Sheep and Goats in Developing Countries Their Present and Potential Role Public Disclosure Authorized

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustainable Goat Breeding and Goat Farming in Central and Eastern European Countries

SUSTAINABLE GOAT BREEDING AND GOAT FARMING IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES European Regional Conference on Goats 7–13 April 2014 SUSTAINABLE GOAT BREEDING AND GOAT FARMING IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES EUROPEAN EASTERN AND CENTRAL IN FARMING GOAT AND BREEDING GOAT SUSTAINABLE SUSTAINABLE GOAT BREEDING AND GOAT FARMING IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES European Regional Conference on Goats 7–13 April 2014 Edited by Sándor Kukovics, Hungarian Sheep and Goat Dairying Public Utility Association Herceghalom, Hungary FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2016 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organ- ization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not neces- sarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-109123-4 © FAO, 2016 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. -

CATAIR Appendix

CBP and Trade Automated Interface Requirements Appendix: PGA April 24, 2020 Pub # 0875-0419 Contents Table of Changes ............................................................................................................................................4 PG01 – Agency Program Codes .................................................................................................................... 18 PG01 – Government Agency Processing Codes ............................................................................................. 22 PG01 – Electronic Image Submitted Codes.................................................................................................... 26 PG01 – Globally Unique Product Identification Code Qualifiers .................................................................... 26 PG01 – Correction Indicators* ...................................................................................................................... 26 PG02 – Product Code Qualifiers.................................................................................................................... 28 PG04 – Units of Measure .............................................................................................................................. 30 PG05 – Scie nt if ic Spec ies Code .................................................................................................................... 31 PG05 – FWS Wildlife Description Codes ..................................................................................................... -

Pig Breeds and Their Characteristics - a Collection of Articles on Berkshires, the Cheshire, Jersey Reds and Many Other Varieties of Swine by Various

Pig Breeds And Their Characteristics - A Collection Of Articles On Berkshires, The Cheshire, Jersey Reds And Many Other Varieties Of Swine By Various Storey's Illustrated Breed Guide to Sheep, Goats, Cattle and Pigs: 163 Breeds from Common to Rare Sep 10, 2008. Pig Breeds and Their Characteristics The Different Breeds of Pig. American Landrace American Yorkshire Angeln Saddleback Arapawa Island. Ba Xuyen Pig Diseases; Treatment Options; Stockmanship Standards; pig characteristics are will help you to take care of these intelligent animals. Although traits may vary according to breed, several genetic characteristics We offer chicken feed with the Be sure to thoroughly research the needs of individual poultry breeds before Learnings to Help Your Birds Reach Their Full Dog Breeds and Characteristics. A brief run down on some popular breeds. These are our views on a few breeds and their traits, Hybrids in pig farming Pig breeds Pig Production Compare the different characteristics of common breeds of pigs or diseases of pigs, including their symptoms Jan 23, 2015 List of domestic pig breeds. From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Jump to: navigation, search. Deutsch: Liste der Logo Quiz Game Answers Level 8; Cheatcodes,modification & Walkthrough For Games; Logos Quiz Level 13 14 Answers (android) Bubble Games; Issue January 2012 Games Cheat pig: Yorkshire boar Larry Lefever/Grant Although originally a bacon breed, the Yorkshire rose to prominence in the characteristics: comments: Their pigs are advertised as low maintenance, durable, strong and very fertile for reproduction. What are the different breeds of pigs with their characteristics? There are 13 guinea pig breeds from which that details acceptable physical characteristics for each breed. -

Sale of Poultry, Waterfowl and Pigs Etc. Thursday 30 November 2017

Lawrie & Symington Ltd Lanark Agricultural Centre Sale of Poultry, Waterfowl and Pigs etc. Thursday 30th November 2017 Ringstock at 10.30 a.m. General Hall at 11.00 a.m Lanark Agricultural Centre Sale of Poultry and Waterfowl Special Conditions of Sale The Sale will be conducted subject to the Conditions of Sale of Lawrie and Symington Ltd as approved by the Institute of Auctioneers and Appraisers in Scotland which will be on display in the Auctioneer’s office on the day of sale. In addition the following conditions apply. 1. No animal may be sold privately prior to the sale, but must be offered for sale through the ring. 2. Animals which fail to reach the price fixed by the vendor may be sold by Private Treaty after the Auction. All such sales must be passed through the Auctioneers and will be subject to full commission. Reserve Prices should be given in writing to the auctioneer prior to the commencement of the sale. 3. All stock must be numbered and penned in accordance with the catalogued number on arrival at the market. 4. All entries offered for sale must be pre-entered in writing and paid for in full with the entries being allocated on a first come first served basis by the closing date or at 324 2x2 Cages and/or at 70 3x3 Cages, whichever is earliest. 5. No substitutes to entries will be accepted 10 days prior to the date of sale. Any substitutes brought on the sale day WILL NOT BE OFFERED FOR SALE. 6. -

First Report on the State of the World's Animal Genetic Resources"

"First Report on the State of the World’s Animal Genetic Resources" (SoWAnGR) Country Report of the United Kingdom to the FAO Prepared by the National Consultative Committee appointed by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). Contents: Executive Summary List of NCC Members 1 Assessing the state of agricultural biodiversity in the farm animal sector in the UK 1.1. Overview of UK agriculture. 1.2. Assessing the state of conservation of farm animal biological diversity. 1.3. Assessing the state of utilisation of farm animal genetic resources. 1.4. Identifying the major features and critical areas of AnGR conservation and utilisation. 1.5. Assessment of Animal Genetic Resources in the UK’s Overseas Territories 2. Analysing the changing demands on national livestock production & their implications for future national policies, strategies & programmes related to AnGR. 2.1. Reviewing past policies, strategies, programmes and management practices (as related to AnGR). 2.2. Analysing future demands and trends. 2.3. Discussion of alternative strategies in the conservation, use and development of AnGR. 2.4. Outlining future national policy, strategy and management plans for the conservation, use and development of AnGR. 3. Reviewing the state of national capacities & assessing future capacity building requirements. 3.1. Assessment of national capacities 4. Identifying national priorities for the conservation and utilisation of AnGR. 4.1. National cross-cutting priorities 4.2. National priorities among animal species, breeds, -

ELEMENTAL COMPOSITION of HUMAN and ANIMAL MILK a Review by G.V

IAEA-TECDOC-269 ELEMENTAL COMPOSITION OF HUMAN AND ANIMAL MILK A Review by G.V. IYENGAR A REPORT PREPARED UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY IN COLLABORATION WITE HTH WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION A TECHNICAL DOCUMENT ISSUED BY THE INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, VIENNA, 1982 ELEMENTAL COMPOSITION OF HUMAN AND ANIMAL MILK: A REVIEW IAEA, VIENNA, 1982 IAEA-TECDOC-269 PrinteIAEe th AustriAn y i d b a September 1982 IAEe Th A doe t maintaisno n stock f reportso thin si s series. However, microfiche copies of these reports can be obtained from INIS Clearinghouse International Atomic Energy Agency Wagramerstrasse 5 P.O. Box 100 A-1400 Vienna, Austria Orders should be accompanied by prepayment of Austrian Schillings 80.00 in the form of a cheque or in the form of IAEA microfiche service coupons orderee whicb y dhma separately fro INIe mth S Clearinghouse. PLEASE BE AWARE THAT ALL OF THE MISSING PAGES IN THIS DOCUMENT WERE ORIGINALLY BLANK FOREWORD For the past three years, the International Atomic Energy Worle Agencth dd Healtan y h Organization have been collaboratinn o g a joint research project to obtain definitive baseline data on the concentrations of twenty-four mineral and trace elements in human milk, specimens collected from nursing mothers in six Member States. Over the same period, the IAEA has also organized and provided suppor a coordinate o t d research programme, wit 3 participant1 h n i s 1 Membe1 r States n comparativo , e e studmethod th f traco yr fo se elements in human nutrition; this programme has also been concerned, inter alia, with the analysis of human milk. -

Review on Goat Milk Composition and Its Nutritive Value

Journal of Nutrition and Health Sciences Volume 3 | Issue 4 ISSN: 2393-9060 Review Article Open Access Review on Goat Milk Composition and its Nutritive Value Getaneh G*, Mebrat A, Wubie A and Kendie H University of Gondar, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Unit of Biomedical Science, Ethiopia *Corresponding author: Getaneh G, University of Gondar, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Unit of Biomedical Science, Ethiopia, E-mail: [email protected] Citation: Getaneh G, Mebrat A, Wubie A, Kendie H (2016) Review on Goat Milk Composition and Its Nutritive Value. J Nutr Health Sci 3(4): 401. doi: 10.15744/2393-9060.3.401 Received Date: August 19, 2016 Accepted Date: November 21, 2016 Published Date: November 23, 2016 Abstract Goat milk is an important nutrient for humans, especially who have problem of lactose intolerance and sensitive to other animals’ milk. Goat milk is composed of different usable nutrients which are important to their young and humans. Among those important nutrients that are found in goat milk are fat, protein, lactose, vitamins, enzymes and mineral salts. Most of the components of goat milk are greater than that of other milk producing animals. For instance, goat’s milk contains 25% more vitamin B6, 47% more vitamin A and 13% more calcium than cow’s milk. However, available information concerning goat milk is mainly limited to data on its gross composition, and information on the nutritional quality of goat milk, especially important nutritional constituents are scarce. In addition, cultural beliefs challenge the reputation of the advantage of goat milk consumption and the development of the sector, especially in developing countries. -

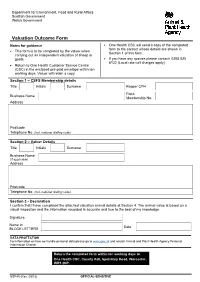

Form-Nsp45.Pdf

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Scottish Government Welsh Government Valuation Outcome Form Notes for guidance One Health CSC will send a copy of the completed form to the contact whose details are shown in This form is to be completed by the valuer when Section 1 of this form. carrying out an independent valuation of sheep or goats If you have any queries please contact: 0208 025 6122 (Local rate call charges apply). Return to One Health Customer Service Centre (CSC) in the enclosed pre-paid envelope within ten working days. Valuer will retain a copy Section 1 – CSFS Membership details Title Initials Surname Keeper CPH Flock Business Name Membership No. Address Postcode Telephone No. (incl. national dialling code) Section 2 – Valuer Details Title Initials Surname Business Name (if applicable) Address Postcode Telephone No. (incl. national dialling code) Section 3 - Declaration I confirm that I have completed the attached valuation animal details at Section 4. The animal value is based on a visual inspection and the information recorded is accurate and true to the best of my knowledge. Signature Name in Date BLOCK LETTERS DATA PROTECTION For information on how we handle personal data please go to www.gov.uk and search Animal and Plant Health Agency Personal Information Charter. Return the completed form within ten working days to: One Health CSC, County Hall, Spetchley Road, Worcester, WR5 2NP. NSP45 (Rev. 05/18) OFFICIAL-SENSITIVE Section 4 – Valuation animal details Flock Membership No. Owner name Date of valuation visit Notes for completion of table The table below must be completed by the valuer in support of the valuation pedigree certificate being available at the time of the valuation. -

Some Production Parameters of Four Breeds of Goats Reared in Trinidad and Tobago

SOME PRODUCTION PARAMETERS OF FOUR BREEDS OF GOATS REARED IN TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO H. Harricharan, F.B. Lauckner and H. Ramlal* (Cgribbean Agricultural Research & Development Institute, U.W.I. Campus, St. Augustine, Trinidad,.W.I.) SUMMARY Data on some production parameters were collected from four breeds of goats reared intensively on the Government Farm, St. Joseph, Trinidad. All animals were raised indoors. Kids were weaned from their dams within 24 hours of _birth, followed by bucket-feeding of whole goats' milk up to 12 weeks of age. In addition, the kids were fed on a commercial dairy ration and forages. The parameters determined for each breed were birth weight, weight at 12 weeks of age, average daily gain from birth to 12 weeks of age, sex ratios, prolificacy, breeding efficiency and mortality rates. The mean birth weight of Anglo Nubian, Saanen, Toggenburg, and British Alpine kids were 3.25, 2. 88,. 3.36 and 3.68 kg, respectively: Males weighed 3.37 kg and females 3.07 kg. The mean birth weight of singles, twins and triplets were 3.51, 3. 14 and 2.90 kg, respectively. The mean weight at 12 weeks of age were. 10.72, 11.47, 11.89 and 13.81 kg for Anglo Nubian, Saanen, Toggenbttrg and British Alpine, respectively. At the same age, males weighed 12.89 kg and females 10.21 kg. The 12-week weights. of singles, twins and triplets were .11.62, 11.32 and 10.90 kg, respectively. The average daily gain from birth to 12 weeks of age was 96g. -

Downloading Or Purchasing Online At

Emerging animal and plant industries Their value to Australia by Max Foster and the Agricultural Commodities Section, ABARES September 2014 RIRDC Publication No 14/069 RIRDC Project No PRJ-008496 © Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation 2013 All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-74254-685-8 ISSN 1440-6845 Emerging animal and plant industries—their value to Australia Publication No. 14/069 Project No. PRJ-008496 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the views in this publication. This publication is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. -

Pathfinder Honor Book 2014 Revision

ADRA ADRA AC&H AC&H H&S H&S HA HA NAT OI REC NAT SGO&H VOC OI REC SGO&H VOC pathfinder honor book 2014 revision general conference youth ministries department - 1 - ADRA AC&H H&S HA NAT OI REC SGO&H VOC pathfinder honor book 2014 revision general conference youth ministries department - 3 - General Conference Youth Ministries Department Director: Gilbert Cangy General Conference Associate Youth Director/Pathfinder World Director: Jonatan Tejel General Conference Honors Committee: Jonatan Tejel, Chairman Vanessa Correa, Secretary Gennady Kasap: ESD Youth Director Busi Khumalo: SID Youth Director Mark O’Ffill: NAD representative John Sommerfeld: SPD representative Paul Tompkins: TED Youth Director Jobbie Yabut: SSD Youth Director Udolcy Zukowski: SAD Pathfinder Director Copyright © 2014 by the Youth Ministries Department of the Seventh-day Adventist® Church All rights reserved. Published 2014 First edition published 1998. Second edition 2011. Third edition 2014 Rights for publishing this book outside the U.S.A. or in non-English languages are administered by the Youth Ministries Department of the Seventh-day Adventist® Church. For additional information, please visit our website, www.gcyouthministries. org, email [email protected], or write to Youth Ministries Department, General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists® Church, 12501 Old Columbia Pike, Silver Spring, MD 20904, U.S.A. Cover and inside design by Jonatan Tejel Printed in the United States of America - 4 - Table of Contents Philosophy of the Pathfinder Honors 6 Introduction -

Genetic Diversity Analyses Reveal First Insights Into Breed‐Specific

doi: 10.1111/age.12476 Genetic diversity analyses reveal first insights into breed-specific selection signatures within Swiss goat breeds † ‡ ‡ A. Burren*1, M. Neuditschko 1, H. Signer-Hasler*, M. Frischknecht*, I. Reber , F. Menzi , ‡ C. Drogem€ uller€ and C. Flury* *School of Agricultural, Forest and Food Sciences HAFL, Bern University of Applied Sciences, Langgasse€ 85, 3052 Zollikofen, Switzerland. † ‡ Swiss National Stud Farm, Agroscope Research Station, Les Longs-Pres, 1580 Avenches, Switzerland. Institute of Genetics, Vetsuisse Faculty, University of Bern, Bremgartenstrasse 109, 3001 Bern, Switzerland. Summary We used genotype data from the caprine 50k Illumina BeadChip for the assessment of genetic diversity within and between 10 local Swiss goat breeds. Three different cluster methods allowed the goat samples to be assigned to the respective breed groups, whilst the samples of Nera Verzasca and Tessin Grey goats could not be differentiated from each other. The results of the different genetic diversity measures show that Appenzell, Toggenburg, Valais and Booted goats should be prioritized in future conservation activities. Furthermore, we examined runs of homozygosity (ROH) and compared genomic inbreeding coefficients based on ROH (FROH) with pedigree-based inbreeding coefficients (FPED). The linear relationship between FROH and FPED was confirmed for goats by including samples from the three main breeds (Saanen, Chamois and Toggenburg goats). FROH appears to be a suitable measure for describing levels of inbreeding in goat breeds with missing pedigree information. Finally, we derived selection signatures between the breeds. We report a total of 384 putative selection signals. The 25 most significant windows contained genes known for traits such as: coat color variation (MITF, KIT, ASIP), growth (IGF2, IGF2R, HRAS, FGFR3) and milk composition (PITX2).