Elephant Atlas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Index September 1976-August 1977 Vol. 3

INDEX I- !/oluJne3 Numbers 1-12 ONANTIQUES , September, 1976-August, 1977 AND COLLECTABLES Pages 1-144 PAGES ISSUE DATE 1-12 No.1 September, 1976 13-24 No.2 October, 1976 25-36 No.3 November, 1976 37-48 No.4 December, 1976 49-60 No.5 January, 1977 61-72 No.6 February, 1977 & Kovel On became Ralph Terry Antiques Kovels 73-84 No.7 March,1977 On and Antiques Collectables in April, 1977 (Vol. 85-96 No.8 April,1977 3, No.8). , 97-108 No.9 May, 1977 Amberina glass, 91 109-120 No� 10 June, 1977 Americana, 17 121-132 No.l1 July, 1977 American Indian, 30 133-144 No. 12 August, 1977 American Numismatic Association Convention, 122 Anamorphic Art, 8 Antique Toy World, 67 in Katherine ART DECO Antiques Miniature, by Morrison McClinton, 105 Furniture, 38, 88 Autumn The 0 Glass, 88 Leaf Story, by J Cunningham, 35 Metalwork, 88 Avons other Dee Bottles-by any name, by Sculpture, 88 Schneider, 118 Art 42 Nouveau, 38, Avons Award Bottles, Gifts, Prizes, by Dee' Art Nouveau furniture, 38 Schneider, 118 "Auction 133 & 140 Avons Fever," Bottles Research and History, by Dee 118 Autographs, 112 Schneider, Avons Dee 118 Banks, 53 Congratulations, -by Schneider, Avons President's Club Barometers, 30 History, Jewelry, by Bauer 81 Dee 118 pottery, Schneider, Bauer- The California Pottery Rainbow, by Bottle Convention, 8 Barbara Jean Hayes, 81 Bottles, 61 The Beer Can-A Complete Guide to Collecting, Books, 30 by the Beer Can Collectors of America, 106 BOOKS & PUBLICATIONS REVIEWED The Beer Can Collectors News Report, by the Abage Enclyclopedia of Bronzes, Sculptors, & Beer Can Collectors of America, 107 Founders, Volumes I & II, by Harold A Beginner's Guide to Beer Cans, by Thomas Berman, 52 Toepfer, 106 American Beer Can Encyclopedia, by Thomas The Belleek Collector's Newsletter the ' by Toepfer, 106 Belleek Collector's Club, 23- American Copper and Brass, by Henry J. -

Key Bus Routes in Central London

Route 8 Route 9 Key bus routes in central London 24 88 390 43 to Stoke Newington Route 11 to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to to 73 Route 14 Hill Fields Archway Friern Camden Lock 38 Route 15 139 to Golders Green ZSL Market Barnet London Zoo Route 23 23 to Clapton Westbourne Park Abbey Road Camden York Way Caledonian Pond Route 24 ZSL Camden Town Agar Grove Lord’s Cricket London Road Road & Route 25 Ground Zoo Barnsbury Essex Road Route 38 Ladbroke Grove Lisson Grove Albany Street Sainsbury’s for ZSL London Zoo Islington Angel Route 43 Sherlock Mornington London Crescent Route 59 Holmes Regent’s Park Canal to Bow 8 Museum Museum 274 Route 73 Ladbroke Grove Madame Tussauds Route 74 King’s St. John Old Street Street Telecom Euston Cross Sadler’s Wells Route 88 205 Marylebone Tower Theatre Route 139 Charles Dickens Paddington Shoreditch Route 148 Great Warren Street St. Pancras Museum High Street 453 74 Baker Regent’s Portland and Euston Square 59 International Barbican Route 159 Street Park Centre Liverpool St Street (390 only) Route 188 Moorgate Appold Street Edgware Road 11 Route 205 Pollock’s 14 188 Theobald’s Toy Museum Russell Road Route 274 Square British Museum Route 390 Goodge Street of London 159 Museum Liverpool St Route 453 Marble Lancaster Arch Bloomsbury Way Bank Notting Hill 25 Gate Gate Bond Oxford Holborn Chancery 25 to Ilford Queensway Tottenham 8 148 274 Street Circus Court Road/ Lane Holborn St. 205 to Bow 73 Viaduct Paul’s to Shepherd’s Marble Cambridge Hyde Arch for City Bush/ Park Circus Thameslink White City Kensington Regent Street Aldgate (night Park Lane Eros journeys Gardens Covent Garden Market 15 only) Albert Shaftesbury to Blackwall Memorial Avenue Kingsway to Royal Tower Hammersmith Academy Nelson’s Leicester Cannon Hill 9 Royal Column Piccadilly Circus Square Street Monument 23 Albert Hall Knightsbridge London St. -

SORS-2021-1.2.Pdf

Office of Fellowships and Internships Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC The Smithsonian Opportunities for Research and Study Guide Can be Found Online at http://www.smithsonianofi.com/sors-introduction/ Version 1.1 (Updated August 2020) Copyright © 2021 by Smithsonian Institution Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 How to Use This Book .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Anacostia Community Museum (ACM) ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 Archives of American Art (AAA) ....................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Asian Pacific American Center (APAC) .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage (CFCH) ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum (CHNDM) ............................................................................................................................. -

LOTNUM LEAD DESCRIPTION 1 Sylvester Hodgdon "Castle Island" Oil on Canvas 2 Hampshire Pottery Green Handled Vase 3

LOTNUM LEAD DESCRIPTION 1 Sylvester Hodgdon "Castle Island" oil on canvas 2 Hampshire Pottery Green Handled Vase 3 (2) Pair of Brass Candlesticks 4 (2) Cast Iron Horse-Drawn Surrey Toys 5 (4) Glass Pieces w/Lalique 6 18th c. Tilt-Top Table 7 (2) Black Painted Children's Chairs 8 Corner Chair 9 Vitrine Filled with (21) Jasperware Pieces and Planter 10 Bannister Back Armchair 11 (4) Pieces of Colored Art Glass 12 (8) Pieces of Amethyst Glass 13 "Ship Mercury" 19thc. Port Painting 14 (18) Pieces of Jasperware 15 Inlaid Mahogany Card Table 16 Lolling Chair with Green Upholstery 17 (8) Pieces of Cranberry Glass 18 (2) Child's Chairs (1) Caned (1) Painted Black 19 (16) Pieces of Balleek China 20 (13) Pieces of Balleek China 21 (32) Pieces of Balleek China 22 Over (20) Pieces of Balleek China 23 (2) Foot Stools with Needlepoint 24 Table Fitted with Ceramic Turkey Platter 25 Pair of Imari Lamps 26 Whale Oil Peg Lamp 27 (2) Blue and White Export Ceramic Plates 28 Michael Stoffa "Thatcher's Island" oil w/ (2) other Artworks 29 Pair of End Tables 30 Custom Upholstered Sofa 31 Wesley Webber "Artic Voyage 1879" oil on canvas 32 H. Crane "Steam Liner" small gouache 33 E. Sherman "Steam Liner in Harbor" oil on canvas board 34 Oil Painting "Boston Light" signed FWS 35 Pair of Figured Maple Chairs 36 19th c. "Ships Sailing off Lighthouse" oil on canvas 37 Pate Sur Pate Cameo Vase 38 (3) Framed Artworks 39 (3) Leather Bound Books, Box and Pitcher 40 Easy Chair with Pillows 41 Upholstered Window Bench 42 Lot of Games 43 Rayo-Type Electrified Kerosene Lamp 44 Sextant 45 (11) Pieces of Fireplace Equipment and a Brass Bucket 46 (9) Pieces of Glass (some cut) 47 High Chest 48 Sewing Stand 49 (3) Chinese Rugs 50 "Lost at Sea" oil on canvas 51 Misc. -

Rothesay March 13Th Word Count: 568 Visual Attention 1 2 Given That Our

Rothesay March 13th Word count: 568 1 Visual Attention 2 3 Given that our visual attention has limited resources, we selectively attend to areas that 4 contain salient stimuli (Wolfe & Horowitz, 2004) or that match our internal goals (Hopfinger, 5 Buonocore, & Mangun, 2000). At the same time, other areas in the visual display are often 6 overlooked. Thus, a designer should carefully consider drawing viewers’ attention to important 7 information and reducing viewers’ attentional load on unimportant information. 8 Web designers recently tend to present all the information on a long page, and the 9 viewers need to scroll down to see different blocks of information. This new trend is probably 10 due to frequent mobile device use in our daily life, and we become more familiar with scrolling. 11 A critical piece of information on this type of webpage is to notify people to scroll down. 12 Otherwise, this design would be a complete failure. To successfully deliver this message, 13 designers can use preattentive features, such as motion, to draw people’s attention. For example, 14 on Google Drive’s webpage, the down arrow at the bottom of page informs people to scroll 15 down. Although the color makes the down arrow to stand out from the background, the 16 additional movement of the arrow is the key factor that draws people’s attention. Thus, dynamic 17 arrows can be useful to draw people’s attention to scroll down. 18 If a webpage is filled with dynamic objects, it will create competition between 19 information. To avoid this issue, other methods should be used to draw viewers’ attention. -

Issue 183 Winter 2014/15

CAMBERWELL QUARTERLY The magazine of the Camberwell Society No 183 Winter 2014/15 £1.50 (free to members) www.camberwellsociety.org.uk Perk up your park – p9 Planning Enforcement – p4 The Huguenots of Camberwell – p7 Contents Gazette Report from the Chair ............3 LOCAL SOCIETIES, VENUES AND EVENTS Planning enforcement ............4 We recommend checking details Great expectations for Camberwell art ......................6 Brunswick Park Neighbourhood Nunhead Cemetery Tenants and Residents Association Linden Grove, SE15. Friends of Huguenots of Camberwell ....7 Jason Mitchell 07985 548 544 Nunhead Cemetery (FONC) Perk up your park ..................9 [email protected] 020 8693 6191 www.fonc.org.uk Viet Café Review ................12 Burgess Park, Friends of Green Dale ..........................14 For meetings, events and updates on Peckham Society Burgess Park improvements Peter Frost 020 8613 6757 News ....................................15 www.friendsofburgesspark.org.uk Sunday 15 February, 3pm, Recent [email protected] archaeological finds in Southwark. Community Council: Arts, Meet at St John’s Church, charts and housing starts ......16 Butterfly Tennis Club Goose Green www.butterflytennis.com www.peckhamsociety.org.uk and TU BE or not TU BE ....17 Planning comments..............18 Camberwell Gardens Guild Ruskin Park, Friends of Membership enquiries to: Doug Gillies 020 7703 5018 Directory ..............................19 Pat Farrugia, 17 Kirkwood Road, SE15 3XT SE5 Forum SE5Forum.org.uk THE CAMBERWELL Carnegie Library, Friends of [email protected] SOCIETY See the Friends’ tray in the Library or MEMBERSHIP & EVENTS [email protected] South London Gallery 65 Peckham Road SE5. Open: Concerts in St Giles’Church Tuesday to Sunday – 12pm-6pm, Membership is open to anyone Camberwell Church Street closed on Monday who lives, works, or is interested [email protected] www.southlondongallery.org in Camberwell. -

List of Articles

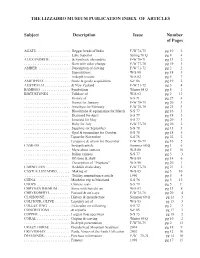

THE LIZZADRO MUSEUM PUBLICATION INDEX OF ARTICLES Subject Description Issue Number of Pages AGATE. .. Beggar beads of India F-W 74-75 pg 10 2 . Lake Superior Spring 70 Q pg 8 4 ALEXANDRITE . & Synthetic alexandrite F-W 70-71 pg 13 2 . Gem with color change F-W 77-78 pg 19 1 AMBER . Description of carving F-W 71-72 pg 2 2 . Superstitions W-S 80 pg 18 5 . in depth treatise W-S 82 pg 5 7 AMETHYST . Stone & geode acquisitions S-F 86 pg 19 2 AUSTRALIA . & New Zealand F-W 71-72 pg 3 4 BAMBOO . Symbolism Winter 68 Q pg 8 1 BIRTHSTONES . Folklore of W-S 93 pg 2 13 . History of S-S 71 pg 27 4 . Garnet for January F-W 78-79 pg 20 3 . Amethyst for February F-W 78-79 pg 22 3 . Bloodstone & aquamarine for March S-S 77 pg 16 3 . Diamond for April S-S 77 pg 18 3 . Emerald for May S-S 77 pg 20 3 . Ruby for July F-W 77-78 pg 20 2 . Sapphire for September S-S 78 pg 15 3 . Opal & tourmaline for October S-S 78 pg 18 5 . Topaz for November S-S 78 pg 22 2 . Turquoise & zircon for December F-W 78-79 pg 16 5 CAMEOS . In-depth article Summer 68 Q pg 1 6 . More about cameos W-S 80 pg 5 10 . Italian cameos S-S 77 pg 3 3 . Of stone & shell W-S 89 pg 14 6 . Description of “Neptune” W-S 90 pg 20 1 CARNELIAN . -

(Together “Knife Rights”) Respectfully Offer the Following Comments In

Knife Rights, Inc. and Knife Rights Foundation, Inc. (together “Knife Rights”) respectfully offer the following comments in opposition to the proposed rulemaking revising the rule for the African elephant promulgated under § 4(d) of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (“ESA”) (50 C.F.R. 17.40(e)) by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (“the Agency”). Docket No. FWS–HQ–IA–2013–0091; 96300–1671–0000–R4 (80 Fed. Reg. 45154, July 29, 2015). Knife Rights represents America's millions of knife owners, knife collectors, knifemakers, knife artisans (including scrimshaw artists and engravers) and suppliers to knifemakers and knife artisans. As written, the proposed rule will expose many individuals and businesses to criminal liability for activities that are integral to the legitimate ownership, investment, collection, repair, manufacture, crafting and production of knives. Even where such activities may not be directly regulated by the proposed rule, its terms are so vague and confusing that it would undoubtedly lead to excessive self-regulation and chill harmless and lawful conduct. The Agency’s proposed revisions to the rule for the African Elephant under section 4(d) of the ESA (“the proposed rule”) must be withdrawn, or in the alternative, significantly amended to address these terminal defects: (1) Violations of the Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”) (Pub. L. 79–404, 60 Stat. 237) and 5 U.S.C. § 605(b) of the Regulatory Flexibility Act (“RFA”); (2) Violation of the Federal Data Quality Act (aka Information Quality Act) (“DQA”/”IQA”) (Pub. L. 106–554, § 515); (3) Violation of Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act (“SBREFA”)(Pub. -

Oware/Mancala) Bonsai Trees

Carved game boards (Oware/Mancala) Bonsai Trees Raw glass dishware sintered rusted moodust “Luna Cotta” Hewn and carved basalt water features INDEX MMM THEMES: ARTS & CRAFTS (Including Home Furnishings and Performing Arts) FOREWORD: Development of Lunar Arts & Crafts with minimal to zero reliance on imported media and materi- als will be essential to the Pioneers in their eforts to become truly “At Home” on the Moon. Every fron- tier is foreign and hostile until we learn how to express ourselves and meet our needs by creative use of local materials. Arts and Crafts have been an essential “interpretive” medium for peoples of all lands and times. Homes adorned with indigenous Art and Crafts objects will “interpret” the hostile outdoors in a friendly way, resulting in pioneer pride in their surroundings which will be seen as far less hostile and unforgiving as a result. At the same time, these arts and crafts, starting as “cottage industries.” will become an important element in the lunar economy, both for adorning lunar interiors - and exteriors - and as a source of income through sales to tourists, and exports to Earth and elsewhere. Artists love free and cheap materials, and their pursuits will be a part of pioneer recycling eforts. From time immemorial, as humans settled new parts of Africa and then the continents beyond, development of new indigenous arts and crafts have played an important role in adaptation of new en- vironments “as if they were our aboriginal territories.” In all these senses, the Arts & Crafts have played a strong and vital second to the development of new technologies that made adaptation to new frontiers easier. -

Full List of Publications for Sale

Publications for Sale At Southwark Local History Library and Archive The Neighbourhood Histories series: Illustrated A5-size histories of the communities within the London Borough of Southwark: The Story of the Borough by Mary Boast £1.95 Covers Borough High Street, and the parishes of St George the Martyr and Holy Trinity The Story of Walworth by Mary Boast £4.00 Covers the parish of St Mary Newington, the Elephant and Castle and the Old Kent Road The Story of Rotherhithe by Stephen Humphrey £3.50 Covers the parish of St Mary Rotherhithe, Surrey Docks, Southwark Park The Story of Camberwell by Mary Boast £3.50 Covers the Parish of St Giles Camberwell, Burgess Park, Denmark Hill The Story of Dulwich by Mary Boast £2.00 Covers the old village and Dulwich Picture Gallery The Story of Peckham and Nunhead by John Beasley £4.00 Covers Rye Lane, houses, Peckham Health Centre, World War I and II and people @swkheritage Southwark Local History Library and Archive 211 Borough High Street, London SE1 1JA southwark.gov.uk/heritage Tel: 020 7525 0232 [email protected] Southwark: an Illustrated History by Leonard Reilly £6.95 An overview of Southwark’s History, lavishly illustrated with over 100 views, many in colour Southwark at War, ed. By Rib Davis and Pam Schweitzer £2.50 A collection of reminiscences from the Second World War which tells the Story of ordinary lives during this traumatic period. Below Southwark by Carrie Cowan £4.95 A 46-page booklet showing the story of Southwark, revealed by excavations over the last thirty years. -

PO Box 957 (Mail & Payments) Woodbury, CT 06798 P

Woodbury Auction LLC 710 Main Street South (Auction Gallery & Pick up) PO Box 957 (Mail & Payments) Woodbury, CT 06798 Phone: 203-266-0323 Fax: 203-266-0707 April Connecticut Fine Estates Auction 4/26/2015 LOT # LOT # 1 Handel Desk Lamp 5 Four Tiffany & Co. Silver Shell Dishes Handel desk lamp, base in copper finish with Four Tiffany & Co. sterling silver shell form interior painted glass shade signed "Handel". 14 dishes, monogrammed. 2 7/8" long, 2 1/2" wide. 1/4" high, 10" wide. Condition: base with Weight: 4.720 OZT. Condition: scratches. repairs, refinished, a few interior edge chips, 200.00 - 300.00 signature rubbed. 500.00 - 700.00 6 Southern Walnut/Yellow Pine Hepplewhite Stand 2 "The Gibson" Style Three Ukulele Southern walnut and yellow pine Hepplewhite "The Gibson" style three ukulele circa stand, with square top and single drawer on 1920-1930. 20 3/4" long, 6 3/8" wide. square tapering legs. 28" high, 17" wide, 16" Condition: age cracks, scratches, soiling, finish deep. Condition: split to top, lacks drawer pull. wear, loss, small edge chips to top. 1,000.00 - 200.00 - 300.00 1,500.00 7 French Marble Art Deco Clock Garniture 3 Platinum & Diamond Wedding Band French marble Art Deco three piece clock Platinum and diamond wedding band containing garniture with enamel dial signed "Charmeux twenty round diamonds weighing 2.02 carats Montereau". 6 1/2" high, 5" wide to 9 3/4" high, total weight. Diamonds are F color, SI1 clarity 12 1/2" wide. Condition: marble chips, not set in a common prong platinum mounting. -

BOOTH # EXHIBITOR DESCRIPTION __ North Sandusky Between William and Winter Streets

BOOTH # EXHIBITOR DESCRIPTION __ North Sandusky between William and Winter Streets — Booths Facing East 1 STAINLESS STEEL ART Sculpture 2 & 3 COOL TIE DYE OSU Tie Dye, etc. 4 SUPREME ACCENTS Quilting 5 KYLEEMAE DESIGNS Unique Jewelry from Repurposed Items 6 J FETZER POTTERY Stoneware & Horsehair Pottery 7 & 8 COLADA CO. Original Women's Clothing 9 CALLIGRAPHY and COLLAGE Inspirational Quotations 10 VARU HANDBAGS Handbags & Accessories 11 DAN PHIBBS Hand Tie Dyed Clothing 12 CONTEMPORARY GLASSWORKS Fused Glass & Jewelry 13 & 14 ENCORE ENVIE BOOTIQUE Recycled & Upscale Boutique Items 15 MURPHY'S WOOD SHOP Boxes, Boards & Pepper Mills 16 RUSTIC APPLE ART Metal License Plate Art 17 JIM WECKBACHER Caricature Drawing 18 MAYFLY PRINTSHOP & TEXTILE LAB Nature Printed Clothing & Printmaking 19 COURTNEY B DESIGNS Lamp work & Wire Weave Jewelry 20 WOOD BUTCHER Wood Art & Animal Puzzles 21 KID STUDIO Mixed Media Sculpture & Frames 22 JEWELRY WITH A PAST Jewelry incorporating Antique Buttons 23 GLO GLASS Hand Blown Glass 24 PEOPLE IN NEED Local Non-Profit Organization 25 TIN TREASURES Tin Cookie Cutters, Birdhouses, etc. 26 PAPAW'S WORKSHOP Benches, Boxes, Barn wood Flag, etc. 27 MEGARA WILD FINE ART & DESIGN Canvas & Animal Skull Paintings 28 UNCOMMON UNIQUE ECLECTIC JEWELRY Chain Maille, Beaded & Wire wrapped 29 HEEKIN PEWTER CO. Pewter Sculpture 30 BATIK CREATIONS Batik Apparel The DELAWARE GAZETTE Information Booth SPONSOR North Sandusky between Winter Street and Central Avenue - Booths Facing East 31 JENEEN HOBBY Fine Art Color Photography 32 SCRIMSHAW by MARK THORGERSON Scrimshaw Jewelry, etc. 33 CENTRAL OHIO SYMPHONY Local Non-Profit Organization 34 & 35 LITTLE CREEK CANDLES Folk Art Candles & Metal craft 36 SUSAN ROCKS ! Items Created from Great Lakes Stone 37 LANFORD BEADWORKS Jewelry from Hand Made Glass Beads 38 & 39 3S CRAFTWORKS Wood items made from Bourbon Barrels 40 CW CANVAS PRINTING Art Printed on Canvas 41 DAVID W BORDINE Stained Glass Window Art 42 MELLISA O'BRIEN DESIGNS Fabricated Sterling Silver Jewelry 43 & 44 J.