Parliament and the Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federation Teacher Notes

Government of Western Australia Department of the Premier and Cabinet Constitutional Centre of WA Federation Teacher Notes Overview The “Federation” program is designed specifically for Year 6 students. Its aim is to enhance students’ understanding of how Australia moved from having six separate colonies to become a nation. In an interactive format students complete a series of activities that include: Discussing what Australia was like before 1901 Constructing a timeline of the path to Federation Identifying some of the founding fathers of Federation Examining some of the federation concerns of the colonies Analysing the referendum results Objectives Students will: Discover what life was like in Australia before 1901 Explain what Federation means Find out who were our founding fathers Compare and contrast some of the colony’s concerns about Federation Interpret the results of the 1899 and 1900 referendums Western Australian Curriculum links Curriculum Code Knowledge & Understandings Year 6 Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS) ACHASSK134 Australia as a Nation Key figures (e.g. Henry Parkes, Edmund Barton, George Reid, John Quick), ideas and events (e.g. the Tenterfield Oration, the Corowa Conference, the referendums) that led to Australia's Federation and Constitution, including British and American influences on Australia's system of law and government (e.g. Magna Carta, federalism, constitutional monarchy, the Westminster system, the Houses of Parliament) Curriculum links are taken from: https://k10outline.scsa.wa.edu.au/home/p-10-curriculum/curriculum-browser/humanities-and-social- sciences Background information for teachers What is Federation? (in brief) Federation is the bringing together of colonies to form a nation with a federal (national) government. -

A Comparison of the Constitutions of Australia and the United States

Buffalo Law Review Volume 4 Number 2 Article 2 1-1-1955 A Comparison of the Constitutions of Australia and the United States Zelman Cowan Harvard Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Zelman Cowan, A Comparison of the Constitutions of Australia and the United States, 4 Buff. L. Rev. 155 (1955). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview/vol4/iss2/2 This Leading Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COMPARISON OF THE CONSTITUTIONS OF AUSTRALIA AND THE UNITED STATES * ZELMAN COWAN** The Commonwealth of Australia celebrated its fiftieth birth- day only three years ago. It came into existence in January 1901 under the terms of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act, which was a statute of the United Kingdom Parliament. Its origin in a 1 British Act of Parliament did not mean that the driving force for the establishment of the federation came from outside Australia. During the last decade of the nineteenth cen- tury, there had been considerable activity in Australia in support of the federal movement. A national convention met at Sydney in 1891 and approved a draft constitution. After a lapse of some years, another convention met in 1897-8, successively in Adelaide, Sydney and Melbourne. -

Australian Federation: Its Aims and Its Possibilities

Australian Federation: Its Aims and its Possibilities Willoughby, Howard A digital text sponsored by New South Wales Centenary of Federation Committee University of Sydney Library Sydney 2001 http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/fed/ © University of Sydney Library. The texts and Images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Source Text: Prepared from the print edition published by Sands & Mcdougall Limited, Collins Street Melbourne 1891 First Published: 1891 Languages: Latin Australian Etexts 1890-1909 prose nonfiction federation 2001 Creagh Cole Coordinator Final Checking and Parsing Australian Federation: Its Aims and its Possibilities With a Digest of the Proposed Constitution, Official Statistics, and a Review of the National Convention by Melbourne Sands & Mcdougall Limited, Collins Street 1891 Preface. THE first portion of this work appeared in the columns of the Melbourne Argus. The republication is at the request of many readers, and with the kind consent of the proprietors of the journal in question. The object in view has been to put principles before the public rather than details, because the subject itself is new to most of us; it has been talked about after public dinners, rather than thought out in the closet; and unless principles are grasped it may not be easy to arrange the compromises on which all federations are founded. In the following pages the writer has endeavoured to state certain vital principles as clearly as was in his power, and to strongly, though fairly, advocate their adoption. For instance, the necessity for a Customs union is maintained throughout. But as a rule his aim is to give both sides of a case, so that the problem may be grasped, and so that federalists who differ may do so with good feeling and with mutual respect, and without injury to the national cause on which so much depends. -

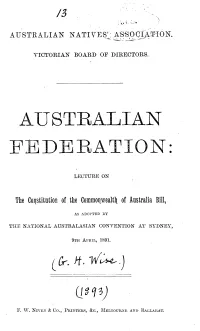

Australian Federation

AUSTRALIAN NATIVES' ASSOCIATION. VICTORIAN BOARD OF DIRECTORS. AUSTRALIAN FEDERATION: LECTURE ON The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia Bill, AS ADOPTED BY THE NATIONAL AUSTRALASIAN CONVENTION AT SYDNEY, 9th April, 1891. Jr. H- TvL«,.J (1*PJ F. W. Niven & Co., Printers, &c., Melbourne and Ballarat. AUSTRALIAN FEDERATION. THE CONSTITUTION OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA. Although now brought within the range of practical politics for the first time, the Federation of Australia is no new subject. Indeed one is surprised on going through the records of Australian politics to find how old it is. It appears almost simultaneously ^vith the foundation in Australia of other colonies than New South Wales. For just as clearly as the early colonists saw that the division of our island continent into separate self-governing colonies was absolutely necessary for the proper development of the material resources of its vast territory, so clearly did they see that the re-union of these separate colonies under a federation, wherebjr they would be united under one national Government without their separate administrations, legislatures, and local patriotisms being extinguished, would be as necessary for the full development of the national life of their people. The first move in the matter was in 1849, when a committee of the British Privy Council, appointed at the instance of Earl Grey, reported on the subject. At that time there were only jthree colonies on the mainland, viz., New South Wales, South Australia, and Western Australia. The report of the committee was adopted by Earl Grey, and a bill to give effect thereto was introduced into the British Parliament in the following year, but meeting with opposition was abandoned. -

Federation of Australia

Pre-1908 Federation of Australia The idea of a federation of the six Australian colonies was occasionally debated among Australian politicians, officials and others from about 1850 onwards, and there was support for the idea in official circles in Britain, especially after the Canadian colonies federated in 1867. The first practical step towards federation was the creation of the Federal Council of Australasia in 1885. It met several times between 1886 and 1899, but it had no executive powers, New South Wales remained aloof, and it was generally ineffective. In October 1889, in a speech at Tenterfield, the veteran New South Wales politician Sir Henry Parkes called for federation, with a strong executive controlled by the Australian people, to ensure that the colonies were properly defended. Following an informal conference in Melbourne in 1890, all the Australian colonies and also New Zealand sent delegates to a convention in Sydney in March 1891. It was chaired by Parkes. A sub-committee comprising Sir Samuel Griffith, Charles Kingston, Edmund Barton and Andrew Inglis Clark drafted a Constitution Bill. However, the colonial legislatures were slow to adopt it and, in particular, there was strong opposition in New South Wales. In 1893 popular support for federation began to grow, with the formation of federation leagues in most colonies and a conference of leagues in Corowa in New South Wales. In 1895 the premiers agreed that another convention should be held, with the delegates directly chosen by the electors. The Federal Convention met in Adelaide in March 1897 and was reconvened in Sydney in September 1897 and Melbourne in January 1898. -

Disciplinary and Ethics Committee

FOOTBALL FEDERATION OF AUSTRALIA DISCIPLINARY AND ETHICS COMMITTEE DETERMINATION OF THE COMMITTEE IN THE FOLLOWING MATTER: Player and club Michael Marrone of Adelaide United Alleged offence Serious unsporting conduct Date of alleged offence 21.11.2017 Occasion of alleged offence Match between Sydney FC and Adelaide United (FFA Cup Final) Date of Disciplinary Notice 22.11.2017 Basis the matter is before A referral: see clause 24.4(b) the Disciplinary Committee Date of Hearing Tuesday 28.11.2017 Date of Determination 30.11.2017 Disciplinary Committee John Marshall SC, Chair Members Lachlan Gyles SC, Deputy Chair Rob Wheatley A. INTRODUCTION 1. This matter concerns an incident which occurred between Michael Marrone (the Player) and a ball-boy where the Player made contact with a ball-boy and the ball- boy finished up on the ground. It is unacceptable for anyone assisting in the conduct of any game to be knocked to the ground by a player, let alone in the A- League or FFA Cup. No previous case which has involved a ball-boy or ball-girl has come before the Committee. Nevertheless, there have been instances where players have made contact with referees and other match officials and in such cases the Committee has applied a zero tolerance approach. Assuming the Player did not intend to knock the ball-boy to the ground, his conduct was nevertheless reckless and it is clearly inappropriate that a young ball-boy finished on the ground and could have been injured as a direct effect of the Player’s actions. 2. The Player’s evidence was that he thought that the ball-boy might not give him the ball “so I was going to have to grab it”. -

Corowa (1893) and Bathurst (1896)

Papers on Parliament No. 32 SPECIAL ISSUE December 1998 The People’s Conventions: Corowa (1893) and Bathurst (1896) Editors of this issue: David Headon (Director, Centre for Australian Cultural Studies, Canberra) Jeff Brownrigg (National Film and Sound Archive) _________________________________ Published and Printed by the Department of the Senate Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031–976X Published 1998 Papers on Parliament is edited and managed by the Research Section, Department of the Senate. Copy editor for this issue: Kay Walsh All inquiries should be made to: The Director of Research Procedure Office Department of the Senate Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (02) 6277 3078 Email: [email protected] ISSN 1031–976X ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Centre for Australian Cultural Studies The Corowa and District Historical Society Charles Sturt University (Bathurst) The Bathurst District Historical Society Cover design: Conroy + Donovan, Canberra Introduction When Henry Parkes delivered his Tenterfield speech in October 1889, declaring federation’s time had come, he provided the stimulus for an eighteen-month period of lively speculation. Nationhood, it seemed, was in the air. The 1890 Australian Federation Conference in Melbourne, followed by the 1891 National Australasian Convention in Sydney, appeared to confirm genuine interest in the national cause. Yet the Melbourne and Sydney meetings brought together only politicians and those who might be politicians. These were meetings, held in the Australian continent’s two most influential cities, which only succeeded in registering the aims and ambitions of a very narrow section of the colonial population. In the months following Sydney’s Convention, the momentum of the official movement was dissipated as the big strikes and severe depression engulfed the colonies. -

The Federation of Australia: 1901

The Federation of Australia: 1901 Activate Prior Knowledge: The birth of the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901: The reasons for Federation. Lesson Focus: A celebration for the European Settlers: Exclusion of the Australian Aboriginal people. Lesson Aim: Students investigate primary resources from the early 1900s and evaluate the events which helped shape the nation's identity. Stage: 3 Outcome: CCS3.2 – Explains the development of the principles of Australian democracy. Indicators: 1. Outlines reasons for federation i.e. unification of the states, transportation and defence. 2. Analyses significant events that have shaped Australia’s identity i.e. the birth of the Australian flag. 3. Evaluates the exclusion of the Aboriginal people during federation and recognizes the importance of a shared history. TEP319 Robey Piggott 1 Revision: Reasons for Federation · Unification of the States: The joining of the 6 independent British Colonies into one Federal Commonwealth. · Transport: Previously all travellers had to change trains at Albury, when travelling between NSW and Victoria. Each Colony's rail lines had a different width track meaning that they had a separate rail system. Commuters had to change trains to cross Colonial borders. Products that were being transported between colonies needed to be loaded and unloaded. · Defence: Each state previously had separate Defence systems which were unified into one Defence system. Instructions: Choose one of the answers below for each hidden Pull word. Then move the rectangle to reveal the correct answer. Choices: A) unified B) British C) colonies The Albury Mail Train, 1900. 2 Other Reasons for Federation ... Instructions: Circle the pictures that indicate Pull reasons for Federation that are racist in nature. -

The High Court of Australia and the Supreme Court of the United States - a Centenary Reflection*

THE DENNING LAW JOURNAL THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA AND THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES - A CENTENARY REFLECTION* The Hon Justice Michael Kirby AC CMG** INTRODUCTION In October 2003 in Melbourne, the High Court of Australia celebrated the centenary of its first sitting. According to the Australian Constitution, it is the “Federal Supreme Court” of the Australian Commonwealth.1 Although the Constitution envisaged the establishment of the High Court, the first sitting of the new court did not take place until a statute had provided for the court and the appointment of its first Justices. They took their seats in a ceremony held in the Banco Court in the Supreme Court of Victoria on 6 October 1903. Exactly a century later, the present Justices assembled in the same courtroom for a sitting to mark the first century of the Court. In the course of the century, the Australian Justices have paid close attention to the decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States. The similarities between the Australian Constitution and that of the United States from which many basic ideas were borrowed made such attention inevitable. For the Australian colonists fashioning their own Constitution, the United States Constitution was “an incomparable model”.2 Indirectly, the Australian colonies owed their existence to the American Revolution and the work of the colonists who met at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787, there establishing a Constitution of shared powers, with a Supreme Court and federal judiciary to uphold the federal compact. But for the loss of the American colonies, it is unlikely that the government of King George III would have been sufficiently interested to * Based on a lecture given to the Washington College of Law, American University, Washington, 24 September 2003. -

Federation of Australia Scavenger Hunt

Federation of Australia Scavenger Hunt Learn more about how the six colonies of Australia united to become the states of the Commonwealth of Australia. Search Federation of Australia article and answer these questions. Find It! 1. What is the Federation of Australia? 2. When did the British government become prepared to grant the request for self-government by the colonies? 3. What issues united the colonies to seek federation? 4. What was the Federal Council? 5. How did the fiscal problem create an obstacle to federation? 6. What were some of the difficulties faced by the Federal Council? 7. What did Henry Parkes’s speech at Tenterfield, New South Wales call for? 8. What did the first draft of the constitution propose? 9. How did Edmund Barton contribute to popularising the federation movement? 10. In what referendum did all colonies vote in favour of federation? Learn More! Learn more about Australia’s first Prime Minister, Sir Edmund Barton. http://www.worldbookonline.com/student/article?id=ar724239 Learn more about the man referred to as the “Father of Federation”, Sir Henry Parkes: http://www.worldbookonline.com/student/article?id=ar753219 Learn what life was like under the colonies in Australia: http://www.worldbookonline.com/student/article?id=ar742153 Learn about the history of events leading to federation in Timelines: http://www.worldbookonline.com/wbtimelines/viewtimelines?source=WB&timelineId=53a430f1e4b 031f3938a67f5 Answer Key 1. Federation of Australia is when six Australian colonies became states of the Commonwealth of Australia. 2. 1850. 3. Colonies were united on several issues, i) controlling immigration of Chinese ii) controlling blackbirding in Queensland iii) Fear of European expansion in neighbouring islands. -

Federation of Australia Scavenger Hunt – World Book Kids

Federation of Australia Scavenger Hunt – World Book Kids Learn more about the Federation of Australia on the World Book Web. Find It! 1. In 1901, what did the six colonies of Australia become? ________________________________________________________________ 2. What issues did some politicians believe would be addressed by forming a union of colonies? ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ 3. What did the draft constitution drawn up at the first federal convention held in Sydney in 1891 propose? ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ 4. In what referendum and in what year did all colonies support the draft constitution and plan for federation? ________________________________________________________________ 5. When did the Commonwealth of Australia come into being? ________________________________________________________________ Did you know? - Sir Henry Parkes is also known as the “Father of Federation” because of the role he played in urging the six Australian colonies to form a federal union. - The draft constitution of 1891 was the foundation for what would eventually become Australia’s constitution. - Sir Edmund Barton was Australia’s first Prime Minister. Learn More! - Learn more about Sir Henry Parkes here: http://www.worldbookonline.com/kids/home#article/ar835555 - Learn more about Australia’s constitution here: http://www.worldbookonline.com/kids/home#article/ar840373 - Learn more about Sir Edmund Barton here: http://www.worldbookonline.com/kids/home#article/ar832060 - View a Timeline of events leading to Australia’s Federation, here: http://www.worldbookonline.com/wbtimelines/viewtimelines?source=WB&timel ineId=53a430f1e4b031f3938a67f5 Federation of Australia Scavenger Hunt | World Book Kids Answer Key 1. In 1901, the six colonies of Australia became the states of the Commonwealth of Australia. 2. Colonies had certain economic and social issues that affected them all. -

Australia (1994)

Australia National Affairs A HE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY (ALP), led by Prime Minister Paul Keating, continued in office throughout 1992. The opposing federal coalition of the Liberal and National parties was led by Dr. John Hewson. In state elections in October, the ALP retained power in Queensland but lost to the Liberals in Victoria and Western Australia. Economic issues dominated political debate at all levels, for the nation was still suffering under a severe recession, with unemployment higher than at any time since the Great Depression. Israel and the Middle East Addressing the biennial conference of the Zionist Federation of Australia (ZFA) in May, Prime Minister Keating maintained that Australia's policy toward the Arab-Israeli dispute was "a balanced one which takes account of political realities in the region. Australia is not only committed to Israel's security, but also recognizes the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination. This allows, logically, for the possibility of their own independent state if they so choose." Only a few days earlier, the government had announced a decision to lift the ban on official contact with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) that was im- posed by the Hawke administration during the Gulf War. According to Keating, this decision was "consistent with our long-established aim of encouraging the forces of moderation rather than extremism within the PLO." There had been no change in the government's basic policy, he said. "We do not accept the PLO's claim to be the sole representative of the Palestinian people, but we do accept that the organization represents the view of a significant proportion of them." He added, "Australia has long expressed its opposition to Israel's continued settlement activity in the occupied territories.