FCTC Shadow Report 2011 Dutch Tobacco Control: out of Control?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

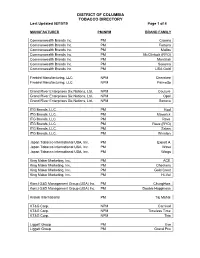

DISTRICT of COLUMBIA TOBACCO DIRECTORY Last Updated 08/15/19 Page 1 of 4

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA TOBACCO DIRECTORY Last Updated 08/15/19 Page 1 of 4 MANUFACTURER PM/NPM BRAND FAMILY Commonwealth Brands Inc. PM Crowns Commonwealth Brands Inc. PM Fortuna Commonwealth Brands Inc. PM Malibu Commonwealth Brands Inc. PM McClintock (RYO) Commonwealth Brands Inc. PM Montclair Commonwealth Brands Inc. PM Sonoma Commonwealth Brands Inc. PM USA Gold Firebird Manufacturing, LLC NPM Cherokee Firebird Manufacturing, LLC NPM Palmetto Grand River Enterprises Six Nations, Ltd. NPM Couture Grand River Enterprises Six Nations, Ltd. NPM Opal Grand River Enterprises Six Nations, Ltd. NPM Seneca ITG Brands, LLC. PM Kool ITG Brands. LLC. PM Maverick ITG Brands, LLC. PM Rave ITG Brands, LLC. PM Rave (RYO) ITG Brands, LLC. PM Salem ITG Brands, LLC. PM Winston Japan Tobacco International USA, Inc. PM Export A Japan Tobacco International USA, Inc. PM Wave Japan Tobacco International USA, Inc. PM Wings King Maker Marketing, Inc. PM ACE King Maker Marketing, Inc. PM Checkers King Maker Marketing, Inc. PM Gold Crest King Maker Marketing, Inc. PM Hi-Val Konci G&D Management Group (USA) Inc. PM ChungHwa Konci G&D Management Group (USA) Inc. PM Double Happiness Kretek International PM Taj Mahal KT&G Corp. NPM Carnival KT&G Corp. NPM Timeless Time KT&G Corp. NPM This Liggett Group PM Eve Liggett Group PM Grand Prix DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA TOBACCO DIRECTORY Last Updated 08/15/19 Page 2 of 4 MANUFACTURER PM/NPM BRAND FAMILY Liggett Group PM Liggett Select Liggett Group PM Montego Liggett Group PM Pyramid NASCO PM Red Sun NASCO PM SF Ohserase Manufacturing LLC NPM Signal Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S PM Amsterdam Shag (RYO) Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S PM Danish Export (RYO) Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S PM London Export (RYO) Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S PM Norwegian Shag (RYO) Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S PM Stockholm Blend (RYO) Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S PM Turkish Export (RYO) Philip Morris USA Inc. -

TOBACCO WORLD RETAIL PRICES (Ovor 5,000 Retail PI-ICM)

THE CIGAR AND THE TOBACCO WORLD THE POPULAR JOURNAL TOBACCO OVER 40 YEARS OF TRADE USEFULNESS WORLD The Subscription includes : TOBACCO WORLD RETAIL PRICES (Ovor 5,000 Retail PI-ICM). RETAIL PRICES THE TOBACCO WORLD ANNUAL (Containing a word of Trad* Brand*—with Nam* and Addrau In each cms*). Membership of: TOBACCO WORLD SERVICE JUNE 1935 (With Pott Fnta raplUa In all Trad* difficult!**). The Cigar & Tobacco World HIYWOOO A COMPANY LTD. Dmrr How*, Kin—U 3tr*M, Ontry Una, London, W.C1 trantfc OACM f Baadmur. •trmlnfhtn, Uteanar. ToWfTHM i OffUlfrunt, Phono, LonAon. •Phono I TomaU far M1J Published by THE CIGAR & TOBACCO WORLD HEYWOOD & CO., LTD. DRURY HOUSE, RUSSELL STREET, DRURY LANE, LONDON, W.C.2 Branch Offices: MANCHESTER, BIRMINGHAM, LEICESTER Talagrarm : "Organigram. Phono, London." Phono : Tampla Bar MZJ '' Inar) "TOBACCO WORLD" RETAIL PRICES 1935 Authorised retail prices of Tobaccos, Cigarettes, Fancy Goods, and Tobacconists' Sundries. ABDULLA & Co., Ltd. (\BDULD^ 173 New Bond Street, W.l. Telephone; Bishopsgnte 4815, Authorised Current Retail Prices. Turkish Cigarettes. Price per Box of 100 50 25 20 10 No. 5 14/6 7/4 3/8 — 1/6 No. 5 .. .. Rose Tipped .. 28/9 14/6 7/3 — 3/- No. 11 11/8 5/11 3/- - 1/3 No. II .. .. Gold Tipped .. 13/S 6/9 3/5 - No. 21 10/8 5/5 2/9 — 1/1 Turkish Coronet No. 1 7/6 3/9 1/10J 1/6 9d. No. "X" — 3/- 1/6 — — '.i^Sr*** •* "~)" "Salisbury" — 2/6 — 1/- 6d. Egyptian Cigarettes. No. 14 Special 12/5 6/3 3/2 — — No. -

B BOOM081 Binnenwerk.Indd 71 29-10-2012 14:15:56 Carla Van Baalen E.A

Carla van Baalen e.a. (red.) Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2012, pp. 71-81 www.ru.nl/cpg Goede raad is duur Het Nederlandse parlement en de Europese Raad1 Wim van Meurs De Europese Unie is niet alleen het Europa van inmiddels 500 miljoen burgers, maar ook het Europa van sinds kort (met Kroatië) 28 staten. Deze dubbele representatie doordesemt de hele Europese architectuur en de Europese besluitvormingsprocedures. Sinds de invoering van directe verkiezingen in 1979 is het Europees Parlement het meest democratische orgaan van de Unie. De Europese Raad als regelmatige ontmoeting van staatshoofden en regeringsleiders representeert daarentegen de wil van de Europese burgers slechts indirect en onttrekt zich aan het oog van de publieke opinie en aan democratische controle. Europese regeringen nemen immers in Brussel achter de gesloten deuren van de Europese Raad besluiten over reddingspakketten van honderden miljarden euro’s en ‘ombuigingen’ in de nationale begrotingen voor miljarden euro’s. In Zuid-Europa worden nationale regerin- gen gedwongen om door Brussel gedicteerde bezuinigingspakketten uit te voeren en wordt de bijbehorende wetgeving meer slecht dan recht door het parlement geloodst. Ook in het Noord-Europa van de ‘nettobetalers’ voelen de nationale parlementen en de kiezers zich door Europa in hun democratische rechten beknot. De democratische volksvertegenwoordiging in elke lidstaat staat voor een grote uitdaging: hoe kan ze in deze fase van strategische koers- bepaling haar stem laten horen en zo invloed en controle uitoefenen?2 Deze spanning tussen nationale democratie en Europese besluitvorming is het duidelijkst bij de Europese Raad, de in 1975 geïnstitutionaliseerde regelmatige ontmoeting van staatshoofden en regeringsleiders. -

North Dakota Office of State Tax Commissioner Tobacco Directory List of Participating Manufacturers (Listing by Brand) As of May 24, 2019

North Dakota Office of State Tax Commissioner Tobacco Directory List of Participating Manufacturers (Listing by Brand) As of May 24, 2019 **RYO: Roll-Your-Own Brand Name Manufacturer 1839 U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 RYO U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1st Class U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. American Bison RYO Wind River Tobacco Company, LLC Amsterdam Shag RYO Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S Ashford RYO Von Eicken Group Bali Shag RYO Commonwealth Brands, Inc. Baron American Blend Farmer’s Tobacco Co of Cynthiana, Inc. Basic Philip Morris USA, Inc. Benson & Hedges Philip Morris USA, Inc. Black & Gold Sherman’s 1400 Broadway NYC, LLC Bo Browning RYO Top Tobacco, LP Bugler RYO Scandinavian Tobacco Group Lane Limited Bull Brand RYO Von Eicken Group Cambridge Philip Morris USA, Inc. Camel R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company Camel Wides R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company Canoe RYO Wind River Tobacco Company, LLC Capri R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company Carlton R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company CF Straight Virginia RYO Von Eicken Group Charles Fairmon RYO Von Eicken Group Chesterfield Philip Morris USA, Inc. Chunghwa Konci G & D Management Group (USA) Inc. Cigarettellos Sherman’s 1400 Broadway NYC, LLC Classic Sherman’s 1400 Broadway NYC, LLC Classic Canadian RYO Top Tobacco, LP Commander Philip Morris USA, Inc. Crowns Commonwealth Brands Inc. Custom Blends RYO Wind River Tobacco Company, LLC Brand Name Manufacturer Danish Export RYO Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S Dark Fired Shag RYO Von Eicken Group Dave’s Philip Morris USA, Inc. Davidoff Commonwealth Brands, Inc. Djarum P.T. -

Medical Aspects of Tobacco Smoking and the Anti-Tobacco Movement in Britain in the Nineteenth Century

Medical History, 1980, 24: 391-402. MEDICAL ASPECTS OF TOBACCO SMOKING AND THE ANTI-TOBACCO MOVEMENT IN BRITAIN IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY by R. B. WALKER* IN THE sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries extravagant notions had been held of tobacco as the Herba Panacea, Heilkraut, and Herbe propre 'a tous maux. In the course of time these had waned and tobacco had come to be consumed more often for pleasure than for health, but about 1800 tobacco was still being used as a remedy for many ills. "Tobacco is narcotic, sedative, emetic, diuretic, cathartic, and errhine, whether it be taken into the stomach or applied externally", said James Jennings in 1830.1 Tobacco smoking was recommended as an antispasmodic for asthma and a clyster or enema of infused tobacco was employed for intestinal obstruction, strangulated hernia, and strychnine poisoning, and as a diuretic for dropsy, dysury, and ischuria. In the cholera epidemic of 1832 tobacco was injected in the vain hope of alleviating the violent purges caused by that disease.3 However, following the isolation of the nicotine content of tobacco in 1828 and the demonstration of its poisonous qualities, doctors became wary of administering so dangerous a drug. In 1863 the British Medical Journal spoke of twenty-five years' past disuse of the tobacco enema on account of its uncertain action and sometimes fatal results.4 The revision of Pereira's Materia Medica published in 1872 in expressing the same view stated that because of the widespread use of anaesthesia surgical operation for hernia was no longer dreaded.5 At Nottingham, said Dr. -

We Are a Unique Company«

INFORMATIONinside ABOUT SWEDISH MATCH FOR SHAREHOLDERS AND OTHER STAKEHOLDERS # march 2002 1 STIG-GÖRAN NILSSON Strong earnings and positive organic growth Swedish Match reports strong earnings and 8-per- cent organic growth, despite the weakening world economy. Operating income improved further dur- ing the fourth quarter, resulting in full-year increase of 16 percent. Earnings per share increased by a full 28 percent to SEK 3.54. Page 2 Success for cigars in North America Swedish Match increased both its sales volumes and its market shares for machine-made cigars in North America. The explanations for this success include a more efficient sales force and improved marketing. »This is an extremely dynamic market. You can’t afford to sit still for a single minute,« says David Price, head of marketing. Page 2–3 2001 best year ever for shareholders LENNART SUNDÉN: For Swedish Match shareholders, 2001 was the best year since the company’s stock market introduction in 1996. The share price rose 51 percent and the total return to shareholders was in excess of 53 percent, making the Swedish Match share the best- »We are a performing of the most actively traded shares on the Stockholm Exchange. The factors behind the share’s surge include the company’s strong finances, stable and positive cash flow and underlying sales growth, despite a declining economy. Page 7 unique company« Danish paradise for »We have turned the industry’s problems into an opportunity. We focus on Nordic tobacco lovers those niche areas that are growing and where profitability is high, with smoke- The Nordic region’s most prestigious tobacco store, W.Ø. -

Blunts and Blowt Jes: Cannabis Use Practices in Two Cultural Settings

Free Inquiry In Creative Sociology Volume 31 No. 1 May 2003 3 BLUNTS AND BLOWTJES: CANNABIS USE PRACTICES IN TWO CULTURAL SETTINGS AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS FOR SECONDARY PREVENTION Stephen J. Sifaneck, Institute for Special Populations Research, National Development & Research Institutes, Inc. Charles D. Kaplan, Limburg University, Maastricht, The Netherlands. Eloise Dunlap, Institute for Special Populations Research, NDRI. and Bruce D. Johnson, Institute for Special Populations Research, NDRI. ABSTRACT Thi s paper explores two modes of cannabis preparati on and smoking whic h have manifested within the dru g subcultures of th e United States and the Netherlan ds. Smoking "blunts," or hollowed out cigar wrappers fill ed wi th marijuana, is a phenomenon whi ch fi rst emerged in New York Ci ty in the mid 1980s, and has since spread throughout th e United States. A "bl owtj e," (pronounced "blowt-cha") a modern Dutch style j oint whi ch is mixed with tobacco and in cludes a card-board fi lte r and a longer rolling paper, has become th e standard mode of cannabis smoking in the Netherl ands as well as much of Europe. Both are consid ered newer than the more traditi onal practi ces of preparin g and smoking cannabis, including the traditional fi lter-less style joint, the pot pipe, an d the bong or water pipe. These newer styles of preparati on and smoking have implications for secondary preventi on efforts wi th ac tive youn g cannabis users. On a social and ritualistic level th ese practices serve as a means of self-regulating cannabi s use. -

Bezinning Op Het Buitenland

Duco Hellema, Mathieu Segers en Jan Rood (red.) Bezinning op het buitenland Het Nederlands buitenlands beleid Zijn de traditionele ijkpunten van het naoorlogse Nederlandse buitenlandse beleid in een onzekere wereld nog up to date? In hoeverre kan het bestaande buitenlandse beleid van Nederland nog gebaseerd worden op de traditionele consensus rond de drie beginselen van (1) trans-Atlantisch veiligheidsbeleid, (2) Europese economische integratie volgens de communautaire methode, en (3) ijveren voor versterking van de internationale (rechts)orde en haar multilaterale instellingen? Is er sprake van een teloorgang van die consensus en verwarring over de nieuwe werkelijkheid? Recente internationale ontwikkelingen op veiligheidspolitiek, economisch, financieel, monetair en institutioneel terrein, als mede op het gebied van mensenrechten en Duco Hellema, Mathieu Segers en Jan Rood (red.) ontwikkelingssamenwerking, dagen uit tot een herbezinning op de kernwaarden en uitgangspunten van het Nederlandse buitenlandse beleid. Het lijkt daarbij urgent een dergelijke herbezinning nu eens niet louter ‘van buiten naar binnen’, maar ook andersom vorm te geven. Het gaat derhalve niet alleen om de vraag wat de veranderingen in de wereld voor gevolgen (moeten) hebben voor het Nederlandse buitenlands beleid. Ook dient nagegaan te worden in hoeverre de Nederlandse perceptie van de eigen rol in de internationale politiek (nog) adequaat is. In verlengde hiervan zijn meer historische vragen te stellen. In hoeverre is daadwerkelijk sprake van constanten in het -

Anthropology of Tobacco

Anthropology of Tobacco Tobacco has become one of the most widely used and traded commodities on the planet. Reflecting contemporary anthropological interest in material culture studies, Anthropology of Tobacco makes the plant the centre of its own contentious, global story in which, instead of a passive commodity, tobacco becomes a powerful player in a global adventure involving people, corporations and public health. Bringing together a range of perspectives from the social and natural sciences as well as the arts and humanities, Anthropology of Tobacco weaves stories together from a range of historical, cross-cultural and literary sources and empirical research. These combine with contemporary anthropological theories of agency and cross-species relationships to offer fresh perspectives on how an apparently humble plant has progressed to world domination, and the consequences of it having done so. It also considers what needs to happen if, as some public health advocates would have it, we are seriously to imagine ‘a world without tobacco’. This book presents students, scholars and practitioners in anthropology, public health and social policy with unique and multiple perspectives on tobacco-human relations. Andrew Russell is Associate Professor in Anthropology at Durham University, UK, where he is a member of the Anthropology of Health Research Group. His research and teaching spans the sciences, arts and humanities, and mixes both theoretical and applied aspects. He has conducted research in Nepal, the UK and worldwide. Earlier books include The Social Basis of Medicine, which won the British Medical Association’s student textbook of the year award in 2010, and a number of edited volumes, the latest of which (co-edited with Elizabeth Rahman) is The Master Plant: Tobacco in Lowland South America. -

Magazine 2 Innovatie Is Van Iedereen

2– 2017 MAGAZINE INNOVATIE IS WILLEN INVESTEREN IN BEKENDE NAAM IN PEIJS STOPT ALS EN DURVEN MARINE TESTEN VOORZITTER NIDV NIDV SYMPOSIUM & TENTOONSTELLING INHOUD Innovatie Innovatie is willen en durven, zegt kolonel ir. Robert Meeuwsen, hoofd Innovatie van de Koninklijke Landmacht. Daarbij moet een organisatie leren om niet te krampachtig aan processen vast te houden. Over innovatie bij Defensie, Politie en Veiligheid en Justitie gaat dit NIDV Magazine. info: www.nidv.eu Voelen, zien en beleven 4 Innovatie is van iedereen 10 Sun Test Systems wereldwijd 20 14 Nulkes’ Notes 26 Defensie moet ambitieus investeren in de Koninklijke Marine. Colofon 27 24 Bijna vijf jaar was Karla Peijs bestuursvoorzitter van de NIDV. Ahoy Rotterdam - 30 november 2017 Bij de voorplaat: Minister van Defensie Jeanine Hennis-Plasschaert nam medio mei 2017 het rapport over de marinebouw in ontvangst van NIDV-voorzitter Karla Peijs. Het belang van het maritieme cluster voor Nederland als zeevarende natie is groter dan ooit, aldus de coalitie van NIDV, VNO-NCW, Netherlands Maritime Technology en Nederland Maritiem Land. Foto: Georges Hoeberechts NIDV MAGAZINE I JUNI 2017, NR. 2 3 De krijgsmacht moderniseert voortdurend. Defensie gebruikt daarvoor zo’n 20 procent van haar budget. Dat is nodig om ook in de toekomst Nederland te verdedigen, civiele diensten te ondersteunen en de strijd aan te gaan met terroristen en piraten. In Soesterberg opende de Koninklijke Landmacht een ‘slimme basis’ om te voelen, zien en beleven. Tekst en foto’s: Riekelt Pasterkamp Landmacht opent ‘slimme basis’ in Soesterberg Voelen, zien en beleven Basis compleet met wachttorens Op 13 juni overhandigde Ineke Dezentjé Hammink, voorzitter van FME, in Soesterberg het bordje Fieldlab en Hesco’s – met stenen afgevulde Smart Base aan de plaatsvervangend commandant van de Koninklijke Landmacht, generaal-majoor Martin zandzakken ter bescherming. -

Promoting Good Governance in the Security Sector: Principles and Challenges

Promoting Good Governance in the Security Sector: Principles and Challenges Mert Kayhan & Merijn Hartog, editors 2013 GREENWOOD PAPER 28 Promoting Good Governance in the Security Sector: Principles and Challenges Editors: Mert Kayhan and Merijn Hartog First published in February 2013 by The Centre of European Security Studies (CESS) Lutkenieuwstraat 31 A 9712 AW Groningen The Netherlands Chairman of the Board: Peter Volten ISBN: 978-90-76301-29-7 Copyright © 2013 by CESS All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Centre for European Security Studies (CESS) is an independent institute for research, consultancy, education and training, based in the Netherlands. Its aim is to promote transparent, accountable and effective governance of the security sector, broadly defined. It seeks to advance democracy and the rule of law, help governments and civil society face their security challenges, and further the civilized and lawful resolution of conflict. The Man behind the Greenwood Papers Resting his fists on the lectern, he would fix his audience with a glare and pronounce: “REVEAL, EXPLAIN AND JUSTIFY.” It was his golden rule of democratic governance. David Greenwood was born in England in 1937 and died in 2009 in Scotland. He first worked for the British Ministry of Defence, then went on to teach political economy at Aberdeen University, where he later became the director of the Centre for Defence Studies. In 1997, David Greenwood joined the Centre for European Security Studies in the Netherlands as its Research Director. -

Países Bajos

20 PAÍSES BAJOS NUEVO GOBIERNO El pasado 14 de octubre se formó y posó junto a la Reina Beatriz el nuevo Gabinete Rutte, de coalición entre el partido Liberal, VVD, y el partido Democristiano, CDA, que gobernará con el apoyo del Partido para la Libertad, PVV, de tendencia antimusulmana. Tras unas elecciones anticipadas, como consecuencia de la ruptura de la coalición gubernamental anterior, y tras muchos meses de negociaciones por el difícil tablero parlamentario que resultó de las urnas, por fin se alcanzaron unos acuerdos para formar un gobierno de derechas en minoría con el apoyo de un partido de tendencia antimusulmana. El Ministro Presidente es Marc Rutte, líder del partido más votado, el partido Liberal y actualmente bien valorado por la juventud y el Vicepresidente es Máxime Verhagen, líder del Partido Demócrata-Cristiano, CDA. El nuevo ejecutivo está integrado por 12 Ministros y 8 Secretarios de Estado. El número de miembros del gobierno se ha reducido a 20; anteriormente eran 27. Hay seis ministros del VVD y otros seis del CDA. Además, hay 8 secretarios de estado, cuatro de cada uno de los partidos de la coalición. El número de ministerios ha bajado de 13 a 11. Los Ministerios de Asuntos Económicos (EZ) y el de Agricultura, Naturaleza y Calidad Alimentaria (LNV) se han unido para formar el nuevo Ministerio de Economía e Innovación. Por otra parte se han fusionado el Ministerio de Transporte y de Regulación de las Aguas (MOT) y el Ministerio de Vivienda, Ordenación Territorial y Medio Ambiente, para constituir el nuevo Ministerio de Infraestructura y Medio Ambiente.