Philosophy of Magic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Theme Park As "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," the Gatherer and Teller of Stories

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories Carissa Baker University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Rhetoric Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Baker, Carissa, "Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5795. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5795 EXPLORING A THREE-DIMENSIONAL NARRATIVE MEDIUM: THE THEME PARK AS “DE SPROOKJESSPROKKELAAR,” THE GATHERER AND TELLER OF STORIES by CARISSA ANN BAKER B.A. Chapman University, 2006 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2018 Major Professor: Rudy McDaniel © 2018 Carissa Ann Baker ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the pervasiveness of storytelling in theme parks and establishes the theme park as a distinct narrative medium. It traces the characteristics of theme park storytelling, how it has changed over time, and what makes the medium unique. -

Coffeeville Edits

Christopher Welsh 1005 Inland Lane McKinney, TX 75070 (approximately 14,700 words) 407-574-3423 [email protected] Coffeyville By C.E.L. Welsh Harry slowed his breathing. Across from him, no more than twenty 20 paces away, a man aimed a gun at his heart and meant to fire. Harry wanted to keep his eyes on the gun barrel, that dot of empty blackness that would spit out a metal slug with his name on it, but he knew he should be watching the man's shoulders, his chest, his stomach; —all key areas where a man might tense, moments before he pulled the trigger. He should, but he couldn't. Harry watched none of these areas. Instead, he fixed on the gunman's eyes. Each of his His eyes where washeterochromatic; each a different color. That alone wouldn't be enough to draw in Harry, to cause him to risk making a mistake at this very crucial moment; it was the quality—the nature—of the heterochromatic eyes that drew him in. The right eye was a pale blue that reflected and amplified the stage lights surrounding them, seeming to shine under it's its own power. The left eye was a dull, steely gray that pulled light in, muting it, and causing the right eye to practically glow in the contrast. In addition, the man's eyes radiated something akin to hate...was it bitterness? Disgust? Whatever it was, the crowd surrounding the men seemed sure that the man with the gun had every intention of firing when the moment was right. -

Pressive Cast of Thinkers and Performers

Table of Contents Long Synopsis Short Synopsis Michael Caplan Biography Key Production Personnel Filmography Credit List Magicians & Scholars Cover design by Lara Marsh, Illustration by Michael Pajon A Magical Vision /Long Synopsis ______________________________________________________ A Magical Vision spotlights Eugene Burger, a far-sighted philosopher and magician who is considered one of the great teachers of the magical arts. Eugene has spent twenty-five years speaking to magicians, academics, and the general public about the experience of magic. Advocating a return to magic’s shamanistic, healing traditions, Eugene’s “magic tricks” seek to evoke feelings of awe and transcendence, and surpass the Las Vegas-style entertainment so many of us visualize when we think of magicians. Mentors and colleagues have emerged throughout Eugene’s globe-trotting career. Among them is Jeff McBride, a recognized innovator of contemporary magic, and Max Maven, a one-man-show who performs a unique brand of “mind magic” to audiences worldwide. Lawrence Hass created the world’s first magic program in a liberal arts setting, where his seminar has attracted an impressive cast of thinkers and performers. The film, however, is Eugene’s journey. It began in 1940s Chicago, a city already renowned as the center of classic magic performance. Yale Divinity School followed, leading Eugene to the world of Asian mysticism. From there came the creation of Hauntings, a tribute to the sprit theatre of the 19th century, and the gore of the Bizarre Magick movement. Today Eugene’s performances and lectures draw inspiration from the mythology of India to the Buddhism of magical theory. On this stage, the magicians and thinkers open doors to an astounding world, a world that we rarely take time to see. -

March 6 Special Interest Groups DVR ALERT from DAVE

The SPIRIT | Official Newsletter of I.B.M. Ring 1 Meeting Update: March 6th M Arch 2 01 3 Special Interest Groups Volume 13, Issue 3 Inside this issue: The March 6 meeting program will feature “Special Interest Groups.” Three instructors will each simultaneously present 45 minute “hands on” teach-ins. Each instructor will only present 2 programs. You may select Meeting Update 1 any two of the three programs and when you have participated in your first program, you will then move on to your second program choice. DVR ALERT 1 Choices: Magic Past 2 Randy Kalin will present effective but simple card tricks with most being Ring Report 3-4 based on mathematical principles without difficult sleights. Schedule of Events 3 Mike Hindrichs, our close-up contest winner, will present his rope magic including routines and individual moves. Dues Info 4 Harry Monti will present the “Linking Rings.” He will demonstrate a Lecture Info 5 routine and then break it down and show the various elements. JDRF Info 6 These are “hands on” programs to be sure so bring your own cards, JDRF Photos 7 ropes and rings. Contest Winners 7 Harry Monti This Just In 8 NEW MEETING AGENDA 6:30 Magic 101 Quiet Please if you are not involved with Magic 101. 7:00 Refreshments/ Socialize and Jamming sessions 7:30 Special Interest Groups QUOTE: Following the meeting- Workshop and Fellowship till 10PM “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” DVR ALERT FROM DAVE Arthur C. Clarke, Profiles of the Future: An Inquiry into the Limits of the David Copperfield posted this on Facebook- Possible “Breaking news! Excited to announce that I will be hosting magic on the Today Show EVERY Monday in March! It starts this Monday on NBC.” 2 From The Magic Past \ By Don Rataj Here is an update that I have listed in Magicpedia, however I am missing several years. -

ICLA 2016 – Abstracts Group Session Panels Content Computational Comparative Literature

ICLA 2016 – Abstracts Group Session Panels, July 17th, 2016 ICLA 2016 – Abstracts Group Session Panels Content Computational Comparative Literature. Corpus-based Methodologies ................................................. 5 16082 - Assia Djebar et la transgression des limites linguistiques, littéraires et culturelles .................. 7 16284 - Pictures for Everybody! Postcards and Literature/ Bilder für alle! Postkarten und Literatur . 11 16309 - Talking About Literature, Scientifically..................................................................................... 14 16377 - Sprache & Rache ...................................................................................................................... 16 16416 - Translational Literature - Theory, History, Perspectives .......................................................... 18 16445 - Langage scientifique, langage littéraire : quelles médiations ? ............................................... 24 16447 - PANEL Digital Humanities in Comparative Literature, World Literature(s), and Comparative Cultural Studies ..................................................................................................................................... 26 16460 - Kolonialismus, Globalisierung(en) und (Neue) Weltliteratur ................................................... 31 16499 - Science et littérature : une question de langage? ................................................................... 40 16603 - Rhizomorphe Identität? Motivgeschichte und kulturelles Gedächtnis im -

Biblioteca Digital De Cartomagia, Ilusionismo Y Prestidigitación

Biblioteca-Videoteca digital, cartomagia, ilusionismo, prestidigitación, juego de azar, Antonio Valero Perea. BIBLIOTECA / VIDEOTECA INDICE DE OBRAS POR TEMAS Adivinanzas-puzzles -- Magia anatómica Arte referido a los naipes -- Magia callejera -- Música -- Magia científica -- Pintura -- Matemagia Biografías de magos, tahúres y jugadores -- Magia cómica Cartomagia -- Magia con animales -- Barajas ordenadas -- Magia de lo extraño -- Cartomagia clásica -- Magia general -- Cartomagia matemática -- Magia infantil -- Cartomagia moderna -- Magia con papel -- Efectos -- Magia de escenario -- Mezclas -- Magia con fuego -- Principios matemáticos de cartomagia -- Magia levitación -- Taller cartomagia -- Magia negra -- Varios cartomagia -- Magia en idioma ruso Casino -- Magia restaurante -- Mezclas casino -- Revistas de magia -- Revistas casinos -- Técnicas escénicas Cerillas -- Teoría mágica Charla y dibujo Malabarismo Criptografía Mentalismo Globoflexia -- Cold reading Juego de azar en general -- Hipnosis -- Catálogos juego de azar -- Mind reading -- Economía del juego de azar -- Pseudohipnosis -- Historia del juego y de los naipes Origami -- Legislación sobre juego de azar Patentes relativas al juego y a la magia -- Legislación Casinos Programación -- Leyes del estado sobre juego Prestidigitación -- Informes sobre juego CNJ -- Anillas -- Informes sobre juego de azar -- Billetes -- Policial -- Bolas -- Ludopatía -- Botellas -- Sistemas de juego -- Cigarrillos -- Sociología del juego de azar -- Cubiletes -- Teoria de juegos -- Cuerdas -- Probabilidad -

Attention and Awareness in Stage Magic: Turning Tricks Into Research

PERSPECTIVES involve higher-level cognitive functions, SCIENCE AND SOCIETY such as attention and causal inference (most coin and card tricks used by magicians fall Attention and awareness in stage into this category). The application of all these devices by magic: turning tricks into research the expert magician gives the impression of a ‘magical’ event that is impossible in the physical realm (see TABLE 1 for a classifica- Stephen L. Macknik, Mac King, James Randi, Apollo Robbins, Teller, tion of the main types of magic effects and John Thompson and Susana Martinez-Conde their underlying methods). This Perspective addresses how cognitive and visual illusions Abstract | Just as vision scientists study visual art and illusions to elucidate the are applied in magic, and their underlying workings of the visual system, so too can cognitive scientists study cognitive neural mechanisms. We also discuss some of illusions to elucidate the underpinnings of cognition. Magic shows are a the principles that have been developed by manifestation of accomplished magic performers’ deep intuition for and magicians and pickpockets throughout the understanding of human attention and awareness. By studying magicians and their centuries to manipulate awareness and atten- tion, as well as their potential applications techniques, neuroscientists can learn powerful methods to manipulate attention to research, especially in the study of the and awareness in the laboratory. Such methods could be exploited to directly study brain mechanisms that underlie attention the behavioural and neural basis of consciousness itself, for instance through the and awareness. This Perspective therefore use of brain imaging and other neural recording techniques. seeks to inform the cognitive neuroscientist that the techniques used by magicians can be powerful and robust tools to take to the Magic is one of the oldest and most wide- powers. -

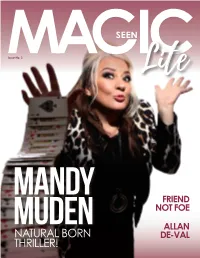

Counter Intelligence Is the Latest of a 36 Page Printed Booklet Which Do and It Is Completely Baffling, Release from the Brilliant Mind of Is Clear and Concise

Issue No. 3 Lite MANDY FRIEND MUDEN NOT FOE ALLAN NATURAL BORN DE-VAL THRILLER! THE OPENER A WORD FROM THE EDITOR ow, we are into in Comedy Clubs after giving helps to fill us in on everything our third edition up her attempts to become an that is happening in this niche of Magicseen Lite actress, and although her rise entertainment world. already, yet it only has been steady rather than seems minutes meteoric, her good showing on What else have we extracted from sensible buying decisions. ago that we Britain’s Got Talent has helped the full September Magicseen If you enjoy this free taster edition Wdecided to go ahead with the to firmly established her act. We to include here? Well, there’s of Magicseen, maybe we can project at all! It’s great to see are delighted to provide further Friend Not Foe, which is an article tempt you to sign up for the that lots of readers are taking background on her for you to exploring how we can harness whole thing! We have 1 or 2 year advantage of these special enjoy in this issue. the ‘comedian’ in the audience printed copy or download subs taster issues and we hope to enhance our act rather than available, and subscribers not that you will enjoy this latest Escapology is an allied art to destroy it, we offer a Masterclass only get the full versions of every one too. magic that we rarely get to routine from David Regal’s brand issue 6 times a year, they also feature in Magicseen, so we are new book Interpreting Magic, we get other benefits too. -

The Salt City Magic Club August 2017

The Salt City Magic Club August 2017 This ’n’ That By B ruce Purdy What have you been up on it. working on this Summer? Whatever you’ve got, bring it Along with Bob Holland’s along to share with the group. “Close-Up” mini-lecture, we will have plenty of time to Are you having prob- “Session” together. Show us lems with a move, are develop- your latest projects. ing ideas for a new routine or Harris Solomon forgot how that old gizmo works Have you bought some or what it does? looking for A monthly newsletter of the new Magic? Been practicing a feedback on a routine? We stand Harris A. Solomon Ring #74 new card trick or sponge ball ready to help. International Brotherhood of Magicians routine? Maybe you pulled (the Salt City Magic Club) something out of your drawer I look forward to seeing President: Theresa Barniak that you haven’t used in a long you at the August meeting on Vice President: David Jackman time and have been brushing the 17th! Secretary: Ken Frehm Treasurer: Bruce Purdy Sgt. At Arms: David Hanselman Oops!! plied to my Facebook post that IBM Ring #74 meets at 7:30pm I realised - There NO meeting the Third Thursday of every month I showed up early for scheduled, as the 4th of July At Timber Tavern (See page 7 ) the meeting on 20th July. I picnic served as our “July meet- couldn’t understand why no one Please submit material for publication in the Wandogram to: ing”! else showed up until 7:30 when [email protected] the meeting was supposed to or by Snail Mail: D’oh! start. -

Rare Posters

Public Auction #009 Rare Posters Conjuring, Circus, and Allied Arts For sale at public auction March 26 2011 at 11:00 am Exhibition March 22 - 25 Potter & Potter Auctions, Inc. 3729 N. Ravenswood Ave. -Suite 116- Chicago, IL 60613 Thank you for downloading the digital edition of this catalog. Hard copies can be purhased at our website, www.potterauctions.com. To view detailed, color images of each lot and to place bids online for items in this catalog, please visit our partner website, www.liveauctioneers.com. Introduction Magic is the oldest of the theatrical arts. Its earliest origins was frequently shown with diminutive red devils or imps were in Shamanism and the priesthood. By the time of ancient perched on his shoulder or whispering (presumably arcane Egypt, clever conjurors were using many of the same tricks secrets) in his ear. Some of these portraits include a background performed by magicians today to convince the masses of their which suggests that the person pictured is a magician or the supernatural power. In the thousands of years since its earliest portrait itself is stylized in such a manner as to suggest that recorded beginnings, magic moved from the temples of ancient the person is a mystery worker or, at the very least, an exotic times to the street corners and fairs of the Middle Ages, then personality. Notable in this regard are the portrait lithographs into taverns and drawing rooms and, finally, onto the stage and of Chung Ling Soo, Alexander, and Cater. Also in this category television. are some posters which only vaguely suggest an illusion being When the art of conjuring split from its religious and performed, such as the poster for The Great Rameses. -

The Underground Sessions Page 36

MAY 2013 TONY CHANG DAN WHITE DAN HAUSS ERIC JONES BEN TRAIN THE UNDERGROUND SESSIONS PAGE 36 CHRIS MAYHEW MAY 2013 - M-U-M Magazine 3 MAGIC - UNITY - MIGHT Editor Michael Close Editor Emeritus David Goodsell Associate Editor W.S. Duncan Proofreader & Copy Editor Lindsay Smith Art Director Lisa Close Publisher Society of American Magicians, 6838 N. Alpine Dr. Parker, CO 80134 Copyright © 2012 Subscription is through membership in the Society and annual dues of $65, of which $40 is for 12 issues of M-U-M. All inquiries concerning membership, change of address, and missing or replacement issues should be addressed to: Manon Rodriguez, National Administrator P.O. Box 505, Parker, CO 80134 [email protected] Skype: manonadmin Phone: 303-362-0575 Fax: 303-362-0424 Send assembly reports to: [email protected] For advertising information, reservations, and placement contact: Mona S. Morrison, M-U-M Advertising Manager 645 Darien Court, Hoffman Estates, IL 60169 Email: [email protected] Telephone/fax: (847) 519-9201 Editorial contributions and correspondence concerning all content and advertising should be addressed to the editor: Michael Close - Email: [email protected] Phone: 317-456-7234 Submissions for the magazine will only be accepted by email or fax. VISIT THE S.A.M. WEB SITE www.magicsam.com To access “Members Only” pages: Enter your Name and Membership number exactly as it appears on your membership card. 4 M-U-M Magazine - MAY 2013 M-U-M MAY 2013 MAGAZINE Volume 102 • Number 12 26 28 36 PAGE STORY 27 COVER S.A.M. NEWS 6 From -

[email protected]

[email protected] Sherman, Texas ‐ Lawrence Hass is professor of humanities at Austin College. He also has an international reputation as a sleight of hand magician and holds the position of associate dean of Jeff McBride’s Magic & Mystery School in Las Vegas. Dr. Hass came to Austin College in July of 2009 when his wife Dr. Marjorie Hass became the College’s 15th president. Prior to this, he was professor of philosophy and theatre arts at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pennsylvania, where he was an award‐winning teacher of philosophy and theatre, specializing in phenomenology, aesthetics, magic performance, and the history and philosophy of magic. During his 18‐year tenure at Muhlenberg College, Dr. Hass founded and directed the “Theory and Art of Magic” program—a college‐level co‐curricular program that was dedicated to the study and appreciation of the magical arts. From 1999 to 2009, the “Theory and Art of Magic” program featured performances, talks, and lectures by such world‐leading stars of magic as David Blaine, Eugene Burger, Roberto Giobbi, Max Howard, René Lavand, Max Maven, Jeff McBride, Robert E. Neale, Jim Steinmeyer, Juan Tamariz, and Teller (among many others). By the end of its 11‐year run, the “Theory and Art of Magic” program was drawing attendees—magicians, students, and scholars of magic—from all over the country and internationally. As an outgrowth of the program, Dr. Hass founded Theory and Art of Magic Press in 2007 to publish books, DVDs, and other materials that would connect with people wanting to perform and think about magic in a deeper way.