Images and Art in Post-Revolutionary America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D4 DEACCESSION LIST 2019-2020 FINAL for HLC Merged.Xlsx

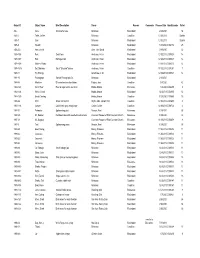

Object ID Object Name Brief Description Donor Reason Comments Process Date Box Barcode Pallet 496 Vase Ornamental vase Unknown Redundant 2/20/2020 54 1975-7 Table, Coffee Unknown Condition 12/12/2019 Stables 1976-7 Saw Unknown Redundant 12/12/2019 Stables 1976-9 Wrench Unknown Redundant 1/28/2020 C002172 25 1978-5-3 Fan, Electric Baer, John David Redundant 2/19/2020 52 1978-10-5 Fork Small form Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-7 Fork Barbeque fork Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-9 Masher, Potato Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-16 Set, Dishware Set of "Bluebird" dishes Anderson, Helen Condition 11/12/2019 C001351 7 1978-11 Pin, Rolling Grantham, C. W. Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1981-10 Phonograph Sonora Phonograph Co. Unknown Redundant 2/11/2020 1984-4-6 Medicine Dr's wooden box of antidotes Fugina, Jean Condition 2/4/2020 42 1984-12-3 Sack, Flour Flour & sugar sacks, not local Hobbs, Marian Relevance 1/2/2020 C002250 9 1984-12-8 Writer, Check Hobbs, Marian Redundant 12/3/2019 C002995 12 1984-12-9 Book, Coloring Hobbs, Marian Condition 1/23/2020 C001050 15 1985-6-2 Shirt Arrow men's shirt Wythe, Mrs. Joseph Hills Condition 12/18/2019 C003605 4 1985-11-6 Jumper Calvin Klein gray wool jumper Castro, Carrie Condition 12/18/2019 C001724 4 1987-3-2 Perimeter Opthamology tool Benson, Neal Relevance 1/29/2020 36 1987-4-5 Kit, Medical Cardboard box with assorted medical tools Covenant Women of First Covenant Church Relevance 1/29/2020 32 1987-4-8 Kit, Surgical Covenant -

Bibliography

Professor Peter Henriques, Emeritus E-Mail: [email protected] Recommended Books on George Washington 1. Paul Longmore, The Invention of GW 2. Noemie Emery, Washington: A Biography 3. James Flexner, GW: Indispensable Man 4. Richard Norton Smith, Patriarch 5. Richard Brookhiser, Founding Father 6. Marcus Cunliffe, GW: Man and Monument 7. Robert Jones, George Washington [2002 edition] 8. Don Higginbotham, GW: Uniting a Nation 9. Jack Warren, The Presidency of George Washington 10. Peter Henriques, George Washington [a brief biography for the National Park Service. $10.00 per copy including shipping.] Note: Most books can be purchased at amazon.com. A Few Important George Washington Web sites http://chnm.gmu.edu/courses/henriques/hist615/index.htm [This is my primitive website on GW and has links to most of the websites listed below plus other material on George Washington.] www.virginia.edu/gwpapers [Website for GW papers at UVA. Excellent.] http://etext.virginia.edu/washington [The Fitzpatrick edition of the GW Papers, all word searchable. A wonderful aid for getting letters on line.] http://georgewashington.si.edu [A great interactive site for students of all grades focusing on Gilbert Stuart’s Lansdowne portrait of GW.] http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/presiden/washpap.htm [The Avalon Project which contains GW’s inaugural addresses and many speeches.] http://www.mountvernon.org [The website for Mount Vernon.] Additional Books and Websites, 2004 Joe Ellis, His Excellency, October 2004 [This will be a very important book by a Pulitzer winning -

National US History Bee Round #1

National US History Bee Round 1 1. This group had a member who used the alias “Robert Rich” when writing The Brave One and who had previously written the anti-war novel Johnny Get Your Gun. This group was vindicated when member Dalton Trumbo received a credit for the movie Spartacus. Who were these screenwriters cited for contempt of Congress and blacklisted after refusing to testify before the anti-Communist HUAC? ANSWER: Hollywood Ten 052-13-92-01101 2. This man is seen pointing to a curiously bewigged child in a Grant Wood painting about his “fable.” This man invented a popular story in which a father praises the “act of heroism” of his son when the latter insists “I cannot tell a lie” after cutting down a cherry tree. Who is this man who invented numerous stories about George Washington for an 1800 biography? ANSWER: Parson Weems [or Mason Locke Weems] 052-13-92-01102 3. This building is depicted in Charles Wilson Peale’s self-portrait The Artist in His Museum. This building is where James Wilson proposed a compromise in a meeting convened after the Annapolis Convention suggested revising the Articles of Confederation. What is this Philadelphia building, the site of the Constitutional Convention? ANSWER: Independence Hall [or Old State House of Pennsylvania] 052-13-92-01103 4. This event's completion resulted in Major Ridge and Elias Boudinot's assassination by dissidents. This event was put into action after the Treaty of New Echota was signed. This event began at Red Clay, Tennessee, and many participants froze to death at places like Mantle Rock. -

The War of 1812 and American Self-Image

Educational materials developed through the Howard County History Labs Program, a partnership between the Howard County Public School System and the UMBC Center for History Education. The War of 1812 and American Self-Image Historical Thinking Skills Assessed: Sourcing, Close Reading, Corroboration Author/School/System: Emily Savopoulos, Howard County Public School System, Maryland Course: United States History Level: Middle Task Question: How did Americans' opinion of the United States change during the War of 1812? Learning Outcome: Students will be able to describe the change in opinion of Americans toward the United States during the War of 1812 based on a close reading and corroboration of two editorial cartoons. Standards Alignment: Common Core Standards for Literacy in History/Social Studies RH.6-8.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources. RH.6-8.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions. RH.6-8.7 Integrate visual information (e.g. charts, graphs, photographs, videos, or maps) with other information in print and digital texts. National History Standards Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s) Standard 3: The institutions and practices of government created during the Revolution and how they were revised between 1787 and 1815 to create the foundation of the American political system based on the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights. College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework for Social Studies Standards D2.His.2.6-8 Classify series of historical events and developments as examples of change and/or continuity. -

Rembrandt Peale, Charles Willson Peale, and the American Portrait Tradition

In the Shadow of His Father: Rembrandt Peale, Charles Willson Peale, and the American Portrait Tradition URING His LIFETIME, Rembrandt Peale lived in the shadow of his father, Charles Willson Peale (Fig. 8). In the years that Dfollowed Rembrandt's death, his career and reputation contin- ued to be eclipsed by his father's more colorful and more productive life as successful artist, museum keeper, inventor, and naturalist. Just as Rembrandt's life pales in comparison to his father's, so does his art. When we contemplate the large number and variety of works in the elder Peak's oeuvre—the heroic portraits in the grand manner, sensitive half-lengths and dignified busts, charming conversation pieces, miniatures, history paintings, still lifes, landscapes, and even genre—we are awed by the man's inventiveness, originality, energy, and daring. Rembrandt's work does not affect us in the same way. We feel great respect for his technique, pleasure in some truly beau- tiful paintings, such as Rubens Peale with a Geranium (1801: National Gallery of Art), and intellectual interest in some penetrating char- acterizations, such as his William Findley (Fig. 16). We are impressed by Rembrandt's sensitive use of color and atmosphere and by his talent for clear and direct portraiture. However, except for that brief moment following his return from Paris in 1810 when he aspired to history painting, Rembrandt's work has a limited range: simple half- length or bust-size portraits devoid, for the most part, of accessories or complicated allusions. It is the narrow and somewhat repetitive nature of his canvases in comparison with the extent and variety of his father's work that has given Rembrandt the reputation of being an uninteresting artist, whose work comes to life only in the portraits of intimate friends or members of his family. -

Defining John Bull: Political Caricature and National Identity in Late Georgian England

Published on Reviews in History (https://reviews.history.ac.uk) Defining John Bull: Political Caricature and National Identity in Late Georgian England Review Number: 360 Publish date: Saturday, 1 November, 2003 Author: Tamara Hunt ISBN: 1840142685 Date of Publication: 2003 Price: £57.50 Pages: 452pp. Publisher: Ashgate Publisher url: https://www.ashgate.com/default.aspx?page=637&calcTitle=1&title_id=1454&edition_id=1525 Place of Publication: Aldershot Reviewer: David Johnson The period between 1760 and 1820 was the golden age of British pictorial satire. But only in the last 20 years have the artists and their work attracted serious study in their own right. Rather than being seen as attractive but essentially incidental illustrations for the study of British society and politics, political and social caricatures are now analysed in depth as both a reflection of, and sometimes a formative influence upon, public opinion. Increasingly their propagandist role as tools in the hands of national government or opposition is recognised. The creators of what are often highly sophisticated and intricate images are now regarded as serious artists, and the importance of their place in the political and social world of the time recognised. The setting up of a national centre in Britain for the study of cartoons and caricature at the University of Kent at Canterbury (see http://library.kent.ac.uk/cartoons [2]) and the major James Gillray exhibition at the Tate Gallery in 2001 (see http://www.tate.org.uk/britain/exhibitions/gillray/ [3]) have set the agenda, while Diana Donald's The Age of Caricature: Satirical Prints in the Reign of George III (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1996) is currently the seminal text. -

Download Download

TEMPERANCE, ABOLITION, OH MY!: JAMES GOODWYN CLONNEY’S PROBLEMS WITH PAINTING THE FOURTH OF JULY Erika Schneider Framingham State College n 1839, James Goodwyn Clonney (1812–1867) began work on a large-scale, multi-figure composition, Militia Training (originally Ititled Fourth of July ), destined to be the most ambitious piece of his career [ Figure 1 ]. British-born and recently naturalized as an American citizen, Clonney wanted the American art world to consider him a major artist, and he chose a subject replete with American tradition and patriotism. Examining the numer- ous preparatory sketches for the painting reveals that Clonney changed key figures from Caucasian to African American—both to make the work more typically American and to exploit the popular humor of the stereotypes. However, critics found fault with the subject’s overall lack of decorum, tellingly with the drunken behavior and not with the African American stereotypes. The Fourth of July had increasingly become a problematic holi- day for many influential political forces such as temperance and abolitionist groups. Perhaps reflecting some of these pressures, when the image was engraved in 1843, the title changed to Militia Training , the title it is known by today. This essay will pennsylvania history: a journal of mid-atlantic studies, vol. 77, no. 3, 2010. Copyright © 2010 The Pennsylvania Historical Association This content downloaded from 128.118.152.206 on Thu, 21 Jan 2016 14:57:03 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions PAH77.3_02Schneider.indd 303 6/29/10 11:00:40 AM pennsylvania history demonstrate how Clonney reflected his time period, attempted to pander to the public, yet failed to achieve critical success. -

John Bull's Other Ireland

John Bull’s Other Ireland: Manchester-Irish Identities and a Generation of Performance Item Type Thesis or dissertation Authors O'Sullivan, Brendan M. Citation O'Sullivan, B. M. (2017). John Bull’s Other Ireland: Manchester- Irish identities and a generation of performance (Doctoral dissertation). University of Chester, United Kingdom. Publisher University of Chester Download date 28/09/2021 05:41:52 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/620650 John Bull’s Other Ireland Manchester-Irish Identities and a Generation of Performance Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Chester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Brendan Michael O’Sullivan May 2017 Declaration The material being presented for examination is my own work and has not been submitted for an award of this, or any other HEI except in minor particulars which are explicitly noted in the body of the thesis. Where research pertaining to the thesis has been undertaken collaboratively, the nature of my individual contribution has been made explicit. ii Table of Contents Preface .......................................................................................................... 2 Locating Theory and Method in Performance Studies and Ethnography. .. 2 Chapter 1 ..................................................................................................... 12 Forgotten but not Gone ............................................................................ 12 Chapter 2 .................................................................................................... -

Portraits in the Life of Oliver Wolcott^Jn

'Memorials of great & good men who were my friends'': Portraits in the Life of Oliver Wolcott^Jn ELLEN G. MILES LIVER woLCOTT, JR. (1760-1833), like many of his contemporaries, used portraits as familial icons, as ges- Otures in political alliances, and as public tributes and memorials. Wolcott and his father Oliver Wolcott, Sr. (i 726-97), were prominent in Connecticut politics during the last quarter of the eighteenth century and the first quarter of the nineteenth. Both men served as governors of the state. Wolcott, Jr., also served in the federal administrations of George Washington and John Adams. Withdrawing from national politics in 1800, he moved to New York City and was a successful merchant and banker until 1815. He spent the last twelve years of his public life in Con- I am grateful for a grant from the Smithsonian Institution's Research Opportunities Fund, which made it possible to consult manuscripts and see portraits in collecdüns in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, New Haven, î lartford. and Litchfield (Connecticut). Far assistance on these trips I would like to thank Robin Frank of the Yale Universit)' Art Gallery, .'\nne K. Bentley of the Massachusetts Historical Society, and Judith Ellen Johnson and Richard Malley of the Connecticut Historical Society, as well as the society's fonner curator Elizabeth Fox, and Elizabeth M. Komhauscr, chief curator at the Wadsworth Athenaeum, Hartford. David Spencer, a former Smithsonian Institution Libraries staff member, gen- erously assisted me with the VVolcott-Cibbs Family Papers in the Special Collectiims of the University of Oregon Library, Eugene; and tht staffs of the Catalog of American Portraits, National Portrait Ciallery, and the Inventory of American Painting. -

Reframing the Republic: Images and Art in Post-Revolutionary America" (2018)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University at Albany, State University of New York (SUNY): Scholars Archive University at Albany, State University of New York Scholars Archive History Honors College 5-2018 Reframing the Republic: Images and Art in Post- Revolutionary America Lauren Lyons University at Albany, State University of New York Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/ honorscollege_history Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Lyons, Lauren, "Reframing the Republic: Images and Art in Post-Revolutionary America" (2018). History. 10. https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_history/10 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at Scholars Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in History by an authorized administrator of Scholars Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reframing the Republic: Images and Art in Post-Revolutionary America An honors thesis presented to the Department of History University at Albany, State University of New York In partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with Honors in History and graduation from The Honors College. Lauren Lyons Research Mentor: Christopher Pastore, Ph.D. Second Reader: Ryan Irwin, Ph.D. May, 2018. Lyons 2 Abstract Following the American Revolution the United States had to prove they deserved to be a player on the European world stage. Images were one method the infant nation used to make this claim and gain recognition from European powers. By examining early American portraits, eighteenth and nineteenth century plays, and American and European propaganda this paper will argue that images were used to show the United States as a world power. -

Durham Research Online

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Durham Research Online Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 26 April 2019 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: O'Donoghue, Aoife (2018) '`The admixture of feminine weakness and susceptibility' : gendered personications of the state in international law.', Melbourne journal of international law., 19 (1). pp. 227-258. Further information on publisher's website: https://law.unimelb.edu.au/mjil/issues/issue-archive/191 Publisher's copyright statement: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 http://dro.dur.ac.uk ‘THE ADMIXTURE OF FEMININE WEAKNESS AND SUSCEPTIBILITY’: GENDERED PERSONIFICATIONS OF THE STATE IN INTERNATIONAL LAW Gendered Personifications of the State AOIFE O’DONOGHUE* 19th century international law textbooks were infused with the gendered personification of states. Legal academics, such as Johann Casper Bluntschli, John Westlake, Robert Phillimore and James Lorimer, relied on gendered personification to ascribe attributes to states. -

March 2015 a MESSAGE to FRIENDS Species Which Was First Found in Wales Which Remains Its Stronghold

March 2015 A MESSAGE TO FRIENDS species which was first found in Wales which remains its stronghold. A second one describes the restoration of one Shortly after the last edition went to the printers, there of the wall paintings in St Teilo’s Church which has been came the sad news of the death of Philip Lee, who re-erected in St Fagans. The article traces the significance founded this Newsletter in the 1990s and edited it for of St Roch who is the saint portrayed in the painting. some fifteen years. There is a tribute to him in this edition Finally, there is a piece by Dewi Bowen on Ivor Novello, by Judy Edwards who worked with him on editing the now primarily remembered as a song-writer but who was Newsletter from an early stage. also an actor and director. On a happier note I can report that the March 2014 edition Of course there are the regular columns: Museum News won first prize in the BafM competition for Newsletters with a pot-pourri of what is happening at the Museum’s of Groups with more than 750 members. In the BafM various sites; Friends News, which includes a piece about News section there is a piece on the award and why we the recent Friends trip to Naples and Sorrento; and From won it as well a picture of Judy Edwards, co-editor at the the Chairman in which our new Chairman introduces time, accepting the award. In addition there is news about himself. This edition also has a Book Review and a Letter the BafM AGM itself at which the award was announced.