I 'Ask Now of the Days That Are Passed'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FRIDAY 16Th NOVEMBER 2018

FAIZ INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL 16th – 18th November 2018 Alhamra Halls, Mall Road Lahore All events are free and open for all (Except for Tahira Syed, Tina Sani and Zia Mohyeddin performances) FRIDAY 16th NOVEMBER 2018 Hall 1 Hall 2 Gallery 4:00 – 4:45 pm ک یفی اور فی ض Shabana Azmi, Salima Hashmi (Adeel Hashmi & Mira Hashmi) Exhibition Opening 4:00 – 6:30 5:00-6:00 pm 5:00 pm Preparation Time Preparation Time 6:30 – 7:30 pm 6:00 – 7:00 pm زرد پتوں کا بن جو میرا د یس ہے Guests to be Seated Guests to be Seated 7:00 – 9:00 pm 7:30 – 9:00 pm بھ ُ کاﻻ م ینڈا یس یاد کی راہ گزر A Play by Ajoka Theatre An Evening with Tahira Syed Dedicated to Madeeha Gohar Note: Please download latest copy of the schedule nearer to the Festival as slight changes are expected. SATURDAY 17th NOVEMBER 2018 Time Hall 1 Hall 2 Hall 3 Gallery Adbi Baithak Exhibition Area Master Class on Screen Writing ت ت am 11:00 خواب کی ت لی کے ی چھے Javed Akhtar 12:00 pm (Adeel Hashmi) A performance by Sanjan Nagar Students Meet Uncle Sargam: A Conversation with نور کی لہر ق ق (Over My Shoulder (Alys Faiz ساق تا ر ص کوئی ر ِص ص تا صورت pm 12:00 Blurring the Boundaries: Imaging the Film Farooq Qaiser 12:45 pm Dance Performance Nayyar Rubab (Translator) Salima Hashmi, Imran Abas (Arshad Mehmood) (Lahore Grammar School) (Dr Sheeba Alam) (Mira Hashmi) َ Space, Place & Art: A Discussion on Art for Public ا تا لی ہوس والوں نے خو رسم چلی ہے ح ب عن یر د ت ت ب ی ِ س Spaces & People Patras Bukhari: A Friend, Diplomat, Teacher & Writer ,Natasha Jozi, Rabeya Jalil سمی دی وار صحافت م یں س ناست -

International National

IPRI Journal ISSN 1684-9787 e-ISSN 1684-9809 (HEC Recognised X-Category Journal) Editorial Board Chairperson: Ambassador Vice Admiral Khan Hasham Bin Saddique (R), HI (M) Members: Dr Fazal-ur-Rahman Prof. Dr Zafar Iqbal Cheema Prof. Dr Riaz Ahmad Sarah Siddiq Aneel Editorial Advisory Board International Mr Michael Krepon, Co-Founder and President Emeritus, Henry L. Stimson Center, Washington, D.C., USA. Ambassador (R) Nihal Rodrigo, Former Secretary of the Ministry of External Affairs, Sri Lanka and Former Secretary General SAARC, Sri Lanka. Dr Nischal N. Pandey, Executive Director, Centre for South Asian Studies (CSAS), Kathmandu, Nepal. Dr C. Raja Mohan, Director, Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore. Dr Saadet Gulden Ayman, Professor, Faculty of Political Science and International Relations, Istanbul University, Turkey. Dr Tariq Rauf, Principal, Global Nuclear Solutions, Vienna, Austria. Mr Zheng Ruixiang, Former Senior Research Fellow, China Institute of International Studies (CIIS), Beijing, China. National Dr Asad Zaman, Vice Chancellor, Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE), Islamabad, Pakistan. Prof. Dr Ijaz Hussain, Former Dean and Meritorious Professor, National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan. Prof. Dr Ishtiaq Ahmed, Professor Emeritus-Political Science, Visiting Professor, Government College University, Lahore, Pakistan. Dr Kamal Monnoo, Director, Samira Fabrics Private Limited, Lahore, and, Member Board of Governors, Islamabad Policy Research Institute (IPRI), Islamabad, Pakistan. Prof. Dr Pervaiz Iqbal Cheema, Dean, Faculty of Contemporary Studies, National Defence University (NDU), Islamabad, Pakistan. Ambassador (R) Riaz Muhammad Khan, Former Foreign Secretary, Government of Pakistan. Dr Shamim Akhtar, Former Chairperson, Department of International Relations, University of Karachi, Pakistan. -

Research and Development

Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT FACULTY OF ARTS & HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY Projects: (i) Completed UNESCO funded project ―Sui Vihar Excavations and Archaeological Reconnaissance of Southern Punjab” has been completed. Research Collaboration Funding grants for R&D o Pakistan National Commission for UNESCO approved project amounting to Rs. 0.26 million. DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE & LITERATURE Publications Book o Spatial Constructs in Alamgir Hashmi‘s Poetry: A Critical Study by Amra Raza Lambert Academic Publishing, Germany 2011 Conferences, Seminars and Workshops, etc. o Workshop on Creative Writing by Rizwan Akthar, Departmental Ph.D Scholar in Essex, October 11th , 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, University of the Punjab, Lahore. o Seminar on Fullbrght Scholarship Requisites by Mehreen Noon, October 21st, 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, Universsity of the Punjab, Lahore. Research Journals Department of English publishes annually two Journals: o Journal of Research (Humanities) HEC recognized ‗Z‘ Category o Journal of English Studies Research Collaboration Foreign Linkages St. Andrews University, Scotland DEPARTMENT OF FRENCH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE R & D-An Overview A Research Wing was introduced with its various operating desks. In its first phase a Translation Desk was launched: Translation desk (French – English/Urdu and vice versa): o Professional / legal documents; Regular / personal documents; o Latest research papers, articles and reviews; 39 Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development The translation desk aims to provide authentic translation services to the public sector and to facilitate mutual collaboration at international level especially with the French counterparts. It addresses various businesses and multi national companies, online sales and advertisements, and those who plan to pursue higher education abroad. -

Greenwich Earns the Most Exculsive Awards Banking Future Lies in Islamic Banking Muhammad Raza Head of Consumer Banking & Marketing Meezan Bank

Vol. XIII, Issue III - ISSN 2305-7947 Winter Semester 2013-2014 A Quarterly Periodical of Greenwich Earns the Most Exculsive Awards Banking Future Lies in Islamic Banking Muhammad Raza Head of Consumer Banking & Marketing Meezan Bank “Smart Thinking Can Lead To Success” Karim Ismail Teli Director, Orient Textile & Ibrahim Group of Companies Greenwich Alumnus Dear Readers, It gives us immense pleasure and joy to see G.Vision take its final shape at the com - pletion of another successful semester: Winter 2013-14.We can look at it and say that it’s an accomplished piece of work. This issue of G-Vision highlights an environ - ment of innovation and several significant events around Greenwich campus as we continue to evolve and grow. It is indeed a matter of great pride to be the editor of an issue where the cover story is all about the unwavering efforts, hard work and dedication of our Vice Chancel - lor and her entire team. Our cover story shines with Greenwich being the first ever EDITORIAL BOARD HEC recognized university to achieve the most prestigious awards namely The Brand of the Year Award and The Brand Scientist Award. Patron It is best said that “life is a succession of lessons which must be lived to be under - stood”. Life is an informal school. Each day we have an opportunity to learn. In this Ms Seema Mughal process of trial and error emerges the process of growth. Vice Chancellor Keeping this in mind I believe we have succeeded in putting together a well- Editor rounded, enjoyable memento for everybody. -

Year 2018-19

Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi List of Students Department Wise/State Wise/Gender Wise For Session Jul/2018 - Dec/2018,Jul/2018 - Jun/2019 AND Jan/2018 - Dec/2018 Run Date : 12/02/2020 Department :ALL Admission Type : ALL S.No. State/Country Gender S.No. Student ID Name Category Course 1 Andhra Pradesh Female 1 20175620 Gulafsha Fatima Muslim Women M.A./M.Sc. Mathematics( Self Finance) - II Yr. 2 20173501 Afreen Sheikh Muslim M.A.(Mass Communication)(Semester) - III Sem. 3 20185044 Aseya Fatima Muslim Women B.Tech.(Computer Engineering)(Semester) - I Sem. 4 20172098 Intifada P.B. Muslim Women M.A.(Convergent Journalism)(Semester Self Finance) - III Sem. Male 5 20182188 Qureshi Asif Ali Muslim OBC/Muslim ST M.A.(History)(Semester) - I Sem. 6 20182861 Ismail Shaik Arifulla Muslim B.A. (H) Arabic(Semester) - I Sem. 7 20181456 Mohammed Feroz Muslim M.A.(Conflict Analysis & Peace Building)(Semester) - I Sem. 8 20177481 Shaik Mohammed Muslim OBC/Muslim ST B.Tech.(Mechanical Muaviya Engineering)(Semester) - III Sem. 9 20181401 Abdul Khadar Muslim B.Ed. - I Yr. 10 20186322 Saidheeraj General M.A.(Economics)(Semester) - I Vayugundlachenchu Sem. 11 20157693 Mohammed Omar NRI ward under B.Tech.(Electrical Siddiqui Supernumeray category Engineering)(Semester) - VII Sem. 12 20159109 Venkata Saibabu General Ph.D.(Bio Science)(Semester) Thokala 13 20172111 Bhanu Prasad Palanati General M.Ed.(Special Education)(Semester) - III Sem. 14 20174688 Fakruddin Mohammed Muslim M.A.(Islamic Studies)(Semester) Ali Halaharvi - III Sem. 15 20177060 Abdul Sofiyan Muslim M.A.(Political Science)(Semester) - III Sem. 16 20148252 C. -

CV of Prof. Dr. Amra Raza

PROF. DR. AMRA RAZA Chairperson, Professor Department of English Language & Literature, University of the Punjab, Lahore E-mail: [email protected] Contact: 99231168 QUALIFICATIONS: 2008-Institution University of the Punjab, Lahore. Title of Research Thesis “Spatial Constructs in Alamgir Ph.D Hashmi‘s Poetry First Ph.D produced by the Department of English, University of the Punjab. 2001-Institution University of the Punjab, Lahore M.Phil Title of Research Thesis “Self Conscious Surveillance Strategies in Derek Walcott‘s Poetry (1948-84)” M.A. English 1989-Institution The University of Karachi Literature Merit First Class first position 1991-Institution The University of Karachi M.A. Linguistics Merit First Class First Position Research Thesis entitled ―The Feasibility of Establishing a Self Access Centre at Karachi University on the basis of the Self Access Centre at Agha Khan University School of Nursing, Karachi B.A. 1985-86 Institution St. Joseph’s College for Women, Karachi Merit First Division 1982-Institution St. Joseph’s College for Women, Karachi F.A. Merit First Division 1980-Institution: St. Joseph’s Convent School Karachi Matriculation Merit First Class Second Position (Humanities/Arts), Board of Secondary Education, Karachi. 1. American School – Bad Godesberg, Bonn, German Primary 2. British Embassy Preparatory School, Bonn, Germany Education 3. Nicolaus Cusanus Gymnasium, Bonn, Germany 1. National Jane Townsend Poetry Prize United States Cultural Centre, Karachi (1990) 2. Matric Certificate of Merit (General Group) Board of Secondary Education, Karachi First Class 2nd Position (1980) 3. First Class First Position (M.A. English Literature). Merit Certificate The University of Karachi (1989) 4. -

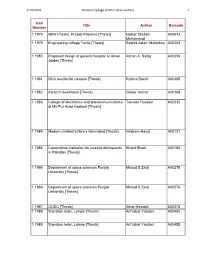

National Colege of Art Thesis List.Xlsx

4/16/2010 National College of Arts Library‐Lahore 1 Call Title Author Barcode Number 1 1975 MPA's hostel, Punjab Province [Thesis] Qaiser Ghulam A00573 Muhammad 1 1979 Engineering college Taxila [Thesis] Rashid Aslam Makhdum A00353 1 1980 Proposed design of general hospital at Aman Adnan A. Sadiq A00359 Jordan [Thesis] 1 1981 NCA residential campus [Thesis] Robina Bashir A00365 1 1982 Karachi Gymkhana [Thesis] Qaiser Ashrat A00368 1 1983 College of electronics and telecommunications Tanveer Hussain A00330 at Mir Pur Azad Kashmir [Thesis] 1 1984 Modern children's library Islamabad [Thesis] Nadeem Hayat A00121 1 1985 Correctional institution for juvenile delinquents Khalid Bhatti A00180 in Paksitan [Thesis] 1 1986 Department of space sciences Punjab Masud S Zaidi A00275 University [Thesis] 1 1986 Department of space sciences Punjab Masud S Zaidi A00276 University [Thesis] 1 1987 OGDC [Thesis] Athar Hussain A00375 1 1988 Sheraton hotel, Lahore [Thesis] Arif Iqbal Yazdani A00454 1 1988 Sheraton hotel, Lahore [Thesis] Arif Iqbal Yazdani A00455 4/16/2010 National College of Arts Library‐Lahore 2 1 1989 Engineering college Multan [Thesis] Razi-ud-Din A00398 1 1990 Islamabad hospital [Thesis] Nasir Iqbal A00480 1 1990 Islamabad hospital [Thesis] Nasir Iqbal A00492 1 1992 International Islamic University Islamabad Muhammad Javed A00584 [Thesis] 1 1994 Islamabad railway terminal: Golra junction Farah Farooq A00608 [Thesis] 1 1995 Community Facilities for Real People: Filling Ayla Musharraf A00619 Doxiadus Blanks [Thesis] 1 1995 Community Facilities -

INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS 1 H2061001 337672 2021 Morning Program

S.NO SEAT NO. ADM NO. YEAR PROGRAM NAME FATHER NAME CLASS SEMESTER TOTAL INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS 1 H2061001 337672 2021 Morning Program. ABDUL WAKEEL ABDUL GHANI KAKAR BA 1 2,100 2 H2061002 338695 2021 Morning Program. ADINA USMAN MUHAMMAD USMAN BA 1 2,100 3 H2061003 349183 2021 Morning Program. AHFAZ ALI ARIF ALI BA 1 2,100 4 H2061004 339903 2021 Morning Program. AHSAN ALI PEERANO BA 1 2,100 5 H2061005 340634 2021 Morning Program. AIMEN ADEEL ADEEL RIZWAN BA 1 2,100 6 H2061006 346514 2021 Morning Program. AQSA NAWAZ MOHAMMAD NAWAZ BA 1 2,100 7 H2061007 337823 2021 Morning Program. AQSA SALEEM SALEEM AKHTER GUL BA 1 2,100 8 H2061008 341719 2021 Morning Program. ARAAF BATOOL MUHAMMAD RAEES BA 1 2,100 9 H2061009 338454 2021 Morning Program. AREEBA AJAZ MUHAMMAD AJAZ BA 1 2,100 10 H2061010 347933 2021 Morning Program. AREEBA ATIQ MUHAMMAD ATIQ KHAN BA 1 2,100 11 H2061011 350461 2021 Morning Program. CHATAR SINGH SONO BA 1 2,100 12 H2061012 338281 2021 Morning Program. DUA BATOOL SYED ZIA ABBAS RIZVI BA 1 2,100 13 H2061013 337257 2021 Morning Program. EISHA SIDDIQUI JUNAID UL HAQ SIDDIQUI BA 1 2,100 14 H2061014 343420 2021 Morning Program. EMAN AFROZE AMIR ABBAS ANSARI BA 1 2,100 15 H2061015 336552 2021 Morning Program. HAFSA FATIMA HAFEEZ ULLAH BA 1 2,100 16 H2061016 337392 2021 Morning Program. HINA SIDDIQUI IMTIAZ AHMED SIDDIQUI BA 1 2,100 17 H2061017 346103 2021 Morning Program. IFFAH GUL ABDUL MAROOF BA 1 2,100 18 H2061018 336819 2021 Morning Program. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Prof. Kanwal Ameen (PhD) Vice Chancellor, University of Home Economics Lahore [email protected] -------------------------------------------------- Former: University of the Punjab (PU), Lahore-Pakistan. Director, Directorate of External Linkages (July 2018- May 2019), Chairperson, Department of Information Management (May 2009- May 2018) Chair, Doctoral Program Coordination Committee, PU (2013-2017) Chief Editor, Pakistan Journal of Information Management & Libraries (2009-2018) Founding Chair, South Asia Chapter, ASIS&T (Association for Information Science & Technology, USA; 2018) Professor/Scholar in Residence, University of Tsukuba, Japan (2013) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kanwal_Ameen https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=ZhuLbeYAAAAJ&hl=en https://pu-pk1.academia.edu/ProfDrKanwalAmeen; https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kanwal_Ameen https://pk.linkedin.com/in/kanwal-ameen-ph-d-761b9b15 Awards and Scholarships National ● Women Excellence Award 2020. UN Women Pakistan, PPIF, Govt. of Punjab ● Indigenous Post-Doctoral Supervision Award (2018-2019), Punjab Higher Education Commission (PHEC) ● Best Paper Awards in 2015/16 and 2017, Pakistan Higher Education Commission (HEC) ● Best Teacher Award 2010, HEC ● Best Teacher Awards, University of the Punjab ● Lifetime Academic Achievements Award 2009, Pakistan Library Association, ● HEC, PHEC, PU Travel grants to present papers at international conferences. International ● James Cretsos Leadership Award, 2019, Association of Information Science &Technology, (ASIS&T, USA), ● Best Paper Award, 2017, ASIS&T(USA) SIG III ● Emerald Award of Excellence for Outstanding Paper, 2009 ● A-LIEP Best Paper Award in 2006 ● FULBRIGHT AWARDS ○ Pre-Doc (2000-2001) University of Texas at Austin, USA ○ Post-Doc (2009-2010) University of Missouri, Columbia, USA ○ Fulbright Occasional Lecture Fund, 2010, North Carolina, USA ● Asian Library Leaders “Award for Professional Excellence – 2013, SRFLIS, Delhi, India. -

Resultcafexaminationsp2021.Pdf

THE INSTITUTE OF CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS OF PAKISTAN PRESS RELEASE April 29, 2021 Spring 2021 Result of Certificate in Accounting and Finance (CAF) The Council of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Pakistan is pleased to declare the result of the above examination held in March 2021: Candidates Passed-CAF Candidates Passed-CAF CRN Name Credited CRN Name Credited Paper(s) Paper(s) 046836 MUHAMMAD IRFAN ASIF KHOKHAR 078174 HAMZA SALEEM S/o MUHAMMAD ASIF KHOKHAR S/o MUHAMMAD SALEEM KHAN 056117 ALI AHMED ABBASI 078190 SYED IMRAN HAIDER S/o WAKEEL AHMED ABBASI S/o SYED ABID HUSSAIN 063526 UZAIR JAVEED 078759 MUHAMMAD BILAL PATHAN S/o JAVEED SALEEM S/o GHUFRAN AHMED PATHAN 066420 FARAZ NAEEM AHMED 079271 MUHAMMAD UBAID ASHRAF S/o NAEEM AHMED CHAUDHARY S/o RANA MUHAMMAD ASHRAF 068288 USMAN ALI 079584 CH. HAMDI TAHIR S/o PERVAIZ AHMAD S/o CHAUDHRY TAHIR AMIN 068343 FAIZA ASHIQ 079889 MOHSIN KHAN D/o ASHIQ ALI S/o ZULFIQAR ALI KHAN 069546 MUHAMMAD ASAD ULLAH FAROOQ 080002 MAHRUKH ALI S/o MUHAMMAD FAROOQ D/o ZULFQAR ALI 070000 ABUZAR SUBHANI 080328 ANAS TANVEER S/o MUNIR AHMAD S/o TANVEER HUSSAIN 071130 AMIR KHAN 080580 MUHAMMAD ADNAN ARSHAD S/o TILAWAT KHAN S/o MUHAMMAD ARSHAD 071198 FAHAD BIN TARIQ 080632 AHSAN SALMAN S/o TARIQ MEHMOOD S/o MUHAMMAD SALMAN 072264 GHULAM FATIMA 081229 AMMARA ASLAM D/o YAQOOB AHMAD FAROOQI D/o MUHAMMAD ASLAM 072552 IQRA GUL AFSHA 081460 JALAL KHAN D/o GUL SHER KHAN S/o SHAHEEN ULLAH 074194 HAROON KHAN 081473 SARAH ARSHAD S/o ILYAS KHAN D/o ARSHAD SALEEM 074332 SABA IFTIKHAR 082093 MUHAMMAD ARSALAN D/o IFTIKHAR -

Name Currency Amount Country Transdate Sheikh Faisal Hassan

Donations for PM and CJ Fund for Diamer Bhasha and Mohmand Dam Fund through Debit/Credit Card on SBP website as of 01-Feb- 2019 06:15 PM using MCB Payment Gateway. Name Currency Amount Country TransDate Sheikh Faisal Hassan USD 50 USA 2/1/2019 8:41 Javed Iqbal PKR 100000 USA 2/1/2019 6:20 Shafia USD 20 Canada 1/31/2019 21:05 Mirza Raheel Baig PKR 500 Not Mentioned 1/31/2019 20:51 Naveed iqbal PKR 31600 Italy 1/31/2019 17:44 Syed Saud Alam PKR 15000 Australia 1/31/2019 14:49 Ali Mahar PKR 10000 Pakistan 1/31/2019 13:15 Mahmood Kamal PKR 92 Pakistan 1/31/2019 10:51 Sajid Farooq PKR 1000 USA 1/31/2019 8:29 Abdullah PKR 1000 Unied Arab Emirates 1/31/2019 6:30 Sulman Ahmed PKR 18250 United Kingdom 1/31/2019 4:34 Janu Januuz PKR 30 Pakistan 1/31/2019 3:01 Janu Januuz PKR 30 Pakistan 1/31/2019 2:58 Janu Januuz PKR 30 Pakistan 1/31/2019 2:52 Janu Januuz PKR 30 Pakistan 1/31/2019 0:59 Janu Januuz PKR 30 Pakistan 1/31/2019 0:53 Janu Januuz PKR 30 Pakistan 1/31/2019 0:42 Janu Januuz PKR 30 Pakistan 1/31/2019 0:27 Faizan Malik PKR 5160 Ireland 1/30/2019 23:25 Janu Januuz PKR 30 Pakistan 1/30/2019 23:12 Janu Januuz PKR 30 Pakistan 1/30/2019 22:46 Muhammad Tahir Imam PKR 8000 Not Mentioned 1/30/2019 20:30 Muhammad Neaman Siddique USD 25 United States 1/30/2019 20:04 muhammad imran shahid PKR 2000 uae 1/30/2019 15:25 Muhammad Sufyan Shoaib PKR 15000 United Arab Emirates 1/30/2019 14:44 Bilal Masaud USD 50 Saudi Arabia 1/30/2019 13:59 Ghazi Murtaza USD 10 UK 1/30/2019 13:26 Nazia Bi USD 15 United Kingdom 1/30/2019 13:03 Usamah Bin Azfar USD 100 Saudi -

Kamran Bashir [email protected]

Kamran Bashir [email protected] EDUCATION 2012-2018 PhD, Department of History University of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada Dissertation Andrew Rippin (2012-2016) Supervisors Derryl Maclean & Neilesh Bose (2016-18) 2014-2016 Graduate Certificate in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education Dept. of Educational Psychology / Learning & Teaching Centre University of Victoria Fall 2013 Doctoral Coursework in South Asian Islam Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada 2010-2012 MA in Muslim Cultures, London, United Kingdom Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations Affiliated with The Aga Khan University, Pakistan 2009-2010 Diploma in Arabic Language and Literature Department of Languages, Oriental College University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan 1992-1994 MBA, Institute of Business Administration Punjab University, Lahore, Pakistan ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2019- Assistant Professor Department of Liberal Arts Beaconhouse National University Lahore, Pakistan 2017-2018 Sessional Instructor Department of Humanities Camosun College Victoria, British Columbia, Canada Kamran Bashir 2017-2018 Instructor Division of Continuing Studies (Humanities) University of Victoria Victoria, British Columbia, Canada 2016-2017 Sessional Instructor Department of History University of Victoria Victoria, British Columbia, Canada TEACHING INTERESTS Formative Period of Islam Modern South Asia and Islam Historiography / Philosophy of History Survey of Islamic History History of South Asia Qur’anic Studies Cultural Anthropology World Religions INSTITUTIONAL AFFILIATIONS/ RESEARCH COLLABORATIONS Summer 2018 Collaborated with Sheila Yeoman on a book project, involving archival research, that is aimed at writing a biography of Annie Gale (1876-1970), the first woman alderman in the British Empire. 2017-2018 Research Associate Centre for Global Studies, University of Victoria 2015-16 Research Assistant to Dr.