Pospisil DP Finalni

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Issues in Ballads and Songs, Edited by Matilda Burden

SOCIAL ISSUES IN BALLADS AND SONGS Edited by MATILDA BURDEN Kommission für Volksdichtung Special Publications SOCIAL ISSUES IN BALLADS AND SONGS Social Issues in Ballads and Songs Edited by MATILDA BURDEN STELLENBOSCH KOMMISSION FÜR VOLKSDICHTUNG 2020 Kommission für Volksdichtung Special Publications Copyright © Matilda Burden and contributors, 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. Peer-review statement All papers have been subject to double-blind review by two referees. Editorial Board for this volume Ingrid Åkesson (Sweden) David Atkinson (England) Cozette Griffin-Kremer (France) Éva Guillorel (France) Sabina Ispas (Romania) Christine James (Wales) Thomas A. McKean (Scotland) Gerald Porter (Finland) Andy Rouse (Hungary) Evelyn Birge Vitz (USA) Online citations accessed and verified 25 September 2020. Contents xxx Introduction 1 Matilda Burden Beaten or Burned at the Stake: Structural, Gendered, and 4 Honour-Related Violence in Ballads Ingrid Åkesson The Social Dilemmas of ‘Daantjie Okso’: Texture, Text, and 21 Context Matilda Burden ‘Tlačanova voliča’ (‘The Peasant’s Oxen’): A Social and 34 Speciesist Ballad Marjetka Golež Kaučič From Textual to Cultural Meaning: ‘Tjanne’/‘Barbel’ in 51 Contextual Perspective Isabelle Peere Sin, Slaughter, and Sexuality: Clamour against Women Child- 87 Murderers by Irish Singers of ‘The Cruel Mother’ Gerald Porter Separation and Loss: An Attachment Theory Approach to 100 Emotions in Three Traditional French Chansons Evelyn Birge Vitz ‘Nobody loves me but my mother, and she could be jivin’ too’: 116 The Blues-Like Sentiment of Hip Hop Ballads Salim Washington Introduction Matilda Burden As the 43rd International Ballad Conference of the Kommission für Volksdichtung was the very first one ever to be held in the Southern Hemisphere, an opportunity arose to play with the letter ‘S’ in the conference theme. -

Introduction: Virginity and Patrilinear Legitimacy 1

Notes Introduction: Virginity and Patrilinear Legitimacy 1. Boswell, volume III, 406. 2. Pregnancy makes sex more verifiable than celibacy but it does not necessarily reveal paternity. 3. Bruce Boehrer has an important essay on this topic, in which he argues that an ideal “wedded chastity” emerges as a strategy for promoting marriage and procreation in a society that has traditionally idealized celibacy and virginity; “indeed,” he continues, “at heart the concept of wedded chastity is little more than the willful destabi- lizing of an inconvenient signifier, calculated to serve the procreative demands of an emergent political economy” (557). 4. For an important discussion of divine right of kings, see Figgis, 137–177, and for an analysis of the different strands of patriarchalist thought, see Schochet, 1–18. 5. See Boehrer for a discussion of Elizabeth’s legitimacy issues, which he uses as a context for reading Spencer. He argues that a “Legend of Chastity” functions as a displacement of the anxiety of legitimacy (566). On Elizabeth’s virginity, see also Hackett; and John King. On early modern virginity generally, see Jankowski; Kathleen Coyne Kelly; Loughlin; Scholz; and Schwarz. 6. Marie Loughlin argues for the relationship between Stuart political projects and virginity. James I had a habit of visiting married couples after the wedding night because, according to Loughlin, in the moment when the virgin daughter becomes the chaste bride “James’s configuration of the patriarchal state and his various political projects are materialized” (1996), 847. 7. For more on this, see McKeon (1987), 209. 8. Since the determination of firstborn son was not clear, firstborn ille- gitimate children often held some stake to the birth-right of the heir. -

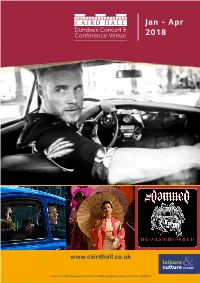

Jan - Apr 2018

Jan - Apr 2018 www.cairdhall.co.uk Leisure & Culture Dundee is a Scottish Charitable Incorporated Organisation No. SC042421 DIARY OF EVENTS January 2018 page Saturday 13 Mohsen Amini and Craig Irving 18 Sunday 14 Jean Johnson, Naomi and Fali Pavri 19 Wednesday 24 ELO Experience 4 Friday 26 Some Guys have All The Luck 4 Saturday 27 The Damned 5 Sunday 28 Mary McInroy 18 February 2018 Thursday 1 Steven Osborne Piano Recital 6 Friday 2 Erasure - SOLD OUT 6 Sunday 4 CD & Records Fair 19 Saturday 10 The Big Dundee Wedding Exhibition 7 Sunday 11 The Big Dundee Wedding Exhibition 7 Thursday 15 RSNO - Brief Encounter Live 7 Friday 23 Scottish National Jazz Orchestra 8 Saturday 24 The Elvis Years 9 Sunday 25 Dundee Gaelic Choir 18 March 2018 Saturday 3 Children's Classic Concerts - Tartan Tales 9 Sunday 4 CD & Records Fair 19 Wednesday 14 Rock Challenge Heats 10 Thursday 15 RSNO - Søndergård Conducts Ein Heldenleben 10 Friday 16 Scottish Ensemble - Court & Country 11 Sunday 18 Dundee Choral Union 11 Thursday 22 The Castalian Quartet 19 Friday 23 Big Girls Don’t Cry 12 Sunday 25 Dundee University Music Society 12 Tuesday 27 High School of Dundee Spring Concert 14 Friday 30 Rumours of Fleetwood Mac 13 Saturday 31 Dundee Symphony Orchestra 14 Kenzie Photography Kenzie April 2018 c Sunday 1 Madama Butterfly 15 ©James M Thursday 12 The Chicago Blues Brothers 16 Friday 20 Gary Barlow - SOLD OUT 16 Saturday 28 Seven Drunken Nights - The Story of the Dubliners 17 2 www.dundeebox.co.uk dundee city box office 01382434940 WELCOME Spring is in the air and with it, a packed brochure of Concerts some new, some sold out and some returning favourites. -

Download PDF Booklet

LIZZIE HIGGINS UP AND AWA’ WI’ THE LAVEROCK 1 Up and Awa Wi’ the Laverock 2 Lord Lovat 3 Soo Sewin’ Silk 4 Lady Mary Ann 5 MacDonald of Glencoe 6 The Forester 7 Tammy Toddles 8 Aul’ Roguie Gray 9 The Twa Brothers 10 The Cruel Mother 11 The Lassie Gathering Nuts First published by Topic 1975 Recorded and produced by Tony Engle, Aberdeen, January 1975 Notes by Peter Hall Sleeve design by Tony Engle Photographs by Peter Hall and Popperfoto Topic would like to thank Peter Hall for his help in making this record. This is the second solo record featuring the singing of Lizzie The Singer Higgins, one of our finest traditional singers, now at the height Good traditional singers depend to a considerable extent upon of her powers. The north-east of Scotland has been known for their background to equip them with the necessary artistic 200 years as a region rich in tradition, and recent collecting experience and skill, accumulated by preceding generations. has shown this still to be the case. Lizzie features on this It is not surprising then to find in Lizzie Higgins a superb record some of the big ballads for which the area is famed, exponent of Scots folk song, for she has all the advantages of such as The Twa Brothers, The Cruel Mother and The Forester. being born in the right region, the right community and, Like her famous mother, the late Jeannie Robertson, she has most important of all, the right family. The singing of her the grandeur to give these pieces their full majestic impact. -

Princes Theatre Princes Theatre

PRINCES THEATRE TOWN HALL, CLACTON-ON-SEA WHAT’S ON GUIDE SPRING 2017 WELCOME... Firstly, I would like to take this opportunity If you enjoyed Irelands Call and Essence For the family we are looking forward to a to wish all our customers a very Happy New of Ireland then Seven Drunken Nights is brand new show Marty MacDonald’s Toy Year and welcome you to another fantastic the show for you. Produced by the same Machine which is a fun, interactive, song- season at the Princes Theatre! production company Seven Drunken Nights filled adventure, featuring a host of lovable We didn’t think it was possible to top brings to life the music of puppet characters plus CBeebies’ Justin the success of 2015 but wow what a Ireland’s favourite sons – Fletcher is the voice of Pongo the Pig. phenomenal year 2016 turned out to be. ‘The Dubliners’. We finish off the season with a We had an impressive 130 shows/events Following his successful tour family extravaganza, this year’s Easter during the year including our first ever from last year we are pleased Pantomime Robin Hood starring Gareth Monsters Ball which was a huge success. to have back by popular demand Pasha Gates, Graham Cole and Zippy and George We also held 4 Boxing Events, 2 Wedding whose special guest is Anya Garnis with from children’s television show Rainbow. If Fairs, 5 Weddings and 3 award ceremonies. their brand new tour “Let’s Dance the Night you came to see last year’s Beauty and the The continuous growth of our theatre has Beast you know you will be in for a real treat. -

Greenshow After Dark 2019

Fathom the Bowl [C]Come all ye bold fellows that have to this place come And we'll [G]sing in the praise of good [D]brandy and [G]rum Let's [C]lift up our [F]glasses Good [D]cheer is our [G]goal Bring [C]in the punch [F]ladle and we'll [G]fathom the [C]bowl Fathom the bowl [F]Fathom the [G]bowl Bring [C]in the punch [F]ladle and we'll [G]fathom the [C]bowl [C]From France we do get brandy, Jamaica comes rum Sweet [G]oranges and lemons from [D]Portugal [G]come But [C]stout beer and [F]cider Is [D]England's [G]control Bring [C]in the punch [F]ladle and we'll [G]fathom the [C]bowl Fathom the bowl [F]Fathom the [G]bowl Bring [C]in the punch [F]ladle and we'll [G]fathom the [C]bowl [C]O my father, he do lie in the depths of the sea With no [G]stone at his feet but what [D]matter for [G]he? There's a [C]clear crystal [F]fountain Near [D]England doth [G]roll Bring [C]in the punch [F]ladle and we'll [G]fathom the [C]bowl Fathom the bowl [F]Fathom the [G]bowl Bring [C]in the punch [F]ladle and we'll [G]fathom the [C]bowl Fathom the bowl [F]Fathom the [G]bowl Bring [C]in the punch [F]ladle and we'll [G]fathom the [C]bowl [NO CHORDS] Fathom the bowl Fathom the bowl Bring in the punch ladle and we'll fathom the bowl [C] The Girls of Dublin Town Well, the [E]Shenandoah was a good ship, mates From [B]Dublin town she came And the [A]captain being an [E]Irishman And [B]Murphy [A]was his [E]name 'Twas on the 17th of March We lay in Mobile Bay And the captain being an Irishman Did celebrate the day The crew, all being union men Who came from Dublin town -

A City out of Old Songs

A City Out of Old Songs: The influence of ballads, hymns and children’s songs on an Irish writer and broadcaster Catherine Ann Cullen Context Statement for PhD by Public Works Middlesex University Director of Studies: Dr Maggie Butt Co-Supervisor: Dr Lorna Gibb Contents: Public Works Presented as Part 1 of this PhD ............................................................ iii List of Illustrations ....................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................... v Preface: Come, Gather Round ..................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Singing Without Ceasing .................................................................... 8 Chapter 2: A Tune That Could Calm Any Storm ......................................................... 23 Chapter 3: Something Rich and Strange .................................................................... 47 Chapter 4: We Weave a Song Beneath Our Skins ...................................................... 66 Chapter 5: To Hear the Nightingale Sing ................................................................... 98 Conclusion: All Past Reflections Shimmer into One ............................................... 108 Works Cited .............................................................................................................. 112 Appendix 1: Index of Ballads and Songs used -

“Pile High the Pennywall” 1. Darker Than The

“Pile High the Pennywall” 1. Darker Than the Mine (M. Sisti) 2. Pennywall (A. Sisti, M. Sisti) 3. The Apparatus (M. Sisti) 4. Stolen Child (M. Sisti) 5. Share the Wealth (S. Hawley) 6. The Ballad of Angus Kerry (M. Sisti, A. Sisti, G. Voce) 7. I Don’t Want To See Her Tonight (D. Sisti, M. Sisti) 8. River of Questions and Time (M. Sisti) 9. Mama Knows Best (A. Sisti) 10. Love Lost (M. Sisti) 11. Clarion Call (A. Sisti, M. Sisti) 12. Take It From Me (D. Sisti, M. Sisti) 13. Everyone Loves You When You’re Dead (M. Sisti) DARKER THAN THE MINE (M. Sisti) PENNYWALL (A. Sisti, M. Sisti) I worked the mines alongside of dad from the day that I turned ten So cold, in the home that my father built, alongside his father Dawn to dusk for a dollar a week turns young boys into men I’m told that the land that we’ve labored on is gone with the stroke of a pen The cold and damp would chill your bones, the dust would fill your lungs And with no food fit to place on my table, Men never lived till they grew old, they died while they were young I don’t think we’ll see a new day But the mine boss didn’t care at all, it was all just bottom line Then the man called out to all who were able He had a heart as black as coal, it was darker than the mine “Move the stones from this land, Build a wall long and grand, Darker than the mine, darker than the mine And we’ll pay you a penny a day.” He had a heart as black as coal that was darker than the mine Pile high the Pennywall Pennies a day keeps the hunger at bay, so I… Then one day the methane blew and crushed young Tim McBride Pile high the Pennywall Rocks blocked the only entrance trapping him inside So empty inside that I swallow my pride, But no exit tunnel had been built, no way he could get out. -

Fall 2012 English & Creative Writing Courses

Fall 2012 English & Creative Writing Courses BEFORE THE MAJOR/NON-MAJOR COURSES ENGL 190: Harry Potter Section 1: MWF 12:00-12:50 PM Dr. Ward ENGL 190: Sex, God, and Guns: Ireland in Literature, Film, and Song Section 2: TR 1:40-2:55 PM [RSS 235] Dr. Kelly Books: Dubliners, James Joyce The Concise History of Ireland, Sean Duffy Modern and Contemporary Irish Drama, Harrington, ed. The Snapper, Roddy Doyle Movies: Michael Collins, Neal Jordan, director The Informer, John Ford, director The Quiet Man, John Ford, director The Crying Game, Neal Jordan, director The Snapper, Stephen Frears, director Music: The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem Live at Carnegie Hall The Dubliners “Seven Drunken Nights,” “Monto,” “Rising of the Moon,” “Dirty Old Town,” “The Town I Loved So Well,” “Raglan Road,” “The Fields of Athenry,” “Gentleman Soldier,” “Foggy Dew” U2 War The Pogues The Very Best of the Pogues .pdfs Yeats, “Easter 1916” and “September 1913” Joyce, “Telemachus” O’Connor, “Guests of the Nation” Kavanagh, “The Great Hunger” O’Brien, The Country Girls ENGL 190: Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials and the Power of Story Section 3: TR 12:15-1:30 PM Dr. Birrer In this class, we’ll study Philip Pullman’s award-winning contemporary fantasy trilogy His Dark Materials as a way to explore the power of stories to shape human experience, both for good and for ill. We’ll analyze how Pullman’s fictional stories draw on, challenge, and otherwise re-imagine earlier fantasy tales and other literary texts, including Lewis’ Narnia Chronicles, Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, a few pretty fantastic snippets about Satan from Paradise Lost, some wild tales about Adam and Eve that didn’t quite make the Bible, and a strange little text about marionettes and fencing bears. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Singing the Child Ballads

Singing the Child Ballads In this column Rosaleen Gregory continues her composite, said to be collected from “various journey through the Child ballads in her own sources”. The tune is from Alexander Keith’s repertoire, and calls for readers’ submissions of selection from Gavin Greig’s collecting, Last alternative versions that they sing, or of other ballads Leaves of the Traditional Ballads and Ballad in the Child canon that she does not perform. This Airs (Aberdeen: The Buchan Club, 1925). time we cover Child Nos. 16-21. The Cruel Mother, # 20 Rosaleen writes: My version is called “Down by the Greenwood Sheath and Knife, # 16 Sidey”, and is mainly that noted by Robert and Henry Hammond from Mrs. Case, at Sydling St. Nicholas, The text I sing is Child’s version A, which was Dorset, in September 1907. The Hammonds collected reprinted from William Motherwell, ed., Minstrelsy two other versions of “The Cruel Mother” in Dorset Ancient and Modern (Glasgow: John Wylie, 1827). in 1907: one from Mrs. Russell at Upwey in The ballad was noted by Motherwell in February February, and the other from Mrs. Bowring at Cerne 1825 from an informant named Mrs. King, who lived Abbas in September. Milner and Kaplan appear to in the parish of Kilbarchan. The tune is from James have collated the text from these three (and perhaps Johnson, ed., The Scots Musical Museum, Consisting other) sources, and they took the tune from that of Six Hundred Scots Songs, 2 Vols. (Edinburgh: printed by Henry Hammond in the Journal of the James Johnson, 1787-1803).