Churches, Covid-19 and Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Church of England Around Staffordshire, Northern Shropshire and the Black Country Tgithe Mondaybishop’S Launch Lent Appeal I Was a Stranger

Spotlight Jan/Feb 2017 This year’s Lent Book is in 2017’s Bishop’s Lent Appeal, [see page 3] ‘Dethroning Mammon: raising funds to support refugees and asylum Making Money Serve seekers, people forced out of stable societies Grace’ just published and still left financially excluded when they by the Archbishop of reach a place of safety.” Canterbury, Justin Welby. Following the Gospels towards Easter, “I was really encouraged Dethroning Mammon reflects on the impact to hear there was a great of our attitudes, and of the pressures that uptake of the 2016 Lent surround us, on how we handle the power Book across the Diocese,” of money. Who will be on the throne of says Bishop Michael. our lives? Who will direct our actions and “And there’s a real benefit attitudes? Is it Jesus Christ, who brings in focusing on particular truth, hope and freedom? Or is it Mammon, themes for a season. so attractive, so clear, but leading us into Grace and Money “So the 2017 Lent paths that tangle, trip and deceive? Archbishop book follows on Justin encourages us to use Lent as a time of from last autumn’s learning to trust in the abundance and grace of God. Selwyn Lecture in looking at our Dethroning Mammon features study questions attitudes to money suitable for small groups. In addition, the Diocese and the effects is producing study materials for young people. It is it has on us and available for order until 27 January 2017 from the Andy Walton from the society around us. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Thursday Volume 582 12 June 2014 No. 6 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Thursday 12 June 2014 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2014 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 671 12 JUNE 2014 672 However, we will examine method of slaughter labelling House of Commons when the European Commission produces its report, which is expected in the autumn. Thursday 12 June 2014 Albert Owen (Ynys Môn) (Lab): Farmers and food producers raise the issue of labelling often with me and The House met at half-past Nine o’clock other Members. Can the Minister assure the House that his Department is doing everything it can to have clear PRAYERS labelling on all packaging, particularly after the horsemeat crisis and various other issues, so that we can have country of origin and even region of origin labelling on [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] our packaging? BUSINESS BEFORE QUESTIONS George Eustice: Some new labelling requirements from the European Union have just been put in place, to SPOLIATION ADVISORY PANEL distinguish between animals that are born, reared and Resolved, slaughtered in a particular country, reared and slaughtered That an humble Address be presented to Her Majesty, That there or simply slaughtered there. That is a major she will be graciously pleased to give directions that there be laid improvement. We have stopped short of having compulsory before this House a Return of the Report from Sir Donnell country of origin labelling on processed foods, because Deeny, Chairman of the Spoliation Advisory Panel, dated 12 June the European Commission report suggested that it would 2014, in respect of a painted wooden tablet, the Biccherna Panel, now in the possession of the British Library.—(John Penrose.) be incredibly expensive to implement. -

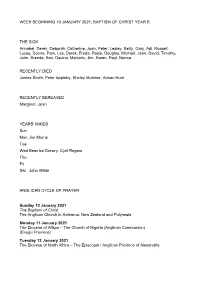

Week Beginning 10 January 2021; Baptism of Christ Year B

WEEK BEGINNING 10 JANUARY 2021; BAPTISM OF CHRIST YEAR B THE SICK Annabel, Derek, Deborah, Catherine, Joan, Peter, Lesley, Betty, Gary, Adi, Russell, Lucas, Donna, Pam, Les, Derek, Freda, Rosie, Douglas, Michael, Jean, David, Timothy, John, Brenda, Ken, Davina, Malcolm, Jim, Karen, Paul, Norma RECENTLY DIED James Smith, Peter Appleby, Shirley Mutimer, Adrian Hunt RECENTLY BEREAVED Margaret, Jean YEARS’ MINDS Sun Mon Jim Morris Tue Wed Beatrice Drewry, Cyril Rogers Thu Fri Sat John White ANGLICAN CYCLE OF PRAYER Sunday 10 January 2021 The Baptism of Christ The Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia Monday 11 January 2021 The Diocese of Afikpo – The Church of Nigeria (Anglican Communion) (Enugu Province) Tuesday 12 January 2021 The Diocese of North Africa – The Episcopal / Anglican Province of Alexandria Wednesday 13 January 2021 The Diocese of the Horn of Africa – The Episcopal / Anglican Province of Alexandria Thursday 14 January 2021 The Diocese of Agra – The (united) Church of North India Friday 15 January 2021 The Diocese of Aguata – The Church of Nigeria (Anglican Communion) (Niger Province) Saturday 16 January 2021 The Diocese of Ahoada – The Church of Nigeria (Anglican Communion) (Niger Delta Province) Information regarding Coronavirus from the Church of England including helpful prayer and liturgical resources can be accessed at: https://bit.ly/33PHxMZ LICHFIELD DIOCESE PRAYER DIARY – DISCIPLESHIP, VOCATION, EVANGELISM Sunday 10thJanuary: (William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, 1645) For our Diocesan Bishop, Rt Revd Dr Michael Ipgrave; for members of the Bishop’s Staff team including Rt Revd Clive Gregory, Area Bishop of Wolverhampton; the Ven Matthew Parker, Area Bishop of Stafford (elect); Rt Revd Sarah Bullock, Area Bishop of Shrewsbury and all Archdeacons; for Canon Julie Jones, Chief Executive Officer and Diocesan Secretary as she heads the administrative team and implementation of Diocesan strategy; for the Very Revd Adrian Dorber, Dean of Lichfield and head of Lichfield Cathedral and Revd Dr Rebecca Lloyd, Bishop's Chaplain. -

A Prayer on the Anniversary of the First Moon Landing

The Church of England is marking the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing with the publication of a special prayer, as events take place around the world to celebrate the event. The prayer, which is being shared on social media, speaks of man’s drive to “explore the mysteries of creation” and the need to cherish our world. Churches and cathedrals across England are marking the anniversary with special events. At Lichfield Cathedral, One Small Step, a 36 metre artwork replica of the lunar surface opens on Saturday morning – the anniversary of the landing - giving visitors the chance to ‘walk on the moon’ until the end of September. Also on Saturday, Birmingham Cathedral is hosting two showings of ‘Interstellar’, an immersive sound and light show celebrating the moon landing. The Bishop of Kingston, Richard Cheetham, who is a Co-Director of Equipping Christian Leadership in an Age of Science, a project to promote greater understanding between science and faith, encouraged churches to use the anniversary of the moon landing as an opportunity for prayer and reflection. “After decades of space travel, including the iconic moon landing 50 years ago, we are more aware than ever of the vastness and complexity of the cosmos,” he said. “Living, as we do, in a scientific age it is vital that our understanding and practice of Christian faith celebrates and engages deeply with the huge potential which science brings to our understanding of the universe, and ensures it is used wisely. “The Equipping Christian leadership in an Age of Science project has sought to help the church to do that in many ways. -

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2015-2016

The College of St Barnabas z Caring for retired Anglican Clergy since 1895 1 Front cover: “The St Barnabas Home for Retired Clergymen’s May Day Celebrations” by William Isaacs 2 The College of St Barnabas Registered Company Office: Blackberry Lane, Lingfield, Surrey, RH7 6NJ Tel 01342 870260 Fax 01342 871672 Registered Company number: 61253 Registered Charity number: 205220 Report of the Council for the year ended 31 August 2016 The Council presents its report with financial statements for the year ended 31 August 2016. The Council has adopted the provisions of the Statement of Recommended Practice (SORP) 'Accounting and Reporting by Charities' issued in March 2015. Contents 3 Who’s Who 4 Patrons and Presidents 5 The Members of the Council 7 From the Chairman 8 A Review of the Year Residents 10 Faith and Worship 12 Publicity 13 Social Activities 14 The College and the Wider Community 15 Achievement and Performance Occupancy of the College 16 Internal Maintenance 16 Fundraising 17 Financial Review 18 Structure, Governance and Management Constitution and Function 20 Governing Procedures 21 Risk Management 21 Membership of Committees 22 Professional Advisers 22 Report of the Investment Adviser 23 Report of the Independent Auditors 24 Financial Statements for the Year ended 31 August 26 2016 Parochial Church Councils and other organisations 42 who have supported the College Trusts who have supported the College 43 3 Who’s Who Visitor: The Right Reverend the Lord Bishop of Southwark (Ex-Officio) Members of Council: Sir Paul Britton, CB, CVO -

Archbishop: Living Wage Revelations Are ‘Embarrassing’

THE ORIGINAL CHURCH NEWSPAPER. ESTABLISHED IN 1828 Renewing THE Debating the the Church Green of England, Report: P8 CHURCHOF ENGLAND P9 Newspaper NOW AVAILABLE ON NEWSSTAND FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 27, 2015 No: 6268 Archbishop: Living Wage revelations are ‘embarrassing’ THE ARCHBISHOP of Canterbury, the Most Rev employers seeking to implement the pay level pro- Justin Welby, has distanced himself from the inner gressively. What is important is that those who can, workings of his church by calling reports that the do so, as soon as is practically possible. The vast Church of England is advertising jobs at less than majority of those employed by or sub-contracted to the Living Wage ‘embarrassing.’ the Church’s central institutions are already paid at The Sun on Sunday reported that both Canterbury least the Living Wage and all will be by April 2017. and Lichfield Dioceses have advertised jobs but “Each of our 12,000 parishes, dioceses and cathe- offering pay under the £7.85 Living Wage standard, drals is a separate legal entity with trustees and has supported as the minimum expected wage in the to act in the light of its own circumstances. House of Bishops’ Pastoral Letter. “As charities churches require time to increase Speaking to an audience on his four-day visit to giving levels prior to ensuring delivery of the living Birmingham, Archbishop Welby said: “We talked wage. about the need to move towards that, and Archbish- “We are grateful to The Sun and others for high- op of York John Sentamu carefully said that we need lighting the sound principles behind the living wage to move towards paying the Living Wage. -

University of Leeds Catalogue of the Correspondence and Papers of the Rt Hon Edward Charles Gurney Boyle, Baron Boyle of Handswo

Handlist 81 part 2 UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS CATALOGUE OF THE CORRESPONDENCE AND PAPERS OF THE RT HON EDWARD CHARLES GURNEY BOYLE, BARON BOYLE OF HANDSWORTH, C H (1923 - 1981) Part 2 (Index) Leeds University Special Collections MS 660 Aaronovitch, David, Vice-President NUS: letter from, 50831 Abbott, Eric Symes, Dean of Westminster: correspondence, 48500, 48503 48898- 48900, 48902, 48904, 49521, 49524 Abbott, Frank, chairman ILEA: correspondence, 38825, 47821-2 Abbott, Gill, chairman Liverpool NUS Committee: correspondence, 26830-3, 26839, 26841 Abbott, J R, secretary Nottingham & District Manufacturers' Association: letter from, 26638 Abbott, Joan, sociologist: correspondence, 8879, 8897, 8904 Abbott, Simon, Editor Race: correspondence, 37667-9, 47775-6 Abbott, Stephen: paper by, 23426, 23559 Abbott, Walter M, Editor America: letter from, 4497 Abel, Deryck, Free Trade Union : correspondence, 3144, 3148 Abel, K A, Clerk Dorset CC: letter to Oscar Murton, 23695 Abel Smith, Henriette Alice: correspondence, 5618, 5627 Abercrombie, Nigel James: correspondence, 18906, 18924, 34258, 34268-9, 34275, 34282, 34292-3, 34296-8, 34302, 34305, 34307-8, 34318-20; Copy from Harold Rossetti, 34274; Copies correspondence with Sir Joseph Lockwood, 34298, 34303 Aberdare, 4th baron: see Bruce, Morys George Lyndhurst Abhyankhar, B, Indian Association: correspondence, 9951, 9954-6 Ablett, R G, Hemsworth High School, Pontefract: letter from, 45683 Abolition of earnings rule (widowed mothers): 14935, 14938 14973-4, 15015, 15034, 16074, 16100, 16375, 16386 Abortion: -

A Community of Retired Anglicans Uniting in Faith and Care

Objectives The College of St Barnabas z A Community of retired Anglicans uniting in Faith and Care 1 The College of St Barnabas Registered Company Office: Blackberry Lane, Lingfield, Surrey, RH7 6NJ Tel 01342 870 260 Fax 01342 871 672 Registered Company number: 61253 Registered Charity number: 205220 Report of the Council for the year ended 31 August 2018 Contents Who’s Who 3 Patrons and Presidents 4 The Members of the Council 5 The Chairman’s Foreword 6 A Review of the Year Residents 8 Prayer, Worship and Celebration 9 Patronal Festival, Quiet Days and Lent Addresses 10 Nursing Wing, Buildings, Farewell 11 Publicity 12 The College and the Wider Community 12 The Friends of the College 13 Achievement and Performance Occupancy of the College 13 Fundraising 14 Financial Review 15 Structure, Governance and Management 17 Membership of Committees 20 Professional Advisers 20 Report of the Investment Adviser 21 Statement of Trustees’ Responsibilities 23 Report of the Independent Auditors 24 Financial Statements for the Year ended 31 August 27 2018 Parochial Church Councils and other organisations 46 which have supported the College Trusts which have supported the College 47 Front cover: Rainbow over the West wing of the College 2 Who’s Who Visitor: The Right Reverend the Lord Bishop of Southwark (Ex-Officio) Members of Council: Sir Paul Britton, CB, CVO (Chairman) Mrs Vivien Hepworth, BA (Hons) (Vice-Chairman) The Venerable Moira Astin, BA, MA (Ex-Officio) Mr Peter Beynon, BA, CEng MICE Mr Richard Diggory, BA (Hons) Mr David Jessup, BSc (Hons), -

The 99Th Bishop of Lichfield the Right Reverend Dr Michael Ipgrave Has St Chad, a Man of Great Humility and Profound Been Named As the Next Bishop of Lichfield

The Diocese of Lichfield Magazine Mar/Apr 2016 The 99th Bishop of Lichfield The Right Reverend Dr Michael Ipgrave has St Chad, a man of great humility and profound been named as the next Bishop of Lichfield. Christian faith.” Bishop Michael (57), the current Bishop of His appointment was announced on 2 March Woolwich in the Diocese of Southwark, will be and was greeted in Wolverhampton by Bishop the ninety-ninth Bishop of Lichfield, in a line Clive: “A year ago on St Chad’s Day, Bishop going back to St Chad in the seventh century. Jonathan announced his retirement as Bishop of Lichfield. Today, on St Chad’s Day, we can In a personal welcome message to the Diocese, share the wonderful news that Bishop Michael is Bishop Michael says “I’ve had twelve wonderful joining us here in the West Midlands. He brings years in London but I am so looking forward to with him a rare combination of gifts, as theo- coming back to the Midlands. Lichfield is the logian and teacher, pastor and mission enabler, mother church of the Midlands, and the city of which will greatly enrich our life as a Diocese.” Next to Little Drayton, to meet the Lord The Right Reverend Michael Geoffrey Ipgrave Welcome, Bishop Michael Lieutenant of Shropshire, volunteers at the OBE, MA, PhD grew up in a small village in Market Drayton Food Bank and CAP, clergy Northamptonshire. He studied mathematics Following the announce- of Hodnet Deanery chapter and the team at Oriel College, Oxford, and trained for the ment of Bishop Michael's behind the ministry at Ripon College Cuddesdon, Oxford appointment on the 10 new ‘TGI after a year working as a labourer in a factory Downing Street website, Monday in Birmingham. -

Lichfield Diocesan Prayer Diary W/B 17/06/2018

Lichfield Diocesan Prayer Diary w/b 17/06/2018 th rd Sunday 17 June 3 Sunday after Trinity Global: The Church of the Province of Myanmar –Burma Myint Oo Archbishop of Myanmar and Bishop of Yangon Companion Link: Matlosane, South Africa Join with our brothers and sisters in Matlosane in giving thank for the life of their much loved retired Suffragan Bishop Sigisberth Ndwandwe, who passed on peacefully and was buried following a service at the newly opened Diocesan Centre of Matlosane. Pray for the four Archdeacons: The Ven. Sydney Magobotla (Cathedral AD), The Ven. Motheo William Pooe (Central AD), The Ven. Patrick Botshelo Saunders Mafisa and the Ven. Nontozanele Mogami (South AD); for the effective oversight and operation of our newly formed Matlosane Diocesan Working Party. Revd Philip Swan Local: Lichfield Cathedral of the Blessed Virgin Mary and St. Chad. Pray for the Dean of the Cathedral, the very Revd Adrian Dorber, The Rev Andrew Stead, Canon Precentor and the Revd Pat Hawkins, Canon Chancellor; for the Cathedral departments, staff and all volunteers and for the work, daily life and mission of the Cathedral. Today: Refugee Week www.refugeeweek.org.uk Almighty and merciful God, whose Son became a refugee and had no place to call his own; look with mercy on those who today are fleeing from danger, homeless and hungry. Bless those who work to inspire generosity and compassion in all our hearts; bring them relief; and guide the nations of the world towards that day when all will rejoice in your Kingdom of justice and of peace; through Jesus Christ our Lord. -

Lichfield Diocese Day of Prayer October 23/24

Day of Prayer October 2020 Lichfield Diocese Day of Prayer October 23/24 (The following resources for prayer have been compiled for use during the 24hr Day of Prayer though they can still be used on a daily basis. More details: https://www.lichfield.anglican.org/calendar/event.php?event=161 ) "As we follow Christ in the footsteps of St Chad, we pray that the two million people in our diocese encounter a church that is confident in the gospel, knows and loves its communities, and is excited to find God already at work in the world. We pray for a church that reflects the richness and variety of those communities. We pray for a church that partners with others in seeking the common good, working for justice as a people of hope." Our Diocesan Vision prayer provides the basis for our prayers. Do spend time focussing on and praying through the different parts of this prayer; include local details and adapt it to your context. Sunday 18th October: We pray for our Diocesan Bishop The Rt Revd Dr Michael Ipgrave, for our Area Bishops and Archdeacons – Bishop Clive Gregory (Wolverhampton), Bishop Sarah Bullock, (Shrewsbury) and Bishop elect Matthew Parker (Stafford) and for our Archdeacons - the Ven Dr Sue Weller (Lichfield), the Ven Julian Francis, (Walsall) and the Ven Paul Thomas, (Salop); for our Cathedral – Dean Adrian Dorber and Canons Andrew Stead, Gregory Platten and Jan McFarlane and all involved in the mission and ministry of the Cathedral; for Robert Mountford, Regional Ecumenical Officer and for developing ecumenical relations; for Neil Spiring, our Diocesan Safeguarding Adviser, and his team to ensure that safeguarding is deeply embedded in our church culture and practice. -

Cathedrals and Their Communities

CATHEDRALS AND THEIR COMMUNITIES A report on the diverse roles of cathedrals in modern England Contents Foreword 3 Bridging Communities 6 Helping refugees 7 Supporting the vulnerable 7 At the heart of communities 8 Cathedral Economies 9 Bringing in the crowds 10 Events big and small 11 Cathedrals on screen 13 A home for business 14 Cultural Heritage 15 Architectural splendour 16 Heritage sites 17 Cathedral treasures 17 Conclusion 18 Foreword When I became Minister for Faith in the Department for Communities and Local Government, I decided to set out on a tour of all 42 Anglican cathedrals to celebrate their great work and better understand their role in today’s society. Ahead of the tour, I fully expected to hear that cathedrals face many challenges and struggles. While Britain remains a Christian country, we hear too often of declining congregations, financial problems and fading relevance across our cathedrals. I couldn’t have been more mistaken. I was struck by the vibrancy and creativity of the teams running England’s cathedrals and how chapters are tackling challenges at all levels. From Bishops to Deans, from communications professionals to administrative staff, I feel at the tour’s close that our cathedrals are in very safe hands. The evidence is clear. A 2016 report by the Church of England has shown that England’s cathedrals are attracting more worshippers and diversifying towards new activities and programmes to meet the changing needs of their communities. It is inspiring to see how cathedrals have built upon their traditional congregations in recent years as they engage with our country’s diverse communities.