronto, ON Canada M5H 1L3 T 416 205 9222 F 416 205 9228 W ashlarurban.com TORONTO’S URBAN COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE EXPERTS CLARKE STRUTHERS* JOEL GOULDING Vice President Sales Representative 416 205 9222 ext 254 416 205 9222 ext 251 [email protected] [email protected] Disclaimer: Although the information contained within is from sources believed to be reliable, no warranty or representation is made as to its accuracy being subject to errors, omissions, conditions, prior lease, withdrawal or other changes without notice and same should not be relied upon without independent verification. Ashlar Urban Realty Inc. *Sales Representative 181 BAY STREET PROPERTY SUMMARY 181 Bay Street, also known as Brookfield Place, is an office complex in downtown Toronto that is considered one of North America’s truly great people places. It consists of two towers, Bay Wellington Tower and TD Canada Trust Tower, which are linked by the six-storey Allen Lambert Galleria. Located in the heart of the financial district, it houses the world’s most prestigious financial, commercial, and legal firms, as well as the Hockey Hall of Fame. Brookfield Place is a green building that has been awarded a Gold level of certification in the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED®) Existing Buildings: Operations and Maintenance program. Being connected to the underground PATH pedestrian walkway system, major hotels, retail and entertainment centres are just footsteps away. -

2017 Annual Report

Annual Report 2017 Investing Today for Tomorrow AVAILABLE IN THESE FORMATS PRINT WEBSITE MOBILE © Toronto Port Authority 2018. All rights reserved. To obtain additional copies of this report please contact: 60 Harbour Street, Toronto, ON M5J 1B7 Canada PortsToronto The Toronto Port Authority, doing business as Communications and Public Affairs Department PortsToronto since January 2015, is a government 60 Harbour Street business enterprise operating pursuant to the Toronto, Ontario, M5J 1B7 Canada Marine Act and Letters Patent issued by Canada the federal Minister of Transport. The Toronto Port Phone: 416 863 2075 Authority is hereafter referred to as PortsToronto. E-mail: [email protected] 2 PortsToronto | Annual Report 2017 Table of Contents About PortsToronto 4 Mission and Vision 5 Message from the Chair 6 Message from the Chief Executive Officer 8 Corporate Governance 12 Business Overview Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport 14 Port of Toronto 18 Outer Harbour Marina 22 Real Estate and Property Holdings 24 Four Pillars 26 City Building 27 Community Engagement 30 Environmental Stewardship 40 Financial Sustainability 44 Statement of Revenue and Expenses 45 Celebrating 225 years of port activity 46 About PortsToronto The Toronto Port Authority, doing business as and hereinafter referred to as PortsToronto, is a federal government business enterprise that owns and operates Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport, Marine Terminal 52 within the Port of Toronto, the Outer Harbour Marina and various properties along Toronto’s waterfront. Responsible for the safety and efficiency of marine navigation in the Toronto Harbour, PortsToronto also exercises regulatory control and public works services for the area, works with partner organizations to keep the Toronto Harbour clean, issues permits to recreational boaters and co-manages the Leslie Street Spit site with partner agency the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority on behalf of the provincial Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry.