Homophobia in Sport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Well Summer Final 2015.Pub

THE WELL Kemsing Village Magazine with news from Woodlands Summer 2015 No 198 See Centre pages for the Kemsing School Pool Big Splash! CONTENTS - The Well, Summer 2015 No 198 Tom Bosworth 3 Designs wanted for Christmas Cards 19 Vicar’s letter 4 Community Choir 21 Church Services 5 News from Cotmans Ash 23 Woodlands News 7 Design for Embroidery Workshop 24 News and Notes 9 Our new Kemsing Librarian 26 Parochial Church Council News 11 Family Milestones 28 Kemsing Parish Council News 13 25 & 50 Years Ago 28 Swimming Pool—Re-opening 15 Kemsing School Report 30 - and photographs 16/17 Village Diary 31 Noah’s Ark Footpaths 19 Editorial Team:- Doreen Farrow, Janet Eaton & Rosemary Banister We reserve the right to edit [i.e. cut, précis, alter, correct grammar or spelling] any item published, and our decision is final. Wild Flowers — Cover picture. Photograph by John Farrow COPY FOR NEXT ISSUE by 1st August 2015 THE WELL - is published and distributed free, four times a year by the Parochial Church Councils of St Mary’s Church, Kemsing and St Mary’s Church, Woodlands, to encourage and stimulate the life of the community. The views expressed in the magazine do not necessarily represent official church opinion or policy. If you use a computer to type your article, it would be extremely helpful if you could Email it to: [email protected] (PLEASE NOTE NEW EMAIL ADDRESS) or send to the Editors c/o Poppies Cottage, 3, St. Edith’s Road, Kemsing , Sevenoaks, Kent TN15 6PT. For postal subscriptions, contact Debby Pierson—01732 762033 2 KEMSING’S OWN CHAMPION—TOM BOSWORTH he 2015 athletics season has started as 2014 finished for Tom Bosworth, with a T British title and new British Record. -

Tom Bosworth

Record Tom Bosworth th Race Walking 6 at Rio Olympics in a new August 2016 British Record Race Walking Record – August 2016 Over the next two kilometres, Bosworth sped up and was within eight minutes for the next 2km split around the Pontal course. But Matsunaga was race walking even faster and had closed the gap to two seconds, while China’s Zelin Cai decided to protectively cover the two men in front of him and had pushed hard to remove himself from the pack. World Race Walking Team Championships silver medallist Cai continued to motor and overtook Matsunaga and then Bosworth but The XXXI Olympic Games, Rio De Janeiro, Brazil the pack also started to increase their pace, consuming Bosworth and Men’s 20km (Fri. 12th Aug.): Despite the presence of Olympic Matsunaga just before the 14km checkpoint and Cai shortly after, champion Chen Ding and world champion Miguel Angel Lopez, the making it a 12-man mass together entering the final quarter of the pre-race favourite on current form was China’s Wang Zhen and the race. winner at the IAAF World Race Walking Team Championships in The pack – which also contained local hope and Brazilian record- Rome back in May didn’t disappoint. holder Caio Bonfim, who was getting rousing cheers every step of the way – was reduced to nine over the next lap with Cai, whose cadence can best be described as a resembling a boxer doing his road workout, pushing the pace at the front. This remained the state of affairs until Wang, a much more fluent and elegant race walker than his teammate, made his decisive bid for glory with three kilometres to go. -

Heel and Toe 2015/2016 Number 25

HEEL AND TOE ONLINE The official organ of the Victorian Race Walking Club 2015/2016 Number 25 22 March 2016 VRWC Preferred Supplier of Shoes, clothes and sporting accessories. Address: RUNNERS WORLD, 598 High Street, East Kew, Victoria (Melways 45 G4) Telephone: 03 9817 3503 Hours: Monday to Friday: 9:30am to 5:30pm Saturday: 9:00am to 3:00pm Website: http://www.runnersworld.com.au Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/pages/Runners-World/235649459888840 WALKER OF THE WEEK With Little Athletics and Masters State Championships on offer as well as a number of overseas walks to consider, it was a tough ask to choose this week's Walker of the Week but I have decided in favour of 14 year old Ballarat walker Jemma Peart. Competing in the Little Athletics Victoria U15 1500m walk championship at the Casey Fields athletics track in Berwick (Melbourne) last weekend, she won in a huge time of 6:29.19, setting a new championship record and doing a 26 sec PB! Jemma showed her potential with a win in the 2015 LBG Carnival U14 2km walk last June (9:23) but it is this summer that she has really kicked down. She won the Victorian U16 3000m championship in 14:35 in February and then improved to 14:13 in taking third in the Australian U16 3000m in Perth in March (she also took bronze in the U18 5000m walk with 15:29 at these same Australian Championships). Cousins of international walkers Jared and Rachel Tallent, Jemma and her younger sister Alanna are the latest in a long line of talented walkers to come from the Victorian country city of Ballarat. -

London 2018: Flash Interviews (PDF)

IAAF DIAMOND LEAGUE London (GBR) 21st - 22nd July 2018 Flash Quotes TIMING, RESULTS SERVICE & DISTANCE MEASUREMENT BY Dwayne COWAN (GBR) 400m Men National - 1st (45.65 SB) Hopefully there is an individual spot left. I am happy with the race today. Martyn and I are quite similar at the moment. I've been injured all season, so hopefully I can finish the year off strongly. I love this stadium - I always run fast here. 21/07/2018 12:43 Martyn ROONEY (GBR) 400m Men National - 2nd (46.11) I have a bye as the defending champion so hopefully I'll be selected for Europeans. I thought the run was disappointing. I thought coming here I'd run a 45 second low time but it's just not happening. We'll wait and see what the championships bring, it's just about hard training between now and then. 21/07/2018 12:44 Tom BOSWORTH (GBR) 3000m Race Walk Men - 1st (10:43.9) PB, WR, WL It was a shock to do that. I've just come back from altitude training but I still wanted to see what I could do and this is all heading in the right direction for the Europeans. Coming to the London Stadium changes everything for me. Usually I'm on the road and race walking isn't included in the Diamond League very often. I thought there was going to be trouble if I got beaten but I knew the crowd would push me home in that world class field. He was fourth in London last year and I knew it was going to take a PB to win. -

Race Walking Record – July 2017

Record Tom Bosworth, smashed the world mile Race Walking walk record at the Müller July 2017 Anniversary Games in London Race Walking Record – July 2017 proudly presents its (also qualifying event for 2018 - IAAF World U20 Championships, IAAF World Team Championships, European Championships & European Youth Championships) st Sunday 1 October 2017 starting at 10:30am (Full timetable of events will be published closer to date of event once total number of entries known) Hillingdon Cycle Circuit, Minet Country Park, Springfield Road, Hayes, UB4 0LP (IAAF Measured Course – 1km Flat Loop) 20km/10km/U17 5km/U15 3km/U13 2km (to be held in accordance with UKA Rules of Competition and to be judged in accordance with IAAF Rules) Entry Fees: 20km/10km = £10.00. All other events = £7.00 Entering Entry fees as shown above Post completed form & fee Email completed form and pay online to [email protected] to Noel Carmody – 41 Herbert Road, Pay online: Barclays Bexleyheath, Kent, DA7 4QF. Sort Code 20-62-69 – Acc. 60780391 Cheques payable to Race Walking Association Show Reference as Surname + Post Code Closing date for entries = Tuesday 26th September 2017 (Entry forms available from Noel Carmody ([email protected] ) or Facebook - https://www.facebook.com/groups/139423539480219/ Editor: Noel Carmody – Email: noel.carmod [email protected] Race Walking Record – July 2017 determine whether there are sufficient numbers of athletes and countries legitimately interested.” The following five athletes have achieved performances within the published qualifying time. Perf Athlete Nation Venue Date 4:08:26 Ines Henriques POR Porto de Mos (POR) 15-Jan 4:22:22 Hang Yin CHN Huangshan (CHN) 05-Mar 4:26:37 Kathleen Burnett USA Santee (USA) 28-Jan 4:27:24 Shuging Yang CHN Huangshan (CHN) 05-Mar 4:29:33 Erin Taylor-Talcott USA Santee (USA) 28-Jan 29th July: Two more women added to the 50km as the IAAF’s own rules provide that an Area Champions, regardless of the time they post, are deemed to have achieved the entry standard. -

Emblem Simplified but Expressive, Say Football and Sports Officials in Qatar

Inspired Nadal storms into quarter-final at US Open PAGE 14 WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 4, 2019 Emblem simplified but expressive, say football and sports officials in Qatar TRIBUNE NEWS NETWORK Qatar’s vision of the World and appreciated the great ef- digital presentation. DOHA Cup and the importance of the forts made to highlight the Al Khulaifi stressed that Arab symbolism of the event. work, which is a clear and the launch of the logo is an ATAR’S local football Ballan added that the sustainable Qatari footprint important message for the and sports adminis- logo carried a great mean- in the history of football. peace-loving world. “The trators welcomed the ing from Qatar to the world Ali al Naimi, former vice- beautiful thing is that the Qlaunch of FIFA World through the Arab shawl, president of Al Rayyan club, world joins us in this excit- Cup 2022 Qatar em- which means more than the said that he is very proud of ing event, especially with blem on Tuesday which saw oriental inscriptions that the just unveiled emblem for the start of qualifying for the the world come aglow with the adorn the wool shawl. FIFA World Cup 2022 Qatar. World Cup 2022, which in- insignia at precisely 20:22hrs “Qatar with its creative He pointed out that the dicates the countdown to the Doha Time. touch in organising tourna- slogan of the World Cup is World Cup in Qatar.” Celebrating the occasion, ments can present the Arab linked to Qataris and the na- Also commending the Hani Talib Ballan, CEO of culture to the world through tional heritage. -

Issue No: 371 August/September 2016 Editor: Dave Ainsworth

Issue No: 371 August/September 2016 Editor: Dave Ainsworth AFTER 52 YEARS Not since Britain's greatest ever race walker, Ken Matthews MBE, struck gold at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics 20K has a British athlete won a World title. In July Enfield's Callum Wilkinson won the World Under-20 Championship 10,000 Metres in Poland clocking an excellent 40.41.62. He's rightly been showered with heaps of deserved praise and bombarded by congratulatory messages - and had a surprise celebration in his honour in Moulton Village Hall. Among admirers was Paula Radcliffe MBE, who tweeted "What a morning for the World Junior Champion, leading from 4K and smashing the last 2K". A STAR QUARTET We congratulate 4 race walking notables who'll be at the Rio Olympics. Tom Bosworth makes his Olympic debut at 20K, while Dominic King makes a 2nd Olympic 50K appearance. Many readers have seen them develop talents from their early days in our sport, and will be delighted they're on world's main sporting stage. Ilford AC life member, Neringa Aidietyte, is to make her second Olympic 20K appearance for Lithuania. Also in Rio is Peter Marlow, a former Olympic 20K walker himself (1972 Munich). Peter's again selected for the Judges' panel, proof of his high standing in International Athletics. In addition to those 4 mentioned, let's also note Chris Maddocks (5 times' Olympian) is again selected for commentary box duties. We wish them the best, and also all who'll be in Rio as supporters. ANNUAL 8-COUNTIES' REPRESENTATIVE MATCH We thank those who travelled to Basingstoke as Essex competitors in the annual 8-Counties' Representative Match (Essex/Hampshire/Hertfordshire/Kent/Middlesex/Oxfordshire/Surrey/Sussex). -

Heel and Toe 2019/2020 Number 23

HEEL AND TOE ONLINE The official organ of the Victorian Race Walking Club 2019/2020 Number 23 Tuesday 3 March 2020 VRWC Preferred Supplier of Shoes, clothes and sporting accessories. Address: RUNNERS WORLD, 598 High Street, East Kew, Victoria (Melways 45 G4) Telephone: 03 9817 3503 Hours: Monday to Friday: 9:30am to 5:30pm Saturday: 9:00am to 3:00pm Website: http://www.runnersworld.com.au Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/pages/Runners-World/235649459888840 IS THIS THE END OF THE ROAD FOR THE 50KM WALK? It’s not yet been released to the general public but a draft timetable for the 2021 World Athletics Championships, to be held in Eugene, Oregon, on 6-15 August 2021 shows that the 50km is to be replaced by a 35km walk. Here is the program cut and paste which shows the women’s 20km on Day 3, the men’s 20km on Day 4, the women’s 35km on Day 7 and the men’s 35km on Day 8. No consultation has been held with the wider walking community and, in my opinion, no proper analysis of the implications of this change have been done. My comments are as follows • This move is contrary to the press release issued by the IAAF at the Council meeting at Doha. That press release read Specifically it promised no changes until 2022 (see https://www.worldathletics.org/news/press-release/council-march- 2019-doha-race-walk-diamond-lea). As an aside, it also promised testing and validation of the electronic chip insole technology during competition in 2020. -

Tom Bosworth Callum Wilkinson

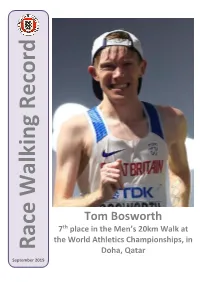

July 2019 Record Tom Bosworth Callum Wilkinson Tom Bosworth Cameron Corbishley Dominic King th 7 place in the Men’s 20km Walk at the World Athletics Championships, in Race Walking Doha, Qatar September 2019 Race Walking Record – September 2019 TARGETED EVENTS PROGRAMME RACE WALKING 2019-2020 Race Walk Training Camps • 17th November 2019 Sutcliffe Park Sports Centre, Eltham Road, London, SE9 5LW • 8th December 2019 Aldershot Military Stadium, Queen's Avenue, Aldershot, GU11 2JL th • 12 January 2020 Sutcliffe Park Sports Centre, Eltham Road, London, SE9 5LW • 17th-19th February 2020 Leeds Beckett University, Headingley Campus, Leeds, LS6 3QT Training days for invited athletes and coaches, from 10:00 -14:00 and largely practical in nature. They will focus on being the best athlete you can be from a technical, tactical, physical and mental perspective. To register, please email Andrew Drake, at [email protected] Invitation criteria: Athletes who competed in the 2019 ESAA Race Walking Championships; Athletes who competed in the 2019 EA U15/U17/U20/U23 Championships; Athletes who competed at 2019 British Trials - 5000m; Coach recommendations; Established endurance athletes who wish to try race walking. www.englandathletics.org Editor: Noel Carmody – Email: [email protected] Race Walking Record – September 2019 Women: Former world record-holder Rui Liang won in 4:23:26 ahead International Competition of her compatriot Maocuo Li in 4:26:40 and Italy’s European record- holder Eleonora Giorgi in 4:29:13. Portugal’s defending champion Ines Henriques was among those to drop out and Ukraine’s Olena Sobchuk claimed fourth place in 4:33:38. -

Leading Walkers from the First Virtual Enfield Race Walking League

Record Tom Bosworth Callum Wilkinson George Wilkinson Millie Morris Cameron Corbishley Dominic King Jacqueline Benson Jonathan Hobbs Race Walking Leading Walkers from the first Virtual Enfield Race Walking League January 2021 Photograph(s) courtesy of Mark Easton (http://markeaston.zenfolio.com) Race Walking Record – January 2021 Centurions 100 Mile Walk 2021 Centurions, subject to COVID-19 guidelines, are hopeful of staging a Olympic Games Trial for the 20km Race Walks to take place 100 mile track race at Southend in early August, (provisionally 7th & at Kew Gardens in March 8th). As the foreseeable future remains uncertain, they cannot give definite confirmation now, so please check their website for updates. 21st Jan: UK Athletics has confirmed that the Olympic Games Trial for the men’s and women’s 20km Race Walk will take place behind-closed- Adhering to the Government guidelines current at the time will be a doors on Friday 26th March 2021, at Kew Gardens, London, on the mandatory requirement for everybody attending – walkers, same day as the Olympic Games Marathon Trial. supporters, organisers, officials, and spectators – so the event may be slightly different to those held previously but they are committed to Following several postponements in the 2021 race walking calendar, providing everybody the opportunity to take part in this unique race. UK Athletics are providing this key competition opportunity for Olympic qualification following discussions with athletes and coaches. Source: www.centurions1911.org.uk The window for attaining a qualification standard for the 20km Race Walks will be remain open until 27th June 2021. National 10km & Young Age Group Entry will be by invitation only with very limited numbers, and the Championships 2021 men’s and women’s 20km Race Walks will be combined. -

COVERING LGBTQ ATHLETES at the 2020 OLYMPICS and PARALYMPICS a Resource for Journalists and Media Professionals CHAPTER GUIDE

COVERING LGBTQ ATHLETES AT THE 2020 OLYMPICS AND PARALYMPICS A resource for journalists and media professionals CHAPTER GUIDE 1| Introduction 3 2| Terminology Basics 4 3| Best Practices for Reporting on Transgender Athletes 6 4| Olympic Policies on the Inclusion of Transgender Athletes 7 5| Some LGBTQ Athletes to Watch 8 6| History of LGBTQ Athletes at the Olympics 11 7| SOGIESC Discrimination in Sports and a Rise in Anti-Trans Hate 12 8| Anti-LGBTQ+ Activists and Media Misinformation 15 9| Japanese Context 17 10| Japanese LGBTQ Advocacy Organizations 18 11 | LGBTQ+ Athletes in Japan 19 2 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION A record number of out LGBTQ athletes—at least 142 at the time of publication—are competing in the Tokyo Games from the U.S. and around the world1. LGBTQ athletes have likely competed in the Olympics and Paralympics since the very first Games in history. It’s only now that more are comfortable being out as their authentic selves, with many embraced and supported by fans and sponsors. The growing visibility and acceptance of out athletes offers a unique opportunity for global audiences to see LGBTQ people as individuals on the world stage. LGBTQ athletes have the same basic human need to belong and—with an elite athlete’s drive to achieve—to represent their respective countries with pride, support, and dignity. The Olympic and Paralympic Games are a celebration of our shared humanity and represent the pinnacle of sports achievement. Including LGBTQ athletes in your coverage means exploring all their challenges and triumphs, not just their sexual orientations, sex characteristics and gender identities. -

Tom Bosworth

English Schools Championships 2015 Tom Bosworth 24th in the Men’s 20km at the 15th IAAF World Athletics Championships in Beijing Record Intermediate Boys Podium Tom Partington ~ Chris Snook ~ Marshall Smith ~ Ollie Hopkins Race Walking Intermediate Girls Podium September 2015 Emily Ghose ~ Sophie Lewis Ward ~ Abigail Jennings ~ Indigo Burgin ~ Lucy Webster Race Walking Record – September 2015 Race Walking Association (Southern Area) Open to all first claim members of affiliated clubs within the South of England defined region The races will be held in accordance with UKA Rules of Competition and will be judged in accordance with IAAF Rule 230 The races to form the league will be: th Cambr idge Harriers Open Race Walks on Sat. 17 October 2015 SRWA Senior 10km & YAG Championships on Sat. 16th January 2016 th London Open Race Walks on Sun. 7 February 2016 (It had been hoped to have a fourth event in December 2015 but a suitable event could not be found) Individual Scoring Points will be awarded after each race on finishing position st nd rd (For example 1 = 40 points, 2 = 38, 3 = 37 and so on down to 1) The individual winners in each age group will be determined by the highest points total scored from two out of the three races. Team Scoring The winning team will be determined by the highest total of team points scored when adding all the points scored together of all participants from the same club across all age groups, scored from three out three races. For more information contact the SRWA Hon. Championship Sec retary Noel Carmody ([email protected]) Race Walking Record – September 2015 National 42nd English Schools Championships, Bedford (Sat 19th Sept.) Youth Development League Invitation Walks, The junior girls 3000m had an entry of sixteen with twelve starting.