Quartetto Di Cremona Ludwig Van Beethoven String Quartet in F Major, Op

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Chronology of All Artists' Appearances with the Chamber

75 Years of Chamber Music Excellence: A Chronology of all artists’ appearances with the Chamber Music Society of Louisville st 1 Season, 1938 – 1939 Kathleen Parlow, violin and Gunnar Johansen, piano The Gordon String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Heermann Trio nd 2 Season, 1939 – 1940 The Budapest String Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet Marcel Hubert, cello and Harold Dart, piano rd 3 Season, 1940 – 1941 Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord and Lois Wann, oboe Belgian PianoString Quartet The Coolidge Quartet th 4 Season, 1941 – 1942 The Trio of New York The Musical Art Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet th 5 Season, 1942 – 1943 The Budapest String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet th 6 Season, 1943 – 1944 The Budapest String Quartet Gunnar Johansen, piano and Antonio Brosa, violin The Musical Art Quartet th 7 Season, 1944 – 1945 The Budapest String Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord th 8 Season, 1945 – 1946 The Musical Art Quartet Nikolai Graudan, cello and Joanna Graudan, piano Philip Manuel, harpsichord and Gavin Williamson, harpsichord The Budpest String Quartet th 9 Season, 1946 – 1947 The Louisville Philharmonic String Quartet with Doris Davis, piano The Albeneri Trio The Budapest String Quartet th 10 Season, 1947 – 1948 Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord The Budapest String Quartet The London String Quartet The Walden String Quartet The Albeneri Trio th 11 Season, 1948 – 1949 The Alma Trio -

The Juilliard Journal

FACULTY PORTRAIT Paul Neubauer Viola Faculty March 2017 After graduating from Juilliard, Paul Neubauer (BM '82, MM '83) became, at age 21, the youngest string principal ever to join the New York Philharmonic, where he spent six years before leaving in 1990 to pursue solo and chamber work. Along the way he joined the Juilliard faculty and the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, in 1989. Appointed last spring as artistic director of the Mostly Music series in New Jersey, he'll make his Chicago Symphony debut in 2018. Why did you become a violist? It truly was my destiny. My godfather was the Viennese-born violist Paul Doktor (faculty 1971–89), and he was a major influence in my musical and personal evolution from a very early age. I also studied with him during my teenage summers and at Juilliard. On top of this, my older siblings played the violin and cello, so viola was the perfect choice since this would complete a string trio. Unfortunately that string trio lasted about 10 minutes since my siblings were not as committed to a life in classical music. And you're still part of a musical family … Yes, my wife, Kerry McDermott, is a violinist with the New York Philharmonic, and our children, Oliver and Clara, both play the violin and attend the Juilliard Pre-College program. I have told my children countless times that the viola is a superior instrument to the violin, but they unfortunately have not taken my advice as of yet. On occasion, we enjoy playing four-violin quartets with three violins and a viola. -

Rehearing Beethoven Festival Program, Complete, November-December 2020

CONCERTS FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 2020-2021 Friends of Music The Da Capo Fund in the Library of Congress The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress (RE)HEARING BEETHOVEN FESTIVAL November 20 - December 17, 2020 The Library of Congress Virtual Events We are grateful to the thoughtful FRIENDS OF MUSIC donors who have made the (Re)Hearing Beethoven festival possible. Our warm thanks go to Allan Reiter and to two anonymous benefactors for their generous gifts supporting this project. The DA CAPO FUND, established by an anonymous donor in 1978, supports concerts, lectures, publications, seminars and other activities which enrich scholarly research in music using items from the collections of the Music Division. The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress was created in 1992 by William Remsen Strickland, noted American conductor, for the promotion and advancement of American music through lectures, publications, commissions, concerts of chamber music, radio broadcasts, and recordings, Mr. Strickland taught at the Juilliard School of Music and served as music director of the Oratorio Society of New York, which he conducted at the inaugural concert to raise funds for saving Carnegie Hall. A friend of Mr. Strickland and a piano teacher, Ms. Hull studied at the Peabody Conservatory and was best known for her duets with Mary Howe. Interviews, Curator Talks, Lectures and More Resources Dig deeper into Beethoven's music by exploring our series of interviews, lectures, curator talks, finding guides and extra resources by visiting https://loc.gov/concerts/beethoven.html How to Watch Concerts from the Library of Congress Virtual Events 1) See each individual event page at loc.gov/concerts 2) Watch on the Library's YouTube channel: youtube.com/loc Some videos will only be accessible for a limited period of time. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 115, 1995-1996

BOSTON > V SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ft SEIJIOZAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR 9 6 S E O N The security of a trust, Fidelity investment expertise. A CLumlc Composition Fidelity Just as a Beethoven score is at its best when performed by a world- Pergonal class symphony — so, too, should your trust assets be managed by Triittt a financial company recognized Serviced globally for its investment expertise. Fidelity Investments. That's why Fidelity now offers a % managed trust or personalized estment management account or your portfolio of $400,000 or more/ For more information, visit Fidelity Investor Center or call Fidelity Pergonal Trust Services at 1-800-854-2829. Visit a Fidelity Investor Center Near You: Boston - Back Bay • Boston - Financial District Braintree, MA • Burlington, MA Fidelity Investments' SERVICES OFFERED ONLY THROUGH AUTHORIZED TRUST COMPANIES. TRUST SERVICES VARY BY STATE. FIDELITY BROKERAGE SERVICES, INC., MEMBER NYSE, SIPC. Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Fifteenth Season, 1995-96 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. J. P. Barger, Chairman Nicholas T. Zervas, President Peter A. Brooke, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Mrs. Edith L. Dabney, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson Nader F. Darehshori Edna S. Kalman Mrs. Robert B. Newman James F. Cleary Deborah B. Davis Allen Z. Kluchman Robert P. O'Block John E. Cogan, Jr. Nina L. Doggett George Krupp Peter C. Read Julian Cohen Avram J. Goldberg R. Willis Leith, Jr. Carol Scheifele-Holmes Chairman-elect William F. -

Quartet Dimensions

concert program ii: Quartet Dimensions JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685–1750)! July 21 WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756–1791) Sunday, July 21, 6:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts Fugue in E-flat Major, BWV 876, and Fugue in d minor, BWV 877, from at Menlo-Atherton Das wohltemperierte Klavier; arr. String Quartets nos. 7 and 8, K. 405 JOSEPH HAYDN (1732–1809) PROGRAM OVERVIEW String Quartet in d minor, op. 76, no. 2, Quinten (1796) The string quartet medium, arguably the spinal column of the Allegro chamber music literature, did not exist in Bach’s lifetime. Yet Andante o più tosto allegretto Minuetto: Allegro ma non troppo even here, Bach’s legacy is inescapable. The fugues of his semi- Finale: Vivace assai nal The Well-Tempered Clavier inspired no less a genius than Danish String Quartet: Frederik Øland, Rune Tonsgaard Sørensen, violins; Asbjørn Nørgaard, viola; Mozart, who arranged a set of them for string quartet. The influ- Fredrik Schøyen Sjölin, cello ence of Bach’s architectural mastery permeates the ingenious DMITRY SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–1975) Quinten Quartet of Joseph Haydn, the father of the modern Piano Quintet in g minor, op. 57 (1940) string quartet, and even Dmitry Shostakovich’s Piano Quintet, Prelude composed nearly two hundred years after Bach’s death. The Fugue Scherzo centerpiece of Beethoven’s Opus 132—the Heiliger Dankgesang Intermezzo CONCERT PROGRAMSCONCERT eines Genesenen an die Gottheit (“A Convalescent’s Holy Song Finale PROGRAMSCONCERT of Thanksgiving to the Divinity”)—recalls another Bachian signa- Gilbert Kalish, piano; Danish String Quartet: Frederik Øland, Rune Tonsgaard Sørensen, violins; ture: the Baroque master’s sacred chorales. -

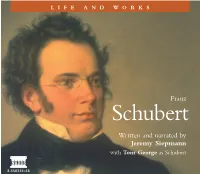

Franz Schubert Written and Narrated by Jeremy Siepmann with Tom George As Schubert

LIFE AND WORKS Franz Schubert Written and narrated by Jeremy Siepmann with Tom George as Schubert 8.558135–38 Life and Works: Franz Schubert Preface If music is ‘about’ anything, it’s about life. No other medium can so quickly or more comprehensively lay bare the very soul of those who make or compose it. Biographies confined to the limitations of text are therefore at a serious disadvantage when it comes to the lives of composers. Only by combining verbal language with the music itself can one hope to achieve a fully rounded portrait. In the present series, the words of composers and their contemporaries are brought to life by distinguished actors in a narrative liberally spiced with musical illustrations. Unlike the standard audio portrait, the music is not used here simply for purposes of illustration within a basically narrative context. Thus we often hear very substantial chunks, and in several cases whole movements, which may be felt by some to ‘interrupt’ the story; but as its title implies the series is not just about the lives of the great composers, it is also an exploration of their works. Dismemberment of these for ‘theatrical’ effect would thus be almost sacrilegious! Likewise, the booklet is more than a complementary appendage and may be read independently, with no loss of interest or connection. Jeremy Siepmann 8.558135–38 3 Life and Works: Franz Schubert © AKG Portrait of Franz Schubert, watercolour, by Wilhelm August Rieder 8.558135–38 Life and Works: Franz Schubert Franz Schubert(1797-1828) Contents Page Track Lists 6 Cast 11 1 Historical Background: The Nineteenth Century 16 2 Schubert in His Time 26 3 The Major Works and Their Significance 41 4 A Graded Listening Plan 68 5 Recommended Reading 76 6 Personalities 82 7 A Calendar of Schubert’s Life 98 8 Glossary 132 The full spoken text can be found on the CD-ROM part of the discs and at: www.naxos.com/lifeandworks/schubert/spokentext 8.558135–38 5 Life and Works: Franz Schubert 1 Piano Quintet in A major (‘Trout’), D. -

Giacomo Puccini’S Chamber Music Is Perhaps Less Familiar to the Wider Audience

BIOGRAPHY Noûs (nùs) is an ancient greek word whose meaning is mind and therefore rationality, but also inspiration CONWAY and creativity. THE QUARTETTO NOÛS, composed of four young Italian musicians, was founded in 2011 at the Conservatorio della Svizzera Italiana in Lugano. The quartet received its training at HALL the Accademia “Walter Stauffer” in Cremona in the class of the Quartetto di Cremona, at the Musik SUNDAY Akademie in Basel in the class of Professor Reiner Schmidt (Hagen Quartet) and also studied with internationally renowned Professors like Hatto Beyerle (Alban Berg Quartet) and Aldo Campagnari CONCERTS (Quartetto Prometeo). It is currently attending the Musikhochschule Lübeck in the class of Professor Heime Müller (Artemis Quartet) and the Escuela Superior de Música “Reina Sofia” in Madrid in the Günter Pichler’s class (Alban Berg Quartett). The quartet won the first prize at the “Luigi Nono” International Competition in Venaria Reale, Turin, and at the XXI “Anemos International Competition” in Rome. In Patrons 2014 it was awarded an honorable mention at the “Sony Classical Talent Scout” in Madesimo, Italy. - Stephen Hough, Laura Ponsonby AGSM, Prunella Scales CBE, Roderick Swanston, Hiro Takenouchi and Timothy West CBE It received from La Fenice Theatre in Venice the “Arthur Rubinstein - Una Vita nella Musica 2015” Artistic Director - Simon Callaghan Award for revealing itself in a few years as one of the most promising Italian chamber music group and for showing in his still brief career to be able to approach the great literature for string quartet in a mature manner, seeking a reasoned and not ephemeral interpretation in the masterpieces of the classic- romantic period and of the twentieth century, continuing at the same time a serious and not episodic research even within the language of the contemporary music. -

Quartetto Di Cremona Ludwig Van Beethoven String Quartet in C Minor, Op

BEETHOVEN COMPLETE STRING QUARTETS QUARTETTO DI CREMONA LUDWIG VAN Beethoven String Quartet in C minor, Op. 18, No. 4 24:05 1. Allegro ma non tanto 8:39 II. Andante scherzoso quasi Allegretto 7:01 III. Menuetto. Allegretto – Trio 3:37 IV. Allegro – Prestissimo 4:48 ‘Great Fugue’ in B flat major, Op. 133 15:13 Overtura. Allegro – Meno mosso e moderato – Allegro – Fuga – Meno mosso e moderato – Allegro molto e con brio – Meno mosso e moderato – Allegro molto e con brio String Quartet in F major, Op. 59, No. 1 39:13 I. Allegro 10:05 II. Allegretto vivace e sempre scherzando 8:45 III. Adagio molto e mesto 12:16 IV. Thème russe. Allegro 8:07 QUARtetto DI CREMONA Cristiano Gualco, Violine Paolo Andreoli, Violine Simone Gramaglia, Viola Giovanni Scaglione, Violoncello A quartet in C minor acquired in other genres. Only once Count Lobkowitz, one of Beethoven’s aristocratic During his first years in Vienna, Beethoven patrons, commissioned six string quartets noticeably held back from composing each from Haydn and Beethoven around string quartets and instead, apparently on the end of 1798 for the fee of 400 guil- account of studying this craft, resorted to ders, was there no turning back. Whilst copying quartets by Haydn and Mozart. Of the aged Haydn did not manage to ful- course he knew exactly that the much- fil his duty entirely, Beethoven feverishly quoted Bonn farewell by Count Wald- worked, alongside large-scale works such stein – “Sustained diligence will bring you as his First Symphony, the final version of Mozart’s spirit from Haydn’s hands” – did his Piano Concerto in C and his Septet not so much refer to the piano sonatas Op. -

Digital Booklet Porgy & Bess

71 TRACKS THE AMADEUS QUARtet ReCORDINGS VOL. I BEETHOVEN Berlin, 1950-1967 recording producer: Wolfgang Gottschalk (Op. 127) Hartung (Op. 59, 2) Hermann Reuschel (Op. 18, 2-5 / Op. 59, 1 / Op. 130-133 / Op. 135 / Op. 29) Salomon (Op. 18, 1+6 / Op. 59, 3 / Op. 95) recording engineer: Siegbert Bienert (Op. 18, 5 / Op. 130-133 / Op. 29) Peter Burkowitz (Op. 18, 6) THE Heinz Opitz (Op. 18, 2 / Op. 59, 1+2 / Op. 127 / Op. 135) Preuss (Op. 18, 1 / Op. 59, 3 / Op. 95) Alfred Steinke (Op. 18, 3+4) AMADEUS QUARtet ReCORDinGS Berlin, 1950-1967 Eine Aufnahme von RIAS Berlin (lizenziert durch Deutschlandradio) recording: P 1950 - 1967 Deutschlandradio research: Rüdiger Albrecht remastering: P 2013 Ludger Böckenhoff rights: audite claims all rights arising from copyright law and competition law in relation to research, compilation and re-mastering of the original audio tapes, VOL. I BEETHOVEN as well as the publication of this CD. Violations will be prosecuted. The historical publications at audite are based, without exception, on the original tapes from broadcasting archives. In general these are the original analogue tapes, MstASTER RELEASE which attain an astonishingly high quality, even measured by today’s standards, with their tape speed of up to 76 cm/sec. The remastering – professionally com- petent and sensitively applied – also uncovers previously hidden details of the interpretations. Thus, a sound of superior quality results. CD publications based 1 on private recordings from broadcasts cannot be compared with these. AMADEUS-QUARtett further reading: Daniel Snowman: The Amadeus Quartet. The Men and the Music, violin I Norbert Brainin Robson Books (London, 1981) violin II Siegmund Nissel Gerd Indorf: Beethovens Streichquartette, Rombach Verlag (Freiburg i. -

Catalogo Per Autori Ed Esecutori

Abel, Carl Friedrich Quartetti, archi, Op. 8, No. 5, la maggiore The Salomon Quartet The Schein String Quartet Addy, Obo Wawshishijay Kronos Quartet Adorno, Theodor Wiesengrund Zwei Stucke fur Strechquartett op. 2 Buchberger Quartett Albert, Eugene : de Quartetti, archi, Op. 7, la minore Sarastro Quartett Quartetti, archi, Op. 11, mi bemolle maggiore Sarastro Quartett Alvarez, Javier Metro Chabacano Cuarteto Latinoamericano 1 Alwyn, William Quartetti, archi, n. 3 Quartet of London Rhapsody for String Quartet Arditti string quartet Andersson, Per Polska fran Hammarsvall, Delsbo The Follinger-Hedberg Quartet The Galli Quintet The Goteborg Quartet The Halsingborg Quartet The Kjellstrom Quartet The Skane Quartet Andriessen, Hendrik Il pensiero Raphael Quartet Aperghis, Georges Triangle Carre Trio Le Cercle Apostel, Hans Erich Quartetti, archi, Op. 7 LaSalle Quartet Arenskij, Anton Stepanovic Quartetti, archi, op. 35 Paul Rosenthal, Vl Matthias Maurer, Vla Godfried Hoogeveen, Vlc Nathaniel Rosen, Vlc Arriaga y Balzola, Juan Crisostomo Jacobo Antonio : de Quartetti, archi, No. 1, re minore Voces Streichquartette Quartet sine nomine Rasoumovsky Quartet Quartetti, archi, No. 2, la maggiore Voces Streichquartette Quartet sine nomine Rasoumovsky Quartet 2 Quartetti, archi, Nr. 3, mi bemolle maggiore Voces Streichquartette Quartet sine nomine Rasoumovsky Quartet Atterberg, Kurt Quartetti, archi, Op. 11 The Garaguly Quartet Aulin, Tor Vaggvisa The Follinger-Hedberg Quartet The Galli Quintet The Goteborg Quartet The Halsingborg Quartet The Kjellstrom -

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Through Brahms the ninth season July 22–August 13, 2011 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 Through Brahms Program Overview 6 Essay: “Johannes Brahms: The Great Romantic” by Calum MacDonald 8 Encounters I–IV 11 Concert Programs I–VI 30 String Quartet Programs 37 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 50 Chamber Music Institute 52 Prelude Performances 61 Koret Young Performers Concerts 64 Café Conversations 65 Master Classes 66 Open House 67 2011 Visual Artist: John Morra 68 Listening Room 69 Music@Menlo LIVE 70 2011–2012 Winter Series 72 Artist and Faculty Biographies 85 Internship Program 86 Glossary 88 Join Music@Menlo 92 Acknowledgments 95 Ticket and Performance Information 96 Calendar Cover artwork: Mertz No. 12, 2009, by John Morra. Inside (p. 67): Paintings by John Morra. Photograph of Johannes Brahms in his studio (p. 1): © The Art Archive/Museum der Stadt Wien/ Alfredo Dagli Orti. Photograph of the grave of Johannes Brahms in the Zentralfriedhof (central cemetery), Vienna, Austria (p. 5): © Chris Stock/Lebrecht Music and Arts. Photograph of Brahms (p. 7): Courtesy of Eugene Drucker in memory of Ernest Drucker. Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 69) and Ani Kavafian (p. 75): Christian Steiner. Paul Appleby (p. 72): Ken Howard. Carey Bell (p. 73): Steve Savage. Sasha Cooke (p. 74): Nick Granito. -

Quartetto Di Cremona

QUARTETTO DI CREMONA Since its formation in 2000, the Quartetto di Cremona has established a reputation as one of the most exciting chamber ensembles on the international stage, garnered universal acclaim for its high level of interpretive artistry. The 2019/20 season includes a tour in North America and one in Holland, performances of the complete Beethoven quartets’ cycle in Italy, Albania and Taiwan, concerts in Germany, Spain, France, Switzerland and Scandinavia, as well as several recitals at the major Italian musical institutions. 2020/21 season’s highlights include concerts in Geneva, Milan, Rome, at the Wigmore Hall in London and the debut at the Carnegie Hall in New York. In 2020 the Quartetto di Cremona celebrates its first twenty years of career, an important milestone for an Italian ensemble. For the occasion, distinguished concerts and record projects will be developed over consecutive seasons: several performances of the complete Beethoven quartets’ cycle, further CDs’ releases, a tour with Bach’s “The Art of the Fugue”, new music expressly composed for the Quartet. Noteworthy previous recording projects include the prizewinning Beethoven’s string quartets cycle, completed in 2018, and a double CD dedicated to Schubert, released in Spring 2019 and featuring cellist Eckart Runge, which attracted high levels of acclaim in the international press. This latter album was recorded with the Stradivarius set of instruments named “Paganini Quartet”, on kind loan from the Nippon Music Foundation (Tokyo). Frequently invited to present masterclasses in Europe, Asia, North and South America, since 2011 they are Professors at the “Walter Stauffer Academy” in Cremona.