Pamukkale Journal of Sport Sciences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2821 Bursaspor Kulübü Dernegi V

Tribunal Arbitral du Sport Court of Arbitration for Sport Arbitration CAS 2012/A/2821 Bursaspor Kulübü Dernegi v. Union des Associations Européennes de Football (UEFA), award of 10 July 2012 (operative part of 22 June 2012) Panel: Mr Manfred Nan (The Netherlands), President; Prof. Ulrich Haas (Germany); Mr Stuart McInnes (United Kingdom) Football Disciplinary sanction due to violation of the UEFA Club Licensing and Financial Fair Play Regulations Mistakes in the interpretation of the events and/or the law by the first-instance body and CAS’ power of review Aim of the UEFA CL&FFP Regulations Monitoring process and requirements Notion of “payables” Disclosure obligations for clubs under the UEFA CL&FFP Regulations Assessment of the sanctions under the UEFA CL&FFP Regulations 1. Pursuant to Article R57 CAS Code, which grants a CAS panel power to review the facts and the law, and CAS jurisprudence, any prejudice suffered by a party before the first- instance body has been cured by virtue of this appeal, in which the party has been able to present its case afresh. Therefore, the CAS panel does not need to examine whether the alleged mistakes and errors in the interpretation of the events and/or the law have been established. 2. The UEFA CL&FFP Regulations have been enacted by the UEFA Executive Committee on the basis of Article 50 par. 1 bis of the UEFA Statutes, which empowers the UEFA Executive Committee to draw up regulations governing the conditions of participation in and the staging of UEFA competitions. Compliance with these rules is a condition of entry into club competitions such as the UEFA Champions League and UEFA Europa League. -

![Taraftarium24!!!]***Sivasspor - Beşiktaş Canlı İzle Maçı Yayını 17-08-2019 Süper Lig Bein Sports 1 HD](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0142/taraftarium24-sivasspor-be%C5%9Fikta%C5%9F-canl%C4%B1-izle-ma%C3%A7%C4%B1-yay%C4%B1n%C4%B1-17-08-2019-s%C3%BCper-lig-bein-sports-1-hd-170142.webp)

Taraftarium24!!!]***Sivasspor - Beşiktaş Canlı İzle Maçı Yayını 17-08-2019 Süper Lig Bein Sports 1 HD

~*[(((Taraftarium24!!!]***Sivasspor - Beşiktaş Canlı İzle Maçı Yayını 17-08-2019 Süper Lig beIN Sports 1 HD Sivasspor - Beşiktaş Maçı Canlı Anlatım Olarak İzle - Spor Haberleri Sivasspor - Beşiktaş maçını canlı olarak Stadyum'dan takip edebilirsiniz. İşte Sivasspor - Beşiktaş maçının canlı anlatımı ve maça dair son istatistikler... Sivasspor Beşiktaş Maçı Canlı Izle Haberleri - Son Dakika Yeni ... Sivasspor Beşiktaş Maçı Canlı Izle haberi sayfasında en son yaşanan sivasspor beşiktaş maçı canlı izle gelişmeleri ile birlikte geçmişten bugüne CNN Türk'e ... En çok okunan haberler Canlı Maç İzle. Tüm spor karşılaşmalarını, şifreli tüm spor kanallarını JestBahis farkıyla ücretsiz olarak hd kalitede canlı maç izlemek için JestYayın.com'u tercih ... Sivasspor - Beşiktaş maçı canlı anlatım - Maç özeti, son dakika ... - Sporx Tarih: 18 Ağustos 2019 Pazar 03:00. Lig: Süper Lig. Sivasspor -. Beşiktaş ... MAÇ İSTATİSTİĞİ. KARŞILAŞTIRMA. Bu maça ait canlı anlatım bulunmamaktadır. Sivasspor Beşiktaş GOLLERİ İZLE, Beşiktaş Sivasspor maçı tüm ... 22 Nis 2019 - Sivasspor Beşiktaş maçı özet ve golleri izle!Beşiktaş, Spor Toto Süper Lig'in 29. haftasında deplasmanda Demir Grup Sivasspor ile karşılaştı. ++BJK++Besiktas.,Sivasspor,.Macini,.izle - Read the Docs Demir Grup Sivasspor-Beşiktaş - Sabah canlı skor. ... 19.08.2018 | Büyükşehir Belediye Erzurumspor - Beşiktaş 19.08.2018 | Akhisarspor - Çaykur Rizespor Sivasspor Beşiktaş Süper Lig maçı ne zaman, saat kaçta? - Son ... 1 gün önce - Beşiktaş Süper Lig ilk hafta mücadelesi kapsamında Sivasspor deplasmanına konuk oluyor. Kadrosuna kattığı yeni isimlerle sezona hızlı bir ... Sivasspor Beşiktaş maçı ne zaman? Sivasspor BJK maçı saat kaçta ... 1 gün önce - Sivasspor Beşiktaş maçı ne zaman saat kaçta sorusu siyah beyazlı ... Beşiktaş da sezonun ilk haftasında Sivaspor deplasmanında 3 puan ... Sivasspor Beşiktaş maçı ne zaman? - Yeni Şafak 2 gün önce - Demir Grup Sivasspor, Süper Lig'in ilk haftasında 17 Ağustos Cumartesi günü sahasında Beşiktaş ile yapacağı karşılaşmanın hazırlıklarını .. -

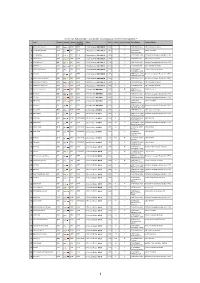

The-KA-Club-Rating-2Q-2021 / June 30, 2021 the KA the Kick Algorithms ™

the-KA-Club-Rating-2Q-2021 / June 30, 2021 www.kickalgor.com the KA the Kick Algorithms ™ Club Country Country League Conf/Fed Class Coef +/- Place up/down Class Zone/Region Country Cluster Continent ⦿ 1 Manchester City FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,928 +1 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ⦿ 2 FC Bayern München GER GER � GER UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,907 -1 UEFA Central DACH Countries Western Europe ≡ ⦿ 3 FC Barcelona ESP ESP � ESP UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,854 UEFA Iberian Zone Romance Languages Europe (excl. FRA) ⦿ 4 Liverpool FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,845 +1 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ⦿ 5 Real Madrid CF ESP ESP � ESP UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,786 -1 UEFA Iberian Zone Romance Languages Europe (excl. FRA) ⦿ 6 Chelsea FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,752 +4 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ≡ ⦿ 7 Paris Saint-Germain FRA FRA � FRA UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,750 UEFA Western France / overseas territories Continental Europe ⦿ 8 Juventus ITA ITA � ITA UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,749 -2 UEFA Central / East Romance Languages Europe (excl. FRA) Mediterranean Zone ⦿ 9 Club Atlético de Madrid ESP ESP � ESP UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,676 -1 UEFA Iberian Zone Romance Languages Europe (excl. FRA) ⦿ 10 Manchester United FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,643 +1 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ⦿ 11 Tottenham Hotspur FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,628 -2 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ≡ ⬇ 12 Borussia Dortmund GER GER � GER UEFA 2 Primary High ★★★★★ 1,541 UEFA Central DACH Countries Western Europe ≡ ⦿ 13 Sevilla FC ESP ESP � ESP UEFA 2 Primary High ★★★★★ 1,531 UEFA Iberian Zone Romance Languages Europe (excl. -

Uefa Europa League

UEFA EUROPA LEAGUE - 2017/18 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Konya Büyükşehir Belediyesi Stadyumu - Konya Thursday 28 September 2017 Konyaspor 19.00CET (20.00 local time) Vitória SC Group I - Matchday 2 Last updated 26/09/2017 12:06CET Fixtures and results 2 Legend 5 1 Konyaspor - Vitória SC Thursday 28 September 2017 - 19.00CET (20.00 local time) Match press kit Konya Büyükşehir Belediyesi Stadyumu, Konya Fixtures and results Konyaspor Date Competition Opponent Result Goalscorers 13/08/2017 League Trabzonspor AŞ (A) L 1-2 Fofana 2 21/08/2017 League Gençlerbirliği SK (H) W 3-0 Araz 24, 53, Skubic 43 27/08/2017 League İstanbul Başakşehir (A) L 1-2 Skubic 88 09/09/2017 League Alanyaspor (H) L 0-2 14/09/2017 UEL Olympique de Marseille (A) L 0-1 18/09/2017 League Beşiktaş JK (A) L 0-2 23/09/2017 League Akhisar Belediyespor (H) W 2-0 Ömer Ali Şahiner 17, Friday 73 28/09/2017 UEL Vitória SC (H) 01/10/2017 League Yeni Malatyaspor (A) 14/10/2017 League Galatasaray AŞ (H) 19/10/2017 UEL FC Salzburg (H) 22/10/2017 League Kayserispor (A) 28/10/2017 League Osmanlıspor (H) 02/11/2017 UEL FC Salzburg (A) 05/11/2017 League Sivasspor (A) 18/11/2017 League Antalyaspor (H) 23/11/2017 UEL Olympique de Marseille (H) 26/11/2017 League Kasımpaşa SK (A) 03/12/2017 League Bursaspor (H) 07/12/2017 UEL Vitória SC (A) 11/12/2017 League Kardemir Karabükspor (H) 18/12/2017 League Göztepe Izmir (A) 23/12/2017 League Fenerbahçe SK (H) 21/01/2018 League Trabzonspor AŞ (H) 28/01/2018 League Gençlerbirliği SK (A) 04/02/2018 League İstanbul Başakşehir (H) 11/02/2018 League Alanyaspor -

Rivalry in the Football Industry and Its Impact on the Stock Prices of Listed Football Clubs Master Thesis Finance

Rivalry in the football industry and its impact on the stock prices of listed football clubs Master Thesis Finance BY W.J.Tankink Supervisor: J.H. von Eije Groningen, January 11, 2018 University of Groningen Faculty of Economics and Business MSc Finance Words: 9381 Abstract Rivalry in the football industry is examined in this paper as it analyses rivalry effects on stock price performance of football clubs. It does not matter which sport is exercised and at what level, rivalry among clubs is one of the main sources of attractiveness of a league. The rivalry among football clubs leads to a positive “mood” in case the rival loses and leads to a negative “mood” in case the rival has a for them positive match result. It is hypothesised that these emotions due to the performance of the period rival affect the stock price performance of the focal football club. This study shows that there is evidence that the results of the period rival can have an impact on the investment decisions of club supporters. Keywords: Rivalry, Period Rivalry, Football clubs, European Football, Stock performance 2 1. Introduction Football, or what they call it in the United States soccer, is a well-known sport exercised all around the world. It all started in 1887. From then on it was allowed by the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) to recruit football players as an individual football club. This was the start of, what is familiar to us now as, professional football. In other words, money made its entrance here and the role of money has increased a lot since then (Dobson and Goddard, 1998). -

Moneyball in the Turkish Football League -.: Scientific Press

Journal of Applied Finance & Banking, vol. 3, no. 4, 2013, 1-12 ISSN: 1792-6580 (print version), 1792-6599 (online) Scienpress Ltd, 2013 Moneyball in the Turkish Football League: A Stock Behavior Analysis of Galatasaray and Fenerbahce Based on Information Salience Caner Özdurak1 and Veysel Ulusoy2 Abstract Football clubs listed on Istanbul Stock Exchange suggests an interesting way of testing stock price behaviors to different types of news about both sportive success related and non-sports related events. Strong football club stock price reactions to surprising game results and the lack of reaction to betting odds is related with the dominated structure of Turkish Football League by the big four; Galatasaray (GS), Fenerbahce (FB), Besiktas (BJK) and Trabzonspor (TS). Coherent with this idea we conclude that GS and FB stocks react strongly to unexpected game results and derby matches. Other local league match wins do not have such an impact on stock prices. Moreover especially for FB related news rather than game results such as match-fixing case explain most of the price volatilities of the sport stocks. There is also some limited support for the notion that GS and FB stock prices are more affected by the bad news compared to good news. JEL classification numbers: B23, G02, G17, L83 Keywords: Galatasaray, Fenerbahce, Istanbul Stock Exchange Sport Index, Information Salience, Sports Economics, GARCH, Time Series. 1 Introduction Football’s, so called Soccer in the USA, recent commercialization is producing an important research field that is not so even at the level that counts-the clubs that create the talent and dazzle the crowds introduced the modern gladiators of our age to us. -

3256 Fenerbahçe Spor Kulübü V

Tribunal Arbitral du Sport Court of Arbitration for Sport Arbitration CAS 2013/A/3256 Fenerbahçe Spor Kulübü v. Union des Associations Européennes de Football (UEFA), award of 11 April 2014 (operative part of 28 August 2013) Panel: Mr Manfred Nan (the Netherlands), President; Prof. Ulrich Haas (Germany); Mr Rui Botica Santos (Portugal) Football Disciplinary sanction against a club for match-fixing Definitions of “match-fixing” Res judicata Ne bis in idem Competence of UEFA to instigate disciplinary proceedings in national match-fixing cases Standard of proof in match-fixing cases Liability for match-fixing of a legal entity Proportionality of the sanction 1. In its “classic” sense, match-fixing involves a party directly or indirectly influencing or trying to influence the outcome of matches to its own benefit. In a more “modern” sense, match-fixing involves third parties (i.e. criminal organisations) attempting to influence the result of a match by inducing athletes, referees or clubs to act in a certain way during a match. The third party fixing the match is not necessarily interested in the outcome of the match, but is interested in certain events to occur on which bets can be placed, in order to make profit. Although third parties are not involved in “classic” match-fixing, the latter is in fact just as treacherous to the integrity of sport, if not more, as match-fixing in its “modern” context. 2. The procedural concept of res iudicata has two elements: 1) the so-called “Sperrwirkung” (prohibition to deal with the matter = ne bis in idem), the consequence of this effect being that if a matter (with res iudicata) is brought again before the judge, the latter is not even allowed to look at it, but must dismiss the matter (insofar) as inadmissible; and 2) the so-called “Bindungswirkung” (binding effect of the decision), according to which the judge in a second procedure is bound to the outcome of the matter decided in res iudicata. -

“Yer-Altı-Üstü”

GÜNCEL BASIN SPOR Türk Sezonu Hüseyin Latif Berk Mansur 9 ay süreden sonra 6 Nisan 6. yıldönümünü kutlayan Delipınar 2010’da, Fransa’da Türk Mevsimi Türkiye’nin tek Fransızca gaze- Küçük takımlar 4 etkinliklerinin kapanışı Versaille tesi Aujourd’hui La Turquie’nin büyükleri yutabilir Kraliyet Opera Sarayı’nda, Genel Yayın Yönetmeni Hüseyin mi? Maçlarıyla hayatı Avrupa ve Osmanlı saray Latif, gazetenin yayın tarihçesi durduran futbolda bu müziklerinden oluşan eserinin ve frankofoniyle ilgili fikirlerini kez 4 büyükleri zorlayan gösterimiyle gerçekleştirildi. bizimle paylaştı. Bursaspor ele alındı. Sayfa 2 Sayfa 4 Sayfa 3 Supplément gratuit au numéro 61, Mai 2010 d’Aujourd’hui la Turquie No ISSN : 1305-6476 İş Sanat Mayıs ayında Ayla Aksungur Heykel Sergisi İş Sanat, Mayıs ayında da etkinlikleriyle bir masal sarayında başlayan İstanbul ef- sanatseverlerle bir çok ismi buluşturuyor. saneleri, tiyatro dünyasının duayeni Müş- Efsaneler şehri İstanbul, aşı- fik Kenter’in seslendireceği “Yer-Altı-Üstü” ğı olan onlarca şairin Müşfik usta şairlerin kaleminden Heykeltıraş ve akademisyen kimliğiyle nedeninin başlıca motiflerden birisi ola- Kenter’in sesinde hayat bula- çıkma şiirlerle dile geliyor. çağdaş Türk heykel sanatı içinde önemli rak kabul ediliyor. Doğa, yaşam ve insan cak şiirleri ve usta bestekârların Son 10 yıldır sanatın çekim bir yere sahip Ayla Aksungur’ un üçüncü arasındaki içiçe geçmişliğin yanısıra, yer birbirinden değerli solistlerin merkezi haline gelen İş Sa- kişisel sergisi, 6 – 30 Nisan 2010 tarihleri ile gök arasındaki bağlantıyı temsil eden yorumlayacağı şarkılarıyla İş nat, sezonu Daniel Binelli’nin arasında Evin Sanat Galerisi’nde sanat- bir varlık olarak dikkat çeken ağaç miti, Sanat’ta dile geliyor. “Ah Gü- müzik direktörlüğü ve Clau- severlerle buluştu. -

Ulusal Ligler Uzantıları

ulusal ligler ve uzantıları 1988-1989 – 1997-1998 erdinç sivritepe turkish-soccer.com 1 dördüncü on yıl Bu on yıllık döneme genel olarak bakılınca ilk göze çarpan şey takımların çeşitli nedenlerle ligleri tamamlayamamaları ve liglerden çekilmeler oluyor. --1. Lig takımı Samsunspor ölümcül trafik kazası nedeni ile sezon sonuna dek izinli sayıldı – 1988-1989 --Cizre terör olayları nedeni ile son yedi maçını oynayamadı ve izinli sayıldı - 1989-1990 --Büyük Salatspor 4. Hafta sonrasında liglerden çekildi - 1989-1990 --Adana Gençlerbirliği 7. Hafta sonrası liglerden çekildi – 1992-1993 --Cizre 15. Hafta sonrası liglerden çekildi – 1993-1994 --TEK 12 Mart 8. Hafta sonrası liglerden çekildi – 1993-1994 --DHMİ ligler başlamadan liglerden çekildi – 1995-1996 --Edirne DSİ ligler başlamadan liglerden çekildi – 1996-1997 --Kozan Belediye ölümcül trafk kazası nedeni ile sezon sonuna dek izinli sayıldı – 1997-1998 1. Lig - Bu dönemde Beşiktaş ve Galatasaray dört, Fenerbahçe iki şampiyonluk elde ederken Trabzonspor şampiyonluk elde edemedi. Galatasaray Fenerbahçe den sonra 10 kez şampiyon olan takım olurken aralarındaki farkı da azalttı. Özel televizyon kanalında maç yayını yapıldı Gece maçları ve Cuma geceleri de maçlar oynanmaya başladı. 2. Lig - Bursaspor genç takımı şampiyon olunca ayni kulübün iki takımının da ayni ligde oynayamaması nedeni ile 1. Lige alınmadı. Genç takımların liglerde oynaması yasaklandı Beş gruplu ve 3 aşamalı lig yapısı denendi ve beğenildi. Bu yapı futbolumuza Play-off yapısını da getirdi 2. Lig takımları Balkan Kupasında oynamaya başladı ancak bu karar kupanın sonlandırılması nedeni ile uzun süreli olmadı 3. Lig - Takım sayıları 130-166 arasında devamlı değişti. Liglerde yepyeni isimler oynamaya başladı 3. Lige Çıkma - Türkiye Amatör Birinciliklerinde dereceye giren takımlar 3. -

Uefa Europa League

UEFA EUROPA LEAGUE - 2017/18 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Stadion Salzburg - Salzburg Thursday 2 November 2017 21.05CET (21.05 local time) FC Salzburg Group I - Matchday 4 Konyaspor Last updated 20/10/2017 13:03CET Previous meetings 2 Legend 3 1 FC Salzburg - Konyaspor Thursday 2 November 2017 - 21.05CET (21.05 local time) Match press kit Stadion Salzburg, Salzburg Previous meetings Head to Head UEFA Europa League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Gulbrandsen 5, 19/10/2017 GS Konyaspor - FC Salzburg 0-2 Konya Dabbur 80 Home Away Final Total Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L GF GA FC Salzburg 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 2 0 Konyaspor 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 2 FC Salzburg - Record versus clubs from opponents' country UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Raul Meireles 8, Sow 3-1 06/08/2013 QR3 Fenerbahçe SK - FC Salzburg Istanbul 17, Webó 34; Jonatan agg: 4-2 Soriano 4 Alan 68; Cristian 90+5 31/07/2013 QR3 FC Salzburg - Fenerbahçe SK 1-1 Salzburg (P) UEFA Cup Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers 2-0 29/09/1976 R1 Adanaspor AŞ - FC Salzburg Adana Ertürk 2, Sener 88 agg: 2-5 Schwarz 2, 37 (P), 61, 15/09/1976 R1 FC Salzburg - Adanaspor AŞ 5-0 Salzburg Haider 58, 81 Konyaspor - Record versus clubs from opponents' country Konyaspor have not played against a club from their opponents' country Home Away Final Total Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L GF GA FC Salzburg 2 1 1 0 3 1 0 2 0 0 0 0 5 2 1 2 9 6 Konyaspor 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 2 2 FC Salzburg - Konyaspor Thursday 2 November -

Sundays Longlist Overlayimage

Friday Longlist Match Betting Match Betting LIST 1 LIST 2 LIST 3 LIST 1 - STAKE HOME DRAW AWAY H | D | A H | D | A H | D | A 0.05 0.10 0.20 0.40 0.50 1.00 00:00 Sunday 27th December 27th December 2.00 4.00 5.00 10.00 20.00 40.00 12:00 8/11 LEEDS 3/1 BURNLEY 10/3 14:15 13/10 WEST HAM 23/10 BRIGHTON 21/10 16:30 1/8 LIVERPOOL 15/2 WEST BROM 18/1 19:15 13/5 WOLVES 11/5 TOTTENHAM 23/20 50.00 100.00 200.00 400.00 500.00 VOID 13:30 7/4 UTRECHT 11/4 AZ ALKMAAR 5/4 12:30 11/10 ROYAL ANTWERP 9/4 CHARLEROI 23/10 15:00 2/7 GENK 9/2 WAASL' BEV' 15/2 LIST 1 - BET TYPE 17:15 8/13 ANDERLECHT 3/1 BEERSCHOT VA 18/5 19:45 4/7 MECHELEN 14/5 MOUSCRON 9/2 Singles Doubles Trebles 4-Folds 10:30 15/8 GAZISEHIR GAZIANTE 23/10 ALANYASPOR 13/10 13:00 11/8 DENIZLISPOR 21/10 ANKARAGUCU 19/10 13:00 4/7 MALATYASPOR 14/5 ERZURUM BB 9/2 5-Folds 6-Folds 7-Folds 8-Folds 16:00 1/2 ISTANBUL BASAKSEH 10/3 KASIMPASA 9/2 11:30 6/4 REGGIANA 2/1 REGGINA 7/4 14:00 10/3 ASCOLI 23/10 SPAL 4/5 9-Folds 10-Folds Accumulator 14:00 5/6 CHIEVO 23/10 CITTADELLA 16/5 14:00 21/20 COSENZA CALCIO 11/5 PISA 5/2 14:00 2/1 ENTELLA 19/10 PESCARA 7/5 14:00 13/8 FROSINONE 2/1 PORDENONE 17/10 14:00 6/10 LECCE 14/5 VICENZA 19/5 LIST 2 - STAKE 14:00 1/1 VENEZIA 21/10 SALERNITANA 14/5 0.05 0.10 0.20 0.40 0.50 1.00 17:00 6/4 BRESCIA 21/10 EMPOLI 17/10 20:00 5/2 CREMONESE 19/10 MONZA 23/20 15:00 7/4 FAMALICAO 2/1 GIL VICENTE 13/8 2.00 4.00 5.00 10.00 20.00 40.00 15:00 1/1 NACIONAL 9/4 TONDELA 11/4 17:30 7/4 FARENSE 21/10 PACOS DE FERREIRA 8/5 20:00 13/2 BELENENSES 16/5 SP LISBON 2/5 50.00 100.00 200.00 -

Home Home Away Away -- Giresunspor +0.5 1.72 1.73 2.85 Home 18 Foggia 0/+0.5 1.81 1.78 2.67 Home 1 Istanbul Basaksehir -0.5 1.98

26 / 12 / 2017 17:00 Home Asian Handicap Over/Under Home Asian Handicap Over/Under Kick-off Kick-off Matches Standing Win/Draw/Win Matches Standing Win/Draw/Win time Over/ time Over/ Handicap Odds Total Handicap Odds Total Away Under Away Under -- Giresunspor +0.5 1.72 Over2.5 1.73 2.85 Home 18 Foggia 0/+0.5 1.81 Over2.5/3 1.78 2.67 Home 27 / 12 29 / 12 TURC 1 Istanbul Basaksehir -0.5 1.98 Under2.5 1.87 1.93 Away ITA2 2 Frosinone 0/-0.5 1.89 Under2.5/3 1.82 2.07 Away 20:00 03:30 7008 3.22 Draw 9008 3.13 Draw 5 Kayserispor -0.5 1.85 Over2.5 1.77 1.78 Home 1 Palermo -0.5/-1 1.91 Over2/2.5 1.68 1.63 Home 27 / 12 29 / 12 TURC 15 Antalyaspor +0.5 1.85 Under2.5 1.83 3.27 Away ITA2 11 Salernitana +0.5/+1 1.79 Under2/2.5 1.92 4 Away 21:30 03:30 7009 3.22 Draw 9009 3.21 Draw 16 Konyaspor 0 1.86 Over2.5 1.83 2.33 Home 13 Perugia 0 1.73 Over2.5 1.86 2.23 Home 27 / 12 29 / 12 TURC 7 Trabzonspor 0 1.84 Under2.5 1.77 2.3 Away ITA2 5 Empoli 0 1.97 Under2.5 1.74 2.57 Away 23:30 03:30 7010 3.18 Draw 9010 2.93 Draw 12 Oostende 0 2.02 Over2.5 1.87 2.68 Home 12 Pescara 0/-0.5 1.76 Over2.5/3 1.8 1.92 Home 28 / 12 29 / 12 BEL1 10 Genk 0 1.78 Under2.5 1.83 2.33 Away ITA2 8 Venezia 0/+0.5 1.94 Under2.5/3 1.8 2.9 Away 01:00 03:30 8002 3.28 Draw 9011 3.22 Draw 3 Fenerbahce -1.5/-2 1.74 Over3/3.5 1.88 1.11 Home 21 Pro Vercelli 0/+0.5 1.74 Over2/2.5 1.8 2.75 Home 28 / 12 29 / 12 TURC -- Istanbulspor +1.5/+2 1.96 Under3/3.5 1.72 9.8 Away ITA2 7 Cittadella 0/-0.5 1.96 Under2/2.5 1.8 2.13 Away 01:30 03:30 8011 5.6 Draw 9012 2.88 Draw 4 Parma -0.5 1.76 Over2 1.76 1.68