Colony Hill Historic District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colony Hill Historic District Nomination

2 Name and telephone of author of application EHT Traceries, Inc. (202) 393-1199 Date received ___________ H.P.O. staff ___________ NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Colony Hill Historic District Other names/site number: N/A Name of related multiple property listing: N/A ___________________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: 1700-1731 Hoban Road, N.W., 1800-1821 Hoban Road, N.W., 4501-4520 Hoban Road, N.W., 1801-1820 Forty-Fifth Street, N.W., 4407-4444 Hadfield Road, N.W., 1701-1717 Foxhall Road, NW. City or town: Washington State: District of Columbia County: ____________ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

HPRB ACTIONS January 28 and February 4 2021.Pdf

GOVERNMENT OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA HISTORIC PRESERVATION REVIEW BOARD HPRB ACTIONS January 28 and February 4, 2021 The Historic Preservation Review Board convened a public meeting on January 28 and February 4 via WebEx. JANUARY 28 MEETING Present for the meeting were: Marnique Heath, Chair; Andrew Aurbach, Matthew Bell, Linda Greene, Outerbridge Horsey, Alexandra Jones, Sandra Jowers-Barber, Gretchen Pfaehler. AGENDA HISTORIC DISTRICT DESIGNATION HEARING Colony Hill Historic District, HP Case 21-03, encompassing Hoban Road NW (all addresses) Hadfield Lane NW (all addresses); 1800 block 45th Street NW (all addresses); and 1699, 1701, 1709, 1717 Foxhall Road NW. The Board voted 5-3 to not support the HPO staff report recommending that the Colony Hill neighborhood be designated as a historic district. However, following the vote, the Chair acknowledged that the Board had not followed its required procedures in that it had not addressed the designation criteria or the ANC resolution. Accordingly, the Chair asked that the case be continued to the February 4th meeting. CLEVELAND PARK HISTORIC DISTRICT 3000 Tilden Street NW (Tilden Gardens), HPA 21-052, permit/replace 1,483 windows. The Board voted to deny recommendation of approval of the permit for window replacement and recommended the applicant develop a preservation solution for more of the original windows. Vote: 8-0. WALTER REED HISTORIC DISTRICT 6900 Georgia Avenue NW, HPA 21-131, concept/new construction of five-story mixed use building. The Board expressed general support for the -

Washington DC Neighborhodd Trends Report 2013/14

CAPITAL 2013 /14’ MARKET WASHINGTON DC APPRAISAL NEIGHBORHOOD RESEARCH TRENDS DESK REPORT VOLUME 1, MARCH 2014 When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir. —John Maynard Keynes Contents 4 Introduction 4 Conventional, Conforming 30-Yr Fixed-Rate 4 Mortgage-Related Bond Issuance and Outstanding 6 The DC Market: One/ Five/ Ten-Year Relative Returns 7 DC Index vs. 10-City Composite Component Indices 7 Seasonality Index 7 Months of Inventory 10 Total Sales Volume and Financing Trends 11 Median Days on Market (DOM) 11 Distressed Sales 13 Parking 13 Market Value and Sales Volume 16 Washington DC: Neighborhood Trends 2013 16 Sales Volume Leaders 16 Market Cap Leaders 19 Median Sale Price 21 Median Sale to List Price 22 Median Days on Market 23 Distressed Sales 24 Neighborhood Databook 2013 30 Neighborhood Map 31 About Us 32 End Notes / General Disclaimer 1 202 320 3702 [email protected] 1125 11 St NW 402 WDC 20001 www.CapitalMarketAppraisal.com Introduction Mortgage-Related Bond Issuance and Outstanding he Capital Market Appraisal 2013 Neighborhood Trends Over the prior year residential mortgage-related bond is- Report was developed to provide market participants suance3 declined 7.6%, falling from $2.019 trillion in 2012 to with a comprehensive overview of the residential real $1.866 trillion in 2013. Over the same period of time resi- T 1 3 estate market in Washington, DC (DC Market ). dential mortgage-related bonds outstanding declined 1.04% from $8.179 trillion in 2012 to $8.094 trillion in 2013. As the We begin by highlighting a few broad measure—medium term overwhelming majority of residential mortgages are packaged trends in the mortgage market. -

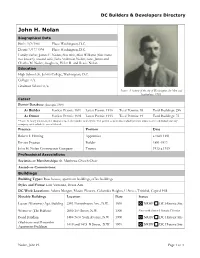

John H. Nolan

DC Builders & Developers Directory John H. Nolan Biographical Data Birth: 5/?/1861 Place: Washington, D.C. Death: 2/17/1924 Place: Washington, D.C. Family: father, James F. Nolan; first wife, Miss Williams (first name not known); second wife, Lida Anderson Nolan; sons, James and Charles M. Nolan; daughters, Helen R. and Bessie Nolan Education High School: St. John’s College, Washington, D.C. College: n/a Graduate School: n/a Source: A history of the city of Washington, Its Men and Institutions, 1903 Career Permit Database (through 1958) As Builder Earliest Permit: 1891 Latest Permit: 1916 Total Permits: 93 Total Buildings: 258 As Owner Earliest Permit: 1893 Latest Permit: 1913 Total Permits: 19 Total Buildings: 72 *Note: In many instances, the subject is both the builder and owner. The permit counts also include permits issues to the individual and any company with which he was affiliated. Practice Position Date Robert I. Fleming Apprentice c.1880-1891 Private Practice Builder 1891-1922 John H. Nolan Construction Company Trustee 1913-c.1919 Professional Associations Societies or Memberships: St. Matthews Church Choir Awards or Commissions: Buildings Building Types: Row houses, apartment buildings, office buildings Styles and Forms: Late Victorian, Beaux Arts DC Work Locations: Adams Morgan, Mount Pleasant, Columbia Heights, U Street, Trinidad, Capitol Hill Notable Buildings Location Date Status Luzon (Westover) Apt. Building 2501 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W. 1896 NRHP DC Historic Site Westover (The Balfour) 2000 16th Street, N.W. 1900 Sixteenth Street Historic District Bond Building 1404 New York Avenue, N.W. 1900 NRHP DC Historic Site Gladstone and Hawarden 1419 and 1423 R Street, N.W. -

Vermont Vacation

ROOMS FURN.—N.W. (Cont.) RMS., APTS. TO SHARE (Cost.) APTS. FURNISHED (Coot.) APARTMENTS FURNISHED APTS. UNFURNISHED (Cent.) APARTMENTS UNFURNISHED APARTMENTS UNFURNISHED HOUSES FURNISHED (Cont.) STAR PRIVATE ENTRANCE—Large, clean 1763 COLUMBIA THE EVENING B-17 1 RD. N.W, Apt 38; BACHELOR APT., Mass, ELMAR lovely garden rm.: linens, dishes, refer-; #SO mo, 2 young ladies lge. and Wts. GARDENS—A 2-bedrm, Washington, D. C. single. st. p.w. to share well- aves. Lge. dble. rm, kitchenette, apt. development now offering sev- BETHESDA—Attrac. air- USf Belmont —22 furn. apt. with other ladles: conv. pvt. bath and entrance; 1 gentle- eral two-bedroom apts. cooled brick bungalow; level lot, r;s p ST. N.W—Lovely 2nd-fl. location. AD. LOVELY LAWNS at SB9- GEORGETOWN TUESDAY. MAY ID. 1953 20 man: S7O. rental fenced rear yd, gar, kit, --- front single rm., southern exposure; 1 2-1254. 2924 38th at. n.w. includes all utilities. To UNIVERSITY mod. 1 , WIS. AND EM. 3-1499. —l9 reach: Out Bladensburg rd. n e AIR Bendlx: avail June Ist; long oc $s wk —24 i NEWARK ST—Girl to ' Cross, to CONDITIONED lease; <C#nt.) SIUDIO RM.. pvt. entr. 1785 Lanier, . share 2-bedrm apt. with 2 other! 1118 llth ST. N.W.—Completely Trees and Flowers Peace bear tight on Defense Efficiencies and 1-bedroom apt*, short $16.3 mo. TU 2-2575. HOUSES UNFURNISHED girls apt. bldg. hwy. to available for occupancy CITY —24 pi. n.w’. AD. 4-6.170. —22 j in Call EM. 3-1780.; furnished 2-rm. -

A Transportation Guide to 5200 2Nd Street, NW

Washington Latin Public Charter School A Transportation Guide To 5200 2nd Street, NW Table of Contents The Location ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Overview of Transportation Options ………………………………….………………………………………………… 1 Bus Transportation ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Metro Transportation ………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Washington Latin Chartered Bus Service ……………………………………………………………. 3 Carpooling …………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Street Smarts ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 Transportation Details by Wards …………………………………………………………………………………………….5 Ward 1 ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 Ward 2 ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Ward 3 ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 8 Ward 4 ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 9 Ward 5 ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..10 Ward 6 ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..11 Ward 7 ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 12 Ward 8 ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 13 i The Location As of the start of the 2013-14 school year, Washington Latin Public Charter School is located at 5200 2nd Street, NW between Hamilton and Ingraham Streets, on the old site of Rudolph Elementary School. The site, including the gymnasium when completed, will be approximately 75,000 square feet on just over 5 acres and includes a large playing field. We are located in a quiet, residential neighborhood with older buildings populated mostly by older residents and some young families. There are seven schools within -

Before the Committee of the Whole of the Council of the District of Columbia

BEFORE THE COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE OF THE COUNCIL OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA Application of 1255 22nd Street Limited Partnership Closing of Portion of Public Alley Owner of Property System in in Square 70 Square 70, S.O. 15-23283 Bill 21-179 STATEMENT OF THE APPLICANT I. Introduction 1255 22nd Street Limited Partnership (the "Applicant") hereby requests the closing of a portion of a public a lley which bisects their property (Lots 193 and 194) in Square 70 pursuant to D.C. Code, Section 9-202.01 , et seq. Bill 2 1-1 79, a copy of which is attached as Exhibit A, was introduced by Council member Jack Evans to effectuate the proposed alley closing, which is necessary to a llow the development of the Applicant's property with a residenti al building consisting of approximately 197 dwelling units. The Applicant is the fee owner of all of the property abutting the a ll ey to be closed. 1 A copy of the draft alley closing plat showing the area to be closed and the property abutting the same is attached hereto as Exhibit B. As discussed herein, this application meets the statutory requirement for approval pursuant to D.C. Code Section 9-202.01 because the alley to be closed is not necessary for public alley purposes. The alley closing is necessary to construct a 197-unit residential development on the property, which will include the conversion of an obsolete office building on Lot 193 to residential use, and a residenti al addition to be built over 1 The proposed all ey closing and redevelopment of the site will not result in the di splacement of any existing tenants. -

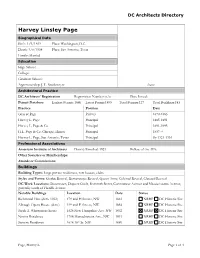

DC Architects Biographies P

DC Architects Directory Harvey Linsley Page Biographical Data Birth: 1/9/1859 Place: Washington, D.C. Death: 1/5/1934 Place: San Antonio, Texas Family: Married Education High School: College: Graduate School: Apprenticeship: J. L. Smithmeyer Source: Architectural Practice DC Architects’ Registration Registration Number: n/a Date Issued: Permit Database Earliest Permit: 1880 Latest Permit:1895 Total Permits:127 Total Buildings:183 Practice Position Date Gray & Page Partner 1879-1885 Harvey L. Page Principal 1885-1891 Harvey L. Page & Co. Principal 1891-1895 H.L. Page & Co. Chicago, Illinois Principal 1897 -? Harvey L. Page, San Antonio, Texas Principal By 1921-1934 Professional Associations American Institute of Architects Date(s) Enrolled: 1921 Fellow of the AIA: Other Societies or Memberships: Awards or Commissions: Buildings Building Types: Large private residences, row houses, clubs. Styles and Forms: Gothic Revival, Romanesque Revival, Queen Anne, Colonial Revival, Classical Revival DC Work Locations: Downtown, Dupont Circle, Sixteenth Street, Connecticut Avenue and Massachusetts Avenue, generally south of Florida Avenue. Notable Buildings Location Date Status Richmond Flats (dem. 1922) 17th and H Streets, NW 1883 NRHP DC Historic Site Albaugh Opera House (dem.) 15th and E Streets, NW 1884 NRHP DC Historic Site Sarah A. Whittemore house 1526 New Hampshire Ave. NW 1892 NRHP DC Historic Site Nevins Residence 1708 Massachusetts Ave., NW 1891 NRHP DC Historic Site Stevens Residence 1628 16th St. NW 1890 NRHP DC Historic Site Page, Harvey L. Page 1 of 4 DC Architects Directory Significance and Contributions Harvey L. Page was born in Washington, D.C., in 1859. He trained in the office of J. -

District of Columbia Builders & Developers Directory

District of Columbia Builders & Developers Directory Prepared for the D.C. Historic Preservation Office (Office of Planning) by EHT Traceries, Inc. September 2012 District of Columbia Builders & Developers Directory Prepared for the District of Columbia Historic Preservation Office (Office of Planning) By EHT Traceries, Inc. September 2012 This program has received Federal financial assistance for the identification, protection, and/or rehabilitation of historic properties and cultural resources in the District of Columbia. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, or disability in its Federally assisted programs. If you believe that you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office of Equal Opportunity, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1849 C Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20240. METHODOLOGY EHT Traceries, Inc. prepared the District of Columbia Builders and Developers Directory for the D.C. Historic Preservation Office, Office of Planning. Work spanned the timeframe from June to September, 2012. EHT Traceries checked a number of standard reference works and resources for all the biographical entries. These were: • Who’s Who in the Nation’s Capital. Selected volumes of Who’s Who in the Nation’s Capital, published between 1921 and 1939, were searched for builders and developers active in those time periods. • History of the City of Washington: It’s Men and Institutions. This volume, published by the Washington Post in 1903, was searched for builders and developers active in the late 19th century. -

![Opcposter1.5SPWEB[1]-1.Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9890/opcposter1-5spweb-1-1-pdf-6059890.webp)

Opcposter1.5SPWEB[1]-1.Pdf

Adams Morgan | Columbia Heights | Howard University | Kalorama | LeDroit Park | Mount Pleasant | Park View | Pleasant Plains | Shaw | Burleith | Chinatown | Downtown | Dupont Circle | Federal Triangle | Foggy Bottom | Georgetown | Logan Circle | Mount Vernon Square | Penn Quarter |Sheridan | Kalorama | Southwest Federal Center | U Street Corridor | West End | American University Park | Berkley | Cathedral Heights | Chevy Chase | Cleveland Park | Colony Hill | Forest Hills | Foxhall | Friendship Heights | Glover Park | Kent | Massachusetts Heights | McLean Gardens | Fort Dupont North Cleveland Park | Observatory Circle | The Palisades | Potomac Heights | Spring Valley | Tenleytown | Wakeeld | Wesley Heights | Woodland | Woodley Park | Barnaby Woods | Brightwood | Brightwood Park | Chevy Chase DC | Colonial Village | Crestwood | Fort Totten | Hawthorne | Manor Park | Petworth | Lamond Riggs | Shepherd Park | Sixteenth Street Heights | Fort Davis Davis | Fort Heights Street | Sixteenth | Lamond Park Riggs | Shepherd | Petworth | Manor Park | Hawthorne Totten | Fort | Crestwood Village Chase DC | Colonial | Chevy Park | Brightwood | Brightwood Woods | Barnaby Park | Woodley | Woodland Heights | Wesley | Wakeeld | Tenleytown | Spring Valley Heights | Potomac Palisades | The Circle | Observatory Park Cleveland North PARA OBTENER AYUDA: Programas que ayudan a los consumidores a pagar sus facturas de servicios públicos. Si tiene preguntas, OPC puede ayudar! 202.727.3071 Programa de Asistencia de Energía para Hogares Programa de Asistencia al -

![Evening Star. (Washington, DC). 1936-10-28 [P B-18]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8367/evening-star-washington-dc-1936-10-28-p-b-18-6358367.webp)

Evening Star. (Washington, DC). 1936-10-28 [P B-18]

NVCSTM1NT PROPERTY WANTED. HOUSES FURNISHED. AND THE MAYAN CAVE $5,000 TO INVE8T IN BUSINESS 'Centime*.) TARZAN '] ! roperty; central location, not over $50 — j2m2S£2^m TAKOMA PARK 8EMI-BUNGALOW. 5 GODD^S^^ T" r7> JJ«S. oo: from owner only. Address Box 48-R. rooms, bath; also sleeping room 2nd floor; tar office. -*< garage in basement, a.m i.; near but line, stores, schools; also rent unfurnished. Phone Bhenherd 2518 evenings. LOTS FOR SALE. WOODRIDGE — SIX-ROOM. DETACHED JUSTNESS LOT. BLADENSBURG PIKE. new. hougt. completely furn., practically 10x150. a.m.l.. $0,500: will build store and • m i., oil heat: $80. Call Potomac 5P45-J. lat. Also :i:i lota. Kenilworth nib Md.; BETHE8DA, MD-BIX .ROOM HOUSE. or all. $850. Call Met. 4757; night*. Urge yard with lruit tree,; oil burner. Greenwood 2232. 20- Frltldalre- newly painted and decorated. 3EAUTIFUL HOME DORSEY. SITES. $750. ALONG $00 month. Call MRS. O. I. dt. Vernon Blvd.. overlooking PotomaO 0:30 p.m- Wisconsin 2813 after _ ilver. Easy terms. Can arrange finance CHEVY CHASE D C..—NEAR 31st AND or building home. Address Box 20-M. Nebraska ave.--Three bed rooms. bath*, 5tat office. .2 oil finished attic: elec, refrigeration, r5-Fr.BuL.DINO LOT. NEAR AND com- 22nd burner: 2-car built-in garage; house Junker H1U rd. n.e.; $1,200. Wise. 4810. pletely furnished. NVE8TIGATE THIS BARGAIN. BEV- + PHILLIPS * CANBY. INC. 'ral lots. 75x135. in beautiful residential 1012 15th St. N.W. Nstlonsl 4000._ lection in Montgomery County, on con- Chevy chase, md — s-room house: crete street with no assessment, only $1.- 4 bed rooms. -

Ward 3 Heritage Guide

WARD 3 HERITAGE GUIDE A Discussion of Ward 3 Cultural and Heritage Resources District of Columbia Office of Planning Ward 3 Heritage Guide Produced by the DC Historic Preservation Office Published 2020 Unless stated otherwise, photographs and images are from the DC Office of Planning collection. This project has been funded in part by U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service Historic Preservation Fund grant funds, administered by the District of Columbia’s Historic Preservation Office. The contents and opinions contained in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of the Interior, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the U.S. Department of the Interior. This program has received Federal financial assistance for the identification, protection, and/or rehabilitation of historic properties and cultural resources in the District of Columbia. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, or disability in its Federally assisted programs. If you believe that you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office of Equal Opportunity, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1849 C Street, NW, Washington, D.C. 20240. Next page: View looking Southeast along Conduit Road (today’s MacArthur Boulevard), ca. 1890, Washington Aqueduct TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................. 1 Ward 3 Overview........................................................................