The Sri Lankan Post-Modern Consumer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

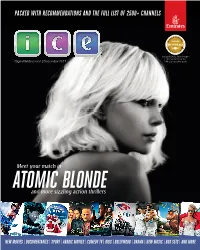

Packed with Recommendations and the Full List of 2500+ Channels

PACKED WITH RECOMMENDATIONS AND THE FULL LIST OF 2500+ CHANNELS Voted World’s Best Infl ight Entertainment for the Digital Widescreen | December 2017 13th consecutive year! Meet your match in ATOMIC BLONDE and more sizzling action thrillers NEW MOVIES | DOCUMENTARIES | SPORT | ARABIC MOVIES | COMEDY TV | KIDS | BOLLYWOOD | DRAMA | NEW MUSIC | BOX SETS | AND MORE OBCOFCDec17EX2.indd 51 09/11/2017 15:13 EMIRATES ICE_EX2_DIGITAL_WIDESCREEN_62_DECEMBER17 051_FRONT COVER_V1 200X250 44 An extraordinary ENTERTAINMENT experience... Wherever you’re going, whatever your mood, you’ll find over 2500 channels of the world’s best inflight entertainment to explore on today’s flight. THE LATEST Information… Communication… Entertainment… Track the progress of your Stay connected with in-seat* phone, Experience Emirates’ award- MOVIES flight, keep up with news SMS and email, plus Wi-Fi and mobile winning selection of movies, you can’t miss movies and other useful features. roaming on select flights. TV, music and games. from page 16 527 ...AT YOUR FINGERTIPS STAY CONNECTED 4 Connect to the 1500 OnAir Wi-Fi network on all A380s and most Boeing 777s 1 Choose a channel Go straight to your chosen programme by typing the channel WATCH LIVE TV 2 3 number into your handset, or use the onscreen channel entry pad Live news and sport channels are available on 1 3 Swipe left and Search for Move around most fl ights. Find out right like a tablet. movies, TV using the games more on page 9. Tap the arrows shows, music controller pad onscreen to and system on your handset scroll features and select using the green game 2 4 Create and Tap Settings to button 4 access your own adjust volume playlist using and brightness Favourites Home Again Many movies are 113 available in up to eight languages. -

Nimal Dunuhinga - Poems

Poetry Series nimal dunuhinga - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive nimal dunuhinga(19, April,1951) I was a Seafarer for 15 years, presently wife & myself are residing in the USA and seek a political asylum. I have two daughters, the eldest lives in Austalia and the youngest reside in Massachusettes with her husband and grand son Siluna.I am a free lance of all I must indebted to for opening the gates to this global stage of poets. Finally, I must thank them all, my beloved wife Manel, daughters Tharindu & Thilini, son-in-laws Kelum & Chinthaka, my loving brother Lalith who taught me to read & write and lot of things about the fading the loved ones supply me ingredients to enrich this life's bitter-cake.I am not a scholar, just a sailor, but I learned few things from the last I found Man is not belongs to anybody, any race or to any religion, an independant-nondescript heaviest burden who carries is the Brain. Conclusion, I guess most of my poems, the concepts based on the essence of Buddhist personal belief is the Buddha who was the greatest poet on this planet earth.I always grateful and admire him. My humble regards to all the readers. www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 * I Was Born By The River My scholar friend keeps his late Grandma's diary And a certain page was highlighted in the color of yellow. My old ferryman you never realized that how I deeply loved you? Since in the cradle the word 'depth' I heard several occasions from my parents. -

Symphony Orchestra of Sri Lanka Westlife

With Chamikara Weerasinghe IN TUNE SATURDAY,SEPTEMBER 5,2009 DN Symphony Orchestra of Sri Lanka presents Classics in Harmony today Abeysekera said about music fans and oriental the concert on being asked classical music fans. ” about the the concert Victor Ratnayaka will whether it be a fusion of sing a set of six songs at Western classical music the Classics in harmony and oriental music, it will concert. Unlike in Western not be a concert of fusion classical music , North of the two great traditions. Indian classical music “ In order to produce recognise voice to be pre- fusion, the two styles have dominant to fashion a Rag. to be blended to produce a According to Sangeeth different sound,” he Ratnakara by Pandit Sar- explained and added ,” nagadeva, music is defined Classics in Harmony will as the combination of vocal stand to complement the President, Sri Lankan Sym- music, instrumental music phony Orchestra, Prof. Ajith two music traditions rather and dance. Nanda Malini Abeysekera than creating “fusion”. It Even without Dance and will preserve the orchestral ern classical music fans to classical music and vice Instrumental music , vocal color of both Western and appreciate Western classi- versa. Singers like Victor music alone can be called Eastern traditions ,” he cal music,” he said. Ratnayaka, Nanda Malini, music. A performer said. ”We do not want to “The concert will ‘not’ W.D.Amaradewa and T.M, should not forget that create a monstrous hybrid be a pop show and the Jayaratna are high caliber voice is predominant in the as such by fusing the two,” experience will be be total- vocalists. -

An Overview About Different Sources of Popular Sinhala Songs

AN OVERVIEW ABOUT DIFFERENT SOURCES OF POPULAR SINHALA SONGS Nishadi Meddegoda Abstract Music is considered to be one of the most complex among the fine arts. Although various scholars have given different opinions about the origin of music, the historical perspectives reveal that this art, made by mankind on account of various social needs and occasions, has gradually developed along with every community. It is a well-known fact that any fine art, whether it is painting, sculpture, dance or music, is interrelated with communal life and its history starts with society. Art is forever changing and that change comes along with the change in those societies. This paper looks into the different sources of contemporary popular Sinhala songs without implying a strict border between Sinhala and non-Sinhala beyond the language used. Sources, created throughout history, deliver not only a steady stream of ideas. They are also often converted into labels and icons for specific features within a given society. The consideration of popularity as an economic reasoning and popularity as an aesthetic pattern makes it possible to look at the different important sources using multiple perspectives and initiating a wider discussion that overcomes narrow national definitions. It delivers an overview which should not be taken as an absolute repertoire of sources but as an open pathway for further explorations. Keywords Popular song, Sinhala culture, Nurthi, Nadagam, Sarala Gee INTRODUCTION Previous studies of music have revealed that first serious discussions and analyses of music emerged in Sri Lanka with the focus on so-called tribal tunes. The tunes of tribes who lived in stone caves of Sri Lanka have got special attention of scholars worldwide since they were believed of being some of the few “unchanged original” tunes. -

Joint Bulletin – Rotaract Club of Bombay West

By Rotaract Club of Bombay West and the Rotaract Club of Achievers Lanka Business School RID 3141 RID 3220 Rotaract Club Of Bombay West, today, is one of the most successful clubs in Mumbai having ranked towards the top in District 3141 repeatedly due to its innovative projects and work ethic of its members. Currently holding the tag of the Best Community Club in Mumbai District. However, every big achievement has its small beginning. Ours began on 19th April 1969 as the youth wing of the prestigious Rotary Club of Bombay West, the first baby club of Rotary Club of Bombay itself! Having been dormant for several years, the club was revived in 2017. With the new generation taking over and with fresh ideas and perspectives, Rotaract Club of Bombay West delivered quality in terms of their projects.Today, Our Signature Projects are known in the district and we strive to maintain the quality at the same standard. The Rotaract Club of Achievers Lanka Business School was chartered on the 10th of March,2010 under our parent club, The Rotary Club of Colombo Mid Town. The club is based in one of the leading ACCA & CIMA tuition providers in Sri Lanka and is the first and only CIMA institute with its own Rotaract Club. The club is now in its 12th year, with many successful projects to its name. Within just 11 years from inception, Rotaract club of Achievers Lanka Business School now stands toe-to-toe with several clubs that have been in existence for approximately 30 years. Despite the relative inexperience, the club, guided by able hands of distinguished past presidents has built up a reputation of carrying out one successful project after the other. -

Western Music

Western Music Grade - 13 Teacher’s Instructional Manual (This syllabus would be implemented from 2010) Department of Aesthetic Education National Institute of Education Maharagama FOREWORD Curriculum developers of the NIE were able to introduce Competency Based Learning and Teaching curricula for grades 6 and 10 in 2007 and were also able to extend it to 7,8 and 11 progressively every year and even to GCE (A/L) classes in 2009. In the same manner syllabi and Teacher's Instructional Manuals for grades 12 and 13 for different subjects with competencies and competency levels that should be developed in students are presented descriptively. Information given on each subject will immensely help the teachers to prepare for the Learning - Teaching situations. I would like to mention that curriculum developers have followed a different approach when preparing Teacher's Instructional Manuals for Advanced Level subjects when compared to the approaches they followed in preparing Junior Secondary and Senior Secondary curricula. (Grades 10,11) In grades 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11 teachers were oriented to a given format as to how they should handel the subject matter in the Learning - Teaching process, but in designing AL syllabi and Teacher's Instructional Manuals freedom is given to the teachres to work as they wish. At this level we expect teachers to use a suitable learning method form the suggested learning methods given in the Teacher's Instructional Manuals to develop competencies and competency levels relevant to each lesson or lesson unit. Whatever the trarning approach the teacher uses it should be done effectively and satisfactorily to realize the expected competencies and competency levels. -

Download the Booklet

1 FOREWORD This volume shares a selection of inspiring stories of a few Dialog Merit Scholars who have travelled beyond boundaries in their quest for timeless and limitless knowledge, finding their way into the world to make a difference. Since its launch in 2003, the Dialog Merit Scholarship Programme, supported by Dialog Axiata PLC, has supported talented and promis- ing students who have emerged as high-flyers at the district and national levels at the G.C.E Ordinary Level and G.C.E Advanced Level Examinations – encouraging them to develop knowledge and skills in the field of engineering. In its efforts to contribute to the develop- ment of the telecommunication industry and the nation building process, the Dialog Scholarship Programme has worked with an emphasis on nurturing talents for the future, providing financial aid and guidance to a cohort of future professionals and leaders in the industry. Over the years, these scholarships have helped students striving for excellence in their education and to carry it on in their lives and careers. Today, as we celebrate more than a decade of the Dialog Merit Scholarship Programme, we take great pride in presenting this volume of stories to commemorate great achievements of these Dialog Scholars who have displayed immense academic excellence, courage, determination and commitment in every aspect in life. The book unveils the amazing life-changing journeys of 40 scholars among over 600 scholars. The profiled individuals reflect Dialog Scholars from different social, cultural, ethnic and religious backgrounds representing each district of the country. This volume gives these scholars the opportunity to express their gratitude to those who stood beside them to support their journey, to emerge victorious as intelligent and knowledgeable individuals. -

Asian-European Music Research

ASIAN-EUROPEAN MUSIC RESEARCH E-JOURNAL No. 3 (Summer 2019) ISSN 2625-378X COTTBUS/BERLIN: WENDISCHER VERLAG ASIAN-EUROPEAN MUSIC RESEARCH E-JOURNAL SPECIAL PRINT No. 3 (Summer 2019) ISSN 2625-378X COTTBUS/BERLIN: WENDISCHER VERLAG AEMR-EJ Editor Xiao Mei, Shanghai Conservatory of Music, [email protected] Reviews Editors Tan Hwee San, SOAS, [email protected] Chuen-Fung Wong, Macalester College, [email protected] Send books, films, links and other materials for review to: Tan Hwee San, Chuen-Fung Wong, Gisa Jähnichen, Xiao Mei Co-Editor Gisa Jähnichen, Shanghai Conservatory of Music [email protected] Editorial Board • Ako Mashino (Dr., Tokyo University of the Arts, Japan) [email protected] • Alexander Djumaev (Dr., Union of Composers of Uzbekistan) [email protected] • Chinthaka P. Meddegoda (Dr., UVPA, Colombo, Sri Lanka) [email protected] • Chow Ow Wei (Dr., Putra University, Malaysia) [email protected] • Earl Jimenez (MA, Philippine Women’s University, Philippines) [email protected] • Esbjörn Wettermark (Dr., Office for Cultural Development Gävleborg, Sweden) [email protected] • Helen Rees (Prof. Dr., UCLA, USA) [email protected] • Liu Hong (Dr., Shanghai Conservatory of Music, China) [email protected] • Xu Xin (Dr., China Conservatory of Music, Beijing, China) [email protected] • Razia Sultanova (Dr., Cambridge University, UK) [email protected] • Tan Shzr Ee (Dr., Royal Holloway, University of London, UK) [email protected] Asian-European Music Research Journal is a peer-reviewed academic journal that publishes scholarship on traditional and popular musics and field work research, and on recent issues and debates in Asian and European communities. -

Winter 2007, Volume 36

Volume 36 Winter 2007 From the President …. Our term has nearly completed, our hearts are content with a sense of The Committee satisfaction. With unity as our main theme for this year we have done our best to bring to you balanced projects representing all ethnic communities living in President: Omar Fahmy (09) 846 9427 New Zealand. We kicked-off with the Mid Winter Dinner Dance at Coral Reef restaurant on the 9th of September with Samba, Rumba and Baila that were just Vice President: too much to resist even for the elderly folk. We changed the venue from the Manjula Walgampola (09) 529 1443 traditional School halls to a restaurant giving more glamour, we kept the cost Secretary: down to thirty dollars, this was a hit, judging from the great feedback we had. Emmanuel Fernando (09) 627 5875 Sadly the dream of a Sri Lankan Community Hall may not be realistic at this juncture. Our commitment to the community was to bring affordable events to Treasurer: you and your family, but not compromising on the tradition Foundation quality. Nalar Mohamed (09) 522 2181 We engaged with you seeking feedback on future publications and events. We Committee Members: offered you opportunities to join our Foundation family that stands for “No Rohan Jayasuriya (09) 523 0922 politics and equality to all Sri Lankan communities in New Zealand. Radhini Sabanayagam (09) 629 3867 LankaNite ’06 was a night to remember, with free entrance thanks to the S. Puvanakumar (09) 624 4343 sponsorship of Spiceland, we had families of all ethnicities mixing and mingling Sarath Pannila (09) 624 6984 celebrating the dawn of the New Year to the live music of Amazonas. -

President's Secretary Opens Refurbished

135th Royal Thomian is on 13, 14, 15 March at S.S.C. For more RCU news updates and events, visit President’s Secretary opens refurbished http://www.rcu.lk/ Primary ICT lab February 19 marks another milestone of a promising journey of learning ICT for primary students of Royal College with the re- opening of the Primary ICT lab. EDEX Expo 2014 Stepping on to its 2nd decade of pioneering leadership, the three day EDEX Expo 2014 concluded on January 19 at BMICH with 40,000 participants visiting over 360 stalls. A Healthy Royal Smile Dental surgeons of Royal College Doctors’ Association (RCDA) initiated an oral health programme themed ‘Healthy Royal Smile’ on January 30. 135th Battle of the Blues In this edition 1. President’s Secretary opens refurbished Primary ICT lab 2. EDEX Expo 2014; 11 years and counting 3. Royal Challenge 2014 4. A healthy Royal Smile 5. Suvinisara, the resonance of classics 6. LP-RCOBANA event creates hope for young Royalists to emulate their seniors 7. Past Royalists in North America guide young Royalists to ‘Win Royal College wins Inter School the World with English’ Commerce Championship 8. RC Stewards gain much from the efforts of the Past Royalists 9. ROCOHA Night 10. Rajakeeya Adyapana Yathra 11. Royal wins Roy - Tho Soccer Encounter 12. Over 600 students benefit from ICT Day 13. RCG ’98 funds a maintenance crew work space Royalists Onstage 2013; Featured the musical talents of Royalists past and present all on one grand stage 2 2014● Volume 7, Issue 4 ● Royal College Union 2014● Volume 7, Issue 4 ● Royal College Union● 3 2014● Volume 7, Issue 4 ● Royal College Union President’s Secretary opens refurbished Primary ICT lab Group of ’93 leads renovation; RCOBAA joins hand February 19 marks another milestone of a promising journey of learning ICT for primary students of Royal College with the re-opening of the Primary ICT lab. -

Feel Negombo Feel It, Experience It and Live It

MUSIC SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 28, 2009 DN Feel Negombo Feel it, Experience it and Live it beaches and there was a request from the people to One of the special highlights of focus on Negombo, to cre- the Fest is the senior citizens ate awareness locally and internationally and to make program where Sri Lankans abroad it a destination point”, will have the opportunity to pay for Minister of Tourism Pro- a day trip for their parents living motion Faiszer Musthapha here. Transport, buffet and various said at a press briefing recently. DEMI HEWAMANNA activities made to entertain them The main attractions of will be all organized for them the night will be beating of eel Negombo 2009, the amazing drums of Ravi an event like no Bandu Vidyapathi, Triloka, F other is getting ready needs more events than it One of the special high- Naardo, Elephant Foot and to sail its away across the has and we have already lights of the Fest is the Hurricane. golden sandy beaches of targeted some cities. senior citizens program The international high- Negombo this Christmas Colombo is known for its where Sri Lankans abroad lights will be from Dj Acee season to give a fun filled Jazz Festival, Galle for the will have the opportunity flying down from Switzer- three days of activities, Literary Festival, to pay for a day trip for land spinning the Hip Hop adventure, music and Hikkaduwa for its Beach their parents living here. round, Dj Miss Match from entertainment suitable for Fest and other cities in the Transport, buffet and vari- Australia will be mixing up the whole family. -

Mediocre Training of Montessori and Pre-School Teachers

10 Tuesday 7th April, 2009 The Island Features encourage constructive play. A “maths” area has scales for weighing and many Blubbery manipulatives for matching, sorting and counting. Nearby is the art/craft ‘researchers’ area with crayons, coloured pencils, scissors, glue, plasticine, magazines, drawing paper and scrap materials, lend fin to each neatly stored in plastic trays on open shelves. “A place for everything climate science and everything in its place”. A table TROLL RESEARCH STATION, Antarctica displays items collected from nature (AP) - and which can be examined with a Into the Antarctic enigma, the puzzle of a magnifying glass. Wall displays careful- place with too few researchers chasing too ly exhibit individual art achievements, many climate mysteries, slowly waddles the rather than twenty identical pictures. elephant seal. Posters of fruit, vegetables, vehicles, The fat-snouted pinniped, two ugly tons of parts of the body, trees and flowers blubber and roar, is plunging to its usual frigid offer visual stimulation.. By the win- depths these days in the service of climate dows are several pots for growing science, and of scientists’ budgets. plants and flowers, as well as a small “It would take years and millions and mil- fish tank. The pile of individual mats is lions of dollars for a research ship to do what for story or circle time. Every child has they’re doing,” Norwegian scientist Kim a laminated name card which is taken Holmen said of the instrument-equipped seals, from a box and placed on a wall chart whose long-distance swims and 1,000-foot when arriving in the morning.