Origins of Reclamation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thesis-1972D-C289o.Pdf (5.212Mb)

OKLAHOMA'S UNITED STATES HOUSE DELEGATION AND PROGRESSIVISM, 1901-1917 By GEORGE O. CARNE~ // . Bachelor of Arts Central Missouri State College Warrensburg, Missouri 1964 Master of Arts Central Missouri State College Warrensburg, Missouri 1965 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 1972 OKLAHOMA STATE UNiVERSITY LIBRARY MAY 30 1973 ::.a-:r...... ... ~·· .. , .• ··~.• .. ,..,,.·· ,,.,., OKLAHOMA'S UNITED STATES HOUSE DELEGATION AND PROGRESSIVIS~, 1901-1917 Thesis Approved: Oean of the Graduate College PREFACE This dissertation is a study for a single state, Oklahoma, and is designed to test the prevailing Mowry-Chandler-Hofstadter thesis concerning progressivism. The "progressive profile" as developed in the Mowry-Chandler-Hofstadter thesis characterizes the progressive as one who possessed distinctive social, economic, and political qualities that distinguished him from the non-progressive. In 1965 in a political history seminar at Central Missouri State College, Warrensburg, Missouri, I tested the above model by using a single United States House representative from the state of Missouri. When I came to the Oklahoma State University in 1967, I decided to expand my test of this model by examining the thirteen representatives from Oklahoma during the years 1901 through 1917. In testing the thesis for Oklahoma, I investigated the social, economic, and political characteristics of the members whom Oklahoma sent to the United States House of Representatives during those years, and scrutinized the role they played in the formulation of domestic policy. In addition, a geographical analysis of the various Congressional districts suggested the effects the characteristics of the constituents might have on the representatives. -

Historic Resource Study

Historic Resource Study Minidoka Internment National Monument _____________________________________________________ Prepared for the National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Seattle, Washington Minidoka Internment National Monument Historic Resource Study Amy Lowe Meger History Department Colorado State University National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Seattle, Washington 2005 Table of Contents Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………… i Note on Terminology………………………………………….…………………..…. ii List of Figures ………………………………………………………………………. iii Part One - Before World War II Chapter One - Introduction - Minidoka Internment National Monument …………... 1 Chapter Two - Life on the Margins - History of Early Idaho………………………… 5 Chapter Three - Gardening in a Desert - Settlement and Development……………… 21 Chapter Four - Legalized Discrimination - Nikkei Before World War II……………. 37 Part Two - World War II Chapter Five- Outcry for Relocation - World War II in America ………….…..…… 65 Chapter Six - A Dust Covered Pseudo City - Camp Construction……………………. 87 Chapter Seven - Camp Minidoka - Evacuation, Relocation, and Incarceration ………105 Part Three - After World War II Chapter Eight - Farm in a Day- Settlement and Development Resume……………… 153 Chapter Nine - Conclusion- Commemoration and Memory………………………….. 163 Appendixes ………………………………………………………………………… 173 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………. 181 Cover: Nikkei working on canal drop at Minidoka, date and photographer unknown, circa 1943. (Minidoka Manuscript Collection, Hagerman Fossil -

The Progressive Era, 1900-1920

AP U.S. History: Unit 7.2 Student Edition The Progressive Era, 1900-1920 I. Road to Progressivism Use space below for notes A. The Greenback Labor Party of the 1870s sought to thwart the power of the "robber barons," support organized labor, and institute inflationary monetary measures. Supported primarily by farmers B. Legacy of Populism 1. Populism failed as a third-party cause but it had political influence for 25 years after its failure in the 1896 election. 2. Populist ideas that carried forward: a. railroad legislation (1903 & 1906) b. income tax (16th Amendment, 1912) c. expanded currency and credit structure (1913, 1916) d. direct election of senators (17th Amendment, 1913) e. initiative, referendum and recall (early 1900s in certain states) f. postal savings banks (1910) g. subtreasury plan (1916) 3. Though Populism was geared to rural life, many of its ideas appealed to urban progressives who sought to regulate trusts, reduce political machine influence, and remedy social injustice. POPULISM PROGRESSIVISM NEW DEAL (1890-1896) (1900-1920) (1933-1938) II. Rise of Progressivism th A. Former Mugwumps (reform-minded Republicans of the late-19 century) desired a return to pre-monopoly America. 1. Men of wealth and social standing lamented the changes in America’s political and social climate due to the rise of industrialists: monopoly, plutocracy and oligarchy. a. Protestant/Victorian ideals of hard work and morality leading to success were now threatened by the “nouveau riche,” the super wealthy, who seemed to thrive on conspicuous consumption. b. Earlier Mugwump leaders of local communities were now eclipsed by political machines catering to big business and immigrants. -

Jewel Cave National Monument Historic Resource Study

PLACE OF PASSAGES: JEWEL CAVE NATIONAL MONUMENT HISTORIC RESOURCE STUDY 2006 by Gail Evans-Hatch and Michael Evans-Hatch Evans-Hatch & Associates Published by Midwestern Region National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska _________________________________ i _________________________________ ii _________________________________ iii _________________________________ iv Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1: First Residents 7 Introduction Paleo-Indian Archaic Protohistoric Europeans Rock Art Lakota Lakota Spiritual Connection to the Black Hills Chapter 2: Exploration and Gold Discovery 33 Introduction The First Europeans United States Exploration The Lure of Gold Gold Attracts Euro-Americans to Sioux Land Creation of the Great Sioux Reservation Pressure Mounts for Euro-American Entry Economic Depression Heightens Clamor for Gold Custer’s 1874 Expedition Gordon Party & Gold-Seekers Arrive in Black Hills Chapter 3: Euro-Americans Come To Stay: Indians Dispossessed 59 Introduction Prospector Felix Michaud Arrives in the Black Hills Birth of Custer and Other Mining Camps Negotiating a New Treaty with the Sioux Gold Rush Bust Social and Cultural Landscape of Custer City and County Geographic Patterns of Early Mining Settlements Roads into the Black Hills Chapter 4: Establishing Roots: Harvesting Resources 93 Introduction Milling Lumber for Homes, Mines, and Farms Farming Railroads Arrive in the Black Hills Fluctuating Cycles in Agriculture Ranching Rancher Felix Michaud Harvesting Timber Fires in the Forest Landscapes of Diversifying Uses _________________________________ v Chapter 5: Jewel Cave: Discovery and Development 117 Introduction Conservation Policies Reach the Black Hills Jewel Cave Discovered Jewel Cave Development The Legal Environment Developing Jewel Cave to Attract Visitors The Wind Cave Example Michauds’ Continued Struggle Chapter 6: Jewel Cave Under the U.S. -

Political, Bureaucratic and Class Dynamics in a Growth Economy

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 12-28-2001 Water policy and theoretical models: Political, bureaucratic and class dynamics in a growth economy Kelly Michelle De Vine University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation De Vine, Kelly Michelle, "Water policy and theoretical models: Political, bureaucratic and class dynamics in a growth economy" (2001). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 3149. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/f6mc-8x2m This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter &ce, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent npon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

Roosevelt Becomes a Progressive Leader

ROOSEVELT BECOMES A PROGRESSIVE LEADER Directions: Read the two articles about Roosevelt and answer the questions which follow. Roosevelt the Progressive Theodore Roosevelt, a Harvard graduate and Conservationist, was viewed as the most important representative of Progressivism. He came to people’s attention at the time of the Spanish-American War. His courageous charge up San Juan Hill during that war made him a hero. Roosevelt was elected Republican governor of New York, partly through the efforts of Senator Thomas C. Platt. Platt was the Republican boss of New York State who thought that Roosevelt could help his business interests. However, Roosevelt had no intention of serving Platt’s interests. He attacked the ties between business and government and refused to appoint Platt’s choice for state insurance commissioner. To get Roosevelt out of the governorship, the Republican party nominated him as Vice-President to run with William McKinley. The VP was considered a dead end job; but when McKinley was assassinated in 1901, Roosevelt became President. Roosevelt was an active and strong President. He believed that the Federal Government should become involved when states were unable to deal with problems. He also believed the President should help shape legislative policy. Roosevelt promised farmers, workers, and small business people a “square deal.” When a 1902 coal strike could not be resolved, Roosevelt appointed a commission to make recommendations for settling the strike. For the first time, the federal government intervened in a strike in order to protect the public welfare. Roosevelt worked to curb trusts when they became harmful to the public interest. -

Historical Society Quarterly, 40:1 (Spring 1997), 28, 33, Fig

HistoricalNevada Society Quarterly John B. Reid Hillary Velázquez Juliet S. Pierson Editor-in-Chief & Frank Ozaki Manuscript Editor Production & Design Joyce M. Cox Proofreader Volume 56 Spring/Summer 2013 Numbers 1-2 Contents 3 Editor’s Note 7 Geologic Sources of Obsidian Artifacts from Spirit Cave, Nevada RICHARD E. HUGHES 14 Salmon’s Presence in Nevada’s Past ALISSA PRAGGASTIS AND JACK E. WILLIAMS 33 Mabel Wright and the Prayer that Saved Cui-ui Pah (Pyramid Lake) MICHAEL HITTMAN Front Cover: Katie Frazier, a Pauite, prepares cui-ui fish at Pyramid Lake, ca. 1930. Photographer unknown. (Nevada Historical Society) 76 Wovoka and the 1890 Ghost Dance Religion Q & A with Gunard Solberg MICHAEL HITTMAN 93 Cumulative Index – Volume 55 3 Editor’s Note My beautiful Lake— Used to be full, Just plumb full! Long time ago Lots of fishes… Mabel Wright’s protest prayer-song begins with these words. Sung in May 1964 on the south beach of Pyramid Lake, and accompanied only by a drum, Wright’s song called upon the traditional Paiute power of the spoken word to evoke the lake’s past and to protest threats to its survival. She chose a perfect location. From there, she could view the shoreline and hills where Wizards Beach Man lived more than 9,000 years ago and where fishing tools—a hook, a line made from sagebrush, and a sinker—were found and dated to 9,600 years ago. She could see the place where Sarah Winnemucca—Nevada’s greatest advocate for Native American rights—was born and lived her early years. -

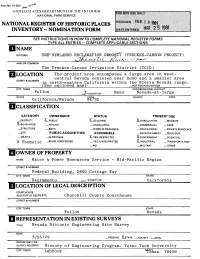

National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 ^e>J-, AO-"1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS THE^-NEWLANDS RECLAMATION Pft9«JE T (TRUCKEE-CARSON PROJECT) AND/OR COMMON The Truckee-Carson Irrigation District (TCID) LOCATION The project area encompases a large area in west- central Nevada centered near Reno and a smaller area STREET & NUMBER in north-eastern California within the Sierra Nevada range (See enclosed map) NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Fallen X VICINITY OF Reno Nevada-at-large STATE COUNTY CODE California/Nevada CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT X-PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED X.AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X_YES: RESTRICTED X.GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC X Thematic —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED XJNDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Water & Power Resources Service - Mid-Pacific Region STREET & NUMBER Federal Building, 2800 Cottage Way CITY, TOWN STATE Sacramento VICINITY OF California LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Churchill County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Nevada REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Nevada Historic Engineering Site Survey DATE 3725779 FEDERAL X.STATE COUNTY LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS History of Engineering Program. Texas Tech University CITY, TOWN Lubbock 79409 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_QRIGINALSITE .XGOOD —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE____ —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The theme of this nomination is Conservation. -

The Precedent of a President: Theodore Roosevelt and Environmental Conservation

Sigma: Journal of Political and International Studies Volume 22 Article 6 12-1-2004 The Precedent of a President: Theodore Roosevelt and Environmental Conservation Hilary Jan Izatt Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sigma Recommended Citation Izatt, Hilary Jan (2004) "The Precedent of a President: Theodore Roosevelt and Environmental Conservation," Sigma: Journal of Political and International Studies: Vol. 22 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sigma/vol22/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sigma: Journal of Political and International Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE PRECEDENT OF A PRESIDENT: Theodore Roosevelt and Environmental Conservation Hilary Jan Izatt ABSTRACT Thr legacy olPrrsident Theodor{' RooselJ('lt is one ofexpansion and great political prowess. Rooselielt's characteristic /ligor allowed him to pursue even the most obscure issues in the realm of politics. BeCllllS{, the president had a firm cOnlJiction concerning the cause of conser1'atioll, he managed to C01llH')' its importtUw' and bring it out olobscuri~y. Though Rooseuelt used every pr{'sidential role to filYt},er his enl'iromnental policies, the most important to him were the expanding roles ofchief exec utive and legislati/J(" leader. W'hile conserlJation was uirtual{y unknown to presidents before Roosevelt, it became (/ matter pertinent to the presidential (lgendas that followed. hen President William McKinley was assassinated in 1901, the nation was unsure W of the role the succeeding president would pursue. -

To America: Personal Reflections of an Historian Study Guide

To America: Personal Reflections of an Historian Study Guide Name ____________________________ To America: Personal Reflections of an Historian Stephen Ambrose is a world renowned historian and writer. He was chosen by President Eisenhower to be his personal biographer: Eisenhower: Soldier, General of the Army, President- Elect (1890 – 1952); Eisenhower, The President; The Supreme Commander: The War Years of General Dwight D Eisenhower; Eisenhower and Berlin, 1945 & Ike’s Spies. In addition he has written several pieces about WWII, my favorites were Pegasus Bridge, Band of Brothers and The Wild Blue. He has also researched and written about 25 other books about the Construction of the Transcontinental Railroad, the Lewis and Clark trek across the west, and the Nixon Presidency and more. His work is highly researched and documented; it is presented in a manner that is appealing; Stephen Ambrose has the gift of Storytelling. To America is an interesting culmination of all of his research and writing, but under review. In this love letter to America Ambrose takes us on a journey of reflection. While many of his books discuss an event, his focus is on the humans who made it happen. Reviewing his earlier perspectives of the lives of our national heroes and to some degree villains, in the end he determines that most were men, humans - great humans who under some circumstances make mistakes, use poor judgment, however that should not necessarily summarily remove them from study. Read Ambrose’s arguments and then formulate your own thoughts. We will be discussing each of the chapters in small groups and full class. -

JB APUSH Unit VIIA

ProgressivismProgressivism Progressive Political Reform Direct Democracy ▶ Secret ballots (Australian ballot) . All candidates printed on ballots . Vote in privacy at assigned polling place ▶ Direct primaries ▶ Government of the People . Initiatives ▶ Petition of enough voter signatures to force an election . Referendums ▶ Legislative proposals determined by electorate . Recalls ▶ Remove elected officials through local/state elections Seventeenth Amendment (1913) ▶ Problems . State legislature corruption ▶ Candidates bribed state legislators for votes . Electoral deadlocks ▶ State legislators could not agree on a selection leaving vacant seats ▶ Direct Election of Senators Progressive Political Reform Local/Municipalities ▶ Assert more control and regulation of public utilities and services . Built public parks and playgrounds, sanitation services, municipal services, public schools . Zoning laws (industrial, commercial, residential) ▶ Local Governments . Galveston Plan ▶ Commissioners and councils directly elected . Dayton Plan ▶ City managers hired as non-partisan Lincoln Steffens administrators The Shame of the Cities Inspired social and municipal reform Progressive Political Reform States ▶ Reforms ▶ “Wisconsin Idea” . Direct primaries . Robert LaFollette . Business regulations . Influence and Application . Tax reforms of Education on Politics . Suffrage ▶ Primary elections . Temperance ▶ Progressive taxes ▶ Workers’ compensation . State wages ▶ Regulation of railroads . Insurance plans ▶ Limit or eliminate monopolies . Child labor -

American History (AP)

American History (AP) COURSE OVERVIEW This yearling course is divided into four quarters consisting of a total of forty-two chapters broken down into sub-sections (units) ranging from two to three “subunits” per Unit. Each unit is then tested over using approximately one-hundred multiple-choice questions, a group of thirty to forty matching (People/Places and Events), a group of three to five identifications and a choice of one of three “thematic essay” questions. Each unit is introduced with a summary and listing of “People, Places and Events” relevant to that specific unit, these are to be defined and turned in on the day of the unit test. In addition, each student is divided into a study group that is responsible for the “Readings List” for classroom discussions, debates and written assignments. Students are also assigned a DBQ question that pertains to each individual unit. Primary Textbook Information: Kennedy, Cohen and Bailey (Advanced Placement Edition) The American Pageant, Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Company: copyright 2006 Supplemental Textbook Resources: Out of Many, A History of the American People: Faragher, Bulhe, Czitrorm & Armitage America, Pathways To the Present: Clayton, Perry, Reed, Winkler United States History: Preparing For The Advanced Placement Examination Primary Sources: Various primary sources are used throughout this course including, but not intended as an inclusive list below Carl J. Guarneri, America Compared, Second Edition, Vol., I & II. Kennedy & Bailey, The American Spirit, Eleventh Edution, Vol., I & II. Summer Readings John Lewis Graddis, The Cold War (A New History) Penguin Books 2005 Newman & Schmalbach, United StatesHhistory (Preparing for the Advanced Placement Examination) Amsco Publication, 2004 - Assorted reading sections, vocabulary, and essay questions.