Library Services for the High School Student

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HURRICANE HARVEY RELIEF EFFORTS Supporting Immigrant Communities

HURRICANE HARVEY RELIEF EFFORTS Supporting Immigrant Communities Guide to Disaster Assistance Services for Immigrant Houstonians Mayor’s Office of New Americans & Immigrant Communities Mayor’s Office of Public Safety Office of Emergency Management A Message from the City of Houston Mayor’s Office of New Americans and Immigrant Communities To All Houstonians and Community Partners, In the aftermath of a natural disaster of unprecedented proportions, the people of Houston have inspired the nation with their determination, selflessness, and camaraderie. Hurricane Harvey has affected us all deeply, and the road to recovery will surely be a long one. We can find hope, however, in the ways in which Houstonians of all ethnic, racial, national, religious, and socioeconomic backgrounds have come together to help one another. This unity in diversity is one of the things that makes Houston such a special city. Our office is here to offer special support to the thriving immigrant community that forms such an integral part of this city and to help immigrants to address the unique challenges they face in the wake of this natural disaster. For our community partners, we recognize the critical role you play in the process of helping Houstonians recover from the devastating effects of Hurricane Harvey. Non- profit and community-based organizations are on the front lines of service delivery across Houston, and we want to ensure that you have the information and resources you need to help your communities recover. This guide—which will soon be available as an app—provides detailed information about the types of federal, state, and local disaster-assistance services available and where you can go to access those services. -

Harris County Public Library Records CR57 (1920 – 2014, Bulk: 1920 - 2000)

Harris County Archives Houston, Texas Finding Aid Harris County Public Library Records CR57 (1920 – 2014, Bulk: 1920 - 2000) Size: 31 cubic feet, 16 items Accession Numbers: 2007.005, Restrictions on Access: None 2009.003, 2015.016, 2016.003, Restrictions on Use: None 2016.004, 2017.001, 2017.003 Acquisition: Harris County Public Processed by: AnnElise Golden 2008; Library, 2007, 2009, 2015, 2016, 2017. Sarah Canby Jackson, 2015, 2021; Terrin Rivera 2019 – 2021. Citation: [Identification of Item], Harris County Public Library Records, Harris County Archives, Houston, Texas. Agency History: In the fall of 1920 a campaign for library services began for rural Harris County. Under the direction of attorney Arthur B. Dawes with assistance from the Dairy Men’s Association, Julia Ideson, Librarian of the Houston Public Library, I.H. Mowery of Aldine, Miss Christine Baker of Barker, County Judge Chester H. Bryan, Edward F. Pickering, and Rev. Harris Masterson, a citizen’s committee circulated petitions for a county library throughout Harris County. Dawes presented the plans and petitions signed by Harris County qualified voters to the Commissioners Court and, with skepticism, the Commissioners Court ordered a budget of $6500.00 for the county library for a trial period of one year. If the library did not succeed, the Commissioners Court would not approve a budget for a second year. The Harris County Commissioners Court appointed its first librarian, Lucy Fuller, in May 1921, and with an office on the fifth floor of the Harris County Court House, the Harris County Public Library was in operation. At the close of the year, the HCPL had twenty- six library branches and book wagon stations in operation, 3,455 volumes in the library, and 19,574 volumes in circulation. -

Federal Depository Library Directory

Federal Depositoiy Library Directory MARCH 2001 Library Programs Service Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office Wasliington, DC 20401 U.S. Government Printing Office Michael F. DIMarlo, Public Printer Superintendent of Documents Francis ]. Buclcley, Jr. Library Programs Service ^ Gil Baldwin, Director Depository Services Robin Haun-Mohamed, Chief Federal depository Library Directory Library Programs Service Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office Wasliington, DC 20401 2001 \ CONTENTS Preface iv Federal Depository Libraries by State and City 1 Maps: Federal Depository Library System 74 Regional Federal Depository Libraries 74 Regional Depositories by State and City 75 U.S. Government Printing Office Booi<stores 80 iii Keeping America Informed Federal Depository Library Program A Program of the Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO) *******^******* • Federal Depository Library Program (FDLP) makes information produced by Federal Government agencies available for public access at no fee. • Access is through nearly 1,320 depository libraries located throughout the U.S. and its possessions, or, for online electronic Federal information, through GPO Access on the Litemet. * ************** Government Information at a Library Near You: The Federal Depository Library Program ^ ^ The Federal Depository Library Program (FDLP) was established by Congress to ensure that the American public has access to its Government's information (44 U.S.C. §§1901-1916). For more than 140 years, depository libraries have supported the public's right to know by collecting, organizing, preserving, and assisting users with information from the Federal Government. The Government Printing Office provides Government information products at no cost to designated depository libraries throughout the country. These depository libraries, in turn, provide local, no-fee access in an impartial environment with professional assistance. -

30Th Anniversary of the Center for Public History

VOLUME 12 • NUMBER 2 • SPRING 2015 HISTORY MATTERS 30th Anniversary of the Center for Public History Teaching and Collection Training and Research Preservation and Study Dissemination and Promotion CPH Collaboration and Partnerships Innovation Outreach Published by Welcome Wilson Houston History Collaborative LETTER FROM THE EDITOR 28½ Years Marty Melosi was the Lone for excellence in the fields of African American history and Ranger of public history in our energy/environmental history—and to have generated new region. Thirty years ago he came knowledge about these issues as they affected the Houston to the University of Houston to region, broadly defined. establish and build the Center Around the turn of the century, the Houston Public for Public History (CPH). I have Library announced that it would stop publishing the been his Tonto for 28 ½ of those Houston Review of History and Culture after twenty years. years. Together with many others, CPH decided to take on this journal rather than see it die. we have built a sturdy outpost of We created the Houston History Project (HHP) to house history in a region long neglectful the magazine (now Houston History), the UH-Oral History of its past. of Houston, and the Houston History Archives. The HHP “Public history” includes his- became the dam used to manage the torrent of regional his- Joseph A. Pratt torical research and training for tory pouring out of CPH. careers outside of writing and teaching academic history. Establishing the HHP has been challenging work. We In practice, I have defined it as historical projects that look changed the format, focus, and tone of the magazine to interesting and fun. -

Rice Centennial Preparations Draw on Fondren Resources

NEWS FROM FONDREN Volume 21, No. 1 • Fall 2011 Rice Centennial Preparations Draw on Fondren Resources It’s no secret that Rice University will Perhaps one of the busiest places provided direct support for the celebrate its centennial Oct. 10–14, this year has been the Woodson Centennial Celebration committee, 2012. Many events will mark this Research Center, where staff have assisting with projects such as their milestone, including an academic been helping prepare for these online timeline, and Melissa Kean, procession, a statue dedication, events as well as other aspects of the university historian, can be seen in the the Centennial Lecture Series, celebration. From helping the Athletics Woodson almost daily as she prepares performances, exhibits, receptions Department to the School of Natural posts for her Historian’s Blog, http:// and parties, as well as Homecoming & Sciences to individual students, Lee ricehistorycorner.wordpress.com/ Reunion weekend. Preparing for such Pecht, head of special collections author/melissakean/, which features a momentous occasion is an immense at Woodson, and Amanda Focke, vintage photographs, interesting task, requiring contributions from assistant head of special collections, historical facts and notable campus many Rice community members. have been very involved in all aspects happenings through the years. of the upcoming celebration. In August, Kean posted about the Recently, Pecht and Focke have trophy case located in the main entry been assisting undergraduate students of Rice Memorial Center describing Eli Spector ’14 and Rohini Sigireddi an exhibit full of “weird pieces of ’14, who were awarded a 2011 equipment” that Pecht and Mary Bixby, Envision Grant through Leadership director of Friends of Fondren, put Rice to embrace Rice’s history and together to replace a display that hadn’t present it to the world through a Rice Wiki website and various CONTINUED ON PAGE 2 podcasts on iTunes. -

NEWS from FONDREN • Spring 2021 3 OUTREACH

NEWS FROM FONDREN Volume 30, No. 2 • Spring 2021 Fondren Safely Monitors Building Traffic In order to maintain social distancing and pandemic safety measures, Fondren has introduced a new piece of software called Waitz. Jeff Koffler, web/graphic designer, explained, “Waitz uses a custom code to detect wireless device signals and count the number of people in a zone. It takes some configuration at the beginning but becomes more accurate after a few days. It’s a little device that plugs into an outlet and communicates back to the website hub and app.” Features include: Real–time occupancy data about Fondren’s popular, open study areas: Basement DMC/Gov Docs First-floor reading rooms Second-floor mezzanine Third-floor Brown Fine Arts Sixth floor Ability to track busy/less-busy times in the library Mobile/web interface to view live data, available at library.rice.edu https://waitz.io/rice Secure and anonymous data Sara Lowman, vice provost and university librarian, shared, “The Waitz program will enable the library to track building occupancy in the most heavily used study areas of the library. Students have expressed concern about health and safety in light of the COVID-19 pandemic — this software will enable us to proactively address students’ concerns regarding their safety and social distancing standards.” Debra Kolah Head of User Experience CHECK IT OUT! Pg. 3 Interviews Preserve Rice Pandemic Experiences Pg. 7 Course Reserves Move into Canvas Pg. 12 An Irish Family Settles in 19th Century Texas Pg. 14 Student Research Illuminates Local History of Slavery COLLABORATION Expanding Histories: Shining a Light on Underserved Communities When the COVID-19 pandemic forced staff at Fondren Library to work remotely last spring, the team at the Woodson Research Center (WRC) increased its focus on digital projects. -

Second Ward COMPLETE COMMUNITIES in April of 2017, Mayor Sylvester Turner Announced the Very Different Strengths and Challenges

SUSTAINABLE · Safe · Unified · Caring · Compassionate · CONNECTED · Kind · Diverse · Equitable · Inclusive · Involved · Integrated · Engaged · Resilient · Sustainable · Thriving · Revitalized · Helpful · AFFORDABLE · Self-Sufficient · Prosperous · Resourceful · Holistic · GOOD INFRASTRUCTURE · Peaceful · Welcoming · Accepting · Active · Healthy · Supportive · Full · Green · HEALTHY · Connected · Peaceful · Affordable · Clean · Social · SAFE · Complete · Authentic · Committed · Educated · Enriching · Empowered · Cooperative · ECONOMICALLY STRONG · Accessible · Mobile · Comprehensive · BEAUTIFUL · Culturally Rich · Whole · QUALITY SCHOOLS · SUSTAINABLE · Safe · Unified · Caring · Compassionate · CONNECTED · Kind · Diverse · Equitable · Inclusive · Involved · Integrated · Engaged · Resilient · Sustainable · Thriving · Revitalized · Helpful · AFFORDABLE · Self-Sufficient · Prosperous · Resourceful · Holistic · GOOD INFRASTRUCTURE · Peaceful · Welcoming · Accepting · Active · Healthy · Supportive · Full · Green · HEALTHY · Connected · Peaceful · Affordable · Clean · Social · SAFE · Complete · Authentic · Committed · Educated · Enriching · Empowered · Cooperative · ECONOMICALLY STRONG · Accessible · Mobile · Comprehensive · BEAUTIFUL · Culturally Rich · Whole · QUALITY SCHOOLS · SUSTAINABLE · Safe · Unified · Caring · Compassionate · CONNECTED · Kind · Diverse · Equitable · Inclusive · Involved · Integrated · Engaged · Resilient · Sustainable · Thriving · Revitalized · Helpful · AFFORDABLE · Self-Sufficient · Prosperous · Resourceful · Holistic -

Table of Contents & Quick Facts

TABLE OF CONTENTS & QUICK FACTS THIS IS RICE 1-25 GENERAL INFORMATION Table of Contents & Quick Facts 1 Location Houston, Texas THIS IS RICE University Section 2-19 Enrollment 5,008 INTRO Administration/Athletics Department 20-24 Founded 1891 (First Classes in 1912) COACHES Conference USA 25 Nickname Owls Mascot Sammy the Owl OWLS INTRODUCTION 26-29 Colors Blue and Gray HISTORY Jake Hess Stadium 26 President David W. Leebron Rice Reunion Recap 27 Director of Athletics Chris Del Conte 2008 Outlook, Roster & Schedule 28-29 Faculty Representative Dr. James Castañeda Conference Conference USA COACHING STAFF 30-32 Began C-USA Competition 2005 Head Coach Roger White 30 Assistant Coach Kristina Kraszewski 31 TENNIS STAFF Volunteer Coach Mashona Washington 31 Head Coach (Alma Mater, Year) Roger White (Abilene Christian, 2003) Trainer Layne Schramm 32 Record at Rice (Seasons) 69-79 (6) Racquet Stringer Ken Mize 32 Career Record (Seasons) Same SID Matt Dunaway 32 Best Time for Interview Contact SID Assistant Head Coach (Alma Mater, Year) Kristina Kraszewski (Washington, 2001) MEET THE 2007-08 OWLS 33-39 Year at Rice 2nd Season Christine Dao 33 Volunteer Coach Mashona Washington Tiffany Lee 34 Year at Rice 2nd Season Emily Braid 35 Dominique Karas 36 TEAM INFORMATION Julie Chao 37 2006-07 Record 8-15 Rebecca Lin 38 2006-07 Conference USA Record (Finish) 0-2 (Seeded 10nd) Varsha Shiva-Shankar 39 2007 Conference USA Tournament Finish Semifinals (Marshall) Rebekka Hanle 39 2007 Postseason NA Jessica Jackson 39 Home 5-8 Away 1-5 SEASON REVIEW/HISTORY 40-48 Neutral 2-2 2006-07 Stats 40 Nationally Ranked 2-14 Series History & Results 41 Region 2-5 Athletic Honors 42-43 Letterwinners Returning/Lost 6/4 Academic Honors 44-45 Newcomers 2 2006 Conference USA Champions 46-47 All-Time Letterwinners 48 HOME COURT INFORMATION Name Jake Hess Tennis Stadium WWW.RICEOWLS.COM 1 JAKE HESS STADIUM aming a court at the Jake Hess Tennis Stadium is an unique and THIS IS RICE ne of the finest facilities in the southwest, the Jake Hess Tennis Stadium gives the Owls a definite home-court advantage. -

Lynda Crist and the Jefferson Davis Papers: the Library Connection

NEWS FROM FONDREN Volume 24, No. 2 r Spring 2015 Lynda Crist and the Jefferson Davis Papers: The Library Connection As the completion of the Jefferson Davis there continue to scout eBay for primary Papers and her career at Rice approach, resources that even now still come to light. I sat with current editor Lynda Crist to _________________________________ learn about the library’s role in her work. ,VWKHUHDQ\WKLQJHOVH\RXZRXOG _________________________________ OLNHUHDGHUVWRNQRZDERXWWKLV Generally, what is the role of library long collaboration? resources in a project like the For the first seven years of the project, Davis Project? Haskell M. Monroe, the first editor, We couldn’t live outside the context traveled the South with a copy machine, of a research library. We are heavy users well before those were standard equipment of many library departments, including in libraries. The project has benefited interlibrary loan (ILL), technical services, from a series of graduate student interns, the Kelley Center and the Woodson some of whom have pursued careers in Research Center (WRC). We also have public history, editing, museum work and used the Clayton Library, especially publishing. Graduate students, volunteers before the existence of www.ancestry. and all the editorial staff members sat com and the online release of Confederate Portrait to be donated to Beauvoir, and read microfilmed newspapers in service records, plantation records and Jefferson Davis’ home. their entirety, gathering references to the collected papers of contemporaries Davis. All that had to be done before we produced by projects similar to ours. We newspapers, often several titles to a reel. -

2018-2019 Impact Report

P AIR EMPOWERING REFUGEE YOUTH 2018-2019 IMPACT REPORT PAIR's educational mentoring programs enable refugee youth to navigate American society, reach their academic potential, and become community leaders. 2018-2019 IMPACT REPORT | PAIR HOUSTON PAIR HOUSTON LETTER FROM OUR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR As school bells rang in the 2018-2019 academic year, over 300 refugee students from across the globe awaited their after-school oasis. Students excitedly shared their summer experiences: PAIR summer camp and field trips, internships and preparation for college. It’s in moments like these, where refugee students from over 30 different countries and speaking as many languages at home are stronger together. PAIR programs create space for young refugees to spend time with friends, to learn from mentors, and to create goals for their lives as leaders and future citizens. Throughout the school year and during academic breaks, PAIR youth development staff and volunteer mentors meet with refugee youth at five Houston public schools. Thanks to PAIR’s intensive and caring approach in its programs, hundreds of bright futures are emerging. Jennifer Garmon, LMSW While refugee students grapple with navigating culture and school, life and Executive Director academic skills built through PAIR programs forge new paths to a successful PAIR - Partnership for the life in the United States. Creative writing workshops cultivate students’ English Advancement development and self-esteem. High school "boot camp" summer sessions & Immersion of Refugees prepare middle school students for the academic rigor of high school. Computer literacy and online safety curricula equip students for lives in the digital age. Just as each refugee’s experiences are uniquely their own, PAIR tailors program and lessons to meet the needs of each student and school community. -

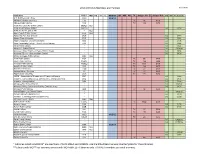

2019-20 MALA Members and Partners * Libraries Noted As MOBIUS* Are

2019-20 MALA Members and Partners 10/2/2019 Institution OCLC MO KS IA IL MOBIUS AR NM OK TX Amigos Site ID Amigos Hub CO WY CLiC Code A.T. Still Memorial Library WG1 MOBIUS Abilene Christian University TXC TX 36 WTX Abilene Public Library TXB TX 155 WTX Academie Lafayette School Library MOALC MO Academy 20 School District COPCH CO C314 Academy for Integrated Arts * MO Adair County Public Library KVA MO Adams 12 Five Star Schools DVA CO C878 Adams State University CLZ CO C384 Adams-Arapahoe 28J School District XN0 CO C108 Aims Community College - Jerry A. Kiefer Library CAA CO C884 Akron Public Library * CO C824 Akron R-1 School District * CO C824.as Alamosa Library (Southern Peaks Public Library) * CO C404 Alamosa RE-11J - Alamosa High School * CO C406 Albany Carnegie Public Library MQ2 MO Allen Public Library TOP TX 95 DFW Alpine Public Library TXAPL TX 122 HKB Alvarado Public Library TXADO TX 8801 DFW Amarillo Public Library TAP TX 156 WTX Amberton University TAM TX 27 DFW Amigos Library Services IIC TX 23 DFW Angelo State University ANG TX 19 WTX AORN - Association of Perioperative Registered Nurses DNF CO C886 Arapahoe Community College Library and Learning Commons DVZ CO C874 Arapahoe Library District CO2 CO C214 Arickaree R-2 School District * CO C840.ar Arkansas Valley Correctional Facility General Library * CO C402 Arlington Public Library AR9 TX 98 DFW Arriba-Flagler C-20 School District * CO C836.af Arrowhead Correctional Center * CO C370 Assistive Technology Partners (SWAAAC) * CO C209 Atchison County Library MQ3 MO Aubrey -

Harris County Archives Houston, Texas

Harris County Archives Houston, Texas Finding Aid Harris County Public Library Records CR57 (1920 - 2009) Size: 15.5 cubic feet Accession Numbers: 2007.005, Restrictions on Access: None 2009.003, 2015.016 Restrictions on Use: None Processed by: AnnElise Golden 2008; Acquisition: Harris County Public Sarah Canby Jackson, 2015 Library, 2007, 2009, 2015. Citation: [Identification of Item], Harris County Public Library Records, Harris County Archives, Houston, Texas. Agency History: In the fall of 1920 a campaign for library services began for rural Harris County. Under the direction of attorney Arthur B. Dawes with assistance from the Dairy Men’s Association, Julia Ideson, Librarian of the Houston Public Library, I.H. Mowery of Aldine, Miss Christine Baker of Barker, County Judge Chester H. Bryan, Edward F. Pickering, and Rev. Harris Masterson, a citizen’s committee circulated petitions for a county library throughout Harris County. Dawes presented the plans and petitions signed by Harris County qualified voters to the Commissioners Court and, with skepticism, the Commissioners Court ordered a budget of $6500.00 for the county library for a trial period of one year. If the library did not succeed, the Commissioners Court would not approve a budget for a second year. The Harris County Commissioners Court appointed its first librarian, Lucy Fuller, in May 1921, and with an office on the fifth floor of the Harris County Court House, the Harris County Public Library was in operation. At the close of the year, the HCPL had twenty- six library branches and book wagon stations in operation, 3,455 volumes in the library, and 19,574 volumes in circulation.