Assessment of Early Warning Efforts in Leyte for Typhoon Haiyan/Yolanda DRAFT Imprint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

EASTERN VISAYAS: SUMMARY of REHABILITATION ACTIVITIES (As of 24 Mar)

EASTERN VISAYAS: SUMMARY OF REHABILITATION ACTIVITIES (as of 24 Mar) Map_OCHA_Region VIII_01_3W_REHAB_24032014_v1 BIRI PALAPAG LAVEZARES SAN JOSE ALLEN ROSARIO BOBON MONDRAGON LAOANG VICTORIA SAN CATARMAN ROQUE MAPANAS CAPUL SAN CATUBIG ANTONIO PAMBUJAN GAMAY N O R T H E R N S A M A R LAPINIG SAN SAN ISIDRO VICENTE LOPE DE VEGA LAS NAVAS SILVINO LOBOS JIPAPAD ARTECHE SAN POLICARPIO CALBAYOG CITY MATUGUINAO MASLOG ORAS SANTA GANDARA TAGAPUL-AN MARGARITA DOLORES SAN JOSE DE BUAN SAN JORGE CAN-AVID PAGSANGHAN MOTIONG ALMAGRO TARANGNAN SANTO PARANAS NI-O (WRIGHT) TAFT CITY OF JIABONG CATBALOGAN SULAT MARIPIPI W E S T E R N S A M A R B I L I R A N SAN JULIAN KAWAYAN SAN SEBASTIAN ZUMARRAGA HINABANGAN CULABA ALMERIA CALBIGA E A S T E R N S A M A R NAVAL DARAM CITY OF BORONGAN CAIBIRAN PINABACDAO BILIRAN TALALORA VILLAREAL CALUBIAN CABUCGAYAN SANTA RITA BALANGKAYAN MAYDOLONG SAN BABATNGON ISIDRO BASEY BARUGO LLORENTE LEYTE SAN HERNANI TABANGO MIGUEL CAPOOCAN ALANGALANG MARABUT BALANGIGA TACLOBAN GENERAL TUNGA VILLABA CITY MACARTHUR CARIGARA SALCEDO SANTA LAWAAN QUINAPONDAN MATAG-OB KANANGA JARO FE PALO TANAUAN PASTRANA ORMOC CITY GIPORLOS PALOMPON MERCEDES DAGAMI TABONTABON JULITA TOLOSA GUIUAN ISABEL MERIDA BURAUEN DULAG ALBUERA LA PAZ MAYORGA L E Y T E MACARTHUR JAVIER (BUGHO) CITY OF BAYBAY ABUYOG MAHAPLAG INOPACAN SILAGO HINDANG SOGOD Legend HINUNANGAN HILONGOS BONTOC Response activities LIBAGON Administrative limits HINUNDAYAN BATO per Municipality SAINT BERNARD ANAHAWAN Province boundary MATALOM SAN JUAN TOMAS (CABALIAN) OPPUS Municipality boundary MALITBOG S O U T H E R N L E Y T E Ongoing rehabilitation Ongoing MAASIN CITY activites LILOAN MACROHON PADRE BURGOS SAN 1-30 Planned FRANCISCO SAN 30-60 RICARDO LIMASAWA PINTUYAN 60-90 Data sources:OCHA,Clusters 0 325 K650 975 1,300 1,625 90-121 Kilometers EASTERN VISAYAS:SUMMARY OF REHABILITATION ACTIVITIES AS OF 24th Mar 2014 Early Food Sec. -

Climate Disasters in the Philippines: a Case Study of the Immediate Causes and Root Drivers From

Zhzh ENVIRONMENT & NATURAL RESOURCES PROGRAM Climate Disasters in the Philippines: A Case Study of Immediate Causes and Root Drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi Benjamin Franta Hilly Ann Roa-Quiaoit Dexter Lo Gemma Narisma REPORT NOVEMBER 2016 Environment & Natural Resources Program Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org/ENRP The authors of this report invites use of this information for educational purposes, requiring only that the reproduced material clearly cite the full source: Franta, Benjamin, et al, “Climate disasters in the Philippines: A case study of immediate causes and root drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi.” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University, November 2016. Statements and views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, the Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Design & Layout by Andrew Facini Cover photo: A destroyed church in Samar, Philippines, in the months following Typhoon Yolanda/ Haiyan. (Benjamin Franta) Copyright 2016, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America ENVIRONMENT & NATURAL RESOURCES PROGRAM Climate Disasters in the Philippines: A Case Study of Immediate Causes and Root Drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi Benjamin Franta Hilly Ann Roa-Quiaoit Dexter Lo Gemma Narisma REPORT NOVEMBER 2016 The Environment and Natural Resources Program (ENRP) The Environment and Natural Resources Program at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs is at the center of the Harvard Kennedy School’s research and outreach on public policy that affects global environment quality and natural resource management. -

NPH, ERC Case No. 2016-162 RC

" r_\)l.ATOR'r-C'~~ '(,.u ., c;\~ v1.~i"-~ 'l Aooroved for % ; Li..J I 1. :z: J Posting Republic of the Philippines ,\ www.erc.gov.ph ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION- W 12r",) 1,'1 San Miguel Avenue, Pasig City ~ IN THE MATTER OF THE APPLICATION FOR THE APPROVAL OF EMERGENCY CAPITAL EXPENDITURE PROJECTS 2015-2016 OF LEYTE V ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE, INC. (LEYECO V) WITH AUTHORITY TO SECURE LOAN AND MOTION FOR THE ISSUANCE OF PROVISIONAL 'AUTHORITY, ERC CASE NO. 2016 -162 RC LEYTE V ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE, INC. (LEYECOV), Applicant. )(-------------------------------------)( NOTICE OF PUBLIC HEARING TO ALL INTERESTED PARTIES: Notice is hereby given that on 18 August 2016, Leyte V Electric Cooperative, Inc. (LEYECO V) filed an Application (With Motion for the Issuance of Provisional Authority) seeking the Commission's approval of its Emergency Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) Projects for 2015-2016, with authority to secure loan. LEYECO V alleged the following in its Application: I. THE APPLICANT 1. The applicant, LEYECO V is a non-stock, non-profit Electric Cooperative duly organized and existing under and by virtue of the Presidential Decree 269, as amended, with capacity to sue and be sued, with principal office address at San Pablo, Ormoc City, Leyte where it may be served with summons and ERC CASE NO. 2016-162 RC ORDER/ 8 DECEMBER 2016 PAGE20F13 NO.125 series of 2015 dated November 30, 2015, copy of which is hereto attached as "Annex A". 2. Herein applicant is the exclusive franchise holder issued by the National Electrification Administration (NEA) to operate an electric light and power services in the City of Ormoc and 11 municipalities in the 3rd & 4th Congressional Districts of Leyte Province. -

The Impact of Tropical Cyclone Hayan in the Philippines: Contribution of Spatial Planning to Enhance Adaptation in the City of Tacloban

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS Faculdade de Ciências Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas Faculdade de Letras Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia Instituto de Ciências Sociais Instituto Superior de Agronomia Instituto Superior Técnico The impact of tropical cyclone Hayan in the Philippines: Contribution of spatial planning to enhance adaptation in the city of Tacloban Doutoramento em Alterações Climáticas e Políticas de Desenvolvimento Sustentável Especialidade em Ciências do Ambiente Carlos Tito Santos Tese orientada por: Professor Doutor Filipe Duarte Santos Professor Doutor João Ferrão Documento especialmente elaborado para a obtenção do grau de Doutor 2018 UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS Faculdade de Ciências Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas Faculdade de Letras Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia Instituto de Ciências Sociais Instituto Superior de Agronomia Instituto Superior Técnico The impact of tropical cyclone Haiyan in the Philippines: Contribution of spatial planning to enhance adaptation in the city of Tacloban Doutoramento em Alterações Climáticas e Políticas de Desenvolvimento Sustentável Especialidade em Ciências do Ambiente Carlos Tito Santos Júri: Presidente: Doutor Rui Manuel dos Santos Malhó; Professor Catedrático Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa Vogais: Doutor Carlos Daniel Borges Coelho; Professor Auxiliar Departamento de Engenharia Civil da Universidade de Aveiro Doutor Vítor Manuel Marques Campos; Investigador Auxiliar Laboratório Nacional de Engenharia Civil(LNEC) -

Typhoon Haiyan Action Plan November 2013

Philippines: Typhoon Haiyan Action Plan November 2013 Prepared by the Humanitarian Country Team 100% 92 million total population of the Philippines (as of 2010) 54% 50 million total population of the nine regions hit by Typhoon Haiyan 13% 11.3 million people affected in these nine regions OVERVIEW (as of 12 November) (12 November 2013 OCHA) SITUATION On the morning of 8 November, category 5 Typhoon Haiyan (locally known as Yolanda ) made a direct hit on the Philippines, a densely populated country of 92 million people, devastating areas in 36 provinces. Haiyan is possibly the most powerful storm ever recorded . The typhoon first ma de landfall at 673,000 Guiuan, Eastern Samar province, with wind speeds of 235 km/h and gusts of 275 km/h. Rain fell at rates of up to 30 mm per hour and massive storm displaced people surges up to six metres high hit Leyte and Samar islands. Many cities and (as of 12 November) towns experienced widespread destruction , with as much as 90 per cent of housing destroyed in some areas . Roads are blocked, and airports and seaports impaired; heavy ships have been thrown inland. Water supply and power are cut; much of the food stocks and other goods are d estroyed; many health facilities not functioning and medical supplies quickly being exhausted. Affected area: Regions VIII (Eastern Visayas), VI (Western Visayas) and Total funding requirements VII (Central Visayas) are hardest hit, according to current information. Regions IV-A (CALABARZON), IV-B ( MIMAROPA ), V (Bicol), X $301 million (Northern Mindanao), XI (Davao) and XIII (Caraga) were also affected. -

WMO Statement on the Status of the Global Climate in 2011

WMO statement on the status of the global climate in 2011 WMO-No. 1085 WMO-No. 1085 © World Meteorological Organization, 2012 The right of publication in print, electronic and any other form and in any language is reserved by WMO. Short extracts from WMO publications may be reproduced without authorization, provided that the complete source is clearly indicated. Editorial correspondence and requests to publish, reproduce or translate this publication in part or in whole should be addressed to: Chair, Publications Board World Meteorological Organization (WMO) 7 bis, avenue de la Paix Tel.: +41 (0) 22 730 84 03 P.O. Box 2300 Fax: +41 (0) 22 730 80 40 CH-1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978-92-63-11085-5 WMO in collaboration with Members issues since 1993 annual statements on the status of the global climate. This publication was issued in collaboration with the Hadley Centre of the UK Meteorological Office, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland; the Climatic Research Unit (CRU), University of East Anglia, United Kingdom; the Climate Prediction Center (CPC), the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC), the National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service (NESDIS), the National Hurricane Center (NHC) and the National Weather Service (NWS) of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States of America; the Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) operated by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), United States; the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), United States; the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), United Kingdom; the Global Precipitation Climatology Centre (GPCC), Germany; and the Dartmouth Flood Observatory, United States. -

March 2020 PSA Leytest Newsbits 2

The Official Quarterly Newsletter of PSA Leyte PSA Leyte celebrates 30th Civil Registration Month Couples during the mass wedding in Ormoc City on Februry 13, 2020 Grade 10 students of Ormoc City during the Civil Registratiojn Quiz Anchored on the theme “Shaping Civil Registration and Vital Statistics (CRVS) by embracing new trends in the 4th Industrial Revolution (4IR),” the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA)- Leyte Provincial Statistical Office conducted activities targeted at framing a strong and qualitative civil registration system in the province, in collaboration with Local Civil Registry Offices. This is in connection with the annual observance of Civil Registration Month every February wherein civil registration activities are in its full blast. For this year, the month-long celebration was started by its Launching and Caravan on January 31 to February 1, 2020, hosted by the Local Government Unit (LGU) of Matalom, Leyte. One hundred seventy- three (173) City/Municipal Civil Registrars (C/MCRs) and their staff graced said event. to page 2 Leyte LGUs support 2020 CPH In preparation for the conduct of the 2020 Census of Population and Housing (CPH), PSA-Leyte conducted convening and information dissemination activities in the cities/municipalities of the province. Above activities were conducted as early as November 2019. Members of City/Municipal Census CSS Jamisola discusses 2020 CPH to MCCB Chair and members of Coordinating Boards (C/MCCB) Palo, Leyte of LGUs in Leyte were convened by PSA in order to discuss about their roles in the upcoming 2020 CPH operation. These were done together with the presentation of the highlights of the to page 2 January-March 2020 PSA LEYTEst Newsbits 2 Mr. -

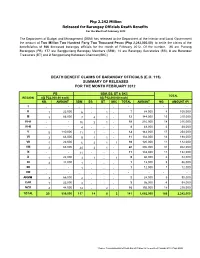

SUMMARY of RELEASES Php 2.242 Million Released for Barangay

Php 2.242 Million Released for Barangay Officials Death Benefits For the Month of February 2012 The Department of Budget and Management (DBM) has released to the Department of the Interior and Local Government the amount of Two Million Two Hundred Forty Two Thousand Pesos (Php 2,242,000.00) to settle the claims of the beneficiaries of 166 deceased barangay officials for the month of February 2012. Of the number, 25 are Punong Barangays (PB), 177 are Sangguniang Barangay Members (SBM), 14 are Barangay Secretaries (BS), 8 are Barangay Treasurers (BT) and 2 Sangguniang Kabataan Chairmen(SKC). DEATH BENEFIT CLAIMS OF BARANGAY OFFICIALS (E.O. 115) SUMMARY OF RELEASES FOR THE MONTH FEBRUARY 2012 PB SBM, BS, BT & SKC TOTAL REGION (@ P22,000.00 each) (@ P12,000.00 each) NO. AMOUNT SBM BS BT SKC TOTAL AMOUNT NO. AMOUNT (P) I - - - - - - - - - - II 1 22,000 6 - 1 - 7 84,000 8 106,000 III 3 66,000 7 4 1 - 12 144,000 15 210,000 IV-A - - 15 2 1 - 18 216,000 18 216,000 IV-B - - 4 - - - 4 48,000 4 48,000 V 5 110,000 11 1 - - 12 144,000 17 254,000 VI 3 66,000 9 1 1 - 11 132,000 14 198,000 VII 1 22,000 6 2 1 1 10 120,000 11 142,000 VIII 3 66,000 24 3 1 - 28 336,000 31 402,000 IX - - 11 - - - 11 132,000 11 132,000 X 1 22,000 3 1 - 1 5 60,000 6 82,000 XI 2 44,000 1 - - - 1 12,000 3 56,000 XII - - 1 - - - 1 12,000 1 12,000 XIII - - - - - - - - - - ARMM 3 66,000 2 - - - 2 24,000 5 90,000 CAR 1 22,000 3 - - - 3 36,000 4 58,000 NCR 2 44,000 14 - 2 - 16 192,000 18 236,000 TOTAL 25 550,000 117 14 8 2 141 1,692,000 166 2,242,000 *Source: Consolidated List of Death Benefit Claims for the month of February 2012 Php2.242M DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT (DILG) NATIONAL BARANGAY OPERATIONS OFFICE (NBOO) Consolidated List of Death Benefit Claims and Amount to be Paid to Barangay Oficials FEBRUARY 2012 NO. -

Trials and Tribulations in Locating Tree Farmers and Sites for Research and Extension Activities

15. TRIALS AND TRIBULATIONS IN LOCATING TREE FARMERS AND SITES FOR RESEARCH AND EXTENSION ACTIVITIES Edwin Cedamon, Samuel Bernaldez and Jack Baynes The major aim of ACIAR project ASEM 2003/052 is to improve financial returns to existing smallholder tree farms in Leyte through a number of extension activities. In order to identify sites suitable for extension activities, visits were made to some tree farms (either registered or not registered with DENR) in Leyte. For this purpose, the initial aim was to identify at least 30 tree farms representing a range of age classes, species, soil types, elevation and climate. In addition, tree farms should have an area of at least 0.25 ha. Various difficulties were encountered in fieldwork designed to locate these tree farms. The main reason was associated with inconsistencies in the database of registered tree farms compiled by Community Environment and Natural Resources Offices (CENROs) which included information concerning tree farm location, owner, species and plantation area. Specific difficulties encountered in finding sites included nonexistence of some registered tree farms, inability to interview some farm owners because they do not reside near their tree farm, some tree farms have a low stocking against what was listed with the CENRO. Despite these difficulties, 76 tree farms were found during October to December 2004. Seventy one tree farms were GPS referenced and 37 tree farm owners were interviewed. INTRODUCTION ACIAR Project ASEM 2003/052 – titled ‘Improving financial returns to smallholder tree farmers in the Philippines’ involves cooperative research between staff of the College of Forestry at Leyte State University, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) and Australian researchers. -

Chec List Amphibians and Reptiles, Romblon Island

Check List 8(3): 443-462, 2012 © 2012 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (available at www.checklist.org.br) Journal of species lists and distribution Amphibians and Reptiles, Romblon Island Group, central PECIES Philippines: Comprehensive herpetofaunal inventory S OF Cameron D. Siler 1*, John C. Swab 1, Carl H. Oliveros 1, Arvin C. Diesmos 2, Leonardo Averia 3, Angel C. ISTS L Alcala 3 and Rafe M. Brown 1 1 University of Kansas, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Biodiversity Institute, Lawrence, KS 66045-7561, USA. 2 Philippine National Museum, Zoology Division, Herpetology Section. Rizal Park, Burgos St., Manila, Philippines. 3 Silliman University Angelo King Center for Research and Environmental Management, Dumaguete City, Negros Oriental, Philippines. * Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: We present results from several recent herpetological surveys in the Romblon Island Group (RIG), Romblon Province, central Philippines. Together with a summary of historical museum records, our data document the occurrence of 55 species of amphibians and reptiles in this small island group. Until the present effort, and despite past studies, observations of evolutionarily distinct amphibian species, including conspicuous, previously known, endemics like the forestherpetological frogs Platymantis diversity lawtoni of the RIGand P.and levigatus their biogeographical and two additional affinities suspected has undescribedremained poorly species understood. of Platymantis We . reportModerate on levels of reptile endemism prevail on these islands, including taxa like the karst forest gecko species Gekko romblon and the newly discovered species G. coi. Although relatively small and less diverse than the surrounding landmasses, the islands of Romblon Province contain remarkable levels of endemism when considered as percentage of the total fauna or per unit landmass area. -

2018 Operation Timbang Plus Report Municipal Ranking Weight for Age: Underweight+Severely Underweight

2018 OPERATION TIMBANG PLUS REPORT MUNICIPAL RANKING WEIGHT FOR AGE: UNDERWEIGHT+SEVERELY UNDERWEIGHT Rank Province Municipality Magnitude Prevalence 1 Northern Samar SILVINO LOBOS 224 23.4% 2 Western Samar SAN JOSE DE BUAN 178 22.4% 3 Western Samar TAGAPUL-AN 165 21.7% 4 Northern Samar MAPANAS 231 19.6% 5 Western Samar ALMAGRO 94 19.6% 6 Western Samar PINABACDAO 296 18.6% 7 Northern Samar SAN ROQUE 483 18.3% 8 Eastern Samar JIPAPAD 125 18.0% 9 Western Samar SAN SEBASTIAN 100 17.4% 10 Western Samar STO. NIǸO 171 17.2% 11 Western Samar MATUGINAO 144 17.1% 12 Western Samar GANDARA 396 17.0% 13 Western Samar MOTIONG 201 16.8% 14 Western Samar SAN JORGE 195 16.8% 15 Eastern Samar SAN JULIAN 192 16.4% 16 Northern Samar SAN VICENTE 82 16.3% 17 Western Samar VILLAREAL 403 16.3% 18 Leyte KANANGA 792 16.1% 19 Western Samar PAGSANGHAN 112 16.0% 20 Leyte LA PAZ 215 15.5% 21 Northern Samar MONDRAGON 553 15.3% 22 Northern Samar ROSARIO 171 15.2% 23 Leyte MATAG-OB 234 14.9% 24 Northern Samar LAVEZARES 407 14.7% 25 Western Samar CALBIGA 253 14.5% 26 Northern Samar LOPE DE VEGA 222 14.5% 27 Western Samar DARAM 614 14.3% 28 Western Samar BASEY 534 13.7% 29 Eastern Samar BALANGIGA 190 13.7% 30 Biliran BILIRAN 220 13.6% 31 Western Samar ZUMARRAGA 179 13.5% 32 Northern Samar BIRI 122 13.4% 33 Northern Samar PAMBUJAN 448 13.4% 34 Leyte BATO 457 13.4% 35 Leyte PALO 884 13.3% 36 Eastern Samar ORAS 387 13.1% 37 Northern Samar LAOANG 686 12.9% 38 Western Samar STA.