Characteristics of Clay-Abundant Shale Formations: Use of CO2 For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clay Minerals Soils to Engineering Technology to Cat Litter

Clay Minerals Soils to Engineering Technology to Cat Litter USC Mineralogy Geol 215a (Anderson) Clay Minerals Clay minerals likely are the most utilized minerals … not just as the soils that grow plants for foods and garment, but a great range of applications, including oil absorbants, iron casting, animal feeds, pottery, china, pharmaceuticals, drilling fluids, waste water treatment, food preparation, paint, and … yes, cat litter! Bentonite workings, WY Clay Minerals There are three main groups of clay minerals: Kaolinite - also includes dickite and nacrite; formed by the decomposition of orthoclase feldspar (e.g. in granite); kaolin is the principal constituent in china clay. Illite - also includes glauconite (a green clay sand) and are the commonest clay minerals; formed by the decomposition of some micas and feldspars; predominant in marine clays and shales. Smectites or montmorillonites - also includes bentonite and vermiculite; formed by the alteration of mafic igneous rocks rich in Ca and Mg; weak linkage by cations (e.g. Na+, Ca++) results in high swelling/shrinking potential Clay Minerals are Phyllosilicates All have layers of Si tetrahedra SEM view of clay and layers of Al, Fe, Mg octahedra, similar to gibbsite or brucite Clay Minerals The kaolinite clays are 1:1 phyllosilicates The montmorillonite and illite clays are 2:1 phyllosilicates 1:1 and 2:1 Clay Minerals Marine Clays Clays mostly form on land but are often transported to the oceans, covering vast regions. Kaolinite Al2Si2O5(OH)2 Kaolinite clays have long been used in the ceramic industry, especially in fine porcelains, because they can be easily molded, have a fine texture, and are white when fired. -

Effective Porosity of Geologic Materials First Annual Report

ISWS CR 351 Loan c.l State Water Survey Division Illinois Department of Ground Water Section Energy and Natural Resources SWS Contract Report 351 EFFECTIVE POROSITY OF GEOLOGIC MATERIALS FIRST ANNUAL REPORT by James P. Gibb, Michael J. Barcelona. Joseph D. Ritchey, and Mary H. LeFaivre Champaign, Illinois September 1984 Effective Porosity of Geologic Materials EPA Project No. CR 811030-01-0 First Annual Report by Illinois State Water Survey September, 1984 I. INTRODUCTION Effective porosity is that portion of the total void space of a porous material that is capable of transmitting a fluid. Total porosity is the ratio of the total void volume to the total bulk volume. Porosity ratios traditionally are multiplied by 100 and expressed as a percent. Effective porosity occurs because a fluid in a saturated porous media will not flow through all voids, but only through the voids which are inter• connected. Unconnected pores are often called dead-end pores. Particle size, shape, and packing arrangement are among the factors that determine the occurance of dead-end pores. In addition, some fluid contained in inter• connected pores is held in place by molecular and surface-tension forces. This "immobile" fluid volume also does not participate in fluid flow. Increased attention is being given to the effectiveness of fine grain materials as a retardant to flow. The calculation of travel time (t) of con• taminants through fine grain materials, considering advection only, requires knowledge of effective porosity (ne): (1) where x is the distance travelled, K is the hydraulic conductivity, and I is the hydraulic gradient. -

Halloysite Formation Through in Situ Weathering of Volcanic Glass From

Ciay Minerals (1988) 23, 423-431 mineralogy. Phys. ition of Mössbauer L HALLOYSITE FORMATION THROUGH Ih' SITU shaviour? J. Mag. WEATHERING OF VOLCANIC GLASS FROM 3n analysis of two TRACHYTIC PUMICES, VICO'S VOLCANO, ITALY d.X, 29-31. ir Conímbriga and P. QUANTIN, J. GAUTHEYROU AND P. LORENZONI* ts correlation with .central Portugal). ORSTOM, 70 route d'Aulnay. 93143 Bondy Cedex, France, and *ISSDS, Piazza d'Azeglio 30, Firenze, Italy ibrico da cerâmica (Received October 1987; revised 5 April 1988) of dolomites, clays ABSTRACT: The weathering of a trachytic pumice within a pyroclastic flow underlying an ., MADWCKA.G., andic-brown soil on the volcano Vico has been studied. The main mineral formed is a spherical 10 A halloysite which has been shown by SEM and in situ microprobe analysis to have formed norphology on the directly from the glass. The major mineralogical characteristics as determined by XRD, IR, DTA, TEM and microdiffraction are typical of 10 A halloysite. However, some minor mineralogical properties and the high Fe and K contents, suggest that it is an interstratification of 74% halloysite and 26% illite-smectite. The calculated formula of the hypothetical 2:l minerals reveals an Fe- and K-rich clay, with high tetrahedral substitution, like an Fe-rich vermiculite, but the detailed structure of this mineral remains uncertain. This study deals with the weathering of trachytic pumices to a white clay which seems to be derived directly from glass, without change in texture. This clay is a well crystallized 10 A halloysite, and although nearly white in colour, has an unusual composition being rich in Fe and Ti, and having a high K content. -

Mixed-Layer Illite-Smectite in Pennsylvanian-Aged Paleosols: Assessing Sources of Illitization in the Illinois Basin

minerals Article Mixed-Layer Illite-Smectite in Pennsylvanian-Aged Paleosols: Assessing Sources of Illitization in the Illinois Basin Julia A. McIntosh 1,* , Neil J. Tabor 1 and Nicholas A. Rosenau 2 1 Roy M. Huffington Department of Earth Sciences, Southern Methodist University, P.O. Box 750395, Dallas, TX 75275, USA; [email protected] 2 Ocean and Coastal Management Branch, Office of Wetlands Oceans and Watersheds, United States Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC 20004, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-214-768-2750 Abstract: Mixed-layer illite-smectite (I-S) from a new set of Pennsylvanian-aged Illinois Basin under- clays, identified as paleosols, are investigated to assess the impact of (1) regional diagenesis across the basin and (2) the extent to which ancient environments promoted illitization during episodes of soil formation. Interpretations from Reichweite Ordering and D◦ 2q metrics applied to X-ray diffraction patterns suggest that most I-S in Illinois Basin paleosols are likely the product of burial diagenetic processes and not ancient soil formation processes. Acid leaching from abundant coal units and hydrothermal brines are likely diagenetic mechanisms that may have impacted I-S in Pennsylvanian paleosols. These findings also suggest that shallowly buried basins (<3 km) such as the Illinois Basin may still promote clay mineral alteration through illitization pathways if maximum burial occurred in the deep past and remained within the diagenetic window for extended periods of time. More importantly, since many pedogenic clay minerals may have been geochemically reset during illitization, sources of diagenetic alteration in the Illinois Basin should be better understood if Citation: McIntosh, J.A.; Tabor, N.J.; Pennsylvanian paleosol minerals are to be utilized for paleoclimate reconstructions. -

Medwin Publishers

5/16/2019 Medwin Publishers (https://www.facebook.com/Medwin-Publishers-1020468474656239/?fref=ts) (https://twitter.com/MedWinPublisher) (https://www.linkedin.com/in/medwin-publishers/) (https://medwinpublishers.com/services.php) (https://medwinpublishers.com/faqs.php) (https://medwinpublishers.com/contact-us.php) (https://medwinpublishers.com) Petroleum & Petrochemical Engineering Journal (PPEJ) ISSN : 2578-4846 (https://portal.issn.org/resource/ISSN/2578- 4846#) IF : 1.5696 Journal Home (index.php) Classiication (classiication.php) Editorial Board (editorial-board.php) Article In Press (articles-in-press.php) Submit Manuscript Current Issue (current-issue.php) (https://medwinpublishers.com/submit- manuscript.php) Archive (archive.php) Special Issues (specialissues.php) Editor-in-Chief https://medwinpublishers.com/PPEJ/editorial-board.php 1/43 5/16/2019 Medwin Publishers Editors Jorge H B Sampaio Colorado School of Mines USA View Proile Fathi Elldakli Texas Tech University USA View Proile Abdennour C Seibi University of Louisiana at Lafayette USA View Proile Alireza Heidari California South University USA View Proile Submit ManuscriptLouis Houston (https://medUniversity of Louisiana at Lafwinpublishers.com/submit-ayette manuscript.php) USA View Proile https://medwinpublishers.com/PPEJ/editorial-board.php 2/43 5/16/2019 Medwin Publishers Ganesh Raj Joshi United Nations Centre for Regional Development Japan View Proile Satish J Parulekar Illinois Institute of Technology USA View Proile Mohammad Asadikiya Worcester Polytechnic Institute -

Illite Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg Gmbh Alain Meunier • Bruce Velde

Illite Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg GmbH Alain Meunier • Bruce Velde Illite Origins, Evolution and Metamorphism With 138 Figures Springer Professor Dr. Alain Meunier University of Poitiers UMR 6532 CNRS HYDRASA Laboratory 40, Avenue du Recteur Pineau 86022 Poitiers, France E-mail [email protected] Dr. Bruce Velde Research Director CNRS Geology Laboratory UMR 8538 CNRS Ecole Normale Superieure 24, rue Lhomond 75231 Paris, France E-mail [email protected] ISBN 978-3-642-05806-6 ISBN 978-3-662-07850-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-662-07850-1 Library of Congress Control Number: '3502272 Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in die Deutsche Nationalbibliography; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at <http://dnb.ddb.de>. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of this material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitations, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilm or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9, 1965, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer-Verlag. Violations are liable for prosecution under the German Copyright Law. springeronline.com © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2004 Originally published by Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg New York in 2004. Softcover reprint of the hardcover I st edition 2004 The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

An Alternative to Conventional Rock Fragmentation Methods Using SCDA: a Review

energies Review An Alternative to Conventional Rock Fragmentation Methods Using SCDA: A Review Radhika Vidanage De Silva 1, Ranjith Pathegama Gamage 1,* and Mandadige Samintha Anne Perera 1,2 1 Deep Earth Energy Laboratory, Department of Civil Engineering, Monash University, Building 60, Melbourne 3800, Victoria, Australia; [email protected] (R.V.D.S.); [email protected] (M.S.A.P.) 2 Department of Infrastructure Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, the University of Melbourne, Building 176, Block D, Grattan Street, Parkville 3010, Victoria, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-3-9905-4982 Academic Editor: Moran Wang Received: 9 October 2016; Accepted: 10 November 2016; Published: 17 November 2016 Abstract: Global energy and material consumption are expected to rise in exponential proportions during the next few decades, generating huge demands for deep earth energy (oil/gas) recovery and mineral processing. Under such circumstances, the continuation of existing methods in rock fragmentation in such applications is questionable due to the proven adverse environmental impacts associated with them. In this regard; the possibility of using more environmentally friendly options as Soundless Chemical Demolition Agents (SCDAs) play a vital role in replacing harmful conventional rock fragmentation techniques for gas; oil and mineral recovery. This study reviews up to date research on soundless cracking demolition agent (SCDA) application on rock fracturing including its limitations and strengths, possible applications in the petroleum industry and the possibility of using existing rock fragmentation models for SCDA-based rock fragmentation; also known as fracking. Though the expansive properties of SCDAs are currently used in some demolition works, the poor usage guidelines available reflect the insufficient research carried out on its material’s behavior. -

Mechanical Characterization of Low Permeable Siltstone Under Different Reservoir Saturation Conditions: an Experimental Study

energies Article Mechanical Characterization of Low Permeable Siltstone under Different Reservoir Saturation Conditions: An Experimental Study Ayal Wanniarachchi 1 , Ranjith Pathegama Gamage 1 , Qiao Lyu 2,*, Samintha Perera 1,3 , Hiruni Wickramarathne 1 and Tharaka Rathnaweera 1 1 Deep Earth Energy Laboratory, Department of Civil Engineering, Monash University, Building 60, Melbourne 3800, Australia; [email protected] (A.W.); [email protected] (R.P.G.); [email protected] (S.P.); [email protected] (H.W.); [email protected] (T.R.) 2 School of Geosciences and Info-physics, Central South University, Changsha 410012, China 3 Department of Infrastructure Engineering, The University of Melbourne, Building 175, Melbourne 3010, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 27 November 2018; Accepted: 18 December 2018; Published: 21 December 2018 Abstract: Hydro-fracturing is a common production enhancement technique used in unconventional reservoirs. However, an effective fracturing process requires a precise understanding of a formation’s in-situ strength behavior, which is mainly dependent on the formation’s in-situ stresses and fluid saturation. The aim of this study is to identify the effect of brine saturation (concentration and degree of saturation (DOS)) on the mechanical properties of one of the common unconventional reservoir rock types, siltstone. Most common type of non-destructive test: acoustic emission (AE) was used in conjunction with the destructive tests to investigate the rock properties. Unconfined compressive strength (UCS) and splitting tensile strength (STS) experiments were carried out for 78 varyingly saturated specimens utilizing ARAMIS (non-contact and material independent measuring system) and acoustic emission systems to determine the fracture propagation. -

Clay Minerals

CLAY MINERALS CD. Barton United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Aiken, South Carolina, U.S.A. A.D. Karathanasis University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, U.S.A. INTRODUCTION of soil minerals is understandable. Notwithstanding, the prevalence of silicon and oxygen in the phyllosilicate structure is logical. The SiC>4 tetrahedron is the foundation Clay minerals refers to a group of hydrous aluminosili- 2 of all silicate structures. It consists of four O ~~ ions at the cates that predominate the clay-sized (<2 |xm) fraction of apices of a regular tetrahedron coordinated to one Si4+ at soils. These minerals are similar in chemical and structural the center (Fig. 1). An interlocking array of these composition to the primary minerals that originate from tetrahedral connected at three corners in the same plane the Earth's crust; however, transformations in the by shared oxygen anions forms a hexagonal network geometric arrangement of atoms and ions within their called the tetrahedral sheet (2). When external ions bond to structures occur due to weathering. Primary minerals form the tetrahedral sheet they are coordinated to one hydroxyl at elevated temperatures and pressures, and are usually and two oxygen anion groups. An aluminum, magnesium, derived from igneous or metamorphic rocks. Inside the or iron ion typically serves as the coordinating cation and Earth these minerals are relatively stable, but transform- is surrounded by six oxygen atoms or hydroxyl groups ations may occur once exposed to the ambient conditions resulting in an eight-sided building block termed an of the Earth's surface. Although some of the most resistant octohedron (Fig. -

Download PDF About Minerals Sorted by Mineral Group

MINERALS SORTED BY MINERAL GROUP Most minerals are chemically classified as native elements, sulfides, sulfates, oxides, silicates, carbonates, phosphates, halides, nitrates, tungstates, molybdates, arsenates, or vanadates. More information on and photographs of these minerals in Kentucky is available in the book “Rocks and Minerals of Kentucky” (Anderson, 1994). NATIVE ELEMENTS (DIAMOND, SULFUR, GOLD) Native elements are minerals composed of only one element, such as copper, sulfur, gold, silver, and diamond. They are not common in Kentucky, but are mentioned because of their appeal to collectors. DIAMOND Crystal system: isometric. Cleavage: perfect octahedral. Color: colorless, pale shades of yellow, orange, or blue. Hardness: 10. Specific gravity: 3.5. Uses: jewelry, saws, polishing equipment. Diamond, the hardest of any naturally formed mineral, is also highly refractive, causing light to be split into a spectrum of colors commonly called play of colors. Because of its high specific gravity, it is easily concentrated in alluvial gravels, where it can be mined. This is one of the main mining methods used in South Africa, where most of the world's diamonds originate. The source rock of diamonds is the igneous rock kimberlite, also referred to as diamond pipe. A nongem variety of diamond is called bort. Kentucky has kimberlites in Elliott County in eastern Kentucky and Crittenden and Livingston Counties in western Kentucky, but no diamonds have ever been discovered in or authenticated from these rocks. A diamond was found in Adair County, but it was determined to have been brought in from somewhere else. SULFUR Crystal system: orthorhombic. Fracture: uneven. Color: yellow. Hardness 1 to 2. -

Structural Variations in Illite and Chlorite in the Belt Supergroup Western Montana and Northern Idaho

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1991 Structural variations in illite and chlorite in the Belt Supergroup western Montana and northern Idaho Peter Ryan The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ryan, Peter, "Structural variations in illite and chlorite in the Belt Supergroup western Montana and northern Idaho" (1991). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 7192. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/7192 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY Copying allowed as provided under provisions of the Fair Use Section of the U.S. COPYRIGHT LAW, 1976. Any copying for commercial purposes or financM gain may be undertaken only with the author’s written consent. MontanaUniversity of Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. STRUCTURAL VARIATIONS IN IlilTE AND CHLORITE IN THE BELT SUPERGROUP, WESTERN MONTANA AND NORTHERN IDAHO by PETER RYAN A.B., Dartmouth College, 1988 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1991 iners ïan. Graduate School Z,g,. -

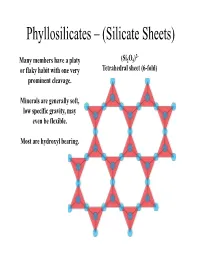

Phyllosilicates – (Silicate Sheets)

Phyllosilicates – (Silicate Sheets) 2- Many members have a platy (Si2O5) or flaky habit with one very Tetrahedral sheet (6-fold) prominent cleavage . Minerals are generally soft, low specific gravity, may even be flexible. Most are hydroxyl bearing. Each tetrahedra is bound to three neiggghboring tetrahedra via three basal bridging oxygens. The apical oxygen of each tetrahedral in a sheet all point in the same direction. The sheets are stacked either apice-to- apice or base-to-base. In an undistorted sheet the hydroxyl (OH) group sits in the centre and each outlined triangle is equivalent. Sheets within sheets…. Apical oxygens, plus the –OH group, coordinate a 6-fold (octahedral) site (XO6). These octahedral sites form infinitely extending sheets. All the octahedra lie on triangular faces, oblique to the tetrahedral sheets. The most common elements found in the 6 -fold site are Mg (or Fe) or Al . Dioctahedral vs Trioctahedral Mg and Al have different charges, but the sheet must remain charge neutral . With 6 coordinating oxygens, we have a partial charge of -6. How many Mg2+ ions are required to retain neutrality? How many Al3+ ions are required to retain neutrality? Mg occupies all octahedral sites, while Al will only occupy 2 out of every 3. The stacking of the sheets dictates the crystallography and c hem istry o f eac h o f t he p hhyll llosili cates. Trioctahedral Dioctahedral O Brucite Gibbsite Hydroxyl Magnesium Aluminium Trioctahedral Is this structure charge neutral? T O T Interlayer Cation T O T Potassium (K+) Phlogopite (Mg end-member biotite) Dioctahedral Is this structure charge neutral? T O T Interlayer Cation T O T Potassium (K+) Muscovite Compositional variation in phyllosilicates There is little solid solution between members of the dioctahedral and trioctahedral groups.