Introduction: the Desire Called Postcolonial Science Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/65f2825x Author Young, Mark Thomas Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Mark Thomas Young June 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sherryl Vint, Chairperson Dr. Steven Gould Axelrod Dr. Tom Lutz Copyright by Mark Thomas Young 2015 The Dissertation of Mark Thomas Young is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As there are many midwives to an “individual” success, I’d like to thank the various mentors, colleagues, organizations, friends, and family members who have supported me through the stages of conception, drafting, revision, and completion of this project. Perhaps the most important influences on my early thinking about this topic came from Paweł Frelik and Larry McCaffery, with whom I shared a rousing desert hike in the foothills of Borrego Springs. After an evening of food, drink, and lively exchange, I had the long-overdue epiphany to channel my training in musical performance more directly into my academic pursuits. The early support, friendship, and collegiality of these two had a tremendously positive effect on the arc of my scholarship; knowing they believed in the project helped me pencil its first sketchy contours—and ultimately see it through to the end. -

Carleton University Winter 2017 Department of English ENGL 2906

Carleton University Winter 2017 Department of English ENGL 2906 B Culture and Society: Gothic and Horror Prerequisite(s): 1.0 credit in ENGL at the 1000 level or permission of the Department Tuesdays 6:05 – 8:55 pm 182 Unicentre Instructor: Aalya Ahmad, Ph.D. Email: [email protected] Office: 1422 Dunton Tower Office Hours: please email me for an appointment Course Description: This course is an overview of Gothic and Horror fiction as literary genres or fictional modes that reflect and play with prevalent cultural fears and anxieties. Reading short stories that range from excerpts from the eighteenth-century Gothic novels to mid-century weird fiction to contemporary splatterpunk stories, students will also draw upon a wide range of literary and cultural studies theories that analyze and interpret Gothic and horror texts. By the end of this course, students should have a good grasp of the Gothic and Horror field, of its principal theoretical concepts, and be able to apply those concepts to texts more generally. Trigger Warning: This course examines graphic and potentially disturbing material. If you are triggered by anything you experience during this course and require assistance, please see me. Texts: All readings are available through the library or on ARES. Please note: where excerpts are indicated, students are also encouraged to read the entire text. Evaluation: 15% Journal (4 pages plus works cited list) due January 31 This assignment is designed to provide you with early feedback. In a short journal, please reflect on what you personally have found compelling about Gothic or horror fiction, including a short discussion of a favourite or memorable text(s). -

SFRA Newsletter 259/260

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 12-1-2002 SFRA ewN sletter 259/260 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 259/260 " (2002). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 76. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/76 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #2Sfl60 SepUlec.JOOJ Coeditors: Chrlis.line "alins Shelley Rodrliao Nonfiction Reviews: Ed "eNnliah. fiction Reviews: PhliUp Snyder I .....HIS ISSUE: The SFRAReview (ISSN 1068- 395X) is published six times a year Notes from the Editors by the Science Fiction Research Christine Mains 2 Association (SFRA) and distributed to SFRA members. Individual issues are not for sale. For information about SFRA Business the SFRA and its benefits, see the New Officers 2 description at the back of this issue. President's Message 2 For a membership application, con tact SFRA Treasurer Dave Mead or Business Meeting 4 get one from the SFRA website: Secretary's Report 1 <www.sfraorg>. 2002 Award Speeches 8 SUBMISSIONS The SFRAReview editors encourage Inverviews submissions, including essays, review John Gregory Betancourt 21 essays that cover several related texts, Michael Stanton 24 and interviews. Please send submis 30 sions or queries to both coeditors. -

THE 2016 DELL MAGAZINES AWARD This Year’S Trip to the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Was Spent in a Whirl of Activity

EDITORIAL Sheila Williams THE 2016 DELL MAGAZINES AWARD This year’s trip to the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts was spent in a whirl of activity. In addition to academic papers, author readings, banquets, and the awards ceremony, it was a celebration of major life events. Thursday night saw a surprise birthday party for well-known SF and fantasy critic Gary K. Wolfe and a compelling memorial for storied editor David G. Hartwell. Sunday morning brought us the beautiful wedding of Rebecca McNulty and Bernie Goodman. Rebecca met Bernie when she was a finalist for our annual Dell Magazines Award for Undergraduate Ex- cellence in Science Fiction and Fantasy Writing several years ago. Other past finalists were also in attendance at the conference. In addition to Re- becca, it was a joy to watch E. Lily Yu, Lara Donnelly, Rich Larson, and Seth Dickin- son welcome a brand new crop of young writers. The winner of this year’s award was Rani Banjarian, a senior at Vanderbilt University. Rani studied at an international school in Beirut, Lebanon, before coming to the U.S. to attend college. Fluent in Arabic and English, he’s also toying with adding French to his toolbox. Rani is graduating with a duel major in physics and writing. His award winning short story, “Lullabies in Arabic” incorporates his fascination with memoir writing along with a newfound interest in science fiction. My co-judge Rick Wilber and I were once again pleased that the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts and Dell Magazines cosponsored Rani’s expense-paid trip to the conference in Orlando, Florida, and the five hundred dollar prize. -

The Aqueduct Gazette Top Stories Filter House Co-Winner of the Tiptree H Filter House Wins the Tiptree on April 26, 2009, the James Tiptree, Jr

Spring/Summer 2009 Volume 5 The Aqueduct Gazette Top Stories Filter House Co-Winner of the Tiptree H Filter House Wins the Tiptree On April 26, 2009, The James Tiptree, Jr. H New Essay Collection from Literary Award Council announced that the Ursula K. Le Guin 2008 Tiptree Award will be going to Patrick Special Features Ness’s young adult novel The Knife of Never Letting Go and Nisi Shawl’s Filter House, an H Hanging out along the Aqueduct…, by Nisi Shawl Aqueduct Press book. page 9 The Tiptree Award, an annual literary prize H L. Timmel Duchamp for science fiction or fantasy “that expands or Interviews Liz Henry about explores our understanding of gender,” will The WisCon Chronicles, Vol. 3 be presented on Memorial Day weekend at page 6 WisCon in Madison, Wisconsin. Each winner H Gwyneth Jones writes about will receive $1000 in prize money, an original The Buonarotti Quartet artwork created specifically for the winning page 2 novel or story, and a confection, usually choco- H Three Observations and a late. The 2008 jurors were Gavin J. Grant Dialogue by Sylvia Kelso page 2 (chair), K. Tempest Bradford, Leslie Howle, Roz Kaveney, and Catherynne M. Valente. In Other News The award is named for Alice B. Sheldon, who wrote under the pseudonym H Aqueduct Celebrates James Tiptree, Jr. By her impulsive choice of a masculine pen name, Sheldon 5th Anniversary cont. on page 5 page 8 H New Spring Releases New from Aqueduct: Ursula K. Le Guin, page 12 Cheek by Jowl Talks and Essays about How and Why Fantasy Matters The monstrous homogenization of our world has now almost destroyed the map, any map, by making every place on it exactly like every other place, and leaving no blanks. -

Creolisation and Black Women's Subjectivities in the Diasporic Science Fiction of Nalo Hopkinson Jacolie

Haunting Temporalities: Creolisation and Black Women's Subjectivities in the Diasporic Science Fiction of Nalo Hopkinson Jacolien Volschenk This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, the Department of English, University of the Western Cape Date submitted for examination: 11 November 2016 Names of supervisors: Dr Alannah Birch and Prof Marika Flockemann i Keywords Diasporic science fiction, temporal entanglement, creolisation, black women’s subjectivities, modernity, slow violence, technology, empire, slavery, Nalo Hopkinson Abstract This study examines temporal entanglement in three novels by Jamaican-born author Nalo Hopkinson. The novels are: Brown Girl in the Ring (1998), Midnight Robber (2000), and The Salt Roads (2004). The study pays particular attention to Hopkinson’s use of narrative temporalities, which are shape by creolisation. I argue that Hopkinson creatively theorises black women’s subjectivities in relation to (post)colonial politics of domination. Specifically, creolised temporalities are presented as a response to predatory Western modernity. Her innovative diasporic science fiction displays common preoccupations associated with Caribbean women writers, such as belonging and exile, and the continued violence enacted by the legacy of colonialism and slavery. A central emphasis of the study is an analysis of how Hopkinson not only employs a past gaze, as the majority of both Caribbean and postcolonial writing does to recover the subaltern subject, but also how she uses the future to reclaim and reconstruct a sense of selfhood and agency, specifically with regards to black women. Linked to the future is her engagement with notions of technological and social betterment and progress as exemplified by her emphasis on the use of technology as a tool of empire. -

The Virtual Worlds of Japanese Cyberpunk

arts Article New Spaces for Old Motifs? The Virtual Worlds of Japanese Cyberpunk Denis Taillandier College of International Relations, Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto 603-8577, Japan; aelfi[email protected] Received: 3 July 2018; Accepted: 2 October 2018; Published: 5 October 2018 Abstract: North-American cyberpunk’s recurrent use of high-tech Japan as “the default setting for the future,” has generated a Japonism reframed in technological terms. While the renewed representations of techno-Orientalism have received scholarly attention, little has been said about literary Japanese science fiction. This paper attempts to discuss the transnational construction of Japanese cyberpunk through Masaki Goro’s¯ Venus City (V¯ınasu Shiti, 1992) and Tobi Hirotaka’s Angels of the Forsaken Garden series (Haien no tenshi, 2002–). Elaborating on Tatsumi’s concept of synchronicity, it focuses on the intertextual dynamics that underlie the shaping of those texts to shed light on Japanese cyberpunk’s (dis)connections to techno-Orientalism as well as on the relationships between literary works, virtual worlds and reality. Keywords: Japanese science fiction; cyberpunk; techno-Orientalism; Masaki Goro;¯ Tobi Hirotaka; virtual worlds; intertextuality 1. Introduction: Cyberpunk and Techno-Orientalism While the inversion is not a very original one, looking into Japanese cyberpunk in a transnational context first calls for a brief dive into cyberpunk Japan. Anglo-American pioneers of the genre, quite evidently William Gibson, but also Pat Cadigan or Bruce Sterling, have extensively used high-tech, hyper-consumerist Japan as a motif or a setting for their works, so that Japan became in the mid 1980s the very exemplification of the future, or to borrow Gibson’s (2001, p. -

'Race' and Technology in Nalo Hopkinson's Midnight Robber

This article was downloaded by: [University of Cambridge] On: 22 October 2014, At: 02:40 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK African Identities Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cafi20 Vanishing bodies: ‘race’ and technology in Nalo Hopkinson's Midnight robber Elizabeth Boyle a a University of Chester , Chester, UK Published online: 21 May 2009. To cite this article: Elizabeth Boyle (2009) Vanishing bodies: ‘race’ and technology in Nalo Hopkinson's Midnight robber , African Identities, 7:2, 177-191, DOI: 10.1080/14725840902808868 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14725840902808868 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Humanisation of the Subject in David Foster Wallace's Fiction

ArsAeterna–Volume6/number1/2014 DOI:10.2478/aaͲ2014Ͳ0005 HumanisationoftheSubjectinDavidFosterWallace’sFiction:From Postmodernism,AvantͲPoptoNewSensicerity?(TriͲStan:ISold SisseeNartoEcko,1999) JaroslavKušnír Jaroslav Kušnír works at the University of Prešov, Prešov, Slovakia. His research focuses mainly on contemporary fiction, Australian literature and postcolonial writing. His publications include the monograph on Richard Brautigan and Donald Barthelme called Poetika americkej postmodernej prózy (2001) and several contributions to Slovak and foreign literary journals. Abstract David Foster Wallace’s fiction is often considered to be an expression of the new American fiction emerging in the late 1980s, the authors of which expressed a certain distance from the dehumanised and linguistically constructed subject of postmodern fiction, and which depicted individuals influenced by mass media, pop culture and technology in technologically advanced American society. David Foster Wallace’s short story Tri-Stan: I Sold Sissee Nar to Ecko (1999), however, was also included in the Avant-Pop Anthology (Larry McCaffery, L., eds. After Yesterday’s Crash: The Avant-Pop Anthology. London, New York: Penguin, 1995). Some other critics (Adam Kelly, for example) consider him to be an author who expresses New Sincerity in his depiction of reality, which is a tendency in fiction trying to depict human experience and emotions through the use of language and which does not emphasise the human subject and experience to be a product of the interplay of signifiers as understood by Deconstruction criticism and many postmodern authors. This paper will analyse David Foster Wallace’s use of narrative strategies that are connected with postmodern narrative techniques and, at the same time, the way they express a distance from them through a depiction of human experience as interactive communication between human subjects. -

AVANT-POP 101. Here's a List of Works That Helped to Shape Avant-Pop Ideology and Aesthetics, Along with Books, Albums, Films, T

Larry McCaffery AVANT-POP 101. Here's a list of works that helped to shape Avant-Pop ideology and aesthetics, along with books, albums, films, television shows, works of criticism, and other cultural artifacts by the Avant-Pop artists themselves, in roughly chronological order. PRECURSORS: The Odyssey (Homer, c. 700 B.C.). Homer's The Odyssey had it all: a memorable, larger-than-life super-hero (Ulysses); a war grand enough that its name alone (Trojan) is still used to sell condoms; descriptions of travels through exotic places; hideous bad-guys (like the Cyclops) and bad gals (Circe); an enduring love affair (Penelope); a happy ending. Commentators have long regarded The Odyssey as Western literature's first epic and masterpiece. What hasn't been noted until now, however, is that its central features—for instance, its blend of high seriousness with popular culture, a self-conscious narrator, magical realism, appropriation, plagiarism, casual blending of historical materials with purely invented ones, foregrounding of its own artifice, reflexivity, the use of montage and jump cuts—also made it the first postmodern, A-P masterpiece, as well. Choju giga (Bishop Toba, 12th century). Choju giga—or the "Animal Scrolls," as Toba's work is known—was a narrative picture scroll that portrayed, among other things, Walt Disney-style anthropomorphized animals engaged in a series of wild (and occasionally wildly erotic) antics that mocked Toba's own calling (the Buddhist clergy); in its surrealist blend of nightmare and revelry, Toba Choju giga can rightly be said to be the origins not only of cartoons but of an avant-pop aesthetics of cartoon forms that successfully serve "serious" purposes of satire, philosophical speculation and social commentary. -

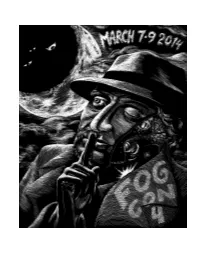

Fogcon 4 Program

Contents Comments from the Chair By Guy W. Thomas 2 Convention Committee 2 Honored Guest Tim Powers By Cliff Winnig 3 Honored Guest Seanan McGuire By Tanya Huff 4 Honored Ghost James Tiptree, Jr. By Jeffrey Smith 5 About Cons – Interviews with some of our guests 6 Everything but the Signature Is Me By James Tiptree, Jr. 10 Hotel 14 Registration 15 Consuite 15 Dealers’ Room 15 Game Room 15 Safety Team 15 Programming, Friday March 7, 2014 17 Programming, Saturday, March 8, 2014 20 Programming, Sunday, March 9, 2014 26 Program Participants 28 Access Information 36 Anti-Harassment Policy 39 Photography Policy 39 FOGcon 4 – Hours and Useful Information Back Cover Editor: Kerry Ellis; Proofreaders: Lynn Alden Kendall, Wendy Shaffer, Guy W. Thomas, Aaron I. Spielman and Debbie Notkin Cover: Art by Eli Bishop; Printed on 30% recycled PCW acid free paper Printed on 100% recycled PCW acid free paper. FOGcon 4 is a project done jointly by Friends of Genre and the Speculative Literature Foundation. Copyright © 2014 FOGcon 4. All Rights Revert to the Authors and Artists. 1 Comments from the Chair By Guy W. Thomas Welcome to FOGcon 4! Once again we bring you the convention by the Bay. FOGcon has always been a convention by and for genre fiction fans. This is our party, our celebration. The theme this year is Secrets. The secret I learned about running conventions from the founder and chair of the first three FOGcons, the radiant and perspicacious Vylar Kaftan is: find cool, talented people who also want to put on a convention and that you like hanging out with anyway. -

The Future of Cyberpunk Criticism: Introduction to Transpacific Cyberpunk

arts Editorial The Future of Cyberpunk Criticism: Introduction to Transpacific Cyberpunk Takayuki Tatsumi Department of English, Keio University, Tokyo 108-8345, Japan; [email protected] Received: 19 March 2019; Accepted: 21 March 2019; Published: 25 March 2019 The genesis of cyberpunk criticism could well be dated to March 1987, when Stephen P. Brown inaugurated the first cyberpunk journal Science Fiction Eye together with his friend Daniel J. Steffan, with Paul DiFilippo, Elizabeth Hand, and myself as contributing editors. Of course, it is the impact of William Gibson’s multiple-award-winning Neuromancer in 1984, featuring the anti-hero Case’s adventures in what Gibson himself called “cyberspace,” that aroused popular interest in the new style of speculative fiction. This surge of interest led Gibson’s friend, writer Bruce Sterling, the editor of the legendary critical fanzine Cheap Truth, to serve as unofficial chairman of the brand-new movement. Thus, on 31 August 1985, the first cyberpunk panel took place at NASFiC (The North American Science Fiction Convention) in Austin, Texas, featuring writers in Sterling’s circle: John Shirley, Lewis Shiner, Pat Cadigan, Greg Bear, and Rudy Rucker. As I was studying American literature at the graduate school of Cornell University during the mid-1980s, I was fortunate enough to witness this historical moment. After the panel, Sterling said, “Our time has come!” Thus, from the spring of 1986, I decided to conduct a series of interviews with cyberpunk writers, part of which are now easily available in Patrick A. Smith’s edited Conversations with William Gibson (University Press of Mississippi 2014).