Korea-UN Command (Working File) (2)” of the NSC East Asian and Pacific Affairs Staff: Files, 1969-1977 at the Gerald R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ECUR'ity GENERAL ., S/3079 Ouncll 7 August 1953 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH

I'{ f , r: u '" A,, UN:) Distr. ECUR'ITY GENERAL ., S/3079 OUNCll 7 August 1953 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH . ;, , LETTER DATED 7 AUGUST 1953 FROM THE ACTING UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE TO THE 'UNITED NATIONS, ADDRESSED TO THE SECRETARY -GENERAL, TRANSMITTING A SPECIAL REPORT OF 'l"'HE UNIFIED COMMAND ON THE ARMISTICE IN KOREA Il'iJ ACCORDANCE WITH THE SECURITY COUNCIL RESOLUTION OF 7 JULY 1950 (S/1588) " ... I have the honor to refer to paragraph 6 of the resolution of the Security Council of 7 July 1950, requesting the United States to proVide the Security • . l .' •• ~ Council with reJ?orts, as appropriate, on the course of action taken under the United Nations Command. In compliance with this resolution, there is enclo~ed herewith, for circulation to the members of the Security Council, a special report of the " , Unified Command on the annistice in Korea. With ,this report the Unified Command is submitting the official text of the Armistice Agreement entered into in Korea , " on 27 July 1953. I would be "grateful if you also would circulate copies of this special report . .' . and the Armistice Agreement to the Members of the General Assembly for their 1'" ' informat.ion .=.1 (Signed) James J. WADSvlORTH Acting United States Representative to the United Nations y C1rcu1D.ted to the Members of the General Assembly by document A/2431. 53-21837 S/3079 English Page 2 SPECIAl, roiPORT OF THE UND!'!ED COMMAND ON TEE ARMISTICE IN KOREA I. FOREWORD The Government of the United States, as the Unified Command, transmits herewith a s-peclal report on the United. -

History and Structure of the United Nations

History and Structure of the United Nations Nadezhda Tomova University of Bologna Supervisor: dr. Francesca Sofia Word Count: 21, 967 (excluding bibliography) March, 2014 Content Chapter I: The United Nations: History of Ideas St. Augustine Thomas Aquino Dante Alighieri George Podebrad of Bohemia Desiderius Erasmus The Duc de Sully Emeric Cruce Hugo Grotius John Locke William Penn Abbe de Saint-Pierre Jean-Jacques Rousseau Immanuel Kant Emeric Vattel Napoleon Bonaparte and the First French Empire The Congress of Vienna and the balance of power system Bismarck’s system of fluctuating alliances The League of Nations Chapter II: Structure of the United Nations The creation of the United Nations The constitutional dimension of the Charter of the United Nations Affiliate agencies General purposes and principles of the United Nations The General Assembly The Economic and Social Council The Trusteeship Council The International Court of Justice The Security Council Chapter III: Peace and Security – from the War in Korea to the Gulf War The War in Korea UNEF I and the Suez Canal Crisis The Hungarian Revolution ONUC and the Congo Crisis The 1960’s and the 1970’s The 1980’s The Gulf War Chapter IV: The United Nations in the post-Cold War Era Agenda for Peace UNPROFOR in Bosnia Agenda for Development Kofi Annan’s Reform Agenda 1997-2006 The Millennium Summit The Brahimi Reforms Conclusion Bibliography The United Nations: History of Ideas The United Nations and its affiliate agencies embody two different approaches to the quest for peace that historically appear to conflict with each other. The just war theory and the pacifist tradition evolved along quite separate paths and had always been considered completely opposite ideas. -

Korean War Timeline America's Forgotten War by Kallie Szczepanski, About.Com Guide

Korean War Timeline America's Forgotten War By Kallie Szczepanski, About.com Guide At the close of World War II, the victorious Allied Powers did not know what to do with the Korean Peninsula. Korea had been a Japanese colony since the late nineteenth century, so westerners thought the country incapable of self-rule. The Korean people, however, were eager to re-establish an independent nation of Korea. Background to the Korean War: July 1945 - June 1950 Library of Congress Potsdam Conference, Russians invade Manchuria and Korea, US accepts Japanese surrender, North Korean People's Army activated, U.S. withdraws from Korea, Republic of Korea founded, North Korea claims entire peninsula, Secretary of State Acheson puts Korea outside U.S. security cordon, North Korea fires on South, North Korea declares war July 24, 1945- President Truman asks for Russian aid against Japan, Potsdam Aug. 8, 1945- 120,000 Russian troops invade Manchuria and Korea Sept. 9, 1945- U.S. accept surrender of Japanese south of 38th Parallel Feb. 8, 1948- North Korean People's Army (NKA) activated April 8, 1948- U.S. troops withdraw from Korea Aug. 15, 1948- Republic of Korea founded. Syngman Rhee elected president. Sept. 9, 1948- Democratic People's Republic (N. Korea) claims entire peninsula Jan. 12, 1950- Sec. of State Acheson says Korea is outside US security cordon June 25, 1950- 4 am, North Korea opens fire on South Korea over 38th Parallel June 25, 1950- 11 am, North Korea declares war on South Korea North Korea's Ground Assault Begins: June - July 1950 Department of Defense / National Archives UN Security Council calls for ceasefire, South Korean President flees Seoul, UN Security Council pledges military help for South Korea, U.S. -

Report of the United Nations Commission for The

I 1 UNITED NATIONS tI i } REPORT OF THE " . i \ t UNITED NATIONS COMMISSION FOR THE UNIFICATION AND REHABILITATION OF I{OREA i rJ ii· ( GENERAL ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL RECORDS : ELEV~NTH S~SSION SUPPL~MENT No. 13 (A/3I72) r ~ New York, 1956 NOTE Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraphs Page Introduction ......•.•........•••..•.• •. ..• .•. v Chapter I. Organization and activities of the Commission and its Committee A. Consideration of the Commission's report by the General Assembly at its tenth session .•.•.•••...•.•..•.•.. 1 - 2 1 B. Organization and present position •••••••.•.•.••.•.. 3 - 4 1 Chapte! 11. The Korean question and the armistice 5 - 15 1 Chapter Ill. Representative government in the Republic" of Korea A. Introduction ••..•••••.•.•.•••.•.•••.•.••. 16 - 17 3 B. The Executive ...•.••••.•...••.•.•..•••••.••. 18 3 (!!) Presidential and vice-presfdential elections •.••.••. 19 - 24 3 (Q) Observation of the elections by the Committee .•.•.. 25 - 30 4 C. The Legislature ..•.•••.••..••••.•..•.••• 31 - 36 4 D. Party structure ............•••.•••.•.•.••.•.. 37 - 39 5 E. Local government ..•...•••...•••• •......•••.. 40 - 42 5 Chapter IV. Economic situation and progress of reconstruction in the Republic of Korea A. General review of the economic and financial situation .•.. 43 - 49 5 B. International aid to the Republic of Korea ..•.••••••.. 50 - 51 7 1. United States aid ..••••.....•••••.••••..•••. 52 - 55 7 2. The UNKRA programme .•.••.•.•••.•.....•••. 56 - 60 7 (ill Investment projects ••.•.•...••••.•..••.•. 61 - 62 8 (Q) Other programmes ....•.....•..••••.••.•• 63 - 65 8 (ill Joint programmes ..•..••.•..••...•••••..• 66 - 67 9 (9) Voluntary agencies •...•••••.••..••••••... 68 9 (~ Technical assistance .....•...••••••••••.•• 69 9 (f) Future plans of UNKRA .••.•...•.•.•.•••••. -

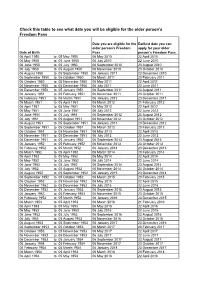

Copy of Age Eligibility from 6 April 10

Check this table to see what date you will be eligible for the older person's Freedom Pass Date you are eligible for the Earliest date you can older person's Freedom apply for your older Date of Birth Pass person's Freedom Pass 06 April 1950 to 05 May 1950 06 May 2010 22 April 2010 06 May 1950 to 05 June 1950 06 July 2010 22 June 2010 06 June 1950 to 05 July 1950 06 September 2010 23 August 2010 06 July 1950 to 05 August 1950 06 November 2010 23 October 2010 06 August 1950 to 05 September 1950 06 January 2011 23 December 2010 06 September 1950 to 05 October 1950 06 March 2011 20 February 2011 06 October 1950 to 05 November 1950 06 May 2011 22 April 2011 06 November 1950 to 05 December 1950 06 July 2011 22 June 2011 06 December 1950 to 05 January 1951 06 September 2011 23 August 2011 06 January 1951 to 05 February 1951 06 November 2011 23 October 2011 06 February 1951 to 05 March 1951 06 January 2012 23 December 2011 06 March 1951 to 05 April 1951 06 March 2012 21 February 2012 06 April 1951 to 05 May 1951 06 May 2012 22 April 2012 06 May 1951 to 05 June 1951 06 July 2012 22 June 2012 06 June 1951 to 05 July 1951 06 September 2012 23 August 2012 06 July 1951 to 05 August 1951 06 November 2012 23 October 2012 06 August 1951 to 05 September 1951 06 January 2013 23 December 2012 06 September 1951 to 05 October 1951 06 March 2013 20 February 2013 06 October 1951 to 05 November 1951 06 May 2013 22 April 2013 06 November 1951 to 05 December 1951 06 July 2013 22 June 2013 06 December 1951 to 05 January 1952 06 September 2013 23 August 2013 06 -

1 the United Nations Command and the Sending States Colonel Shawn

The United Nations Command and the Sending States Colonel Shawn P. Creamer, U.S. Army Abstract The United Nations Command is the oldest and most distinguished of the four theater-level commands in the Republic of Korea. Authorized by the nascent United Nations Security Council, established by the United States Government, and initially commanded by General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, the United Nations Command had over 930,000 servicemen and women at the time the Armistice Agreement was signed. Sixteen UN member states sent combat forces and five provided humanitarian assistance to support the Republic of Korea in repelling North Korea’s attack. Over time, other commands and organizations assumed responsibilities from the United Nations Command, to include the defense of the Republic of Korea. The North Korean government has frequently demanded the command’s dissolution, and many within the United Nations question whether the command is a relic of the Cold War. This paper examines the United Nations Command, reviewing the establishment of the command and its subordinate organizations. The next section describes the changes that occurred as a result of the establishment of the Combined Forces Command in 1978, as well as the implications of removing South Korean troops from the United Nations Command’s operational control in 1994. The paper concludes with an overview of recent efforts to revitalize the United Nations Command, with a focus on the command’s relationship with the Sending States. Keywords: United States, Republic of Korea, United Nations, Security Council, Sending States, United Nations Command, Military Armistice Commission, United Nations Command-Rear, U.S. -

Military Component of United Nations Peace-Keeping Operations

JIU/REP/95/11 MILITARY COMPONENT OF UNITED NATIONS PEACE-KEEPING OPERATIONS Prepared by Andrzej T. Abraszewski Richard V. Hennes Boris P. Krasulin Khalil Issa Othman Joint Inspection Unit - iii - Contents Paragraphs Pages Acronyms v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS vi INTRODUCTION 1 - 3 1 I. MANDATES FOR PEACE-KEEPING: MANAGERIAL ASPECTS 4 - 24 2 A. The decision-making process 6 - 7 2 B. Consultations, exchanges of views and briefings 8 - 16 2 C. Command and control 17 - 24 4 D. Recommendations 6 II. AVAILABILITY OF TROOPS AND EQUIPMENT 25 - 59 8 A. Rapid reaction force 29 - 32 8 B. Stand-by arrangements 33 - 36 9 C. Rapid reaction capability 37 - 38 10 D. Role of/and relationship with regional organizations and arrangements 39 - 42 10 E. Issues related to troops and equipment 43 - 59 10 1. Rotation of troops 44 - 46 10 2. Safety of personnel 47 - 48 12 3. Death and disability benefits 49 - 50 12 4. Reimbursement for Equipment 51 - 54 12 5. Procurement of equipment 55 - 59 13 F. Recommendations 14 III. CAPACITY OF THE UNITED NATIONS SECRETARIAT 60 - 89 16 A. Headquarters 63 - 67 16 B. The field 68 - 71 18 C. Elements of successful peace-keeping operations 72 - 89 19 1. Planning 73 - 77 19 2. Legal arrangements 78 - 80 20 3. Training 81 - 84 20 4. Information 85 - 87 21 5. Logistic support services 88 - 89 21 D. Recommendations 22 Notes 23 - iv - Contents (2) Annexes I. Statement by the President of the Security Council S/PRST/1994/62 of 4 November 1994 II. -

Inventory Dep.288 BBC Scottish

Inventory Dep.288 BBC Scottish National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland Typescript records of programmes, 1935-54, broadcast by the BBC Scottish Region (later Scottish Home Service). 1. February-March, 1935. 2. May-August, 1935. 3. September-December, 1935. 4. January-April, 1936. 5. May-August, 1936. 6. September-December, 1936. 7. January-February, 1937. 8. March-April, 1937. 9. May-June, 1937. 10. July-August, 1937. 11. September-October, 1937. 12. November-December, 1937. 13. January-February, 1938. 14. March-April, 1938. 15. May-June, 1938. 16. July-August, 1938. 17. September-October, 1938. 18. November-December, 1938. 19. January, 1939. 20. February, 1939. 21. March, 1939. 22. April, 1939. 23. May, 1939. 24. June, 1939. 25. July, 1939. 26. August, 1939. 27. January, 1940. 28. February, 1940. 29. March, 1940. 30. April, 1940. 31. May, 1940. 32. June, 1940. 33. July, 1940. 34. August, 1940. 35. September, 1940. 36. October, 1940. 37. November, 1940. 38. December, 1940. 39. January, 1941. 40. February, 1941. 41. March, 1941. 42. April, 1941. 43. May, 1941. 44. June, 1941. 45. July, 1941. 46. August, 1941. 47. September, 1941. 48. October, 1941. 49. November, 1941. 50. December, 1941. 51. January, 1942. 52. February, 1942. 53. March, 1942. 54. April, 1942. 55. May, 1942. 56. June, 1942. 57. July, 1942. 58. August, 1942. 59. September, 1942. 60. October, 1942. 61. November, 1942. 62. December, 1942. 63. January, 1943. -

November 18, 1975 United Nationals General Assembly Resolution 3390A/3390B, "Question of Korea"

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified November 18, 1975 United Nationals General Assembly Resolution 3390A/3390B, "Question of Korea" Citation: “United Nationals General Assembly Resolution 3390A/3390B, "Question of Korea",” November 18, 1975, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, United Nations Office of Public Information, ed., Yearbook of the United Nations 1975 (New York: United Nations, Office of Public Information, 1978), 203-204. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/117737 Summary: Credits: This document was made possible with support from the Leon Levy Foundation. Original Language: English Contents: English Transcription A The General Assembly, Mindful of the hope expressed by it in resolution 3333 (XXIX) of 17 December 1974, Desiring that progress be made towards the attainment of the goal of peaceful reunification of Korea on the basis of the freely expressed will of the Korean people, Recalling its satisfaction with the issuance of the joint communiqué at Seoul and Pyongyang on 4 July 1972 and the declared intention of both the South and the North of Korea to continue the dialogue between them, Furtherrecalling that, by its resolution 711 A (VII) of 28 August 1953, the General Assembly noted with approval the Armistice Agreement of 27 July 1953, and that, in its resolution 811 (IX) of 11 December 1954, it expressly took note of the provision of the Armistice Agreement which requires that the Agreement shall remain in effect until expressly superseded either -

Participation in the Security Council by Country 1946-2010

Repertoire of the Practice of the Security Council http://www.un.org/en/sc/repertoire/ Participation in the Security Council by Country 1946-2010 Country Term # of terms Total Presidencies # of Presidencies years on the Council Algeria 3 6 4 2004-2005 December 2004 1 1988-1989 May 1988,August 1989 2 1968-1969 July 1968 1 Angola 1 2 1 2003-2004 November 2003 1 Argentina 8 16 13 2005-2006 January 2005,March 2006 2 1999-2000 February 2000 1 1994-1995 January 1995 1 1987-1988 March 1987,June 1988 2 1971-1972 March 1971,July 1972 2 1966-1967 January 1967 1 1959-1960 May 1959,April 1960 2 1948-1949 November 1948,November 1949 2 Australia 4 8 8 1985-1986 November 1985 1 1973-1974 October 1973,December 1974 2 1956-1957 June 1956,June 1957 2 1946-1947 February 1946,January 1947,December 3 1947 Austria 3 6 3 2009-2010 ---no presidencies this term (yet)--- 0 1991-1992 March 1991,May 1992 2 1973-1974 November 1973 1 Bahrain 1 2 1 1998-1999 December 1998 1 Bangladesh 2 4 3 2000-2001 March 2000,June 2001 2 1 Repertoire of the Practice of the Security Council http://www.un.org/en/sc/repertoire/ 1979-1980 October 1979 1 Belgium 5 10 11 2007-2008 June 2007,August 2008 2 1991-1992 April 1991,June 1992 2 1971-1972 April 1971,August 1972 2 1955-1956 July 1955,July 1956 2 1947-1948 February 1947,January 1948,December 3 1948 Benin 2 4 3 2004-2005 February 2005 1 1976-1977 March 1976,May 1977 2 Bolivia 2 4 5 1978-1979 June 1978,November 1979 2 1964-1965 January 1964,December 1964,November 3 1965 Bosnia and Herzegovina 1 2 0 2010-2011 ---no presidencies this -

The United Nations' Oldest and Only Collective Security Enforcement Army, the United Nations Command in Korea*

Penn State International Law Review Volume 6 Article 2 Number 1 Dickinson Journal of International Law 1987 Self Doubts on Approaching Forty: The nitU ed Nations' Oldest and Only Collective Security Enforcement Army, the United Nations Command in Korea Samuel Pollack Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Pollack, Samuel (1987) "Self Doubts on Approaching Forty: The nitU ed Nations' Oldest and Only Collective Security Enforcement Army, the United Nations Command in Korea," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 6: No. 1, Article 2. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol6/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Self Doubts on Approaching Forty: The United Nations' Oldest and Only Collective Security Enforcement Army, The United Nations Command in Korea* Samuel Pollack** I. Introduction The General Assembly . calls upon all states and au- thorities to continue to lend every assistance to the United Na- tions action in Korea.' "In effect," a UN official said, "the United Nations for years have dissociated itself from the United Nations Command 2 in Korea, even in the absence of formal action to dissolve it." One of the minor accomplishments of the 1953 Korean Armi- stice Agreement, which ended the hostilities in Korea between the United Nations Command (UNC) and the North Korean/Chinese armed forces, was to carve out, at the Peninsula's midpoint, a four kilometer wide Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) to serve as a buffer zone and to keep the belligerents safely apart. -

Official Gazette

TH E O FFICIA L G A ZE TT E 0F TH E COLON Y AN D PROTEW OJ8LA TE 0F EEN YA Pe lzshed under the A uthorlty of H zs E Kcelleney tbe G o& ernor af the Colony and Protectolate of K enya V oI. LII- N /. 35 x A m o ex A ugust 1, 1950 Pnce 50 Cents sewstereu as a xewspap r at tho o p o , lu bhssed every auesdd, . n. L= = ''- CON TEN TS OH :G AL G AZE'ITE (IFFICIAL G AZETTIL--COFI/: G ovt N otlce N o - à'&Gb, General N otzce lVo 83g- A ppolntm ents, etc 593 Com pam d-s Ortlznance 1739, 1755, 1761 8e ---l-he Kenya M eat Com m lsslon- Apgofntm ent 593 M edlcal Practlltumers Reglstered 1762 841-842- n e M lnlng Ordm ance lgc - N etlces 594 Plots at Varo M oru 1763 843--O b1tuary 594 N alrobl Pnvatt Steets Costs 1768 844- The Dlseases of Anlm als Chrdlnance 594 Credlt t 7 Natlyzs (Control) Ordznal ce- Exemptlons 1 769 845- -141e Cosee Industry (F lnanclal ANsIst m ce) Ordlnan cem 1944 594 846- 711e N atlve Authorlty Ordlnance- A ppolntm ents 595 847- The M arnage O rdlnance- N otlce 595 SUPPLEM ENT No 33 848- The Trout Ordlnance- N otlce 595 Proclamattons Rules and Regulatlons 1950 849-850- 13e G am e O rdm ance- Appom tm ents 595 G ovt N otlce N o - extœ 8sl-x om m lttee on M ncan Tttxatzon- Appom lment 595 859- -1*11e M lnlmum W age (Amendment) Order 1950 379 852-854- -1Ye Courts Ordlnance -A ppolntm ents 595 860- The Defence (Contlol of Prlces) Regulatlons, 855-856 -* r Serwces Iacenslng 596 1945 379 857-858- *11e Inmugratlon (l-ontrol) Ordlnance 861- Thc Ptrbhc Travel and Ac ctss Roads O rdln- lgv - Appolntm ents, etc 596 allco-order 380 G eneral