Plant Vascular Development: from Early Specification to Differentiation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska United States Forest Service R10-RG-182 Department of Alaska Region June 2010 Agriculture Ferns abound in Alaska’s two national forests, the Chugach and the Tongass, which are situated on the southcentral and southeastern coast respectively. These forests contain myriad habitats where ferns thrive. Most showy are the ferns occupying the forest floor of temperate rainforest habitats. However, ferns grow in nearly all non-forested habitats such as beach meadows, wet meadows, alpine meadows, high alpine, and talus slopes. The cool, wet climate highly influenced by the Pacific Ocean creates ideal growing conditions for ferns. In the past, ferns had been loosely grouped with other spore-bearing vascular plants, often called “fern allies.” Recent genetic studies reveal surprises about the relationships among ferns and fern allies. First, ferns appear to be closely related to horsetails; in fact these plants are now grouped as ferns. Second, plants commonly called fern allies (club-mosses, spike-mosses and quillworts) are not at all related to the ferns. General relationships among members of the plant kingdom are shown in the diagram below. Ferns & Horsetails Flowering Plants Conifers Club-mosses, Spike-mosses & Quillworts Mosses & Liverworts Thirty of the fifty-four ferns and horsetails known to grow in Alaska’s national forests are described and pictured in this brochure. They are arranged in the same order as listed in the fern checklist presented on pages 26 and 27. 2 Midrib Blade Pinnule(s) Frond (leaf) Pinna Petiole (leaf stalk) Parts of a fern frond, northern wood fern (p. -

The Origin of Alternation of Generations in Land Plants

Theoriginof alternation of generations inlandplants: afocuson matrotrophy andhexose transport Linda K.E.Graham and LeeW .Wilcox Department of Botany,University of Wisconsin, 430Lincoln Drive, Madison,WI 53706, USA (lkgraham@facsta¡.wisc .edu ) Alifehistory involving alternation of two developmentally associated, multicellular generations (sporophyteand gametophyte) is anautapomorphy of embryophytes (bryophytes + vascularplants) . Microfossil dataindicate that Mid ^Late Ordovicianland plants possessed such alifecycle, and that the originof alternationof generationspreceded this date.Molecular phylogenetic data unambiguously relate charophyceangreen algae to the ancestryof monophyletic embryophytes, and identify bryophytes as early-divergentland plants. Comparison of reproduction in charophyceans and bryophytes suggests that the followingstages occurredduring evolutionary origin of embryophytic alternation of generations: (i) originof oogamy;(ii) retention ofeggsand zygotes on the parentalthallus; (iii) originof matrotrophy (regulatedtransfer ofnutritional and morphogenetic solutes fromparental cells tothe nextgeneration); (iv)origin of a multicellularsporophyte generation ;and(v) origin of non-£ agellate, walled spores. Oogamy,egg/zygoteretention andmatrotrophy characterize at least some moderncharophyceans, and arepostulated to represent pre-adaptativefeatures inherited byembryophytes from ancestral charophyceans.Matrotrophy is hypothesizedto have preceded originof the multicellularsporophytes of plants,and to represent acritical innovation.Molecular -

The Genomics of Wood Formation in Angiosperm Trees

The Genomics of Wood Formation in Angiosperm Trees Xinqiang He and Andrew T. Groover Abstract Advances in genomic science have enabled comparative approaches that can evaluate the evolution of genes and mechanisms underlying phenotypic traits relevant to angiosperm forest trees. Wood formation is an excellent subject for com- parative genomics, as it is an ancestral trait for angiosperms and has undergone significant modification in different angiosperm lineages. This chapter discusses some of the traits associated with wood formation, what is currently known about the genes and mechanisms regulating these traits, and how comparative evolution- ary genomic studies can be undertaken to provide more comprehensive views of the evolution and development of wood formation in angiosperms. Keywords Wood formation • Wood development • Wood evolution • Transcriptional regulation • Epigenetics • Comparative genomics Genomic Perspectives on the Evolutionary Origins and Variation in Angiosperm Wood Introduction The evolutionary and developmental biology of wood are fundamental to under- standing the amazing diversification of angiosperms. While flower morphology and reproductive characters associated with angiosperms have been the focus of numer- ous genetic and genomic evo-devo studies, wood development is a relatively neglected trait of angiosperm evolution and development that is now tractable for comparative and evolutionary genomic studies. The ability to produce wood from a X. He School of Life Sciences, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China A.T. Groover (*) Pacific Southwest Research Station, US Forest Service, Davis, 95618 CA, USA Department of Plant Biology, University of California Davis, Davis, 95618 CA, USA e-mail: [email protected] © Springer International Publishing AG 2017 205 A.T. Groover and Q.C.B. -

Ovule and Embryo Development, Apomixis and Fertilization Abdul M Chaudhury, Stuart Craig, ES Dennis and WJ Peacock

26 Ovule and embryo development, apomixis and fertilization Abdul M Chaudhury, Stuart Craig, ES Dennis and WJ Peacock Genetic analyses, particularly in Arabidopsis, have led to Figure 1 the identi®cation of mutants that de®ne different steps of ovule ontogeny, pollen stigma interaction, pollen tube growth, and fertilization. Isolation of the genes de®ned by these Micropyle mutations promises to lead to a molecular understanding of (a) these processes. Mutants have also been obtained in which Synergid processes that are normally triggered by fertilization, such as endosperm formation and initiation of seed development, Egg cell occur without fertilization. These mutants may illuminate Polar Nuclei apomixis, a process of seed development without fertilization extant in many plants. Antipodal cells Chalazi Address Female Gametophyte CSIRO Plant Industry, GPO BOX 1600, ACT 2601, Australia; e-mail:[email protected] (b) (c) Current Opinion in Plant Biology 1998, 1:26±31 Pollen tube Funiculus http://biomednet.com/elecref/1369526600100026 Integument Zygote Fusion of Current Biology Ltd ISSN 1369-5266 egg and Primary sperm nuclei Endosperm Abbreviations cell ®s fertilization-independent seed Fused Polar ®e fertilization-independent endosperm Nuclei and Sperm Double Fertilization Introduction Ovules are critical in plant sexual reproduction. They (d) (e) contain a nucellus (the site of megasporogenesis), one or two integuments that develop into the seed coat and Globular a funiculus that connects the ovule to the ovary wall. embryo Embryo The nucellar megasporangium produces meiotic cells, one of which subsequently undergoes megagametogenesis to Endosperm produce the mature female gametophyte containing eight haploid nuclei [1] (Figure 1). One of these eight nuclei becomes the egg. -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

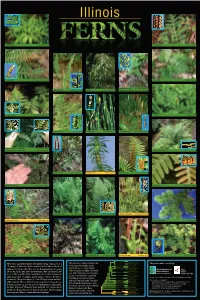

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants. -

Plant Evolution and Diversity B. Importance of Plants C. Where Do Plants Fit, Evolutionarily? What Are the Defining Traits of Pl

Plant Evolution and Diversity Reading: Chap. 30 A. Plants: fundamentals I. What is a plant? What does it do? A. Basic structure and function B. Why are plants important? - Photosynthesize C. What are plants, evolutionarily? -CO2 uptake D. Problems of living on land -O2 release II. Overview of major plant taxa - Water loss A. Bryophytes (seedless, nonvascular) - Water and nutrient uptake B. Pterophytes (seedless, vascular) C. Gymnosperms (seeds, vascular) -Grow D. Angiosperms (seeds, vascular, and flowers+fruits) Where? Which directions? II. Major evolutionary trends - Reproduce A. Vascular tissue, leaves, & roots B. Fertilization without water: pollen C. Dispersal: from spores to bare seeds to seeds in fruits D. Life cycles Æ reduction of gametophyte, dominance of sporophyte Fig. 1.10, Raven et al. B. Importance of plants C. Where do plants fit, evolutionarily? 1. Food – agriculture, ecosystems 2. Habitat 3. Fuel and fiber 4. Medicines 5. Ecosystem services How are protists related to higher plants? Algae are eukaryotic photosynthetic organisms that are not plants. Relationship to the protists What are the defining traits of plants? - Multicellular, eukaryotic, photosynthetic autotrophs - Cell chemistry: - Chlorophyll a and b - Cell walls of cellulose (plus other polymers) - Starch as a storage polymer - Most similar to some Chlorophyta: Charophyceans Fig. 29.8 Points 1. Photosynthetic protists are spread throughout many groups. 2. Plants are most closely related to the green algae, in particular, to the Charophyceans. Coleochaete 3. -

Dicot/Monocot Root Anatomy the Figure Shown Below Is a Cross Section of the Herbaceous Dicot Root Ranunculus. the Vascular Tissu

Dicot/Monocot Root Anatomy The figure shown below is a cross section of the herbaceous dicot root Ranunculus. The vascular tissue is in the very center of the root. The ground tissue surrounding the vascular cylinder is the cortex. An epidermis surrounds the entire root. The central region of vascular tissue is termed the vascular cylinder. Note that the innermost layer of the cortex is stained red. This layer is the endodermis. The endodermis was derived from the ground meristem and is properly part of the cortex. All the tissues inside the endodermis were derived from procambium. Xylem fills the very middle of the vascular cylinder and its boundary is marked by ridges and valleys. The valleys are filled with phloem, and there are as many strands of phloem as there are ridges of the xylem. Note that each phloem strand has one enormous sieve tube member. Outside of this cylinder of xylem and phloem, located immediately below the endodermis, is a region of cells called the pericycle. These cells give rise to lateral roots and are also important in secondary growth. Label the tissue layers in the following figure of the cross section of a mature Ranunculus root below. 1 The figure shown below is that of the monocot Zea mays (corn). Note the differences between this and the dicot root shown above. 2 Note the sclerenchymized endodermis and epidermis. In some monocot roots the hypodermis (exodermis) is also heavily sclerenchymized. There are numerous xylem points rather than the 3-5 (occasionally up to 7) generally found in the dicot root. -

Anatomical Traits Related to Stress in High Density Populations of Typha Angustifolia L

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.09715 Original Article Anatomical traits related to stress in high density populations of Typha angustifolia L. (Typhaceae) F. F. Corrêaa*, M. P. Pereiraa, R. H. Madailb, B. R. Santosc, S. Barbosac, E. M. Castroa and F. J. Pereiraa aPrograma de Pós-graduação em Botânica Aplicada, Departamento de Biologia, Universidade Federal de Lavras – UFLA, Campus Universitário, CEP 37200-000, Lavras, MG, Brazil bInstituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Sul de Minas Gerais – IFSULDEMINAS, Campus Poços de Caldas, Avenida Dirce Pereira Rosa, 300, CEP 37713-100, Poços de Caldas, MG, Brazil cInstituto de Ciências da Natureza, Universidade Federal de Alfenas – UNIFAL, Rua Gabriel Monteiro da Silva, 700, CEP 37130-000, Alfenas, MG, Brazil *e-mail: [email protected] Received: June 26, 2015 – Accepted: November 9, 2015 – Distributed: February 28, 2017 (With 3 figures) Abstract Some macrophytes species show a high growth potential, colonizing large areas on aquatic environments. Cattail (Typha angustifolia L.) uncontrolled growth causes several problems to human activities and local biodiversity, but this also may lead to competition and further problems for this species itself. Thus, the objective of this study was to investigate anatomical modifications on T. angustifolia plants from different population densities, once it can help to understand its biology. Roots and leaves were collected from natural populations growing under high and low densities. These plant materials were fixed and submitted to usual plant microtechnique procedures. Slides were observed and photographed under light microscopy and images were analyzed in the UTHSCSA-Imagetool software. The experimental design was completely randomized with two treatments and ten replicates, data were submitted to one-way ANOVA and Scott-Knott test at p<0.05. -

Basic Plant and Flower Parts

Basic Plant and Flower Parts Basic Parts of a Plant: Bud - the undeveloped flower of a plant Flower - the reproductive structure in flowering plants where seeds are produced Fruit - the ripened ovary of a plant that contains the seeds; becomes fleshy or hard and dry after fertilization to protect the developing seeds Leaf - the light absorbing structure and food making factory of plants; site of photosynthesis Root - anchors the plant and absorbs water and nutrients from the soil Seed - the ripened ovule of a plant, containing the plant embryo, endosperm (stored food), and a protective seed coat Stem - the support structure for the flowers and leaves; includes a vascular system (xylem and phloem) for the transport of water and food Vein - vascular structure in the leaf Basic Parts of a Flower: Anther - the pollen-bearing portion of a stamen Filament - the stalk of a stamen Ovary - the structure that encloses the undeveloped seeds of a plant Ovules - female reproductive cells of a plant Petal - one of the innermost modified leaves surrounding the reproductive organs of a plant; usually brightly colored Pistil - the female part of the flower, composed of the ovary, stigma, and style Pollen - the male reproductive cells of plants Sepal - one of the outermost modified leaves surrounding the reproductive organs of a plant; usually green Stigma - the tip of the female organ in plants, where the pollen lands Style - the stalk, or middle part, of the female organ in plants (connecting the stigma and ovary) Stamen - the male part of the flower, composed of the anther and filament; the anther produces pollen Pistil Stigma Stamen Style Anther Pollen Filament Petal Ovule Sepal Ovary Flower Vein Bud Stem Seed Fruit Leaf Root . -

Eudicots Monocots Stems Embryos Roots Leaf Venation Pollen Flowers

Monocots Eudicots Embryos One cotyledon Two cotyledons Leaf venation Veins Veins usually parallel usually netlike Stems Vascular tissue Vascular tissue scattered usually arranged in ring Roots Root system usually Taproot (main root) fibrous (no main root) usually present Pollen Pollen grain with Pollen grain with one opening three openings Flowers Floral organs usually Floral organs usually in in multiples of three multiples of four or five © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 1 Reproductive shoot (flower) Apical bud Node Internode Apical bud Shoot Vegetative shoot system Blade Leaf Petiole Axillary bud Stem Taproot Lateral Root (branch) system roots © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 2 © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 3 Storage roots Pneumatophores “Strangling” aerial roots © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 4 Stolon Rhizome Root Rhizomes Stolons Tubers © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 5 Spines Tendrils Storage leaves Stem Reproductive leaves Storage leaves © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 6 Dermal tissue Ground tissue Vascular tissue © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 7 Parenchyma cells with chloroplasts (in Elodea leaf) 60 µm (LM) © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 8 Collenchyma cells (in Helianthus stem) (LM) 5 µm © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 9 5 µm Sclereid cells (in pear) (LM) 25 µm Cell wall Fiber cells (cross section from ash tree) (LM) © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 10 Vessel Tracheids 100 µm Pits Tracheids and vessels (colorized SEM) Perforation plate Vessel element Vessel elements, with perforated end walls Tracheids © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 11 Sieve-tube elements: 3 µm longitudinal view (LM) Sieve plate Sieve-tube element (left) and companion cell: Companion cross section (TEM) cells Sieve-tube elements Plasmodesma Sieve plate 30 µm Nucleus of companion cell 15 µm Sieve-tube elements: longitudinal view Sieve plate with pores (LM) © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. -

EXTENSION EC1257 Garden Terms: Reproductive Plant Morphology — Black/PMS 186 Seeds, Flowers, and Fruitsextension

4 color EXTENSION EC1257 Garden Terms: Reproductive Plant Morphology — Black/PMS 186 Seeds, Flowers, and FruitsEXTENSION Anne Streich, Horticulture Educator Seeds Seed Formation Seeds are a plant reproductive structure, containing a Pollination is the transfer of pollen from an anther to a fertilized embryo in an arrestedBlack state of development, stigma. This may occur by wind or by pollinators. surrounded by a hard outer covering. They vary greatly Cross pollinated plants are fertilized with pollen in color, shape, size, and texture (Figure 1). Seeds are EXTENSION from other plants. dispersed by a variety of methods including animals, wind, and natural characteristics (puffball of dandelion, Self-pollinated plants are fertilized with pollen wings of maples, etc.). from their own fl owers. Fertilization is the union of the (male) sperm nucleus from the pollen grain and the (female) egg nucleus found in the ovary. If fertilization is successful, the ovule will develop into a seed and the ovary will develop into a fruit. Seed Characteristics Seed coats are the hard outer covering of seeds. They protect seed from diseases, insects and unfavorable environmental conditions. Water must be allowed through the seed coat for germination to occur. Endosperm is a food storage tissue found in seeds. It can be made up of proteins, carbohydrates, or fats. Embryos are immature plants in an arrested state of development. They will begin growth when Figure 1. A seed is a small embryonic plant enclosed in a environmental conditions are favorable. covering called the seed coat. Seeds vary in color, shape, size, and texture. Germination is the process in which seeds begin to grow. -

Secreted Molecules and Their Role in Embryo Formation in Plants : a Min-Review

Secreted molecules and their role in embryo formation in plants : a min-review. Elisabeth Matthys-Rochon To cite this version: Elisabeth Matthys-Rochon. Secreted molecules and their role in embryo formation in plants : a min- review.. acta Biologica Cracoviensia, 2005, pp.23-29. hal-00188834 HAL Id: hal-00188834 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00188834 Submitted on 31 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright ACTA BIOLOGICA CRACOVIENSIA Series Botanica 47/1: 23–29, 2005 SECRETED MOLECULES AND THEIR ROLE IN EMBRYO FORMATION IN PLANTS: A MINI-REVIEW ELISABETH MATTHYS-ROCHON* Reproduction et développement des plantes (RDP), UMR 5667 CNRS/INRA/ENS/LYON1, 46 Allée d’Italie, 69364 Lyon Cedex 07, France Received January 15, 2005; revision accepted April 2, 2005 This short review emphasizes the importance of secreted molecules (peptides, proteins, arabinogalactan proteins, PR proteins, oligosaccharides) produced by cells and multicellular structures in culture media. Several of these molecules have also been identified in planta within the micro-environment in which the embryo and endosperm develop. Questions are raised about the parallel between in vitro systems (somatic and androgenetic) and in planta zygotic development.