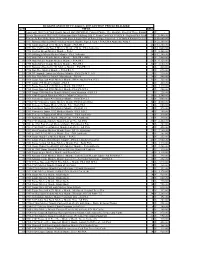

Overlooked Legend Award 2013 Nominees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2002 Auction Prices Realized

Fall 2002 Auction Prices Realized (Nov. 10, 2002) includes 15% buyer’s premium LOT# TITLE PRICE 1911 Sporting Life Honus Wagner Pastel Background PSA 8 1 NM/MT $6,785.00 2 1915 Cracker Jack #88 Christy Mathewson PSA 8 NM/MT $9,949.80 3 1933 Goudey #1 Benny Bengough PSA 8 NM/MT $12,329.15 4 1933 Goudey #181 Babe Ruth PSA 8 NM/MT $15,153.55 5 1934 Goudey #37 Lou Gehrig PSA 8 NM/MT $13,893.15 6 1934 Goudey #61 Lou Gehrig PSA 8 NM/MT $10,102.75 7 1938 Goudey #274 Joe DiMaggio PSA 8 NM/MT $11,003.20 8 1941 Play Ball #14 Ted Williams PSA 8 NM/MT $5,357.85 9 1941 Play Ball #71 Joe DiMaggio PSA 8 NM/MT $11,021.60 10 1948 Leaf #3 Babe Ruth PSA 8 NM/MT $5,299.20 11 1948 Leaf #76 Ted Williams PSA 8 NM/MT $5,920.20 12 1948 Leaf #79 Jackie Robinson $6,854.00 13 1955 Bowman #202 Mickey Mantle PSA 9 MINT $6,298.55 14 1956 Topps #33 Roberto Clemente PSA 9 MINT $5,969.65 15 1957 Topps #20 Hank Aaron PSA 9 MINT $2,964.70 16 1968 Topps #177 Mets Rookie Stars (Ryan) PSA 9 MINT $6,512.45 17 1961 Fleer #8 Wilt Chamberlain PSA 9 MINT $4,485.00 18 1968 Topps #22 Oscar Robertson PSA 8 NM/MT $3,183.20 19 1954 Topps #8 Gordie Howe PSA 9 MINT $7,225.45 20 1914 Cracker Jack Speaker PSA 8 NM/MT $4,210.15 21 1922 E120 American Caramel Walter Johnson PSA 8 NM/MT $2,443.75 22 1909 T 206 Sherry Magee (Magie) error SGC 20 $1,684.75 23 1934 Goudey #6 Dizzy Dean PSA 8 NM/MT $4,817.35 24 1915 Cracker Jack #10 John Mcinnis PSA 8 NM/MT $622.15 25 1915 Cracker Jack #21 Heinie Zimmerman PSA 8 NM/MT $622.15 26 1915 Cracker Jack #56 Clyde Milan PSA 8 NM/MT $465.75 27 1915 Cracker -

Doc Adams Base Ball

For Immediate Release: Contact: [email protected] Doc Adams’ “Laws of Baseball” Sells for $3.26 Million at Auction Connecticut Legislator and Bank President’s Document Gets Record Price A rare piece of baseball history sold on Sunday, April 24th for a price far exceeding what experts predicted. “The Laws of Baseball”, an 1857 document, was handwritten by Daniel Lucius “Doc” Adams. The “Laws of Baseball” was purchased for $3.26 million, making the item the highest-priced baseball document ever sold. SCP Auctions, which managed the sale, reported that the new owner wishes to remain anonymous. The manuscript details many of the fundamental aspects of baseball as written by Adams and illustrates the influence and contributions he made to the game. At the time the document was written, Adams was President of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club of New York City and chairman of the rules committee of the convention of New York and Brooklyn base ball clubs. In “The Laws of Baseball” Adams set the bases at 90 feet, established 9 players per side and 9 innings of play – all innovations at the time. This sale places the “Laws” as the third most expensive piece of sports history, behind a 1920 Yankees Babe Ruth jersey at $4.4 million and the James Naismith Rules of Basketball at $4.3 million. The Adams legacy has been garnering significant attention recently. SABR (Society for American Baseball Research) named Adams the 19th Century Overlooked Legend for 2014. His name was on the Pre-Integration Era Ballot for the Baseball Hall of Fame last year. -

The Jurisprudence of the Infield Fly Rule

Brooklyn Law School BrooklynWorks Faculty Scholarship Summer 2004 Taking Pop-Ups Seriously: The urJ isprudence of the Infield lF y Rule Neil B. Cohen Brooklyn Law School, [email protected] S. W. Waller Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/faculty Part of the Common Law Commons, Other Law Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation 82 Wash. U. L. Q. 453 (2004) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of BrooklynWorks. TAKING POP-UPS SERIOUSLY: THE JURISPRUDENCE OF THE INFIELD FLY RULE NEIL B. COHEN* SPENCER WEBER WALLER** In 1975, the University of Pennsylvania published a remarkable item. Rather than being deemed an article, note, or comment, it was classified as an "Aside." The item was of course, The Common Law Origins of the Infield Fly Rule.' This piece of legal scholarship was remarkable in numerous ways. First, it was published anonymously and the author's identity was not known publicly for decades. 2 Second, it was genuinely funny, perhaps one of the funniest pieces of true scholarship in a field dominated mostly by turgid prose and ineffective attempts at humor by way of cutesy titles or bad puns. Third, it was short and to the point' in a field in which a reader new to law reviews would assume that authors are paid by the word or footnote. Fourth, the article was learned and actually about something-how baseball's infield fly rule4 is consistent with, and an example of, the common law processes of rule creation and legal reasoning in the Anglo-American tradition. -

PDF of August 17 Results

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

Major League Baseball in Nineteenth–Century St. Louis

Before They Were Cardinals: Major League Baseball in Nineteenth–Century St. Louis Jon David Cash University of Missouri Press Before They Were Cardinals SportsandAmerican CultureSeries BruceClayton,Editor Before They Were Cardinals Major League Baseball in Nineteenth-Century St. Louis Jon David Cash University of Missouri Press Columbia and London Copyright © 2002 by The Curators of the University of Missouri University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65201 Printed and bound in the United States of America All rights reserved 54321 0605040302 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cash, Jon David. Before they were cardinals : major league baseball in nineteenth-century St. Louis. p. cm.—(Sports and American culture series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8262-1401-0 (alk. paper) 1. Baseball—Missouri—Saint Louis—History—19th century. I. Title: Major league baseball in nineteenth-century St. Louis. II. Title. III. Series. GV863.M82 S253 2002 796.357'09778'669034—dc21 2002024568 ⅜ϱ ™ This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984. Designer: Jennifer Cropp Typesetter: Bookcomp, Inc. Printer and binder: Thomson-Shore, Inc. Typeface: Adobe Caslon This book is dedicated to my family and friends who helped to make it a reality This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix Prologue: Fall Festival xi Introduction: Take Me Out to the Nineteenth-Century Ball Game 1 Part I The Rise and Fall of Major League Baseball in St. Louis, 1875–1877 1. St. Louis versus Chicago 9 2. “Champions of the West” 26 3. The Collapse of the Original Brown Stockings 38 Part II The Resurrection of Major League Baseball in St. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

Read an Excerpt

CONTENTS Foreword . xiii Preface . xix Part I • The Formation of the Team . 1 Wedding Bells . 3 Getting Started . 6 On the Other Side of South Mountain . 12 Waste Not, Want Not . 14 Understanding My Dad . 17 Understanding My Mom . 18 Understanding Mom and Dad—Together . 19 Dad’s “Other Love”—The United States Army . 25 Two More Army Forts and One Air Force Base . 30 Unfulfilled Dreams—A Soldier’s Plea Gets Denied . 34 The Emergence of a Football Coach . .. 37 1954 to 1964 . .40 Part II • Learning from Early Lessons—The Lehigh Years . 43 Taking a Shot—Coaching at Lehigh in the Early Years . 45 Entering the Fray—January 1965 . 50 A Challenge to the Culture . .. 54 Developing a Winning Culture on the Other Side of South Mountain . 58 “Trouble” on Willowbrook Drive . 67 The Dunlap Rules and Their Applications . 80 [ ii ] The 1966 Season—A Few Friends and a Bunch of Enemies . 80 The 1967 Season—Losing More than a Football Game . 92 An Uphill Fight . 95 Second Thoughts . 99 Don’t Mess with Marilyn Dunlap . 106 Living on a Shoestring . 110 Heartbreak Hill—The Fall 1968 Campaign . 114 Puberty—What in Blazes Is That? . 119 The Turning Point—The 1969 and 1970 Campaigns . 127 The 1969 Season . 127 The 1970 Season . 135 Respect and Gratitude . 144 When the Dunlap Rules Don’t Work—Fall 1971 . .. 146 Having a Really Good Wing Man (or Woman) . 156 The Little Things Took Care of the Big Things—Lehigh Football in 1971 . 165 An Entrepreneur Is Born . 168 Respect, Personal Accountability and the Gift of Tolerance— The Passage from a Kid to a Young Man . -

The Sports of Summer

Summer 2009 Summer East Chess Club 2009 Join others in playing chess all EDUCATION summer long! Every third Friday of Reading Challenge the month in June and July, the East Join in the 2009 Teen Summer Reading Chess Club will be meeting from CONNECTIONS 3:30 - 5 p.m. at East Library. Hope to Learning @ your library® Challenge. Read books and get prizes ranging see you there! For more information, from Sky Sox tickets and bowling passes to contact [email protected]. books, journals, and T-shirts! Sports Books for Teens The Sports of Summer Fiction Summer is here! As the days grow longer, the kids are out in full force: running, kicking, passing, Enter to win the Beanball by Gene Fehler catching; all enjoying the fresh air and vigorous workouts of being part of the game… under the banner grand prizes of Game by Walter Dean Myers of youth sports. a BMX bike, My 13th Season by Kristi Roberts Maverick Mania by Sigmund Brouwer Youth sports can be an invaluable aspect in learning life lessons. Foundational character skateboard, Love, Football, and Other Contact Sports by Alden R. Carter building principles can be learned through teamwork, perseverance, ability to deal with adversity, and $100 Visa sportsmanship, and the value of hard work. What could be a better environment for such important Nonfi ction training, while engaging in active physically demanding skills? gift cards! The Comprehensive Guide to Careers Visit your local in Sports by Glenn M. Wong There are many summer sports to choose from: baseball, Why a Curveball Curves : The PPLD branch Incredible Science of Sports by Frank soccer, lacrosse, tennis, and many more are offered through Vizard a variety of organized team clubs, the YMCA, and the city/ to learn more Career Ideas for Kids Who Like Sports county parks and recreational entities. -

Deaf Baseball Players in Kansas and Kansas City, 1878–1911 Mark E

Fort Hays State University FHSU Scholars Repository Monographs 2019 Deaf Baseball Players in Kansas and Kansas City, 1878–1911 Mark E. Eberle Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.fhsu.edu/all_monographs Part of the History Commons Deaf Baseball Players in Kansas and Kansas City, 1878–1911 Mark E. Eberle Deaf Baseball Players in Kansas and Kansas City, 1878–1911 © 2019 by Mark E. Eberle Cover image: Kansas State School for the Deaf baseball teams (1894) and Kansas City Silents (1906). From the archives of the Kansas State School for the Deaf, Olathe, Kansas. Recommended citation: Eberle, Mark E. 2019. Deaf Baseball Players in Kansas and Kansas City, 1878–1911. Fort Hays State University, Hays, Kansas. 25 pages. Deaf Baseball Players in Kansas and Kansas City, 1878–1911 Mark E. Eberle Edward Dundon (1859–1893) played baseball in 1883 and 1884 for the Columbus Buckeyes of the American Association, a major league at the time. William Hoy (1862– 1961) was a major league outfielder from 1888 through 1902 for teams in the National League, Players League, American Association, and American League. Luther Taylor (1875–1958) pitched in the major leagues for the New York Giants (now the San Francisco Giants) from 1900 through 1908, and he played briefly for the Cleveland Bronchos (now the Cleveland Indians) in 1902. Monroe Ingram (1865?–1944) was a black ballplayer, so he was limited to pitching for an integrated minor league team in Emporia, Kansas in 1896 and 1897. In addition to having professional baseball careers in common, all four men were deaf. -

Baseball Cyclopedia

' Class J^V gG3 Book . L 3 - CoKyiigtit]^?-LLO ^ CORfRIGHT DEPOSIT. The Baseball Cyclopedia By ERNEST J. LANIGAN Price 75c. PUBLISHED BY THE BASEBALL MAGAZINE COMPANY 70 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK CITY BALL PLAYER ART POSTERS FREE WITH A 1 YEAR SUBSCRIPTION TO BASEBALL MAGAZINE Handsome Posters in Sepia Brown on Coated Stock P 1% Pp Any 6 Posters with one Yearly Subscription at r KtlL $2.00 (Canada $2.00, Foreign $2.50) if order is sent DiRECT TO OUR OFFICE Group Posters 1921 ''GIANTS," 1921 ''YANKEES" and 1921 PITTSBURGH "PIRATES" 1320 CLEVELAND ''INDIANS'' 1920 BROOKLYN TEAM 1919 CINCINNATI ''REDS" AND "WHITE SOX'' 1917 WHITE SOX—GIANTS 1916 RED SOX—BROOKLYN—PHILLIES 1915 BRAVES-ST. LOUIS (N) CUBS-CINCINNATI—YANKEES- DETROIT—CLEVELAND—ST. LOUIS (A)—CHI. FEDS. INDIVIDUAL POSTERS of the following—25c Each, 6 for 50c, or 12 for $1.00 ALEXANDER CDVELESKIE HERZOG MARANVILLE ROBERTSON SPEAKER BAGBY CRAWFORD HOOPER MARQUARD ROUSH TYLER BAKER DAUBERT HORNSBY MAHY RUCKER VAUGHN BANCROFT DOUGLAS HOYT MAYS RUDOLPH VEACH BARRY DOYLE JAMES McGRAW RUETHER WAGNER BENDER ELLER JENNINGS MgINNIS RUSSILL WAMBSGANSS BURNS EVERS JOHNSON McNALLY RUTH WARD BUSH FABER JONES BOB MEUSEL SCHALK WHEAT CAREY FLETCHER KAUFF "IRISH" MEUSEL SCHAN6 ROSS YOUNG CHANCE FRISCH KELLY MEYERS SCHMIDT CHENEY GARDNER KERR MORAN SCHUPP COBB GOWDY LAJOIE "HY" MYERS SISLER COLLINS GRIMES LEWIS NEHF ELMER SMITH CONNOLLY GROH MACK S. O'NEILL "SHERRY" SMITH COOPER HEILMANN MAILS PLANK SNYDER COUPON BASEBALL MAGAZINE CO., 70 Fifth Ave., New York Gentlemen:—Enclosed is $2.00 (Canadian $2.00, Foreign $2.50) for 1 year's subscription to the BASEBALL MAGAZINE. -

The Irish in Baseball ALSO by DAVID L

The Irish in Baseball ALSO BY DAVID L. FLEITZ AND FROM MCFARLAND Shoeless: The Life and Times of Joe Jackson (Large Print) (2008) [2001] More Ghosts in the Gallery: Another Sixteen Little-Known Greats at Cooperstown (2007) Cap Anson: The Grand Old Man of Baseball (2005) Ghosts in the Gallery at Cooperstown: Sixteen Little-Known Members of the Hall of Fame (2004) Louis Sockalexis: The First Cleveland Indian (2002) Shoeless: The Life and Times of Joe Jackson (2001) The Irish in Baseball An Early History DAVID L. FLEITZ McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Fleitz, David L., 1955– The Irish in baseball : an early history / David L. Fleitz. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-3419-0 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Baseball—United States—History—19th century. 2. Irish American baseball players—History—19th century. 3. Irish Americans—History—19th century. 4. Ireland—Emigration and immigration—History—19th century. 5. United States—Emigration and immigration—History—19th century. I. Title. GV863.A1F63 2009 796.357'640973—dc22 2009001305 British Library cataloguing data are available ©2009 David L. Fleitz. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: (left to right) Willie Keeler, Hughey Jennings, groundskeeper Joe Murphy, Joe Kelley and John McGraw of the Baltimore Orioles (Sports Legends Museum, Baltimore, Maryland) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Je›erson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Acknowledgments I would like to thank a few people and organizations that helped make this book possible. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig