4. Bolobedu Pline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

African Herp News

African Herp News Newsletter of the Herpetological Association of Africa Number 55 DECEMBER 2011 HERPETOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF AFRICA http://www. wits.ac.za/haa FOUNDED 1965 The HAA is dedicated to the study and conservation of African reptiles and amphibians. Membership is open to anyone with an interest in the African herpetofauna. Members receive the Association’s journal, African Journal of Herpetology (which publishes review papers, research articles, and short communications – subject to peer review) and African Herp News , the Newsletter (which includes short communications, natural history notes, geographical distribution notes, herpetological survey reports, venom and snakebite notes, book reviews, bibliographies, husbandry hints, announcements and news items). NEWSLETTER EDITOR ’S NOTE Articles shall be considered for publication provided that they are original and have not been published elsewhere. Articles will be submitted for peer review at the Editor’s discretion. Authors are requested to submit manuscripts by e-mail in MS Word ‘.doc’ or ‘.docx’ format. COPYRIGHT: Articles published in the Newsletter are copyright of the Herpetological Association of Africa and may not be reproduced without permission of the Editor. The views and opinions expressed in articles are not necessarily those of the Editor . COMMITTEE OF THE HERPETOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF AFRICA CHAIRMAN Aaron Bauer, Department of Biology, Villanova University, 800 Lancaster Avenue, Villanova, Pennsylvania 19085, USA. [email protected] SECRETARY Jeanne Tarrant, African Amphibian Conservation Research Group, NWU. 40A Hilltop Road, Hillcrest 3610, South Africa. [email protected] TREASURER Abeda Dawood, National Zoological Gardens, Corner of Boom and Paul Kruger Streets, Pretoria 0002, South Africa. [email protected] JOURNAL EDITOR John Measey, Applied Biodiversity Research, Kirstenbosch Research Centre, South African Biodiversity Institute, P/Bag X7, Claremont 7735, South Africa. -

At Ōrokonui Ecosanctuary

Ontogenetic differences in behaviour of the Otago skink (Oligosoma otagense) at Ōrokonui Ecosanctuary Holly Thompson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, Zoology University of Otago Dunedin, New Zealand January 2021 i Abstract Personalities of animals may demonstrate ontogenetic changes in response to a plethora of different environmental factors and experiences early in life. Understanding these ontogenetic personality changes aids in understanding how individuals tolerate, act and react to environments, conspecifics and other species throughout their lifespan. This behavioural topic remains relatively unexplored for many reptilian species. Because non-avian reptiles are such a diverse group of vertebrates in, ecology, behaviour and morphology, more research on ontogenetic personality changes is required for this class of animals. Relatively little is known about the social behaviour and personalities of the Otago skink (Oligosoma otagense), or how they differ between age-groups. This study aimed to examine (1) whether Otago skinks demonstrated repeatability of behaviours over four sample periods, and therefore have personalities, (2) whether sociality, aggression, boldness and exploration levels differed between adult, sub-adult and juvenile Otago skinks, and (3) whether temporal variation of sociality, aggression, boldness and exploration variables differed between adult, sub-adult and juvenile Otago skinks over four sample periods. This study was conducted on the translocated -

Olympus AH Eco Assessment

Reg No. 2005/122/329/23 VAT Reg No. 4150274472 PO Box 751779 Gardenview 2047 Tel: 011 616 7893 Fax: 086 724 3132 Email: [email protected] www.sasenvironmental.co.za BIODIVERSITY ASSESSMENT AS PART OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL AUTHORISATION AND WATER USE LICENCING PROCESS FOR THE FAIRVIEW TAILINGS DAM AND HISTORIC DUMP RECLAMATION PROJECT NEAR BARBERTON, MPUMALANGA PROVINCE Prepared for Cabanga Environmental November 2019 Part C: Faunal Assessment Prepared by: Scientific Terrestrial Services Report author: D. van der Merwe Report reviewer: C. Hooton S. van Staden (Pri Sci. Nat) Report Reference: STS 190055 Date: November 2019 STS 190055 – Part C: Faunal Assessment November 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.1. Background .................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Assumptions and Limitations ........................................................................................ 2 2.1 General approach ......................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Sensitivity Mapping ...................................................................................................... 4 3.1 Faunal Habitat .............................................................................................................. 4 3.2 Mammals.................................................................................................................... 10 3.3 Avifauna .................................................................................................................... -

Guides Level Ii Manual 2005 December

GUIDING LEVEL II A TRAINING MANUAL DESIGNED TO ASSIST WITH PREPARATION FOR THE FGASA LEVEL II AND TRAILS GUIDE EXAMS All rights reserved. No part of the material may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by an information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of Lee Gutteridge. (INCLUDING MORE THAN FOUR HUNDRED PHOTOS AND DIAGRAMS) COMPILED BY LEE GUTTERIDGE THIS STUDY MATERIAL CONFORMS TO THE SYLLABUS SET BY FGASA FOR THE LEVEL II EXAMS AND IS APPROVED BY PROFESSOR W.VAN HOVEN OF THE CENTRE FOR WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT AT THE UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA P.O. Box 441, Mookgopong, 0560, Limpopo, South Africa. Cell 083 667 7586 2 LEVEL TWO TRAINING MANUAL This manual has been compiled from the perspective of a guide in the field. In writing it I asked myself what can I use on a game drive, or game walk as regards information. These aspects covered in this manual will give the guide good, interesting and factual information for direct discussion with the guest. No one book will cover every aspect so here I have included sections on the following topics. 1. Ecology 2. Mammals 3. Birds 4. Reptiles and Amphibians 5. Astronomy 6. Botany 7. Insects, Arachnids and their relatives 8. Geology and Climatology 9. Fish 10. Survival 11. AWH and VPDA The problem for guides is not always finding the answers, but also what is the question to be researched in the first place? It is difficult for a guide to pre-empt what guests will ask them over their guiding careers, but many of the questions and answers which will come into play have been covered here. -

African Herp News

African Herp News Newsletter of the Herpetological Association of Africa Number 55 DECEMBER 2011 Articles HEWITT , J. 1925. On some new species of Reptiles and Amphibians from South Africa. Records of the Albany Museum 3(4): 343–369 + Plates XV–XIX. MEASEY , G.J. (ed). 2011. Ensuring a future for South Africa’s frogs: a strategy for con- servation research. SANBI Biodiversity Series 19. South African National Biodiver- sity Institute, Pretoria. MINTER , L. R., B URGER , M., H ARRISON , J. A., B RAACK , H. H., B ISHOP , P .J. & KLOEPFER , D. (eds). 2004. Atlas and Red Data Book of the Frogs of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. SI/MAB Series #9. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, 360 pp. SOUTH AFRICAN FROG RE-ASSESSMENT GROUP (SA-FR OG) & I UCN SSC AMPHIBIAN SPECIALIST GROUP , 2010. Vandijkophrynus amatolicus . In: IUCN 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2. www.iucnredlist.org (accessed 29 November 2011). SOUTH AFRICAN WEATHER SERVICE www.weathersa.co.za/web/Content.asp? contentID=88 (accessed 25 September 2011). ***** REPTILE SURVEY OF VENETIA LIMPOPO NATURE RESERVE, LIMPOPO PROVINCE - SOUTH AFRICA WERNER CONRADIE 1, HANLIE ENGELBRECHT 2, ANTHONY HERREL 3, G. JOHN MEASEY 4, STUART V. NIELSEN 5, BIEKE VANHOOYDONCK 6 AND KRYSTAL A. TOLLEY 2,4 1 Port Elizabeth Museum, Port Elizabeth, South Africa 2Department of Botany and Zoology, University of Stellenbosch, Matieland 7602, South Africa 3UMR 7179 C.N.R.S/M.N.H.N., Département d'Ecologie et de Gestion de la Biodiversité, 57 rue Cuvier, Case postale 55, 75231, Paris Cedex 5, France 4Applied Biodiversity Research Division, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Private Bag X7, Claremont, Cape Town, 7735 South Africa 5Dept. -

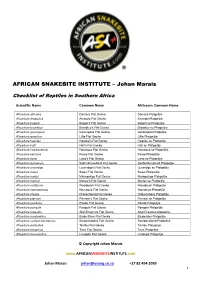

Johan Marais

AFRICAN SNAKEBITE INSTITUTE – Johan Marais Checklist of Reptiles in Southern Africa Scientific Name Common Name Afrikaans Common Name Afroedura africana Damara Flat Gecko Damara Platgeitjie Afroedura amatolica Amatola Flat Gecko Amatola Platgeitjie Afroedura bogerti Bogert's Flat Gecko Bogert se Platgeitjie Afroedura broadleyi Broadley’s Flat Gecko Broadley se Platgeitjie Afroedura gorongosa Gorongosa Flat Gecko Gorongosa Platgeitjie Afroedura granitica Lillie Flat Gecko Lillie Platgeitjie Afroedura haackei Haacke's Flat Gecko Haacke se Platgeitjie Afroedura halli Hall's Flat Gecko Hall se Platgeitjie Afroedura hawequensis Hawequa Flat Gecko Hawequa se Platgeitjie Afroedura karroica Karoo Flat Gecko Karoo Platgeitjie Afroedura langi Lang's Flat Gecko Lang se Platgeitjie Afroedura leoloensis Sekhukhuneland Flat Gecko Sekhukhuneland Platgeitjie Afroedura loveridgei Loveridge's Flat Gecko Loveridge se Platgeitjie Afroedura major Swazi Flat Gecko Swazi Platgeitjie Afroedura maripi Mariepskop Flat Gecko Mariepskop Platgeitjie Afroedura marleyi Marley's Flat Gecko Marley se Platgeitjie Afroedura multiporis Woodbush Flat Gecko Woodbush Platgeijtie Afroedura namaquensis Namaqua Flat Gecko Namakwa Platgeitjie Afroedura nivaria Drakensberg Flat Gecko Drakensberg Platgeitjie Afroedura pienaari Pienaar’s Flat Gecko Pienaar se Platgeitjie Afroedura pondolia Pondo Flat Gecko Pondo Platgeitjie Afroedura pongola Pongola Flat Gecko Pongola Platgeitjie Afroedura rupestris Abel Erasmus Flat Gecko Abel Erasmus platgeitjie Afroedura rondavelica Blyde River -

African Herp News

African Herp News Newsletter of the Herpetological Association of Africa Number 55 DECEMBER 2011 HERPETOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF AFRICA http://www. wits.ac.za/haa FOUNDED 1965 The HAA is dedicated to the study and conservation of African reptiles and amphibians. Membership is open to anyone with an interest in the African herpetofauna. Members receive the Association’s journal, African Journal of Herpetology (which publishes review papers, research articles, and short communications – subject to peer review) and African Herp News , the Newsletter (which includes short communications, natural history notes, geographical distribution notes, herpetological survey reports, venom and snakebite notes, book reviews, bibliographies, husbandry hints, announcements and news items). NEWSLETTER EDITOR ’S NOTE Articles shall be considered for publication provided that they are original and have not been published elsewhere. Articles will be submitted for peer review at the Editor’s discretion. Authors are requested to submit manuscripts by e-mail in MS Word ‘.doc’ or ‘.docx’ format. COPYRIGHT: Articles published in the Newsletter are copyright of the Herpetological Association of Africa and may not be reproduced without permission of the Editor. The views and opinions expressed in articles are not necessarily those of the Editor . COMMITTEE OF THE HERPETOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF AFRICA CHAIRMAN Aaron Bauer, Department of Biology, Villanova University, 800 Lancaster Avenue, Villanova, Pennsylvania 19085, USA. [email protected] SECRETARY Jeanne Tarrant, African Amphibian Conservation Research Group, NWU. 40A Hilltop Road, Hillcrest 3610, South Africa. [email protected] TREASURER Abeda Dawood, National Zoological Gardens, Corner of Boom and Paul Kruger Streets, Pretoria 0002, South Africa. [email protected] JOURNAL EDITOR John Measey, Applied Biodiversity Research, Kirstenbosch Research Centre, South African Biodiversity Institute, P/Bag X7, Claremont 7735, South Africa. -

The Distribution and Abundance of Herpetofauna on a Quaternary Aeolian Dune Deposit: Implications for Strip Mining

The distribution and abundance of herpetofauna on a Quaternary aeolian dune deposit: Implications for Strip Mining Bryan Maritz A dissertation submitted to the School of Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Science. Johannesburg, South Africa July, 2007 ABSTRACT Exxaro KZN Sands is planning the development of a heavy minerals strip mine south of Mtunzini, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. The degree to which mining activities will affect local herpetofauna is poorly understood and baseline herpetofaunal diversity data are sparse. This study uses several methods to better understand the distribution and abundance of herpetofauna in the area. I reviewed the literature for the grid squares 2831DC and 2831 DD and surveyed for herpetofauna at the study site using several methods. I estimate that 41 amphibian and 51 reptile species occur in these grid squares. Of these species, 19 amphibian and 39 reptile species were confirmed for the study area. In all, 29 new unique, grid square records were collected. The paucity of ecological data for cryptic fauna such as herpetofauna is particularly evident for taxa that are difficult to sample. Because fossorial herpetofauna spend most of their time below the ground surface, their ecology and biology are poorly understood and warrant further investigation. I sampled fossorial herpetofauna using two excavation techniques. Sites were selected randomly from the study area which was expected to host high fossorial herpetofaunal diversity and abundance. A total of 218.6 m3 of soil from 311 m2 (approximately 360 metric tons) was excavated and screened for herpetofauna. -

Captive Wildlife Regulations, 2021, W-13.12 Reg 5

1 CAPTIVE WILDLIFE, 2021 W-13.12 REG 5 The Captive Wildlife Regulations, 2021 being Chapter W-13.12 Reg 5 (effective June 1, 2021). NOTE: This consolidation is not official. Amendments have been incorporated for convenience of reference and the original statutes and regulations should be consulted for all purposes of interpretation and application of the law. In order to preserve the integrity of the original statutes and regulations, errors that may have appeared are reproduced in this consolidation. 2 W-13.12 REG 5 CAPTIVE WILDLIFE, 2021 Table of Contents PART 1 PART 5 Preliminary Matters Zoo Licences and Travelling Zoo Licences 1 Title 38 Definition for Part 2 Definitions and interpretation 39 CAZA standards 3 Application 40 Requirements – zoo licence or travelling zoo licence PART 2 41 Breeding and release Designations, Prohibitions and Licences PART 6 4 Captive wildlife – designations Wildlife Rehabilitation Licences 5 Prohibition – holding unlisted species in captivity 42 Definitions for Part 6 Prohibition – holding restricted species in captivity 43 Standards for wildlife rehabilitation 7 Captive wildlife licences 44 No property acquired in wildlife held for 8 Licence not required rehabilitation 9 Application for captive wildlife licence 45 Requirements – wildlife rehabilitation licence 10 Renewal 46 Restrictions – wildlife not to be rehabilitated 11 Issuance or renewal of licence on terms and conditions 47 Wildlife rehabilitation practices 12 Licence or renewal term PART 7 Scientific Research Licences 13 Amendment, suspension, -

Captive Wildlife Allowed List

Saskatchewan Captive Wildlife Allowed Species List (as of June 1, 2021) AMPHIBIANS (CLASS AMPHIBIA) Class (Common Name) Scientific Name Family Ambystomatidae Axolotl Ambystoma mexicanum Marble Salamander Ambystoma opacum Family Bombinatoridae Oriental Fire-Bellied Toad Bombina orientalis Family Bufonidae Green Toad Anaxyrus debilis Black Indonesian Toad Bufo asper Indonesian Toad Duttaphrynus melanostictus Family Ceratophryidae Surinam Horned Frog Ceratophrys cornuta Chacoan Horned Frog Ceratophrys cranwelli Argentine Horned Frog Ceratophrys ornata Budgett’s Frog Lepidobatrachus laevis Family Dendrobatidae Dart Poison Frog Dendrobates auratus Yellow-banded Poison Dart Frog Dendrobates leucomelas Dyeing Dart Frog Dendrobates tinctorius Yellow-striped Poison Frog Dendrobates truncatus Family Hylidae Clown Tree Frog Dendropsophus leucophyllatus Bird Poop Tree Frog Dendropsophus marmoratus Barking Tree Frog Dryophytes gratiosus Squirrel Tree Frog Dryophytes squirellus Green Tree Frog Dryophytes cinereus Cuban Tree Frog Osteopilus septentrionalis Haitian Giant Tree Frog Osteopilus vastus White’s Tree Frog Ranoidea caerulea Brazilian Black and White Milky Frog Trachycephalus resinifictrix Hyperoliidae African Reed Frog Hyperolius concolor Family Mantellidae Baron’s Mantella Mantella baroni Brown Mantella Mantella betsileo Family Megophryidae Long-nosed Horned Frog Megophrys nasuta Family Microhylidae Tomato Frog Dyscophus guineti Chubby Frog Kaloula pulchra Banded Rubber Frog Phrynomantis bifasciatus Emerald Hopper Frog Scaphiophryne madagascariensis -

South Africa Mega II Trip Report 8Th October to 1St November 2016

South Africa Mega II Trip Report 8th October to 1st November 2016 Drakensberg Rockjumper by Adam Riley Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Andre Bernon RBT South Africa – Mega II Trip Report 2016 2 Top 10 birds seen on the trip (as voted by the participants) 1. Drakensberg Rockjumper 2. Blue Crane 3. Botha’s Lark 4. Cape Rockjumper 5. African Penguin 6. Eastern Bronze-naped Pigeon 7. Pink-throated Twinspot 8. Cape Sugarbird 9. Blue Swallow 10. Spotted Eagle-Owl Tour Summary The southern African sub-region has one of the highest number of endemic and near-endemic bird species on the continent. This, coupled with great infrastructure, makes South Africa a highly rewarding country to explore. Our first day was set to be an arrival day where everyone was met by their Rockjumper tour leader at our accommodation in South Africa’s largest city - Johannesburg. This did not stop us from ticking off a few bird species; these came in the form of Karoo Thrush, Crested Barbet, Cape Robin-Chat, Red- headed Finch, Cape Wagtail, Southern Masked Weaver and Southern Red Bishop. After an introductory chat during our first dinner together, talking about the day planned ahead, we made our way to bed in preparation for an early start the following morning. We managed to leave before sunrise and arrived at our first birding destination north of Pretoria, in the Rust de Winter area, when the temperature was still cool and the sky a bit overcast. This aided us in our birding success as we managed to get great views of some target species reaching their easternmost distribution here.