Snakes Discussion Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines for Keeping Venomous Snakes in the NT

GUIDELINES FOR KEEPING VENOMOUS SNAKES IN THE NT Venomous snakes are potentially dangerous to humans, and for this reason extreme caution must be exercised when keeping or handling them in captivity. Prospective venomous snake owners should be well informed about the needs and requirements for keeping these animals in captivity. Permits The keeping of protected wildlife in the Northern Territory is regulated by a permit system under the Territory Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 2006 (TPWC Act). Conditions are included on permits, and the Parks and Wildlife Commission of the Northern Territory (“PWCNT”) may issue infringement notices or cancel permits if conditions are breached. A Permit to Keep Protected Wildlife enables people to legally possess native vertebrate animals in captivity in the Northern Territory. The permit system assists the PWCNT to monitor wildlife kept in captivity and to detect any illegal activities associated with the keeping of, and trade in, native wildlife. Venomous snakes are protected throughout the Northern Territory and may not be removed from the wild without the appropriate licences and permits. People are required to hold a Keep Permit (Category 1–3) to legally keep venomous snakes in the Northern Territory. Premises will be inspected by PWCNT staff to evaluate their suitability prior to any Keep Permit (Category 1– 3) being granted. Approvals may also be required from local councils, the Northern Territory Planning Authority, and the Department of Health and Community Services. Consignment of venomous snakes between the Northern Territory and other States and Territories can only be undertaken with an appropriate import / export permit. There are three categories of venomous snake permitted to be kept in captivity in the Northern Territory: Keep Permit (Category 1) – Mildly Dangerous Venomous Keep Permit (Category 2) – Dangerous Venomous Keep Permit (Category 3) – Highly Dangerous Venomous Venomous snakes must be obtained from a legal source (i.e. -

Draft Animal Keepers Species List

Revised NSW Native Animal Keepers’ Species List Draft © 2017 State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage With the exception of photographs, the State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. The Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) has compiled this report in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. OEH shall not be liable for any damage which may occur to any person or organisation taking action or not on the basis of this publication. Readers should seek appropriate advice when applying the information to their specific needs. All content in this publication is owned by OEH and is protected by Crown Copyright, unless credited otherwise. It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0), subject to the exemptions contained in the licence. The legal code for the licence is available at Creative Commons. OEH asserts the right to be attributed as author of the original material in the following manner: © State of New South Wales and Office of Environment and Heritage 2017. Published by: Office of Environment and Heritage 59 Goulburn Street, Sydney NSW 2000 PO Box A290, -

Berriquin LWMP Wildlife

Berriquin Wildlife Murray Land & Water Management Plan Wildlife Survey 2005-2006 Matthew Herring David Webb Michael Pisasale INTRODUCTION Why do a wildlife survey? 106 farms and were surveyed One of the great things about between June 2005 and March living in rural Australia is all the 2006. They incorporated a range wildlife that we share the land- of vegetation types (e.g. Black scape with. Historically, humans Box Woodland) as well as reveg- have impacted on the survival of etation on previously cleared many native plants and animals. land and constructed wetlands. Fortunately, there is a grow- Methods used to survey wildlife ing commitment in the country included: to wildlife conservation on the farm. As we improve our knowl- - Bird surveys edge and understanding of the - Log rolling for reptiles and local landscape and the animals frogs and plants that live in it we will - Spotlighting for mammals, rep be in a much better position to tiles and nocturnal birds conserve and enhance our natu- - Elliot traps for small mammals ral heritage for future genera- and reptiles tions. - Pitfall trapping for reptiles and frogs This wildlife survey was an ini- - Harp traps for bats tiative of the Berriquin Land & - Using the “Anabat” to record Water Management Plan (LWMP) bat calls M.Herring Working Group and is the largest - Call broadcasting to attract Wildlife expert Adam Bester and most extensive ever un- birds with 11 Little Forest Bats, one dertaken in the area. Berriquin of Berriquin’s most abundant was one of four LWMP areas that Other targeted methods were mammals. -

Creatures That Can Kill You 5

AROUND THE WORLD PREVIEWITH WSNAKES Preview Snakes slither through nearly every country on Earth. Most snakes are harmless, but some of them are are anything but. In this chapter, we will travel from India to Australia to Africa. The scariest, the deadliest, and the most feared snakes—they’re all here! 1 Around The World With Snakes AROUNDIn a rice THEfield in WORLD India, a young WITH worker namedSNAKES Abhay stepped carefully around the plants he tended. As always, Abhay listened for any quick rustling through the leaves or, worse yet, In a ricea sudden field hissing. in India, But as thea youngsky began workergrowing named Abhaydark stepped with rain carefully clouds, Abhay around became the careless plants he in his hurry to finish his job. He moved quickly tended.through As always, some tallerAbhay plants listened that blocked for any his quick rustlingview through of the ground. the leaves or, worse yet, a sudden hissing. But as the sky began growing dark with rain clouds, Abhay became careless in his hurry to finish his job. He moved quickly through some taller plants that blocked his view of the ground. Then, just at the edge of the field, Abhay felt something very strange. It was as if a thick cord of rope had been yanked beneath his left foot. 3 4 MARIE NOBLE In that same instant, Abhay saw a flash of brown and gold rise up before him—the dreaded Indian cobra. It was not the first time he had seen this terrifying snake. From the time he was a young child, Abhay had often seen these 6- to 10-foot snakes slithering through the village where he lived. -

Taxonomy of the Genus Pseudonaja (Reptilia: Elapidae) in Australia

AUSTRALIAN BIODIVERSITY RECORD ________________________________________________________ 2002 (No 7) ISSN 1325-2992 March, 2002 ________________________________________________________ Taxonomy of the Genus Pseudonaja (Reptilia: Elapidae) in Australia. by Richard W. Wells “Shiralee”, Major West Road, Cowra, New South Wales, Australia The clear morphological differences that exist within the genus as previously considered strongly indicate that it is a polyphyletic assemblage. Accordingly, I have taken the step of formally proposing the fragmentation of Pseudonaja. In this work I have decided to restrict the genus Pseudonaja to the Pseudonaja nuchalis complex. Additionally, I herein formally resurrect from synonymy the generic name Euprepiosoma Fitzinger, 1860 for the textilis group of species, erect a new generic name (Placidaserpens gen. nov.) for the snakes previously regarded as Pseudonaja guttata, erect a new generic name (Notopseudonaja gen. nov.) for the group of species previously regarded as the Pseudonaja modesta complex, and erect a new generic name (Dugitophis gen. nov.) for snakes previously regarded as the Pseudonaja affinis complex. Genus Pseudonaja Gunther, 1858 The Pseudonaja nuchalis Complex It is usually reported that Pseudonaja nuchalis occurs across most of northern, central and western Australia, ranging from Cape York Peninsula, in the north-east, through western, southern and south-eastern Queensland, far western New South Wales, north-western Victoria, and most of South Australia, Northern Territory and Western Australia. However, this distribution pattern is now known to actually represents several different species all regarded by most authorities for convenience as the single highly variable species, 'Pseudonaja nuchalis'. As usually defined, this actually is a highly variable and therefore confusing group of species to identify and it is not all surprising that there has been difficulty in breaking up the group. -

Proteomic and Genomic Characterisation of Venom Proteins from Oxyuranus Species

This file is part of the following reference: Welton, Ronelle Ellen (2005) Proteomic and genomic characterisation of venom proteins from Oxyuranus species. PhD thesis, James Cook University Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/11938 Chapter 1 Introduction and literature review Chapter 1 Introduction and literature review 1.1 INTRODUCTION Animal venoms are an evolutionary adaptation to immobilise and digest prey and are used secondarily as a defence mechanism (Tu and Dekker, 1991). Intriguingly, evolutionary adaptations have produced a variety of venom proteins with specific actions and targets. A cocktail of protein and peptide toxins have varying molecular compositions, and these unique components have evolved for differing species to quickly and specifically target their prey. The compositions of venoms differ, with components varying within the toxins of spiders, stinging fish, jellyfish, octopi, cone shells, ticks, ants and snakes. Toxins have evolved for the varying mode of actions within different organisms, yet many enzymes are common to different venoms including L-amino oxidases, esterases, aminopeptidases, hyaluronidases, triphosphatases, alkaline phosphomonoesterases, 2 2 phospholipases, phosphodiesterases, serine-metalloproteases and Ca +IMg +-activated proteases. The enzymes found in venoms fall into one or more pharmacological groups including those which possess neurotoxic (causing paralysis or interfering with nervous system function), myotoxic (damaging muscle), haemotoxic (affecting the blood, -

Very Venomous, But...- Snakes of the Wet Tropics

No.80 January 2004 Notes from Very venomous but ... the Australia is home to some of the most venomous snakes in the world. Why? Editor It is possible that strong venom may little chance to fight back. There are six main snake families have evolved chiefly as a self-defence in Australia – elapids (venomous strategy. It is interesting to look at the While coastal and inland taipans eat snakes, the largest group), habits of different venomous snakes. only mammals, other venomous colubrids (‘harmless’ snakes) Some, such as the coastal taipan snakes feed largely on reptiles and pythons, blindsnakes, filesnakes (Oxyuranus scutellatus), bite their frogs. Venom acts slowly on these and seasnakes. prey quickly, delivering a large amount ‘cold-blooded’ creatures with slow of venom, and then let go. The strong metabolic rates, so perhaps it needs to Australia is the only continent venom means that the prey doesn’t be especially strong. In addition, as where venomous snakes (70 get far before succumbing so the many prey species develop a degree of percent) outnumber non- snake is able to follow at a safe immunity to snake venom, a form of venomous ones. Despite this, as distance. Taipans eat only mammals – evolutionary arms race may have been the graph on page one illustrates, which are able to bite back, viciously. taking place. very few deaths result from snake This strategy therefore allows the bites. It is estimated that between snake to avoid injury. … not necessarily deadly 50 000 and 60 000 people die of On the other hand, the most Some Australian snakes may be snake bite each year around the particularly venomous, but they are world. -

Report-Mungo National Park-Appendix A

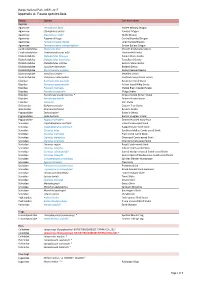

Mungo National Park, NSW, 2017 Appendix A: Fauna species lists Family Species Common name Reptiles Agamidae Ctenophorus fordi Mallee Military Dragon Agamidae Ctenophorus pictus Painted Dragon Agamidae Diporiphora nobbi Nobbi Dragon Agamidae Pogona vitticeps Central Bearded Dragon Agamidae Tympanocryptis lineata Lined Earless Dragon Agamidae Tympanocryptis tetraporophora Eyrean Earless Dragon Carphodactylidae Nephrurus levis Smooth Knob-tailed Gecko Carphodactylidae Underwoodisaurus milii Thick-tailed Gecko Diplodactylidae Diplodactylus furcosus Ranges Stone Gecko Diplodactylidae Diplodactylus tessellatus Tessellated Gecko Diplodactylidae Diplodactylus vittatus Eastern Stone Gecko Diplodactylidae Lucasium damaeum Beaded Gecko Diplodactylidae Rhynchoedura ormsbyi Eastern Beaked Gecko Diplodactylidae Strophurus elderi ~ Jewelled Gecko Diplodactylidae Strophurus intermedius Southern Spiny-tailed Gecko Elapidae Brachyurophis australis Australian Coral Snake Elapidae Demansia psammophis Yellow-faced Whip Snake Elapidae Parasuta nigriceps Mallee Black-headed Snake Elapidae Pseudechis australis Mulga Snake Elapidae Pseudonaja aspidorhyncha * Strap-snouted Brown Snake Elapidae Pseudonaja textilis Eastern Brown Snake Elapidae Suta suta Curl Snake Gekkonidae Gehyra versicolor Eastern Tree Gecko Gekkonidae Heteronotia binoei Bynoe's Gecko Pygopodidae Delma butleri Butler's Delma Pygopodidae Lialis burtonis Burton's Legless Lizard Pygopodidae Pygopus schraderi Eastern Hooded Scaly-foot Scincidae Cryptoblepharus australis Inland Snake-eyed Skink Scincidae -

Comparative Studies of the Venom of a New Taipan Species, Oxyuranus Temporalis, with Other Members of Its Genus

Toxins 2014, 6, 1979-1995; doi:10.3390/toxins6071979 OPEN ACCESS toxins ISSN 2072-6651 www.mdpi.com/journal/toxins Article Comparative Studies of the Venom of a New Taipan Species, Oxyuranus temporalis, with Other Members of Its Genus Carmel M. Barber 1, Frank Madaras 2, Richard K. Turnbull 3, Terry Morley 4, Nathan Dunstan 5, Luke Allen 5, Tim Kuchel 3, Peter Mirtschin 2 and Wayne C. Hodgson 1,* 1 Monash Venom Group, Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria 3168, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Venom Science Pty Ltd, Tanunda, South Australia 5352, Australia; E-Mails: [email protected] (F.M.); [email protected] (P.M.) 3 SA Pathology, IMVS Veterinary Services, Gilles Plains, South Australia 5086, Australia; E-Mails: [email protected] (R.K.T.); [email protected] (T.K.) 4 Adelaide Zoo, Adelaide, South Australia 5000, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected] 5 Venom Supplies, Tanunda, South Australia, South Australia 5352, Australia; E-Mails: [email protected] (N.D.); [email protected] (L.A.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-3-9905-4861; Fax: +61-3-9905-2547. Received: 5 May 2014; in revised form: 11 June 2014 / Accepted: 16 June 2014 / Published: 2 July 2014 Abstract: Taipans are highly venomous Australo-Papuan elapids. A new species of taipan, the Western Desert Taipan (Oxyuranus temporalis), has been discovered with two specimens housed in captivity at the Adelaide Zoo. This study is the first investigation of O. -

Land for Wildlife News, Alice Springs, March 2012 Jesse and Chris Recently Returned from the National Conference Down in Melbourne

LLaanndd ffoorr WWiillddlliiffee Conservation is in your hands NEWSLETTER – March 2012 Land for Wildlife News, Alice Springs, March 2012 Jesse and Chris recently returned from the national conference down in Melbourne. The Land for Wildlife program began in Victoria 30 years ago so it was only Contents fitting that the milestone be celebrated in the place of its birth. Over two days we received a comprehensive round Land for Wildlife News ........... 2 up of Land for Wildlife in all its guises around the country. Ntaria School Welcomes Land For Wildlife ................... 2 Coordinators and extension officers from every state Land for Wildlife 30 th Anniversary National Conference 2 except SA were in attendance as well as many Land for Farewell to the Albrechts – Land for Wildlife stalwarts Wildlife property owners. Also present were and Local Identities ....................................................... 2 representatives from Birdlife Australia, the Victorian Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE, and a Articles .................................... 3 variety of community conservation groups. Brown Snakes in Alice Springs ..................................... 3 Is it a stone? Is it a shoe? No... it’s a Spotted Nightjar .. 5 When a community conservation organisation can not only Pie Dish Beetle ............................................................. 7 survive but grow and thrive over three decades the news is always going to be positive. Land for Wildlife seems to be Websites Worth a Look ......... 7 going strong in all the states that it operates in, and here in Recommended Books ........... 7 The Centre, we’re doing as well or better than most of the states. Letters ..................................... 8 Central Australia is the only region where Land for Wildlife Calendar of Events ................ -

Structure±Function Properties of Venom Components from Australian Elapids

PERGAMON Toxicon 37 (1999) 11±32 Review Structure±function properties of venom components from Australian elapids Bryan Grieg Fry * Peptide Laboratory, Centre for Drug Design and Development, University of Queensland, St. Lucia, Qld, 4072, Australia Received 9 December 1997; accepted 4 March 1998 Abstract A comprehensive review of venom components isolated thus far from Australian elapids. Illustrated is that a tremendous structural homology exists among the components but this homology is not representative of the functional diversity. Further, the review illuminates the overlooked species and areas of research. # 1998 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction Australian elapids are well known to be the most toxic in the world, with all of the top ten and nineteen of the top 25 elapids with known LD50s residing exclusively on this continent (Broad et al., 1979). Thus far, three main types of venom components have been characterised from Australian elapids: prothrombin activating enzymes; lipases with a myriad of potent activities; and powerful peptidic neurotoxins. Many species have the prothrombin activating enzymes in their venoms, the vast majority contain phospholipase A2s and all Australian elapid venoms are suspected to contain peptidic neurotoxins. In addition to the profound neurological eects such as disorientation, ¯accid paralysis and respiratory failure, characteristic of bites by many species of Australian elapids is hemorrhaging and incoagulable blood. As a result, these elapids can be divided into two main classes: species with procoagulant venom (Table 1) and species with non-procoagulant venoms (Table 2) (Tan and * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed. 0041-0101/98/$ - see front matter # 1998 Elsevier Science Ltd. -

Eastern Brown Snake Fact Sheet

Eastern Brown Snake Fact Sheet Eastern Brown Snake. Image: Steve Wilson. Introduction Natural History There are nine species of brown snakes (Genus There are winners and losers in this world of rapidly Pseudonaja) in Australia. They occur over most of the changing environments. Eastern Brown Snake are certainly continent, mainly in dry areas. In a land famous for its large among the winners. The clearing of forests, creation of number of dangerous snakes, these alert, fast-moving pastures, and introduction of house mice have combined to species are among the most highly venomous. The largest, produce ideal conditions. is the Eastern Brown Snake (P. textilis) which occurs widely Eastern Brown Snakes tend to shun moist and shaded over eastern Australia. sites such as swamps and closed forests. They thrive in It may come as a surprise to learn that Eastern Brown open, sunny and lightly timbered areas such as farms, Snakes thrive on the outskirts of virtually every town and where fields and the occasional haystack are features of city between Adelaide and Cairns. They are responsible for the landscape. Sites attractive to mice, including granaries, the majority of serious snake bites in Queensland though rubbish tips, aviaries and chook sheds are particularly fortunately human fatalities are rare. Widely regarded as favoured. The mice offer a valuable food source and their highly aggressive, Eastern Brown Snakes are actually burrows are ideal shelter sites. extremely shy and spend up to 90% of their time inactive and well-hidden. If provoked, they rear their bodies and may bite savagely. However, they generally retreat swiftly at the first sign of danger, or lie unseen as people pass by.