A Case Study of M-Ward in Mumbai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BHABHA ATOMIC RESEARCH CENTRE Monthly Report On

BHABHA ATOMIC RESEARCH CENTRE Monthly Report on Implementation of RTI for the period 01.10.2011 to 31.12.2011 Name of the Unit: BARC, Trombay, Mumbai Applications received / Processed during the period: Oct to Dec. 2011. Sr. Request Party Subject Date of ** Mode of Action taken Remarks No. No. (Brief description of query) receipt Amount Payment Recd. (`) 1 09-889 Dr. Vishvas M. Kulkarni, Plant Cell Inf.on applications submitted to the 02.9.11 - - Information Culture Technology Section, Institutional Bio-Safety Committee provided on NABTD, BARC, Mumbai - 85 of BARC. 12.10.2011. 2 09-897 Shri V.R.G. Prakash, 1/75, Raja Radiation effect on installation of 14.9.11 - - Information Industrial Estate P.K. Road, mobile ground station & antenna on provided on Mulund, Mumbai-400080. terrace. 11.10.2011. 3 09-899 Shri Ashok Kumar, SO/D, CHSS facility for dependents 15.9.11 - - Information HUL&ESS, RLG Bldg.,BARC, provided on Trombay, Mumbai-400085. 10.10.2011. 4 09-900 Shri Sunil K. Sahu, SO/C, TPD, 3- Criteria for availing CHSS. 15..9.11 - - Information 10-H, Mod.Labs, BARC, Trombay, provided on Mumbai-400085. 14.10.2011. 5 09-902 Shri N.M. Gandhi, RB&HSD/BMG, Action taken on representation to 15..9.11 - - Information BARC, Trombay, Mumbai- Director, BARC. provided on 400085. 07.10.2011. 6 09-904 Shri Suresh G.Gholap, Bank account details of BARC 19..9.11 -* - Information *Fee in the form of Court Spl.Recovery employee. provided on Fee Stamp, not Officer,Yashomandir Co- 17.10.2011. -

Maharashtra State Boatd of Sec & H.Sec Education Pune

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 1 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2020 Division : MUMBAI Candidates passed School No. Name of the School Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 16.01.001 SAKHARAM SHETH VIDYALAYA, KALYAN,THANE 185 185 22 57 52 29 160 86.48 27210508002 16.01.002 VIDYANIKETAN,PAL PYUJO MANPADA, DOMBIVLI-E, THANE 226 226 198 28 0 0 226 100.00 27210507603 16.01.003 ST.TERESA CONVENT 175 175 132 41 2 0 175 100.00 27210507403 H.SCHOOL,KOLEGAON,DOMBIVLI,THANE 16.01.004 VIVIDLAXI VIDYA, GOLAVALI, 46 46 2 7 13 11 33 71.73 27210508504 DOMBIVLI-E,KALYAN,THANE 16.01.005 SHANKESHWAR MADHYAMIK VID.DOMBIVALI,KALYAN, THANE 33 33 11 11 11 0 33 100.00 27210507115 16.01.006 RAYATE VIBHAG HIGH SCHOOL, RAYATE, KALYAN, THANE 151 151 37 60 36 10 143 94.70 27210501802 16.01.007 SHRI SAI KRUPA LATE.M.S.PISAL VID.JAMBHUL,KULGAON 30 30 12 9 2 6 29 96.66 27210504702 16.01.008 MARALESHWAR VIDYALAYA, MHARAL, KALYAN, DIST.THANE 152 152 56 48 39 4 147 96.71 27210506307 16.01.009 JAGRUTI VIDYALAYA, DAHAGOAN VAVHOLI,KALYAN,THANE 68 68 20 26 20 1 67 98.52 27210500502 16.01.010 MADHYAMIK VIDYALAYA, KUNDE MAMNOLI, KALYAN, THANE 53 53 14 29 9 1 53 100.00 27210505802 16.01.011 SMT.G.L.BELKADE MADHYA.VIDYALAYA,KHADAVALI,THANE 37 36 2 9 13 5 29 80.55 27210503705 16.01.012 GANGA GORJESHWER VIDYA MANDIR, FALEGAON, KALYAN 45 45 12 14 16 3 45 100.00 27210503403 16.01.013 KAKADPADA VIBHAG VIDYALAYA, VEHALE, KALYAN, THANE 50 50 17 13 -

380 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

380 bus time schedule & line map 380 Amrut Nagar (Vikhroli-W) View In Website Mode The 380 bus line (Amrut Nagar (Vikhroli-W)) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Amrut Nagar (Vikhroli-W): 5:12 AM - 5:52 AM (2) Anushakti Nagar: 8:18 AM - 8:10 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 380 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 380 bus arriving. Direction: Amrut Nagar (Vikhroli-W) 380 bus Time Schedule 44 stops Amrut Nagar (Vikhroli-W) Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 5:12 AM - 5:52 AM Monday 5:12 AM - 5:52 AM Anushakti Nagar V.N. Purav Marg, Mumbai Tuesday 5:12 AM - 5:52 AM Agarwadi (Mankhurd) Wednesday 5:12 AM - 5:52 AM V.N. Purav Marg, Mumbai Thursday 5:12 AM - 5:52 AM Mankhurd Railway Station (N) Friday 5:12 AM - 5:52 AM Maharashtra Nagar Saturday 5:12 AM - 5:52 AM Mohite Patil Nagar Railway Colony 380 bus Info Annabhau Sathe Ngr. Direction: Amrut Nagar (Vikhroli-W) Stops: 44 B.M.C.Compost Plant Trip Duration: 33 min Line Summary: Anushakti Nagar, Agarwadi Bainganwadi (Mankhurd), Mankhurd Railway Station (N), Maharashtra Nagar, Mohite Patil Nagar, Railway Colony, Annabhau Sathe Ngr., B.M.C.Compost Plant, Bainganwadi Bainganwadi, Bainganwadi, 600 Tenament Gate, Tata Nagar / Sambhaji Nagar, Deonar Municipal Cly., 600 Tenament Gate Deonar Police Station, New Gautam Ngr., Ashish Nagar, Narayan Guru High School, Shivsena O∆ce, Tata Nagar / Sambhaji Nagar Ambedkar Nagar, Amar Mahal, Amar Mahal, Sahakar Talkies, Pestam Sagar / Glass Factory, Sommaiya Deonar Municipal Cly. -

Thursday, July 11, 2019 / Ashadha 20, 1941 (Saka) ______

LOK SABHA ___ SYNOPSIS OF DEBATES* (Proceedings other than Questions & Answers) ______ Thursday, July 11, 2019 / Ashadha 20, 1941 (Saka) ______ SUBMISSION BY MEMBERS Re: Farmers facing severe distress in Kerala. THE MINISTER OF DEFENCE (SHRI RAJ NATH SINGH) responding to the issue raised by several hon. Members, said: It is not that the farmers have been pushed to the pitiable condition over the past four to five years alone. The miserable condition of the farmers is largely attributed to those who have been in power for long. I, however, want to place on record that our Government has been making every effort to double the farmers' income. We have enhanced the Minimum Support Price and did take a decision to provide an amount of Rs.6000/- to each and every farmer under Kisan Maan Dhan Yojana irrespective of the parcel of land under his possession and have brought it into force. This * Hon. Members may kindly let us know immediately the choice of language (Hindi or English) for obtaining Synopsis of Lok Sabha Debates. initiative has led to increase in farmers' income by 20 to 25 per cent. The incidence of farmers' suicide has come down during the last five years. _____ *MATTERS UNDER RULE 377 1. SHRI JUGAL KISHORE SHARMA laid a statement regarding need to establish Kendriya Vidyalayas in Jammu parliamentary constituency, J&K. 2. DR. SANJAY JAISWAL laid a statement regarding need to set up extension centre of Mahatma Gandhi Central University, Motihari (Bihar) at Bettiah in West Champaran district of the State. 3. SHRI JAGDAMBIKA PAL laid a statement regarding need to include Bhojpuri language in Eighth Schedule to the Constitution. -

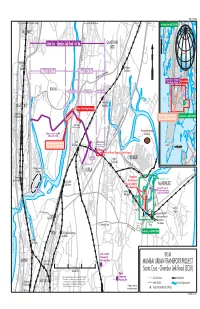

Chembur Link Road (SCLR) Matunga to Mumbai Rail Station This Map Was Produced by the Map Design Unit of the World Bank

IBRD 33539R To Jogeswari-Virkhroli Link Road / Borivali To Jogeswari-Virkhroli Link Road To Thane To Thane For Detail, See IBRD 33538R VILE PARLE ek re GHATKOPAR C i r Santa Cruz - Chembur Link Road: 6.4 km o n a SATIS M Mumbai THANE (Kurla-Andhai Road) Vile Parle ek re S. Mathuradas Vasanji Marg C Rail alad Station Ghatkopar M Y Rail Station N A Phase II: 3.0 km Phase I: 3.4 km TER SW S ES A E PR X Lal Bahadur Shastri Marg WESTERN EXPRESSWAY E Santa Cruz - Chembur Link Road: 6.4 km Area of Map KALINA Section 1: 1.25 km Section 2: 1.55 km Section 3: .6 km ARABIAN Swami Vivekananda Marg SEA Vidya Vihar Thane Creek SANTA CRUZ Rail Station Area of Gazi Nagar Request Mahim Bay Santa Cruz Rail Station Area of Shopkeepers' Request For Detail, See IBRD 33540R For Detail, See IBRD 33314R MIG Colony* (Middle Income Group) Central Railway Deonar Dumping 500m west of river and Ground 200m south of SCLR Eastern Expressway R. Chemburkar Marg Area of Shopkeepers' Request Kurla MHADA Colony* CHURCHGATE CST (Maharashtra Housing MUMBAI 012345 For Detail, See IBRD 33314R Rail Station and Area Development Authority) KILOMETERS Western Expressway Area of Bharathi Nagar Association Request S.G. Barve Marg (East) Gha Uran Section 2 Chembur tko CHEMBUR Rail Station parM ankh urdLink Bandra-Kurla R Mithi River oad To Vashi Complex KURLA nar Nala Deo Permanent Bandra Coastal Regulation Zones Rail Station Chuna Batti Resettlement Rail Station Housing Complex MANKHURD at Mankhurd Occupied Permanent MMRDA Resettlement Housing Offices Govandi Complex at Mankhurd Rail Station Deonar Village Road Mandala Deonarpada l anve Village P Integrated Bus Rail Sion Agarwadi Interchange Terminal Rail Station Mankhurd Mankhurd Correction ombay Rail Station R. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS, -

Annual Report : 2016 - 2017

ANNUAL REPORT : 2016 - 2017 Rotary Club of Bombay Midtown facilitated a educational visit to NASEOH for 28 students from Germany under Youth Exchange Programme. Field Placement of students : Name of the Institute Department Number of students Tata Institute of Social Sciences Social Work 2 Tata Institute of Social Sciences Centre for Life Long learning 2 SNDT University Social Work 2 Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth Social Work 6 Swami Vivekanand College, Chembur N.S.S 65 ST. Xaviers' College , Mumbai Social Involvement Program 5 Don Bosco College of Management MBA 4 S.I.E.S College of Management MBA 6 APPRECIATION AND AWARDS NASEOH, during Diwali celebration recognizes Best Child and Best Trainee from each unit whose over all progress has been outstanding. This year the following students received the Best Student appreciations of the year. Name Unit 1. Mst. Aditya Pandya - Falguni Learning Centre (special group) 2. Mst. Vinayak Sangishetty - Falguni Learning Centre (Functional group) 3. Mr. Rohit Dharne - Tailoring 4. Mr. Parikshit Karve - Computer 5 Mr. Akshay Bhor - Bakery & Confectionery 6. Ms. Madhavi Asware - Assembly 7. Mr. Vishal Hande - Ceramic 8. Mr. Mohammed Shafique Shaikh - Welding & Fabrication 9. Mr. Pandurang Pai - Garden 10. Mr. Mohammed Zaid Kasam - Aids & Appliances Felicitation Program As of every year, this year also Rotary Club of Bombay Mid Town felicitated following two computer trainees, who stood 1st in their respective batches during 2015-16, with Cash Awards. 1. Ms. Sneha Dhuri - July'2015 batch 2. Ms. Mahisha Agvane - January'2016 batch AWARENESS & ADVOCACY Open House NASEOH organized various talks for creating awareness among trainees and parents on varied topics during the year as detailed below : 1) Importance of Independence day 2) Different types of BMC and Government schemes for disabled 3) Awareness about Hepatitis B 4) Traffic rules 5) Personal Hygiene 6) Ill-effect of tobacco chewing Distribution of Clothes With initiative and donation from Mr. -

Version 1.0 List No. 1 - Vtps to Whom Not a Single TBN Is Allotted in Any Government Funded Scheme (As on 28.01.2019)

Version 1.0 List No. 1 - VTPs to Whom Not a single TBN is allotted in any Government Funded Scheme (as on 28.01.2019) Sr. No. District VTP ID VTP Name Date of Empanelment Sector Courses Address Mobile No. Email ID BASIC AUTOMOTIVE SERVICING 2 WHEELER 3 WHEELER BASIC AUTOMOTIVE SERVICING 4 WHEELER REPAIR AND OVERHAULING OF 2 WHEELERS AND 3 WHEELER ELECTRICIAN DOMESTIC ELECTRICIAN DOMESTIC ELECTRICIAN DOMESTIC ELECTRICAL WINDER ELECTRICAL WINDER AUTOMOTIVE REPAIR ARC AND GAS WELDER ELECTRICAL ARC AND GAS WELDER SHIRDI SAI RURAL INSTITUTE ITC-3272690032 , FABRICATION At - Rahata Tal - Rahata Rahata 1 Ahmadnagar 2726A00402A001 07-11-2015 00:00 ARC AND GAS WELDER 7588169832 [email protected] AHMEDNAGAR GARMENT MAKING Ahmednagar TIG WELDER INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGY CO2 WELDER REFRIGERATION AND AIR CONDITIONING PIPE WELDER (TIG AND MMAW) HAND EMBROIDER ZIG-ZAG MACHINE EMBROIDERY ACCOUNTS ASSISTANT USING TALLY DTP AND PRINT PUBLISHING ASSISTANT COMPUTER HARDWARE ASSISTANT REFRIGERATION/ AIR CONDITIONING/ VENTILATION MECHANIC ( ELECTRICAL CONTROL) ACCOUNTING ACCOUNTS ASSISTANT USING TALLY Regd.23 Kaustubha Sonanagar Savedi DTP AND PRINT PUBLISHING ASSISTANT MAHARASHTRA TANTRIK SHIKSHAN MANDAL-3272694044 , BANKING AND ACCOUNTING Road Ahmednagar 2 Ahmadnagar 2726A00098A006 07-11-2015 00:00 WEB DESIGNING AND PUBLISHING ASSISTANT 9822147888 [email protected] SHEVGAON INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGY Center:Oppt.New Arts College, Miri WEB DESIGNING AND PUBLISHING ASSISTANT Road, Shevgaon, Ahmednagar COMPUTER HARDWARE -

"Proposed Municipal Maternity Home and General Hospital"

FORM – I [Vide Notification dated 1st December, 2009] For Proposed Project "Proposed Municipal Maternity Home and General Hospital" At Amenity plot bearing C.T.S. No. 2B/4B (Part) of village Mankhurd, Taluka Kurla B.S.D. & situated at Agarwadi Road, Tatanagar, Mankhurd, , Mumbai, Maharashtra Of Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA) Being Developed by M/S. Matrubhoomi Granites Pvt. Ltd. Prepared by MITCON Consultancy & Engineering Services Ltd. Behind DIC Office, Agri College Campus, Shivajinagar, Pune - 411 005, Maharashtra (INDIA), Tele No.: 020-25530308/09, Fax No.: 020-25530307 The Project “Municipal Maternity Home and General Hospital” of MMRDA being developed by Matrubhoomi Granites Pvt. Ltd at Amenity plot bearing C.T.S. No. 2B/4B (Part) of village Mankhurd, Taluka Kurla B.S.D. & situated at Agarwadi Road, Tatanagar, Mankhurd, Mumbai, Maharashtra (I) BASIC INFORMATION Sr. Item Details No. 1. Name of the project/s “Proposed Municipal Maternity Home and General Hospital” 2. S. No. in the schedule The Project falls under category B2 of project activity number 8(a) as per MOEF notification, 2006 3. Proposed capacity/area/length/tonnage to • Total Plot Area: 7,913.80 m2 handled/command area/lease area/number • Deduction: 1,187.07 m2 wells to be drilled • Net Balance Plot Area: 6726.73 m2 • Total FSI Area: 26,872.55 m2 • Total Non FSI Area : 9,128.25 m2 • Total Construction BUA: 36,000.80 m2 4. New/Expansion/Modernization New Project 5. Existing Capacity/Area etc. As per old LOI received construction area of 18,014.31 m2 is constructed on site. -

Bus-Shelter-Advertising.Pdf

1 ONE STOP MARKETING 2 What Are You Looking For? AIRLINE/AIRPORT CINEMA DIGITAL NEWSPAPER RADIO TELEVISION MAGAZINE SERVICES OUTDOOR NON TRADITIONAL 3 Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Powai, Mumbai Suresh Nagar, Mumbai Near L&T, Powai Garden, Powai Military Road Juhu-Versova Link Road ,Bharat Nagar/Petrol Pump Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Juhu, Mumbai VN Purav Marg, Mumbai Juhu S.Parulekar Marg, Traffic Towrds Juhu Bus Station Marathi Vidnyan Parishad, V. N. Purav Road, Chunabhatti Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Andheri East, Mumbai Andheri East, Mumbai International Airport Road, Sahar Road, Ambassador Outside Techno Mall, Jogeshwari Link Road, Behram Hotel Bagh 4 Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Lohar Chawl, Mumbai Lad Wadi, Mumbai Kalbadevi Road ,Princess Street 2 Kalbadevi Road ,Princess Street 1 Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Savarkar Nagar, Mumbai Mahim Nature park, Mumbai Near L&T, Powai Garden, Powai Military Road Dharavi Depot, Dumping Road, Dharavi Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Antop Hill, Mumbai Bharat Nagar, Mumbai Antop Hill, Shaikh Misri Road, Antop Hill Juhu-Versova Link Road ,Bharat Nagar/Petrol Pump 5 Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Bus Shelter @ INR 35,000/- Per Month Wadala, Mumbai Kurla East, Mumbai Wadala Station, Kidwai Marg, Wadala S.T. Depot (Kurla East), S.T. -

J J P B I English A188115 A188271 157 Girl's School 209 Dadabhai Nauroji Road Fort,Mumbai Pin Code :- 400001 Phone : 22612577 Additional Seatno

For HSC Board March Seating Plan/Centers CLICK HERE MAHARASHTRA STATE BOARD OF SECONDARY AND HIGHER SECONDARY EDUCATION, MUMBAI DIVISIONAL BOARD ,VASHI, NAVI MUMBAI 400 703. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SEATING ARRANGEMENT OF MARCH - 2014 S.S.C. EXAMINATION PAGE NO: 1 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NAME OF THE CENTRE : -MUMBAI CST (FORT) CENTRE NO :- 2001 FROM :- A187165 TO A188271 REGISTER NO OF CANDIDATES :- 1107 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SR SCHOOL NAME OF THE PLACE NUMBER OF CANDIDATES NO IND NO TELEPHONE NO FROM TO TOTAL -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 3101004 SIR J J FORT BOYS HIGH SCHOOL A187165 A187364 200 209 DR DADABHAI NAUROJI ROAD FORT MAIN CENTRE MUMBAI PIN CODE :- 400001 PHONE : 22626155 ADDITIONAL SEATNO:- 2 3101011 BHARDA NEW HIGH SCHOOL A187365 A187764 400 HAZARIMAL SOMANI MARG FORT MUMBAI PIN CODE :- 400001 PHONE : 22072349 ADDITIONAL SEATNO:- 3 3101033 ST ANNIES HIGH SCHOOL A187765 A188114 350 MADAM KAMA ROAD FORT MUMBAI PIN CODE :- 400001 PHONE : 22020733 ADDITIONAL SEATNO:- 4 3101005 SIRwww.Exam2014.in J J P B I ENGLISH A188115 A188271 157 GIRL'S SCHOOL 209 DADABHAI NAUROJI ROAD FORT,MUMBAI PIN CODE :- 400001 PHONE : 22612577 ADDITIONAL SEATNO:- For HSC Board March Seating Plan/Centers CLICK HERE -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SEATING ARRANGEMENT OF MARCH - 2014 -

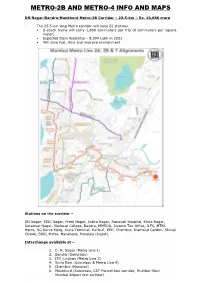

Metro-2B and Metro-4 Info and Maps

METRO-2B AND METRO-4 INFO AND MAPS DN Nagar-Bandra-Mankhurd Metro-2B Corridor – 23.5-km – Rs. 10,986 crore · The 23.5-km long Metro corridor will have 22 stations • 6-coach trains will carry 1,800 commuters per trip (8 commuters per square meter) • Expected Daily Ridership – 8.099 Lakh in 2021 • Will save fuel, time and improve environment Stations on the corridor – DN Nagar, ESIC Nagar, Prem Nagar, Indira Nagar, Nanavati Hospital, Khira Nagar, Saraswat Nagar, National College, Bandra, MMRDA, Income Tax Office, ILFS, MTNL Metro, SG Barve Marg, Kurla Terminal, Kurla-E, EEH, Chembur, Diamond Garden, Shivaji Chowk, BSNL Metro, Mankhurd, Mandala (Depot). Interchange available at – 1. D. N. Nagar (Metro Line 1) 2. Bandra (Suburban) 3. ITO junction (Metro Line 3) 4. Kurla East (Suburban & Metro Line 4) 5. Chembur (Monorail) 6. Mankhurd (Suburban, CST-Panvel fast corridor, Mumbai–Navi Mumbai Airport fast corridor) Wadala-Ghatkopar-Thane -Kasarvadavli Metro-4 corridor – 32-km – Rs. 14,549 crore • The 32.32-km long Metro corridor will have 32 stations • 6-coach trains will carry 1,800 commuters per trip (8 commuters per square meter) • Expected Daily Ridership – 8.7 Lakh in 2021-22 • Will save fuel, time and improve environment Stations on the Corridor – Wadala Depot, Bhakti Park Metro, Anik Nagar Bus Depot, Suman Nagar, Siddharth Colony, Amar Mahal Junction, Garodia Nagar, Pant Nagar, Laxmi Nagar, Shreyas Cinema, Godrej Company, Vikhroli Metro, Surya Nagar, Gandhi Nagar, Naval Housing, Bhandup Mahapalika, Bhandup Metro, Shangrila, Sonapur, Mulund Fire Sta tion, Mulund Naka, Teen Haath Naka (Thane), RTO Thane, Mahapalika Marg, Cadbury Junction, Majiwada, Kapurbawdi, Manpada, Tikuji -ni-wadi, Dongri Pada, Vijay Garden, Kasarvadavali with car depot at Owale .