Values of Arctic Protected Areas: a Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

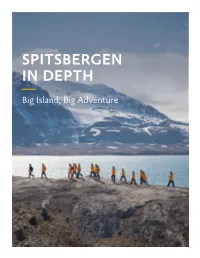

Spitsbergen in Depth

SPITSBERGEN IN DEPTH Big Island, Big Adventure Contents 1 Overview 2 Itinerary 4 Arrival and Departure Details 6 Your Ship 8 Included Activities 9 Adventure Options 10 Dates & Rates 11 Inclusions & Exclusions 13 Your Expedition Team 13 Extend Your Trip 14 Meals on Board 15 Possible Excursions 18 Packing Checklist Overview Spitsbergen in Depth: Big Island, Big Adventure This 14-day journey offers the most extensive exploration of Spitsbergen in the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard, including the opportunity to witness iconic Arctic wildlife like walrus, reindeer and polar bears, a glimpse into 16th-century EXPEDITION IN BRIEF maritime culture at secluded landing sites, and the rare chance to appreciate breathtaking views at the birdwatching utopias 14th of July Glacier and Alkefjellet. Encounter iconic Arctic wildlife, such as polar bears, walrus and reindeer If conditions allow, we will also attempt a full circumnavigation of the Arctic during this memorable voyage, including a visit to the remote, uninhabited Arctic desert View numerous Arctic bird species, like puffins, Arctic terns and purple of Nordaustlandet. sandpipers The wildlife-viewing opportunities on this trip will leave you with plenty of Take advantage of continuous daylight memories—and photos: the walrus with its long tusks and distinctive whiskers; Explore glaciers, fjords, icebergs and Arctic birds in the thousands—in all their varied majesty; small herds of reindeer more with included Zodiac cruising loping across the tundra; and that most iconic of Arctic creatures, the polar bear, Immerse yourself in the icy realm especially as it prowls the edges of the pack ice on the perpetual hunt for food. -

Our Arctic Nation a U.S

Connecting the United States to the Arctic OUR ARCTIC NATION A U.S. Arctic Council Chairmanship Initiative Cover Photo: Cover Photo: Hosting Arctic Council meetings during the U.S. Chairmanship gave the United States an opportunity to share the beauty of America’s Arctic state, Alaska—including this glacier ice cave near Juneau—with thousands of international visitors. Photo: David Lienemann, www. davidlienemann.com OUR ARCTIC NATION Connecting the United States to the Arctic A U.S. Arctic Council Chairmanship Initiative TABLE OF CONTENTS 01 Alabama . .2 14 Illinois . 32 02 Alaska . .4 15 Indiana . 34 03 Arizona. 10 16 Iowa . 36 04 Arkansas . 12 17 Kansas . 38 05 California. 14 18 Kentucky . 40 06 Colorado . 16 19 Louisiana. 42 07 Connecticut. 18 20 Maine . 44 08 Delaware . 20 21 Maryland. 46 09 District of Columbia . 22 22 Massachusetts . 48 10 Florida . 24 23 Michigan . 50 11 Georgia. 26 24 Minnesota . 52 12 Hawai‘i. 28 25 Mississippi . 54 Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska. Photo: iStock.com 13 Idaho . 30 26 Missouri . 56 27 Montana . 58 40 Rhode Island . 84 28 Nebraska . 60 41 South Carolina . 86 29 Nevada. 62 42 South Dakota . 88 30 New Hampshire . 64 43 Tennessee . 90 31 New Jersey . 66 44 Texas. 92 32 New Mexico . 68 45 Utah . 94 33 New York . 70 46 Vermont . 96 34 North Carolina . 72 47 Virginia . 98 35 North Dakota . 74 48 Washington. .100 36 Ohio . 76 49 West Virginia . .102 37 Oklahoma . 78 50 Wisconsin . .104 38 Oregon. 80 51 Wyoming. .106 39 Pennsylvania . 82 WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE AN ARCTIC NATION? oday, the Arctic region commands the world’s attention as never before. -

Russia and the Eurasian Republics THIS REGION Spans the Continents of Europe and Asia

390-391 U5 CH14 UO TWIP-860976 3/15/04 5:21 AM Page 390 Unit Workers on the statue Russians in front of Motherland Calls, St. Basil’s Cathedral, Volgograd Moscow 224 390-391 U5 CH14 UO TWIP-860976 3/15/04 5:22 AM Page 391 RussiaRussia andand the the EurasianEurasian f you had to describe Russia RepublicsRepublics Iin one word, that word would be BIG! Russia is the largest country in the world in area. Its almost 6.6 million square miles (17 million sq. km) are spread across two continents—Europe and Asia. As you can imagine, such a large country faces equally large challenges. In 1991 Russia emerged from the Soviet Union as an independent country. Since then it has been struggling to unite its many ethnic groups, set up a demo- cratic government, and build a stable economy. ▼ Siberian tiger in a forest NGS ONLINE in eastern Russia www.nationalgeographic.com/education 225 392-401 U5 CH14 RA TWIP-860976 3/15/04 5:28 AM Page 392 REGIONAL ATLAS Focus on: Russia and the Eurasian Republics THIS REGION spans the continents of Europe and Asia. It includes Russia—the world’s largest country—and the neigh- boring independent republics of Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. Russia and the Eurasian republics cover about 8 million square miles (20.7 million sq. km). This is greater than the size of Canada, the United States, and Mexico combined. The Caspian Sea is actually a salt lake that lies at the base of the Caucasus Mountains in The Land Russia’s southwest. -

Gap Analysis in Support of Cpan: the Russian Arctic

CAFF Habitat Conservation Report No. 9 GAP ANALYSIS IN SUPPORT OF CPAN: THE RUSSIAN ARCTIC Igor Lysenko and David Henry CAFF INTERNATIONAL SECRETRARIAT 2000 This report, prepared by Igor Lysenko, World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) and David Henry, United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) Global Resource Information Database (GRID)-Arendal, is a technical account of a Gap Analysis Project conducted for the Russian Arctic in 1997-1999 in support of the Circumpolar Protected Areas Network (CPAN) of CAFF. It updates the status and spatial distribution of protected areas within the CAFF area of the Russian Federation and provides, in 22 GIs based maps and several data sets, a wealth of information relevant for present and future management decisions related to habitat conservation in the Russian Arctic. The present Gap Analysis for the Russian Arctic was undertaken in response to the CPAN Strategy and Action Plan requirement for countries to identify gaps in protected area coverage of ecosystems and species and to select sites for further action. Another important objective was to update the Russian data base. The Analysis used a system of twelve landscape units instead of the previously used vegetation zone system as the basis to classify Russia's ecosystems. A comparison of the terrestrial landscape systems against protected area coverage indicates that 27% of the glacier ecosystem is protected, 9.3% of the tundra (treeless portion) and 4.7% of the forest systems within the Arctic boundaries are under protection, but the most important Arctic forested areas have only 0.1% protection. In general, the analysis indicates a negative relationship between ecosystem productivity and protection, which is consistent with findings in 1996. -

Distribution of Freshwater Midges in Relation to Air Temperature and Lake Depth

J Paleolimnol (2006) 36:295-314 DOl 1O.1007/s10933-006-0014-6 A northwest North American training set: distribution of freshwater midges in relation to air temperature and lake depth Erin M. Barley' Ian R. Walker' Joshua Kurek, Les C. Cwynar' Rolf W. Mathewes • Konrad Gajewski' Bruce P. Finney Received: 20 July 2005 I Accepted: 5 March 2006/Published online: 26 August 2006 © Springer Science+Business Media B.Y. 2006 Abstract Freshwater midges, consisting of Chiro- organic carbon, lichen woodland vegetation and sur- nomidae, Chaoboridae and Ceratopogonidae, were face area contributed significantly to explaining assessed as a biological proxy for palaeoclimate in midge distribution. Weighted averaging partial least eastern Beringia. The northwest North American squares (WA-PLS) was used to develop midge training set consists of midge assemblages and data inference models for mean July air temperature 2 for 17 environmental variables collected from 145 (R boot = 0.818, RMSEP = 1.46°C), and transformed 2 lakes in Alaska, British Columbia, Yukon, Northwest depth (1n (x+ l); R boot = 0.38, and RMSEP = 0.58). Territories, and the Canadian Arctic Islands. Canon- ical correspondence analyses (CCA) revealed that Key words Chironomidae : Transfer function . mean July air temperature, lake depth, arctic tundra Beringia' Air temperature . Lake depth' Canonical vegetation, alpine tundra vegetation, pH, dissolved correspondence analysis . Paleoclimate E. M. Barley· R. W. Mathewes Department of Biological Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada V5A IS6 Introduction I. R. Walker Departments of Biology, and Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of British Columbia Okanagan, Palaeoecologists seeking to quantify past environ- Kelowna, BC, Canada VIV IV7 mental changes rely increasingly on transfer func- e-mail: [email protected] tions that make use of biological proxies (Battarbee J. -

Siberia and the Russian Far East in the 21St Century: Scenarios of the Future

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 11 (2017 10) 1669-1686 ~ ~ ~ УДК 332.1:338.1(571) Siberia and the Russian Far East in the 21st Century: Scenarios of the Future Valerii S. Efimov and Alla V. Laptevа* Siberian Federal University 79 Svobodny, Krasnoyarsk, 660041, Russia Received 07.09.2017, received in revised form 07.11.2017, accepted 14.11.2017 The article presents a study of variants of possible future for Siberia and Russian Far East up until 2050. The authors consider the global trends that are likely to determine the situation of Russia and the Siberian macro-region in the long term. It is shown that the demand for natural resources of Siberia and Russian Far East will be determined by the economic development of Asian countries, the processes of urbanization and the growth of urban “middle class”. When determining possible scenarios, the authors use a method of conceptual scenario planning that was developed under the framework of foresight technology. Three groups of scenario factors became the basis for determining scenarios: external constant conditions, external variable factors, internal variable factors. Combinations of scenario factors set the field for the possible variants of the future of Siberia and Russian East. The article describes four key scenarios: “Broad international cooperation”, “Exclusive partnership”, “Optimization of the country”, “Retention of territory”. For each of them the authors provide “the image of the future” (including the main features of international cooperation, economic and social development), as well as the quantitative estimation of population and GDP dynamics: • “Broad international cooperation” – the population of Russia will increase by 15.7 % from 146.5 million in 2015 to 169.5 million in 2050; Russia’s GDP will grow by 3.4 times – from 3.8 trillion dollars (PPP) in 2015 to 12.8 trillion dollars in 2050. -

Consensus Statement

Arctic Climate Forum Consensus Statement 2020-2021 Arctic Winter Seasonal Climate Outlook (along with a summary of 2020 Arctic Summer Season) CONTEXT Arctic temperatures continue to warm at more than twice the global mean. Annual surface air temperatures over the last 5 years (2016–2020) in the Arctic (60°–85°N) have been the highest in the time series of observations for 1936-20201. Though the extent of winter sea-ice approached the median of the last 40 years, both the extent and the volume of Arctic sea-ice present in September 2020 were the second lowest since 1979 (with 2012 holding minimum records)2. To support Arctic decision makers in this changing climate, the recently established Arctic Climate Forum (ACF) convened by the Arctic Regional Climate Centre Network (ArcRCC-Network) under the auspices of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) provides consensus climate outlook statements in May prior to summer thawing and sea-ice break-up, and in October before the winter freezing and the return of sea-ice. The role of the ArcRCC-Network is to foster collaborative regional climate services amongst Arctic meteorological and ice services to synthesize observations, historical trends, forecast models and fill gaps with regional expertise to produce consensus climate statements. These statements include a review of the major climate features of the previous season, and outlooks for the upcoming season for temperature, precipitation and sea-ice. The elements of the consensus statements are presented and discussed at the Arctic Climate Forum (ACF) sessions with both providers and users of climate information in the Arctic twice a year in May and October, the later typically held online. -

Recent Declines in Warming and Vegetation Greening Trends Over Pan-Arctic Tundra

Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 4229-4254; doi:10.3390/rs5094229 OPEN ACCESS Remote Sensing ISSN 2072-4292 www.mdpi.com/journal/remotesensing Article Recent Declines in Warming and Vegetation Greening Trends over Pan-Arctic Tundra Uma S. Bhatt 1,*, Donald A. Walker 2, Martha K. Raynolds 2, Peter A. Bieniek 1,3, Howard E. Epstein 4, Josefino C. Comiso 5, Jorge E. Pinzon 6, Compton J. Tucker 6 and Igor V. Polyakov 3 1 Geophysical Institute, Department of Atmospheric Sciences, College of Natural Science and Mathematics, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 903 Koyukuk Dr., Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Institute of Arctic Biology, Department of Biology and Wildlife, College of Natural Science and Mathematics, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, P.O. Box 757000, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (D.A.W.); [email protected] (M.K.R.) 3 International Arctic Research Center, Department of Atmospheric Sciences, College of Natural Science and Mathematics, 930 Koyukuk Dr., Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Virginia, 291 McCormick Rd., Charlottesville, VA 22904, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 5 Cryospheric Sciences Branch, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Code 614.1, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 6 Biospheric Science Branch, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Code 614.1, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (J.E.P.); [email protected] (C.J.T.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-907-474-2662; Fax: +1-907-474-2473. -

February 17, 2016

The Arctic in 2045: A Long Term Vision Okalik Eegeesiak | Wilton Park, London, UK| February 17, 2016 An Inuit Vision of the Arctic in 2045 (check against delivery) Ullukkut, Good afternoon. My name is Okalik Eegeesiak. First, thank you to the organizers for the invitation to speak at this conference at such a beautiful and inspiring venue and to the participants who share the value of the Arctic and its peoples. A thirty year vision for the Arctic is important. Inuit believe in a vision for the Arctic – our vision looks back and forward – guided by our past to inform our future. I hope my thoughts will add to the discussion. I will share with you about what Inuit are doing to secure our vision and how we can work together for our shared vision of the Arctic. Inuit have occupied the circumpolar Arctic for millennia – carving a resilient and pragmatic culture from the land and sea – we have lived through famines, the little ice age, Vikings, whalers, missionaries, residential schools, successive governments and we intend to thrive with climate change. A documentary was recently released in Canada that told of the accounts of two Inuit families and an single man from Labrador, Canada now called Nunatsiavut – these Inuit were brought to Europe in the 1880’s and displayed in “zoo’s”. Their remains are still in storage in museums in France and Germany and their predecessors are now working to repatriate them. I share these struggles and trauma to illustrate that we have come a long way… and I am with a solid foundation of our history. -

Control of the Value of Black Goldminers' Labour-Power in South

Farouk Stemmet Control of the Value of Black Goldminers’ Labour-Power in South Africa in the Early Industrial Period as a Consequence of the Disjuncture between the Rising Value of Gold and its ‘Fixed Price’ Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Glasgow October, 1993. © Farouk Stemmet, MCMXCIII ProQuest Number: 13818401 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818401 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 GLASGOW UNIVFRSIT7 LIBRARY Abstract The title of this thesis,Control of the Value of Black Goldminers' Labour- Power in South Africa in the Early Industrial Period as a Consequence of the Disjuncture between the Rising Value of Gold and'Fixed its Price', presents, in reverse, the sequence of arguments that make up this dissertation. The revolution which took place in the value of gold, the measure of value, in the second half of the nineteenth century, coincided with the need of international trade to hold fast the value-ratio at which the world's various paper currencies represented a definite weight of gold. -

Sediment Transport to the Laptev Sea-Hydrology and Geochemistry of the Lena River

Sediment transport to the Laptev Sea-hydrology and geochemistry of the Lena River V. RACHOLD, A. ALABYAN, H.-W. HUBBERTEN, V. N. KOROTAEV and A. A, ZAITSEV Rachold, V., Alabyan, A., Hubberten, H.-W., Korotaev, V. N. & Zaitsev, A. A. 1996: Sediment transport to the Laptev Sea-hydrology and geochemistry of the Lena River. Polar Research 15(2), 183-196. This study focuses on the fluvial sediment input to the Laptev Sea and concentrates on the hydrology of the Lena basin and the geochemistry of the suspended particulate material. The paper presents data on annual water discharge, sediment transport and seasonal variations of sediment transport. The data are based on daily measurements of hydrometeorological stations and additional analyses of the SPM concentrations carried out during expeditions from 1975 to 1981. Samples of the SPM collected during an expedition in 1994 were analysed for major, trace, and rare earth elements by ICP-OES and ICP-MS. Approximately 700 h3freshwater and 27 x lo6 tons of sediment per year are supplied to the Laptev Sea by Siberian rivers, mainly by the Lena River. Due to the climatic situation of the drainage area, almost the entire material is transported between June and September. However, only a minor part of the sediments transported by the Lena River enters the Laptev Sea shelf through the main channels of the delta, while the rest is dispersed within the network of the Lena Delta. Because the Lena River drains a large basin of 2.5 x lo6 km2,the chemical composition of the SPM shows a very uniform composition. -

Arctic Species Trend Index 2010

Arctic Species Trend Index 2010Tracking Trends in Arctic Wildlife CAFF CBMP Report No. 20 discover the arctic species trend index: www.asti.is ARCTIC COUNCIL Acknowledgements CAFF Designated Agencies: • Directorate for Nature Management, Trondheim, Norway • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland • Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Reykjavik, Iceland • The Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment, the Environmental Agency, the Government of Greenland • Russian Federation Ministry of Natural Resources, Moscow, Russia • Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Stockholm, Sweden • United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska CAFF Permanent Participant Organisations: • Aleut International Association (AIA) • Arctic Athabaskan Council (AAC) • Gwich’in Council International (GCI) • Inuit Circumpolar Conference (ICC) Greenland, Alaska and Canada • Russian Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) • The Saami Council This publication should be cited as: Louise McRae, Christoph Zöckler, Michael Gill, Jonathan Loh, Julia Latham, Nicola Harrison, Jenny Martin and Ben Collen. 2010. Arctic Species Trend Index 2010: Tracking Trends in Arctic Wildlife. CAFF CBMP Report No. 20, CAFF International Secretariat, Akureyri, Iceland. For more information please contact: CAFF International Secretariat Borgir, Nordurslod 600 Akureyri, Iceland Phone: +354 462-3350 Fax: +354 462-3390 Email: [email protected] Website: www.caff.is Design & Layout: Lily Gontard Cover photo courtesy of Joelle Taillon. March 2010 ___ CAFF Designated Area Report Authors: Louise McRae, Christoph Zöckler, Michael Gill, Jonathan Loh, Julia Latham, Nicola Harrison, Jenny Martin and Ben Collen This report was commissioned by the Circumpolar Biodiversity Monitoring Program (CBMP) with funding provided by the Government of Canada.