Cameron Tait P Post

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics 2017

DIGEST OF UNITED KINGDOM ENERGY STATISTICS 2017 July 2017 This document is available in large print, audio and braille on request. Please email [email protected] with the version you require. Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics Enquiries about statistics in this publication should be made to the contact named at the end of the relevant chapter. Brief extracts from this publication may be reproduced provided that the source is fully acknowledged. General enquiries about the publication, and proposals for reproduction of larger extracts, should be addressed to BEIS, at the address given in paragraph XXVIII of the Introduction. The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) reserves the right to revise or discontinue the text or any table contained in this Digest without prior notice This is a National Statistics publication The United Kingdom Statistics Authority has designated these statistics as National Statistics, in accordance with the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 and signifying compliance with the UK Statistics Authority: Code of Practice for Official Statistics. Designation can be broadly interpreted to mean that the statistics: ñ meet identified user needs ONCEñ are well explained and STATISTICSreadily accessible HAVE ñ are produced according to sound methods, and BEENñ are managed impartially DESIGNATEDand objectively in the public interest AS Once statistics have been designated as National Statistics it is a statutory NATIONALrequirement that the Code of Practice S TATISTICSshall continue to be observed IT IS © A Crown copyright 2017 STATUTORY You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. -

Reunification in South Wales

Power Wind Marine Delivering marine expertise worldwide www.metoc.co.uk re News Part of the Petrofac group www.tnei.co.uk RENEWABLE ENERGY NEWS • ISSUE 226 27 OCTOBER 2011 TAG on for Teesside spoils TAG Energy Solutions is in negotiations for a contract to fabricate and deliver a “significant” proportion of Reunification monopiles for the Teesside offshore wind farm. PAGE 2 Middlemoor winning hand in south Wales Vestas is in pole position to land a plum supply RWE npower renewables with Nordex for 14 N90 middle when two contract at one of the largest remaining onshore has thrown in the towel 2.5MW units and has landowners decided in wind farms in England, RWE npower renewables’ at an 11-turbine wind roped Powersystems UK 2005 to proceed instead 18-turbine Middlemoor project in Northumberland. farm in south Wales and to oversee electrical with Pennant. offloaded the asset to works. Parent company Years of wrangling PAGE 3 local developer Pennant Walters Group will take ensued between Walters. care of civil engineering. environmental regulators Huhne hits the high notes The utility sold the The 35MW project is due and planners in Bridgend Energy secretary Chris Huhne took aim at “faultfinders consented four-turbine online by early 2013. and Rhondda Cynon Taf and curmudgeons who hold forth on the impossibility portion of its Fforch Nest The reunification of who were keen to see of renewables” in a strongly worded keynote address project in Bridgend and Fforch Nest and Pant-y- the projects rationalised to RenewableUK 2011 in Manchester this week. is in line to divest the Wal brings to an end a using a shared access remaining seven units if decade-long struggle and grid connection. -

WIND ENERGY PROJECT FINANCING ONSHORE CASE STUDY with Zephir Lidar

WIND ENERGY PROJECT FINANCING ONSHORE CASE STUDY with ZephIR Lidar “ZephIR delivers bankable, finance-grade wind data to Banks taking sites forward in a timely, cost effective and safe manner - correlations with a short mast are far better than often found when comparing two cup anemometers.” - REG Windpower world-leading lidar innovation finance-grade, ‘bankable’ wind data sets unparalleled data availability at all heights accurate, proven measurements in all terrains 650+ deployments and 3 million hours operation zephirlidar.com REG WINDPOWER LTD. Established in 1989 as Cornwall Light & Power, REG Windpower develops, builds and owns wind farms. The company now operate eleven wind farms (with a further two in construction) in England & Wales with an additional 900MW+ in development across the UK. In 2009, REG performed a strategic review of their approach to wind monitoring and the question was raised how to monitor wind more rapidly and more cost effectively against anemometry with traditional tall met masts. Zephir + short MAST MethodoLOGY REG implemented a strategy for 16 metre short met masts In 2009, REG purchased three ZephIRs to operate across the coupled with 6 month ZephIR lidar deployments for the rapid company’s entire portfolio of projects. The methodology is to and cost effective measurement of wind quality on potential install the short mast as the long term reference, collecting sites, for the following reasons: at least 12 months data covering seasonal variation. The ZephIR is installed for 6 months next to the mast - 6 months 1. Short masts are easier to get planning permission to is an adequate length of time to measure a significant range install on site - taller masts can take much longer. -

Local Energy

House of Commons Energy and Climate Change Committee Local Energy Sixth Report of Session 2013–14 Volume II Additional written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be published 9 May and 16 July 2013 Published on 6 August 2013 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited The Energy and Climate Change Committee The Energy and Climate Change Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department of Energy and Climate Change and associated public bodies. Current membership Mr Tim Yeo MP (Conservative, South Suffolk) (Chair) Dan Byles MP (Conservative, North Warwickshire) Barry Gardiner MP (Labour, Brent North) Ian Lavery MP (Labour, Wansbeck) Dr Phillip Lee MP (Conservative, Bracknell) Rt Hon Peter Lilley MP (Conservative, Hitchin & Harpenden) Albert Owen MP (Labour, Ynys Môn) Christopher Pincher MP (Conservative, Tamworth) John Robertson MP (Labour, Glasgow North West) Sir Robert Smith MP (Liberal Democrat, West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine) Dr Alan Whitehead MP (Labour, Southampton Test) The following members were also members of the committee during the Parliament: Gemma Doyle MP (Labour/Co-operative, West Dunbartonshire) Tom Greatrex MP (Labour, Rutherglen and Hamilton West) Laura Sandys MP (Conservative, South Thanet) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the internet at www.parliament.uk/parliament.uk/ecc. -

Spotlight on Northern Ireland Regional Focus

COMMUNICATION HUB FOR THE WIND ENERGY INDUSTRY ‘TITANIC’ SPOTLIGHT ON NORTHERN IRELAND REGIONAL FOCUS GLOBAL WIND ALLIANCE COMPETEncY BasED TRaininG FEBRUARY/MARCH 2012 | £5.25 www.windenergynetwork.co.uk INTRODUCTION COMMUNICATING YOUR THOUGHTS AND OPINIONS WIND ENERGY NETWORK TV CHANNEL AND ONLINE LIBRARY These invaluable industry resources continue to build and we are very YOU WILL FIND WITHIN THIS We hope you enjoy the content and pleased with the interest and support EDITION CONTRIBUTIONS WHICH please feel free to contact us to make of our proposed sponsors. Please give COULD BE DESCRIBED AS OPINION your feelings known – it’s good to talk. the team a call and find out how to get PIECES. THEY ARE THERE TO FOCUS involved in both. ATTENTION ON VERY IMPORTANT ‘SpoTLIGHT ON’ regIONAL FOCUS SUBJECT AREAS WITH A VIEW Our regional focus in this edition features Remember they are free to TO GALVANISING OPINION AND Northern Ireland. Your editor visited contribute and free to access. BRINGING THE INDUSTRY TOGETHER the area in late November 2011 when TO ENSURE EFFECTIVE PROGRESS reporting on the Quo Vadis conference Please also feel free to contact us AND THEREFORE SUCCESS. and spent a very enjoyable week soaking if you wish to highlight any specific up the atmosphere, local beverages as area within the industry and we will Ray Sams from Spencer Coatings well the Irish hospitality (the craic). endeavour to encourage debate and features corrosion in marine steel feature the issue within our publication. structures, Warren Fothergill from As you will see it is a very substantial Group Safety Services on safety feature and the overall theme is one of passports and Michael Wilder from excitement and forward thinking which Petans on competency based training will ensure Northern Ireland is at the standardisation. -

International Smallcap Separate Account As of July 31, 2017

International SmallCap Separate Account As of July 31, 2017 SCHEDULE OF INVESTMENTS MARKET % OF SECURITY SHARES VALUE ASSETS AUSTRALIA INVESTA OFFICE FUND 2,473,742 $ 8,969,266 0.47% DOWNER EDI LTD 1,537,965 $ 7,812,219 0.41% ALUMINA LTD 4,980,762 $ 7,549,549 0.39% BLUESCOPE STEEL LTD 677,708 $ 7,124,620 0.37% SEVEN GROUP HOLDINGS LTD 681,258 $ 6,506,423 0.34% NORTHERN STAR RESOURCES LTD 995,867 $ 3,520,779 0.18% DOWNER EDI LTD 119,088 $ 604,917 0.03% TABCORP HOLDINGS LTD 162,980 $ 543,462 0.03% CENTAMIN EGYPT LTD 240,680 $ 527,481 0.03% ORORA LTD 234,345 $ 516,380 0.03% ANSELL LTD 28,800 $ 504,978 0.03% ILUKA RESOURCES LTD 67,000 $ 482,693 0.03% NIB HOLDINGS LTD 99,941 $ 458,176 0.02% JB HI-FI LTD 21,914 $ 454,940 0.02% SPARK INFRASTRUCTURE GROUP 214,049 $ 427,642 0.02% SIMS METAL MANAGEMENT LTD 33,123 $ 410,590 0.02% DULUXGROUP LTD 77,229 $ 406,376 0.02% PRIMARY HEALTH CARE LTD 148,843 $ 402,474 0.02% METCASH LTD 191,136 $ 399,917 0.02% IOOF HOLDINGS LTD 48,732 $ 390,666 0.02% OZ MINERALS LTD 57,242 $ 381,763 0.02% WORLEYPARSON LTD 39,819 $ 375,028 0.02% LINK ADMINISTRATION HOLDINGS 60,870 $ 374,480 0.02% CARSALES.COM AU LTD 37,481 $ 369,611 0.02% ADELAIDE BRIGHTON LTD 80,460 $ 361,322 0.02% IRESS LIMITED 33,454 $ 344,683 0.02% QUBE HOLDINGS LTD 152,619 $ 323,777 0.02% GRAINCORP LTD 45,577 $ 317,565 0.02% Not FDIC or NCUA Insured PQ 1041 May Lose Value, Not a Deposit, No Bank or Credit Union Guarantee 07-17 Not Insured by any Federal Government Agency Informational data only. -

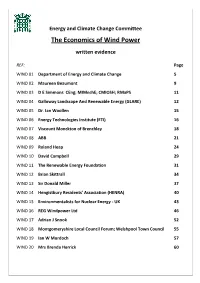

Memorandum Submitted by the Department of Energy and Climate Change (WIND 01)

Energy and Climate Change Committee The Economics of Wind Power written evidence REF: Page WIND 01 Department of Energy and Climate Change 5 WIND 02 Maureen Beaumont 9 WIND 03 D E Simmons CEng; MIMechE; CMIOSH; RMaPS 11 WIND 04 Galloway Landscape And Renewable Energy (GLARE) 12 WIND 05 Dr. Ian Woollen 15 WIND 06 Energy Technologies Institute (ETI) 16 WIND 07 Viscount Monckton of Brenchley 18 WIND 08 ABB 21 WIND 09 Roland Heap 24 WIND 10 David Campbell 29 WIND 11 The Renewable Energy Foundation 31 WIND 12 Brian Skittrall 34 WIND 13 Sir Donald Miller 37 WIND 14 Hengistbury Residents' Association (HENRA) 40 WIND 15 Environmentalists for Nuclear Energy ‐ UK 43 WIND 16 REG Windpower Ltd 46 WIND 17 Adrian J Snook 52 WIND 18 Montgomeryshire Local Council Forum; Welshpool Town Council 55 WIND 19 Ian W Murdoch 57 WIND 20 Mrs Brenda Herrick 60 WIND 21 Mr N W Woolmington 62 WIND 22 Professor Jack W Ponton FREng 63 WIND 23 Mrs Anne Rogers 65 WIND 24 Global Warming Policy Foundation (GWPF) 67 WIND 25 Derek Partington 70 WIND 26 Professor Michael Jefferson 76 WIND 27 Robert Beith CEng FIMechE, FIMarE, FEI and Michael Knowles CEng 78 WIND 28 Barry Smith FCCA 81 WIND 29 The Wildlife Trusts (TWT) 83 WIND 30 Wyck Gerson Lohman 87 WIND 31 Brett Kibble 90 WIND 32 W P Rees BSc. CEng MIET 92 WIND 33 Chartered Institution of Water and Environmental Management 95 WIND 34 Councillor Ann Cowan 98 WIND 35 Ian M Thompson 99 WIND 36 E.ON UK plc 102 WIND 37 Brian D Crosby 105 WIND 38 Peter Ashcroft 106 WIND 39 Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE) 109 WIND 40 Scottish Renewables 110 WIND 41 Greenpeace UK; World Wildlife Fund; Friends of the Earth 114 WIND 42 Wales and Borders Alliance 119 WIND 43 National Opposition to Windfarms 121 WIND 44 David Milborrow 124 WIND 45 SSE 126 WIND 46 Dr Howard Ferguson 129 WIND 47 Grantham Research Institute 132 WIND 48 George F Wood 135 WIND 49 Greenersky. -

Renewable Energy and Sustainable Construction Study

Centre for Sustainable Energy Teignbridge District Council Renewable Energy and Sustainable Construction Study Final Report, 7 December 2010 (Amended version) Document revision 1.1 3 St Peter’s Court www.cse.org.uk We are a national charity that shares Bedminster Parade 0117 934 1400 our knowledge and experience to Bristol [email protected] help people change the way they BS3 4AQ reg charity 298740 think and act on energy. Teignbridge Renewable Energy and Sustainable Construction Study Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 5 1) INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 5 2) SUSTAINABLE ENERGY RESOURCES IN TEIGNBRIDGE ...................................................................... 5 3) POTENTIAL FOR DISTRICT HEATING ................................................................................................. 6 4) ENERGY OPPORTUNITIES PLANS .................................................................................................... 7 5) COST OF ZERO CARBON DEVELOPMENT .......................................................................................... 8 6) POLICY IMPLEMENTATION .............................................................................................................. 9 7) CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ....................................................................................... -

Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics 2020

DIGEST OF UNITED KINGDOM ENERGY STATISTICS 2020 This publication is available from: www.gov.uk/government/collections/digest-of-uk-energy- statistics-dukes If you need a version of this document in a more accessible format, please email [email protected]. Please tell us what format you need. It will help us if you say what assistive technology you use. This is a National Statistics publication The United Kingdom Statistics Authority has designated these statistics as National Statistics, in accordance with the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 and signifying compliance with the UK Statistics Authority: Code of Practice for Statistics. The continued designation of these statistics as National Statistics was confirmed in September 2018 following a compliance check by the Office for Statistics Regulation. The statistics last underwent a full assessment against the Code of Practice in June 2014. Designation can be broadly interpreted to mean that the statistics: • meet identified user needs • are well explained and readily accessible • are produced according to sound methods, and • are managed impartially and objectively in the public interest Once statistics have been designated as National Statistics it is a statutory requirement that the Code of Practice shall continue to be observed. © Crown copyright 2020 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third-party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. -

Siemens Annual Report 2015

2015 Geschäftsbericht Annual Report 2015 siemens.com Table of contents . A B C Combined Management Report Consolidated Financial Statements Additional Information A.1 p 2 B.1 p 58 C.1 p 122 Business and economic environment Consolidated Statements Responsibility Statement of Income A.2 p 8 C.2 p 123 Financial performance system B.2 p 59 Independent Auditor ʼs Report Consolidated Statements A.3 p 10 of Comprehensive Income C.3 p 125 Results of operations Report of the Supervisory Board B.3 p 60 A.4 p 15 Consolidated Statements C.4 p 128 Net assets position of Financial Position Corporate Governance B.4 p 61 A.5 p 16 C.5 p 136 Financial position Consolidated Statements Notes and forward- looking of Cash Flows statements A.6 p 20 B.5 p 62 Overall assessment of the economic position Consolidated Statements of Changes in Equity A.7 p 21 B.6 p 64 Subsequent events Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements A.8 p 22 Report on expected developments and associated material opportunities and risks A.9 p 35 Siemens AG A.10 p 38 Compensation Report A.11 p 53 Takeover-relevant information A. Combined Management Report A.1 Business and economic environment A.1.1 The Siemens Group With Dresser- Rand on board, we have a comprehensive port- folio of equipment and capability for the oil and gas industry A.1.1.1 ORGANIZATION AND BASIS OF PRESENTATION and a much expanded installed base, allowing us to address We are a technology company with core activities in the fields the needs of the market with products, solutions and services. -

An Introductory Guide for Housebuilders

Zero carbon homes – an introductory guide for housebuilders Zero carbon homes – an introductory guide for housebuilders February 2009 NHBC Foundation Buildmark House Chiltern Avenue Amersham Bucks HP6 5AP Tel: 01494 735394 Fax: 01494 735365 Email: [email protected] Web: www.nhbcfoundation.org Acknowledgements Photographs courtesy of: Barratt Green House Page 1 BedZED Page 11 Hockerton Housing Project Page 7 Stewart Milne Sigma House Pages 1 and 9 © NHBC Foundation NF14 Published by IHS BRE Press on behalf of the NHBC Foundation February 2009 ISBN 978-1-84806-074-6 FOREWORD Tackling climate change is now widely acknowledged as one of the highest priorities for our society. The homes we live in are responsible for 27% of the UK’s CO2 emissions, and so it is right that attention should focus on how new homes can be designed and constructed to minimise emissions. Since the launch of the first government consultation on zero carbon housing at the end of 2006 I have seen a variety of encouraging initiatives such as the construction of the Barratt Green House on BRE’s Innovation Park in Watford. Builders large and small are increasingly engaging with the challenge of building to world-leading environmental standards. But if we are to implement successfully the zero carbon standard across all new homes built in the UK it is imperative that we have a definition which is realistic, practical and sufficiently flexible to be achievable on all kinds of developments, with all kinds of homes. The government consultation, Definition of zero carbon homes and non-domestic buildings, issued on 17 December 20081 marks a critical stage in our transition towards zero carbon. -

Community Consultation

Core Strategy and Development Management Policies Statement of Consultation - Submission October 2012 2 Contents The consultation and involvement process Page 5 Annex 1: Consolidated list of representors 8 Annex 2: Regulation 20 (pre-submission publication) 11 Representations made under Regulation 20 25 (publication consultation, May/July 2012) Annex 4: Regulation 18 (‘Preferred Options’) stage 139 Annex 5: Regulation 18 (‘Issues and Options’) stage 214 Annex 6: Statement of Community Involvement (summary) 235 3 4 The consultation and involvement process The Statement of Community Involvement This was adopted in January 2008, and revised in September of that year to incorporate procedural changes brought in by the 2008 Planning Act. Although the 2008 Act did away with the ‘Issues and Options’ and ‘Preferred Options’ terminology, the former stage had already been set in motion, and it has been considered logical to present the subsequent (2010) consultation as a ‘preferred option’. The SCI sets out a range of consultation and involvement possibilities. In jkeeping with a strategic document, consultation, especially in the later stages, has focused on the methods which the SCI sets out as standard (advertisement of published documents, use of the Council’s web site, and local mass media), along with targeted locality-based meetings – either to invited stakeholder audiences or public ‘drop in’ sessions. The SCI is available on the ldf section of the Council’s web site www.copeland.gov.uk/ldf, and its Executive Summary is at Annex 7 (page ). Early engagement ‘Stakeholder Launch’ events were held in November 2008, one for stakeholders in the Borough and another for external invitees.