{PDF EPUB} Pie Traynor a Baseball Biography by James Forr Pie Traynor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kit Young's Sale

KIT YOUNG’S SALE #92 VINTAGE HALL OF FAMERS ROOKIE CARDS SALE – TAKE 10% OFF 1954 Topps #128 Hank Aaron 1959 Topps #338 Sparky 1956 Topps #292 Luis Aparicio 1954 Topps #94 Ernie Banks EX- 1968 Topps #247 Johnny Bench EX o/c $550.00 Anderson EX $30.00 EX-MT $115.00; VG-EX $59.00; MT $1100.00; EX+ $585.00; PSA PSA 6 EX-MT $120.00; EX-MT GD-VG $35.00 5 EX $550.00; VG-EX $395.00; VG $115.00; EX o/c $49.00 $290.00 1909 E90-1 American Caramel 1909 E95 Philadelphia Caramel 1887 Tobin Lithographs Dan 1949 Bowman #84 Roy 1967 Topps #568 Rod Carew NR- Chief Bender PSA 2 GD $325.00 Chief Bender FR $99.00 Brouthers SGC Authentic $295.00 Campanella VG-EX/EX $375.00 MT $320.00; EX-MT $295.00 1958 Topps #343 Orlando Cepeda 1909 E92 Dockman & Sons Frank 1909 E90-1 American Caramel 1910 E93 Standard Caramel 1909 E90-1 American Caramel PSA 5 EX $55.00 Chance SGC 30 GD $395.00 Frank Chance FR-GD $95.00 Eddie Collins GD-VG Sam Crawford GD $150.00 (paper loss back) $175.00 1932 U.S. Caramel #7 Joe Cronin 1933 Goudey #23 Kiki Cuyler 1933 Goudey #19 Bill Dickey 1939 Play Ball #26 Joe DiMaggio 1957 Topps #18 Don Drysdale SGC 50 VG-EX $375.00 GD-VG $49.00 VG $150.00 EX $695.00; PSA 3.5 VG+ $495.00 NR-MT $220.00; PSA 6 EX-MT $210.00; EX-MT $195.00; EX $120.00; VG-EX $95.00 1910 T3 Turkey Red Cabinet #16 1910 E93 Standard Caramel 1909-11 T206 (Polar Bear) 1948 Bowman #5 Bob Feller EX 1972 Topps #79 Carlton Fisk EX Johnny Evers VG $575.00 Johnny Evers FR-GD $99.00 Johnny Evers SGC 45 VG+ $170.00; VG $75.00 $19.95; VG-EX $14.95 $240.00 KIT YOUNG CARDS • 4876 SANTA MONICA AVE, #137 • DEPT. -

RAIDER BASEBALL Shippensburg University Table of Contents Shippensburg About Quick Facts/PSAC

2012 SHIPPENSBURG UNIVERSITY RAIDER BASEBALL WWW.SHIPRAIDERS.COM SHIPPENSBURG UNIVERSITY Table of Contents SHIPPENSBURG About Quick Facts/PSAC ..................... 2 Quick Facts About the University .................. 3 Official Name of University: Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania General Information Academics & Athletics ............... 4 Member: The Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education • Founded in 1871 as the Cumber- Academic Support Services ........ 5 Location and Zip Code: Shippensburg, Pa. 17257 land Valley State Normal School Athletic Administration ............. 6 President: Dr. William N. Ruud • Comprehensive regional public Coaches .................................7-10 Undergraduate Enrollment: 7,200 university Roster ....................................... 11 Overall Enrollment: 8,300 • Member of the Pennsylvania State Season Outlook ...................12-14 Founded: 1871 System of Higher Education • Located on 200 acres in southcen- Colors: Red and Blue Players .................................15-31 tral Pennsylvania 2011 Season Review ............32-33 Nickname: Raiders 2011 Season Results ................. 34 Conference: Pennsylvania State Athletic Enrollment 2011 Statistics .....................35-36 Other Affiliations: NCAA Division II • 7,200 undergraduate students and 2011 PSAC Results .............37-39 Athletic Director: Jeff Michaels 1,100 graduate students • 53% women and 47% men History ................................40-41 Athletic Department Phone: (717) 477-1711 • 37% of students live on campus -

Kit Young's Sale #131

page 1 KIT YOUNG’S SALE #131 1952-55 DORMAND POSTCARDS We are breaking a sharp set of the scarce 1950’s Dormand cards. These are gorgeous full color postcards used as premiums to honor fan autograph requests. These are 3-1/2” x 5-1/2” and feature many of the game’s greats. We have a few of the blank back versions plus other variations. Also, some have been mailed so they usually include a person’s address (or a date) plus the 2 cent stamp. These are marked with an asterisk (*). 109 Allie Reynolds .................................................................................. NR-MT 35.00; EX-MT 25.00 110 Gil McDougald (small signature) ..................................................................... autographed 50.00 110 Gil McDougald (small signature) ..............................................................................NR-MT 50.00 110 Gil McDougald (large signature) ....................................................... NR-MT 30.00; EX-MT 25.00 111 Mickey Mantle (bat on shoulder) ................................................. EX 99.00; GD watermark 49.00 111 Mickey Mantle (batting) ........................................................................................ EX-MT 199.00 111 Mickey Mantle (jumbo 6” x 9” blank back) ..................................................... EX-MT rare 495.00 111 Mickey Mantle (jumbo 6” x 9” postcard back) ................................................ GD-VG rare 229.00 111 Mickey Mantle (super jumbo 9” x 12” postcard back) .......................VG/VG-EX tape back 325.00 112 -

Triple Plays Analysis

A Second Look At The Triple Plays By Chuck Rosciam This analysis updates my original paper published on SABR.org and Retrosheet.org and my Triple Plays sub-website at SABR. The origin of the extensive triple play database1 from which this analysis stems is the SABR Triple Play Project co-chaired by myself and Frank Hamilton with the assistance of dozens of SABR researchers2. Using the original triple play database and updating/validating each play, I used event files and box scores from Retrosheet3 to build a current database containing all of the recorded plays in which three outs were made (1876-2019). In this updated data set 719 triple plays (TP) were identified. [See complete list/table elsewhere on Retrosheet.org under FEATURES and then under NOTEWORTHY EVENTS]. The 719 triple plays covered one-hundred-forty-four seasons. 1890 was the Year of the Triple Play that saw nineteen of them turned. There were none in 1961 and in 1974. On average the number of TP’s is 4.9 per year. The number of TP’s each year were: Total Triple Plays Each Year (all Leagues) Ye a r T P's Ye a r T P's Ye a r T P's Ye a r T P's Ye a r T P's Ye a r T P's <1876 1900 1 1925 7 1950 5 1975 1 2000 5 1876 3 1901 8 1926 9 1951 4 1976 3 2001 2 1877 3 1902 6 1927 9 1952 3 1977 6 2002 6 1878 2 1903 7 1928 2 1953 5 1978 6 2003 2 1879 2 1904 1 1929 11 1954 5 1979 11 2004 3 1880 4 1905 8 1930 7 1955 7 1980 5 2005 1 1881 3 1906 4 1931 8 1956 2 1981 5 2006 5 1882 10 1907 3 1932 3 1957 4 1982 4 2007 4 1883 2 1908 7 1933 2 1958 4 1983 5 2008 2 1884 10 1909 4 1934 5 1959 2 -

National~ Pastime

'II Welcome to baseball's past, as vigor TNP, ous, discordant, and fascinating as that ======.==1 of the nation whose pastime is cele brated in these pages. And to those who were with us for TNP's debut last fall, welcome back. A good many ofyou, we suspect, were introduced to the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) with that issue, inasmuchas the membership of the organization leapt from 1600 when this column was penned last year to 4400 today. Ifyou are not already one of our merry band ofbaseball buffs, we ==========~THE-::::::::::::================== hope you will considerjoining. Details about SABR mem bership and other Society publications are on the inside National ~ Pastime back cover. A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY What's new this time around? New writers, for one (excepting John Holway and Don Nelson, who make triumphant return appearances). Among this year's crop is that most prolific ofauthors, Anon., who hereby goes The Best Fielders of the Century, Bill Deane 2 under the nom de plume of "Dr. Starkey"; his "Ballad of The Day the Reds Lost, George Bulkley 5 Old Bill Williams" is a narrative folk epic meriting com The Hapless Braves of 1935, Don Nelson 10 parison to "Casey at the Bat." No less worthy ofattention Out at Home,jerry Malloy 14 is this year's major article, "Out at Home," an exam Louis Van Zelst in the Age of Magic, ination of how the color line was drawn in baseball in john B. Holway 30 1887, and its painful consequences for the black players Sal Maglie: A Study in Frustration, then active in Organized Baseball. -

Final Round Reached in Handball Play

t. 20 rah OTTAWA JOURNAL THURSDAY. MAY 9. 1940. Vancouver Gagers Win First Game of .Canadian Finals sr Figure Prominently in Swimming Meet Maple Leafs Triumph, 33-26 ; Another Honey Cloud Wins 4th Stake Over Montreal Y.M.H.A. Angle In Rags-to-Riches Showing —By JACK MAUNDER Former Selling Plater Heads Dixie Handicap Deadly Shooting of Western Challengers CAN-AM baseball gets away to- Plays Important Role—Captain Joe Ross Stars day on four fronts with Sen- As Pimlico Prepares for Preokness ators, who are ours when they're not Ogdensburg's, at Oswego. The Hy Lit K MITCHELL. Kossy, tall centre, bagged five on BALTIMORE, Md , May 8.—iW worth and Belair stud's Isolator rest of the opening day program —Honey Cloud, a former selling was making a belated bid. MONTREAL, May 8. — tCP) — three free shots and a basket. includes two first starts. "Knotty" plater that's just as game as horses But they couldn't make Honey Tast-breaking plays. capped by Other Y.M.H.A. scorers were Joe Lee's new Auburn nine is at Rome. come, capped his rags-to-riches Cloud call it quits and he lasted dead:y sniping around the basket, Waxman, with three points and the Oneonta newcomers are at career today with a hard-earned just long enough to stave off his Bernie Ziff and Dickie Ditkofsky gate Vancouver Maple Leafs a Utica. victory in the $20,000 added challengers. Filisteo, second by with two each. Dixie Handicap at Pimlico. a nose, beat out Aethelwold by 33-26 victory over Montreal Y.M. -

Weekly Notes 082417

MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL WEEKLY NOTES THURSDAY, AUGUST 24, 2017 NATIONAL TREASURE With a victory on Sunday at San Diego, Washington Nationals starting pitcher Gio Gonzalez improved to 12-5 on the season with a 2.39 ERA. The 31-year-old left-hander has won each of his last four starts, permitting just one earned run over 27.2 innings pitched (0.33 ERA). According to Elias, the only other pitchers in Expos/Nationals history to post an ERA below 0.50 over four straight starts within one season (all wins), are Charlie Lea (0.28 in 1981), Hall of Famer Pedro Martinez (0.30 in 1997) and Javier Vazquez (0.28 in 2001). With his next start, Gio will attempt to become the fourth pitcher in Montreal/Washington franchise history to pick up a victory while tossing at least 6.0 innings and allowing one earned run or less in fi ve consecutive starts, and just the second to do so in a single season. Jordan Zimmermann accomplished the feat in six consecutive starts in 2012, while Martinez did so in six straight starts across the 1996-97 seasons. Gonzalez’ teammate Joe Ross compiled a streak of fi ve such starts between 2015-16. The two-time All-Star has now pitched into the sixth inning in 19 consecutive starts, and he has lasted at least 5.0 innings in 25 straight outings. Steve Rogers holds the all-time franchise mark of 62 straight starts of at least 5.0 innings pitched from May 22, 1977 - April 15, 1979. -

Estimated Age Effects in Baseball

Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports Volume 4, Issue 1 2008 Article 1 Estimated Age Effects in Baseball Ray C. Fair, Yale University Recommended Citation: Fair, Ray C. (2008) "Estimated Age Effects in Baseball," Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports: Vol. 4: Iss. 1, Article 1. DOI: 10.2202/1559-0410.1074 ©2008 American Statistical Association. All rights reserved. Brought to you by | Yale University Library New Haven (Yale University Library New Haven) Authenticated | 172.16.1.226 Download Date | 3/28/12 11:34 PM Estimated Age Effects in Baseball Ray C. Fair Abstract Age effects in baseball are estimated in this paper using a nonlinear fixed-effects regression. The sample consists of all players who have played 10 or more "full-time" years in the major leagues between 1921 and 2004. Quadratic improvement is assumed up to a peak-performance age, which is estimated, and then quadratic decline after that, where the two quadratics need not be the same. Each player has his own constant term. The results show that aging effects are larger for pitchers than for batters and larger for baseball than for track and field, running, and swimming events and for chess. There is some evidence that decline rates in baseball have decreased slightly in the more recent period, but they are still generally larger than those for the other events. There are 18 batters out of the sample of 441 whose performances in the second half of their careers noticeably exceed what the model predicts they should have been. All but 3 of these players played from 1990 on. -

Lewis R. Dorman, IV. Ghosts of Glory: a Bibliographic Essay Concerning Pre- 1941 Baseball Autobiography and Oral History

Lewis R. Dorman, IV. Ghosts of Glory: a Bibliographic Essay Concerning Pre- 1941 Baseball Autobiography and Oral History. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S degree. April 2005. 93 pages. Advisor: Jerry Saye. This paper documents published sources related to autobiographies and oral histories of baseball players, pitchers, and managers who performed the preponderance of their professional career before the United States of America’s involvement with the Second World War. The paper separates the individual autobiographies into three sections based upon the era in which the player is most associated with: the Iron Age (1869-1902), the Silver Age (1903-1922), and the Golden Age (1904-1941). Each section arranges the players alphabetically by surname, and every player entry contains a photograph, brief biographical information, a quotation from the autobiography, and lists of anecdotal works, biographies, films, and museums correlating to the player, when available. The fourth section of the paper concerns oral history (1869-1941), arranging the monographs alphabetically, with each entry including information about the players interviewed similar to the first three sections, but arranged by the player’s occurrence in the monograph. Headings: Baseball players -- United States -- Autobiography Baseball -- United States -- Bibliography Baseball -- United States -- History Baseball -- United States -- Oral history GHOSTS OF GLORY: A BIBLIOGRAPHIC ESSAY CONCERNING PRE-1941 BASEBALL AUTOBIOGRAPHY AND ORAL HISTORY by Lewis R. Dorman, IV A Master's paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. -

The Ithacan, 1949-02-25

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 1948-49 The thI acan: 1940/41 to 1949/50 2-25-1949 The thI acan, 1949-02-25 Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1948-49 Recommended Citation Ithaca College, "The thI acan, 1949-02-25" (1949). The Ithacan, 1948-49. 10. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1948-49/10 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 1940/41 to 1949/50 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 1948-49 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Cinderella Ball "John Loves Mary" Eagles' Ballroom Hilarious Modern Comedy Saturday 9 to 1 College Theater $2.00 per Couple Mar. 2, 3, 4, 5 - 8:15 P.M. Sponsored by Kappa Gamma Psi Until Student Admission $.40 Vol. 20, No. IO Ithaca College, Ithaca, New York, February 25, 1949 Page 1 Music Department Announces Dr. Haines Addresses Girls Ithaca College-Varsity Club Clinic Success; Programs For Forthcoming Concerts At WCC Mass Meeting Baseball Big-leaguers Entertain Capacity Audiences An all-college assoc1at1on of by Bob Wendland Onhesfra Feature women students, meeting once a Faculty String Quartet lo month for discussion of topics of Approximately four hundred students, coaches, and baseball fans In Theater March 6 Soloists March 9 general interest, was suggested by atte~ded the afternoon an? ~veni~g sessions of the first Ithaca College Dr. Charles Haines, IC vice presi Varsity Club Baseball Chmc which was held February 15 in Foster The Ithaca College Faculty String On Wednesday evening, \larch 9, dent, at a mass meeting of women Hall. -

The Ithacan, 1950-02-10

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 1949-50 The thI acan: 1940/41 to 1949/50 2-10-1950 The thI acan, 1950-02-10 Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1949-50 Recommended Citation Ithaca College, "The thI acan, 1950-02-10" (1950). The Ithacan, 1949-50. 8. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1949-50/8 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 1940/41 to 1949/50 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 1949-50 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Scampers Dance Tomorrow Tune in Sunday 4:30 WHCU Seneca Gym 10-1 A.M. OF ONE BLOOD Free Admission Until Radio Workshop Production ; Vol. 21, No. 8 Ithaca College, Ithaca, New York, February 10, 1950 Page 1 ;Concert: and Recital Junior Weekend Scheduled For May; 1 Highlight: Coming Week Student Council Plans Float Parade Beethoven Program Featured Wed. Original Transcriptions Committees Chosen To ·- -- - --· - And Narration Programmed Carry Out Program ,-- Through the thick haze of exams Highlighting the band concert to I be presented by the Ithaca College ·- and Scampers, the Junior Class ·~~l,,;illJk.,: Officers led by Ev Rouse have I Concert Band on Sunday evening, February 12, will be four original managed to set the plans for their 1· transcriptions for band made by class activities this Spring. The ma I Professor Walter Beeler, the band's jor project each year is the Junior conductor, and bv Tames Truscello weekend and this year Mr. -

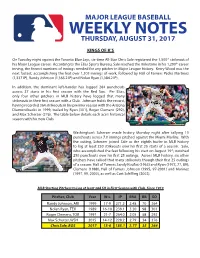

Weekly Notes 083117

MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL WEEKLY NOTES THURSDAY, AUGUST 31, 2017 KINGS OF K’S On Tuesday night against the Toronto Blue Jays, six-time All-Star Chris Sale registered the 1,500th strikeout of his Major League career. According to the Elias Sports Bureau, Sale reached the milestone in his 1,290th career inning, the fewest numbers of innings needed for any pitcher in Major League history. Kerry Wood was the next fastest, accomplishing the feat over 1,303 innings of work, followed by Hall of Famers Pedro Martinez (1,337 IP), Randy Johnson (1,365.2 IP) and Nolan Ryan (1,384.2 IP). In addition, the dominant left-hander has logged 264 punchouts across 27 starts in his fi rst season with the Red Sox. Per Elias, only four other pitchers in MLB history have logged that many strikeouts in their fi rst season with a Club. Johnson holds the record, having recorded 364 strikeouts in his premier season with the Arizona Diamondbacks in 1999, trailed by Ryan (301), Roger Clemens (292), and Max Scherzer (276). The table below details each ace’s historical season with his new Club. Washington’s Scherzer made history Monday night after tallying 10 punchouts across 7.0 innings pitched against the Miami Marlins. With the outing, Scherzer joined Sale as the eighth hurler in MLB history to log at least 230 strikeouts over his fi rst 25 starts of a season. Sale, who accomplished the feat following his start on August 19th, notched 250 punchouts over his fi rst 25 outings. Across MLB history, six other pitchers have tallied that many strikeouts though their fi rst 25 outings of a season: Hall of Famers Sandy Koufax (1965) and Ryan (1973, 77, 89); Clemens (1988), Hall of Famers Johnson (1995, 97-2001) and Marinez (1997, 99, 2000), as well as Curt Schilling (2002).